Irrationality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music Notation As a MEI Feasibility Test

Music Notation as a MEI Feasibility Test Baron Schwartz University of Virginia 268 Colonnades Drive, #2 Charlottesville, Virginia 22903 USA [email protected] Abstract something more general than either notation or performance, but does not leave important domains, such as notation, up to This project demonstrated that enough information the implementer. The MEI format’s design also allows a pro- can be retrieved from MEI, an XML format for mu- cessing application to ignore information it does not need and sical information representation, to transform it into extract the information of interest. For example, the format in- music notation with good fidelity. The process in- cludes information about page layout, but a program for musical volved writing an XSLT script to transform files into analysis can simply ignore it. Mup, an intermediate format, then processing the Generating printed music notation is a revealing test of MEI’s Mup into PostScript, the de facto page description capabilities because notation requires more information about language for high-quality printing. The results show the music than do other domains. Successfully creating notation that the MEI format represents musical information also confirms that the XML represents the information that one such that it may be retrieved simply, with good recall expects it to represent. Because there is a relationship between and precision. the information encoded in both the MEI and Mup files and the printed notation, the notation serves as a good indication that the XML really does represent the same music as the notation. 1 Introduction Most uses of musical information require storage and retrieval, 2 Methods usually in files. -

Automated Analysis and Transcription of Rhythm Data and Their Use for Composition

Automated Analysis and Transcription of Rhythm Data and their Use for Composition submitted by Georg Boenn for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Bath Department of Computer Science February 2011 COPYRIGHT Attention is drawn to the fact that copyright of this thesis rests with its author. This copy of the thesis has been supplied on the condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author. This thesis may not be consulted, photocopied or lent to other libraries without the permission of the author for 3 years from the date of acceptance of the thesis. Signature of Author . .................................. Georg Boenn To Daiva, the love of my life. 1 Contents 1 Introduction 17 1.1 Musical Time and the Problem of Musical Form . 17 1.2 Context of Research and Research Questions . 18 1.3 Previous Publications . 24 1.4 Contributions..................................... 25 1.5 Outline of the Thesis . 27 2 Background and Related Work 28 2.1 Introduction...................................... 28 2.2 Representations of Musical Rhythm . 29 2.2.1 Notation of Rhythm and Metre . 29 2.2.2 The Piano-Roll Notation . 33 2.2.3 Necklace Notation of Rhythm and Metre . 34 2.2.4 Adjacent Interval Spectrum . 36 2.3 Onset Detection . 36 2.3.1 ManualTapping ............................... 36 The times Opcode in Csound . 38 2.3.2 MIDI ..................................... 38 MIDIFiles .................................. 38 MIDIinReal-Time.............................. 40 2.3.3 Onset Data extracted from Audio Signals . 40 2.3.4 Is it sufficient just to know about the onset times? . 41 2.4 Temporal Perception . -

TIME SIGNATURES, TEMPO, BEAT and GORDONIAN SYLLABLES EXPLAINED

TIME SIGNATURES, TEMPO, BEAT and GORDONIAN SYLLABLES EXPLAINED TIME SIGNATURES Time Signatures are represented by a fraction. The top number tells the performer how many beats in each measure. This number can be any number from 1 to infinity. However, time signatures, for us, will rarely have a top number larger than 7. The bottom number can only be the numbers 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, et c. These numbers represent the note values of a whole note, half note, quarter note, eighth note, sixteenth note, thirty- second note, sixty-fourth note, one hundred twenty-eighth note, two hundred fifty-sixth note, five hundred twelfth note, et c. However, time signatures, for us, will only have a bottom numbers 2, 4, 8, 16, and possibly 32. Examples of Time Signatures: TEMPO Tempo is the speed at which the beats happen. The tempo can remain steady from the first beat to the last beat of a piece of music or it can speed up or slow down within a section, a phrase, or a measure of music. Performers need to watch the conductor for any changes in the tempo. Tempo is the Italian word for “time.” Below are terms that refer to the tempo and metronome settings for each term. BPM is short for Beats Per Minute. This number is what one would set the metronome. Please note that these numbers are generalities and should never be considered as strict ranges. Time Signatures, music genres, instrumentations, and a host of other considerations may make a tempo of Grave a little faster or slower than as listed below. -

