Music Notation Font Design: Technical Specifications for Note Head Font Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TIME SIGNATURES, TEMPO, BEAT and GORDONIAN SYLLABLES EXPLAINED

TIME SIGNATURES, TEMPO, BEAT and GORDONIAN SYLLABLES EXPLAINED TIME SIGNATURES Time Signatures are represented by a fraction. The top number tells the performer how many beats in each measure. This number can be any number from 1 to infinity. However, time signatures, for us, will rarely have a top number larger than 7. The bottom number can only be the numbers 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, et c. These numbers represent the note values of a whole note, half note, quarter note, eighth note, sixteenth note, thirty- second note, sixty-fourth note, one hundred twenty-eighth note, two hundred fifty-sixth note, five hundred twelfth note, et c. However, time signatures, for us, will only have a bottom numbers 2, 4, 8, 16, and possibly 32. Examples of Time Signatures: TEMPO Tempo is the speed at which the beats happen. The tempo can remain steady from the first beat to the last beat of a piece of music or it can speed up or slow down within a section, a phrase, or a measure of music. Performers need to watch the conductor for any changes in the tempo. Tempo is the Italian word for “time.” Below are terms that refer to the tempo and metronome settings for each term. BPM is short for Beats Per Minute. This number is what one would set the metronome. Please note that these numbers are generalities and should never be considered as strict ranges. Time Signatures, music genres, instrumentations, and a host of other considerations may make a tempo of Grave a little faster or slower than as listed below. -

Silent Music

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity Philosophy Faculty Research Philosophy Department Fall 2010 Silent Music Andrew Kania Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/phil_faculty Part of the Philosophy Commons Repository Citation Kania, A. (2010). Silent music. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 68(4), 343-353. doi:10.1111/ j.1540-6245.2010.01429.x This Post-Print is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Silent Music Andrew Kania [This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: Andrew Kania, “Silent Music” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 68 (2010): 343-53, which has been published in final form at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1540- 6245.2010.01429.x/abstract. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance with Wiley Terms and Conditions for Self-Archiving. Please cite only the published version.] Abstract In this essay, I investigate musical silence. I first discuss how to integrate the concept of silence into a general theory or definition of music. I then consider the possibility of an entirely silent musical piece. I begin with John Cage’s 4′33″, since it is the most notorious candidate for a silent piece of music, even though it is not, in fact, silent. I conclude that it is not music either, but I argue that it is a piece of non-musical sound art, rather than simply a piece of theatre, as Stephen Davies has argued. -

Music Braille Code, 2015

MUSIC BRAILLE CODE, 2015 Developed Under the Sponsorship of the BRAILLE AUTHORITY OF NORTH AMERICA Published by The Braille Authority of North America ©2016 by the Braille Authority of North America All rights reserved. This material may be duplicated but not altered or sold. ISBN: 978-0-9859473-6-1 (Print) ISBN: 978-0-9859473-7-8 (Braille) Printed by the American Printing House for the Blind. Copies may be purchased from: American Printing House for the Blind 1839 Frankfort Avenue Louisville, Kentucky 40206-3148 502-895-2405 • 800-223-1839 www.aph.org [email protected] Catalog Number: 7-09651-01 The mission and purpose of The Braille Authority of North America are to assure literacy for tactile readers through the standardization of braille and/or tactile graphics. BANA promotes and facilitates the use, teaching, and production of braille. It publishes rules, interprets, and renders opinions pertaining to braille in all existing codes. It deals with codes now in existence or to be developed in the future, in collaboration with other countries using English braille. In exercising its function and authority, BANA considers the effects of its decisions on other existing braille codes and formats, the ease of production by various methods, and acceptability to readers. For more information and resources, visit www.brailleauthority.org. ii BANA Music Technical Committee, 2015 Lawrence R. Smith, Chairman Karin Auckenthaler Gilbert Busch Karen Gearreald Dan Geminder Beverly McKenney Harvey Miller Tom Ridgeway Other Contributors Christina Davidson, BANA Music Technical Committee Consultant Richard Taesch, BANA Music Technical Committee Consultant Roger Firman, International Consultant Ruth Rozen, BANA Board Liaison iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .............................................................. -