Silent Music

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity Philosophy Faculty Research Philosophy Department Fall 2010 Silent Music Andrew Kania Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/phil_faculty Part of the Philosophy Commons Repository Citation Kania, A. (2010). Silent music. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 68(4), 343-353. doi:10.1111/ j.1540-6245.2010.01429.x This Post-Print is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Silent Music Andrew Kania [This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: Andrew Kania, “Silent Music” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 68 (2010): 343-53, which has been published in final form at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1540- 6245.2010.01429.x/abstract. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance with Wiley Terms and Conditions for Self-Archiving. Please cite only the published version.] Abstract In this essay, I investigate musical silence. I first discuss how to integrate the concept of silence into a general theory or definition of music. I then consider the possibility of an entirely silent musical piece. I begin with John Cage’s 4′33″, since it is the most notorious candidate for a silent piece of music, even though it is not, in fact, silent. I conclude that it is not music either, but I argue that it is a piece of non-musical sound art, rather than simply a piece of theatre, as Stephen Davies has argued. -

Interpreting Tempo and Rubato in Chopin's Music

Interpreting tempo and rubato in Chopin’s music: A matter of tradition or individual style? Li-San Ting A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales School of the Arts and Media Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences June 2013 ABSTRACT The main goal of this thesis is to gain a greater understanding of Chopin performance and interpretation, particularly in relation to tempo and rubato. This thesis is a comparative study between pianists who are associated with the Chopin tradition, primarily the Polish pianists of the early twentieth century, along with French pianists who are connected to Chopin via pedagogical lineage, and several modern pianists playing on period instruments. Through a detailed analysis of tempo and rubato in selected recordings, this thesis will explore the notions of tradition and individuality in Chopin playing, based on principles of pianism and pedagogy that emerge in Chopin’s writings, his composition, and his students’ accounts. Many pianists and teachers assume that a tradition in playing Chopin exists but the basis for this notion is often not made clear. Certain pianists are considered part of the Chopin tradition because of their indirect pedagogical connection to Chopin. I will investigate claims about tradition in Chopin playing in relation to tempo and rubato and highlight similarities and differences in the playing of pianists of the same or different nationality, pedagogical line or era. I will reveal how the literature on Chopin’s principles regarding tempo and rubato relates to any common or unique traits found in selected recordings. -

Chapter 1 "The Elements of Rhythm: Sound, Symbol, and Time"

This is “The Elements of Rhythm: Sound, Symbol, and Time”, chapter 1 from the book Music Theory (index.html) (v. 1.0). This book is licensed under a Creative Commons by-nc-sa 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/ 3.0/) license. See the license for more details, but that basically means you can share this book as long as you credit the author (but see below), don't make money from it, and do make it available to everyone else under the same terms. This content was accessible as of December 29, 2012, and it was downloaded then by Andy Schmitz (http://lardbucket.org) in an effort to preserve the availability of this book. Normally, the author and publisher would be credited here. However, the publisher has asked for the customary Creative Commons attribution to the original publisher, authors, title, and book URI to be removed. Additionally, per the publisher's request, their name has been removed in some passages. More information is available on this project's attribution page (http://2012books.lardbucket.org/attribution.html?utm_source=header). For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page (http://2012books.lardbucket.org/). You can browse or download additional books there. i Chapter 1 The Elements of Rhythm: Sound, Symbol, and Time Introduction The first musical stimulus anyone reacts to is rhythm. Initially, we perceive how music is organized in time, and how musical elements are organized rhythmically in relation to each other. Early Western music, centering upon the chant traditions for liturgical use, was arhythmic to a great extent: the flow of the Latin text was the principal determinant as to how the melody progressed through time. -

Music Braille Code, 2015

MUSIC BRAILLE CODE, 2015 Developed Under the Sponsorship of the BRAILLE AUTHORITY OF NORTH AMERICA Published by The Braille Authority of North America ©2016 by the Braille Authority of North America All rights reserved. This material may be duplicated but not altered or sold. ISBN: 978-0-9859473-6-1 (Print) ISBN: 978-0-9859473-7-8 (Braille) Printed by the American Printing House for the Blind. Copies may be purchased from: American Printing House for the Blind 1839 Frankfort Avenue Louisville, Kentucky 40206-3148 502-895-2405 • 800-223-1839 www.aph.org [email protected] Catalog Number: 7-09651-01 The mission and purpose of The Braille Authority of North America are to assure literacy for tactile readers through the standardization of braille and/or tactile graphics. BANA promotes and facilitates the use, teaching, and production of braille. It publishes rules, interprets, and renders opinions pertaining to braille in all existing codes. It deals with codes now in existence or to be developed in the future, in collaboration with other countries using English braille. In exercising its function and authority, BANA considers the effects of its decisions on other existing braille codes and formats, the ease of production by various methods, and acceptability to readers. For more information and resources, visit www.brailleauthority.org. ii BANA Music Technical Committee, 2015 Lawrence R. Smith, Chairman Karin Auckenthaler Gilbert Busch Karen Gearreald Dan Geminder Beverly McKenney Harvey Miller Tom Ridgeway Other Contributors Christina Davidson, BANA Music Technical Committee Consultant Richard Taesch, BANA Music Technical Committee Consultant Roger Firman, International Consultant Ruth Rozen, BANA Board Liaison iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .............................................................. -

UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Fleeing Franco’s Spain: Carlos Surinach and Leonardo Balada in the United States (1950–75) Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5rk9m7wb Author Wahl, Robert Publication Date 2016 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Fleeing Franco’s Spain: Carlos Surinach and Leonardo Balada in the United States (1950–75) A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Robert J. Wahl August 2016 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Walter A. Clark, Chairperson Dr. Byron Adams Dr. Leonora Saavedra Copyright by Robert J. Wahl 2016 The Dissertation of Robert J. Wahl is approved: __________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements I would like to thank the music faculty at the University of California, Riverside, for sharing their expertise in Ibero-American and twentieth-century music with me throughout my studies and the dissertation writing process. I am particularly grateful for Byron Adams and Leonora Saavedra generously giving their time and insight to help me contextualize my work within the broader landscape of twentieth-century music. I would also like to thank Walter Clark, my advisor and dissertation chair, whose encouragement, breadth of knowledge, and attention to detail helped to shape this dissertation into what it is. He is a true role model. This dissertation would not have been possible without the generous financial support of several sources. The Manolito Pinazo Memorial Award helped to fund my archival research in New York and Pittsburgh, and the Maxwell H. -

Feathered Beams in Cross-Staff Notation 3 Luke Dahn Step 1: on the Bottom Staff, Insert One 32Nd Rest; Trying to Fix This

® Feathered Beams in Cross-Staff Notation 3 Luke Dahn Step 1: On the bottom staff, insert one 32nd rest; Trying to fix this. then enter notes 2 through 8 as a tuplet: seven quarter notes in the space of seven 32nds. (Hide number œ and bracket on tuplet.) 4 #œ #œ œ & 4 Œ Ó œ 4 œ #œ œ œ & 4 bœ œ #œ Œ Ó ®bœ œ #œ Œ Ó Step 3: On the other staff (top here), insert the first note Step 2: Apply cross-staff and stem direction change to following by any random on the staff. (This note will be notes as appropriate. hidden, so a note off the staff will produce ledger lines.) #œ œ œ #œ œ œ #œ ‰ Œ Ó & œ & ®bœ œ #œ œ Œ Ó ®bœ œ #œ œ Œ Ó Step 4: Now hide the rests within beat 1 in top staff, and drag the second note to the place in the measure where the final note of the grouplet rests (the D here). Step 5: Feather and place the beaming as appropriate. * See note below. #œ #œ œ œ #œ #œ œ œ & œ Œ Ó œ Œ Ó ®bœ œ #œ œ Œ Ó ®bœ œ #œ œ Œ Ó & Step 7: Using the stem length tool, drag the stems of the quarter-note tuplets to the feathered beam as appropriate. The final note of the tuplet may need horizontal adjustment Step 6: Once the randomly inserted note is placed (step 4), to align with the end of the beam. -

Guitar Pro 7 User Guide 1/ Introduction 2/ Getting Started

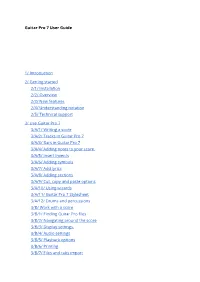

Guitar Pro 7 User Guide 1/ Introduction 2/ Getting started 2/1/ Installation 2/2/ Overview 2/3/ New features 2/4/ Understanding notation 2/5/ Technical support 3/ Use Guitar Pro 7 3/A/1/ Writing a score 3/A/2/ Tracks in Guitar Pro 7 3/A/3/ Bars in Guitar Pro 7 3/A/4/ Adding notes to your score. 3/A/5/ Insert invents 3/A/6/ Adding symbols 3/A/7/ Add lyrics 3/A/8/ Adding sections 3/A/9/ Cut, copy and paste options 3/A/10/ Using wizards 3/A/11/ Guitar Pro 7 Stylesheet 3/A/12/ Drums and percussions 3/B/ Work with a score 3/B/1/ Finding Guitar Pro files 3/B/2/ Navigating around the score 3/B/3/ Display settings. 3/B/4/ Audio settings 3/B/5/ Playback options 3/B/6/ Printing 3/B/7/ Files and tabs import 4/ Tools 4/1/ Chord diagrams 4/2/ Scales 4/3/ Virtual instruments 4/4/ Polyphonic tuner 4/5/ Metronome 4/6/ MIDI capture 4/7/ Line In 4/8 File protection 5/ mySongBook 1/ Introduction Welcome! You just purchased Guitar Pro 7, congratulations and welcome to the Guitar Pro family! Guitar Pro is back with its best version yet. Faster, stronger and modernised, Guitar Pro 7 offers you many new features. Whether you are a longtime Guitar Pro user or a new user you will find all the necessary information in this user guide to make the best out of Guitar Pro 7. 2/ Getting started 2/1/ Installation 2/1/1 MINIMUM SYSTEM REQUIREMENTS macOS X 10.10 / Windows 7 (32 or 64-Bit) Dual-core CPU with 4 GB RAM 2 GB of free HD space 960x720 display OS-compatible audio hardware DVD-ROM drive or internet connection required to download the software 2/1/2/ Installation on Windows Installation from the Guitar Pro website: You can easily download Guitar Pro 7 from our website via this link: https://www.guitar-pro.com/en/index.php?pg=download Once the trial version downloaded, upgrade it to the full version by entering your licence number into your activation window. -

Book Two Sample

BOOK TWO BOOK TWO JB’s modern notation method for Guitar $19.99 ISBN 978-1-7336076-1-2 51999 9781733607612 BOOK TWO table of contents Introduction • Tuning The Guitar 3-4 • Four Finger Tips 4 Chapter 11) • Triplets 5 • C♯ on the A-String and B-String 6 • E♭ on the D-String and B-String 6 Chapter 12) • Time Signatures 10 • 6/8 Time Signature 11 Chapter 13) • Sixteenth Notes 14 • Counting Sixteenth Notes and Rests 15 • Clapping Exercises (First Set) 16 Chapter 14) • More Sixteenth Note Goodness 19 • Clapping Exercises (Second Set) 20 Chapter 15) • G♯ on the Low E-String, G-String, and High E-String 22 • A♭ on the Low E-String, G-String, and High E-String 23 Chapter 16) • D♯ on the D-String, and B-String 26 • D♭ on the A-String, and B-String 26 • Syncopation 27 Chapter 17) • Performance Marks; Tempo 32 • Dynamic 34 • Endings; Articulation & Expression 36 • Place Markers 38 Chapter 18) • Position Playing On The Board 40 • A♯ and G♭ ALL OVER THE BOARD 41 • Revisiting “Old Friends” 43-45 Chapter 19) • E♯ and C♭ Introduced 45 • Odd Time Signatures 46 • Cut-Time (2/2 Time Signature) 49 Chapter 20) • B♯ and F♭ Introduced 52 • More On Triplets 54 Appendix • Lead Sheets 59 • Chord Diagrams 60-62 1 Keep These Points In Mind: • For all of us, most keys we read are not in C Major. And thankfully, not in C# or C♭, as well. • Push and challenge yourself to be very accustomed to keys other than C Major. -

Guide to Programming with Music Blocks Music Blocks Is a Programming Environment for Children Interested in Music and Graphics

Guide to Programming with Music Blocks Music Blocks is a programming environment for children interested in music and graphics. It expands upon Turtle Blocks by adding a collection of features relating to pitch and rhythm. The Turtle Blocks guide is a good place to start learning about the basics. In this guide, we illustrate the musical features by walking the reader through numerous examples. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Getting Started 2 Making a Sound 2.1 Note Value Blocks 2.2 Pitch Blocks 2.3 Chords 2.4 Rests 2.5 Drums 3 Programming with Music 3.1 Chunks 3.2 Musical Transformations 3.2.1 Step Pitch Block 3.2.2 Sharps and Flats 3.2.3 Adjust-Transposition Block 3.2.4 Dotted Notes 3.2.5 Speeding Up and Slowing Down Notes via Mathematical Operations 3.2.6 Repeating Notes 3.2.7 Swinging Notes and Tied Notes 3.2.8 Set Volume, Crescendo, Staccato, and Slur Blocks 3.2.9 Intervals and Articulation 3.2.10 Absolute Intervals 3.2.11 Inversion 3.2.12 Backwards 3.2.13 Setting Voice and Keys 3.2.14 Vibrato 3.3 Voices 3.4 Graphics 3.5 Interactions 4 Widgets 4.1 Monitoring status 4.2 Generating chunks of notes 4.2.1 Pitch-Time Matrix 4.2.2 The Rhythm Block 4.2.3 Creating Tuplets 4.2.4 What is a Tuplet? 4.2.5 Using Individual Notes in the Matrix 4.3 Generating rhythms 4.4 Musical Modes 4.5 The Pitch-Drum Matrix 4.6 Exploring musical proportions 4.7 Generating arbitrary pitches 4.8 Changing tempo 5 Beyond Music Blocks Many of the examples given in the guide have links to code you can run.