SMT Sweelinck Paper Text SHORT V2

SMT Graduate Workshop Peter Schubert: Renaissance Instrumental Music November 7, 2014 Derek Reme! Musical Architecture in Three Domains: Stretto, Suspension, and Diminution in Sweelinck's Chromatic Fantasia Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck's Chromatic Fantasia is among the most famous keyboard works of the sixteenth century.1 It served as a model for instrumental polyphony that was imitated throughout Europe in the seventeenth century.2 The fantasia's subject is treated in augmentation and diminution in four rhythmic levels and also in four-voice stretto. The initial stretto passage, which is repeated in diminution in the final climax of the piece, contains an unusual accented dissonance; in this style, accented dissonance is reserved only for suspensions. There are three metrical levels of suspensions used throughout the piece, which parallel the four rhythmic levels of the subject's augmentation and diminution – only a whole note suspension is missing. I propose that the unusual accented dissonance in the first four-voice stretto passage is actually a rearticulated whole note suspension, representing the missing fourth metrical level in that domain. Therefore, this stretto passage combines two domains at their fourth and most heightened level: stretto in four voices and suspension at the whole note. This passage also represents a structural "pillar," which, through its repetition, divides the piece into three large sections. In addition, the middle section contains two analogous "internal pillars," which further subdivide the middle into three subsections. The last large-scale section, the climax, introduces subject stretto at the eighth note level, or !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! 1 Harold Vogel, "Sweelinck's 'Orfeo' Die 'Fantasia Crommatica,'" Musik in die Kirche, No. -

Notes, Rhythm, and Meter Notes

Dr. Barbara Murphy University of Tennessee School of Music NOTES, RHYTHM, AND METER NOTES: Notes represent a duration or length of a sound. Notes consist of the head the stem and the flag or beam. note = head + stem + flag NOTE HEADS: The head of the note should be written as an oval (not a round circle) and should be centered on the line or space of the staff that represents the note. STEMS: Stems are notated on the right side of the note head and are ascending if the note head is on the 3rd line of the staff or below that line. Stems are notated on the left side of the note head and are descending if the note is on the 3rd line of the staff or above that line. Stems should be about 1 octave in length and should be straight up and down (not slanted). FLAGS: Flags are notated to the right of the stem whether the stem is on the right or left side of the note head. BEAMS: Notes should be beamed together to show the beat. Beams should therefore not cross beats. Beams should be straight lines, not curves. Beams may be slanted ascending or descending according to the contour of the notes. Beaming notes together may result in shortened or elongated stems on some notes. If beaming eighth notes and sixteenth notes together, sixteenth note beams should always go inside the beginning and ending stems. DURATIONS: Notes can have various durations and various names: American British (older version) double-whole breve whole semi-breve half minim quarter crotchet eighth quaver sixteenth semi-quaver thirty-second demi-semi-quaver sixty-fourth hemi-demi-semi-quaver These notes look like the following: double whole half quarter 8th 16th 32nd 64th whole In the above list, each note duration is one-half the duration of the preceding note duration. -

Introduction to Braille Music Transcription

Introduction to Braille Music Transcription Mary Turner De Garmo Second Edition Revised and edited by Lawrence R. Smith Music Braille Transcriber Bettye Krolick Music Braille Consultant Beverly McKenney Music Braille Transcriber Sandra Kelly Music Braille Advisor Volume I National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped The Library of Congress Washington, DC 2005 Contents VOLUME I Foreword to the 1974 Edition . xi Preface to the 2005 Edition . xii Acknowledgments . xiii How to Use This Book . xiv Related Resources . xiv Overall Plan . xiv References to MBC-97 . xiv Using Computer Assistance . xv Taking the Course . xv References . xvi PART ONE: Basic Procedures and Transcribing Single-Staff Music 1 Formation of the Braille Note . 1 2 Eighth Notes, the Eighth Rest, and Other Basic Signs . 3 General Procedures . 4 Examples for Practice . 4 Procedures Specific to This Book . 7 Drills for Chapter 2 . 7 Exercises for Chapter 2 . 9 3 Quarter Notes, the Quarter Rest, and the Dot . 11 Examples for Practice . 11 Proofreading . 13 Drills for Chapter 3 . 13 Exercises for Chapter 3 . 15 4 Half Notes, the Half Rest, and the Tie . 17 Drills for Chapter 4 . 19 Exercises for Chapter 4 . 20 5 Whole and Double Whole Notes and Rests, Measure Rests, and Transcriber-Added Signs . 23 Various Print Methods for Showing Consecutive Measure Rests . 26 Reading Drill . 28 Drills for Chapter 5 . 30 Exercises for Chapter 5 . 31 6 Accidentals . 33 Directions for Brailling Accidentals . 33 Examples for Practice . 34 Drills for Chapter 6 . 35 i Exercises for Chapter 6 . 37 7 Octave Marks . 39 The Seven Octave Marks . -

1 an Important Component of Music Is the Rhythm, Or Duration of The

1 An important component of music is the rhythm, or duration of the sounds. We designate this with whole notes, half notes, quarter notes, eighth notes, etc., the names of which indicate the relative duration of notes (e.g., a half note lasts four times as long as an eighth note). ∼ 3 4 It isd of d courset t necessary to specify the actual (not just relative) duration of sounds. There are several ways to do this, we shall discuss two which reflect the manner in which music is displayed. Printed music groups notes into measures, and begins each line with a time signature which looks like a fraction, and specifies the number of notes in each measure. For example, the time signature 3/4 specifies that each measure contains three quarter notes (or six eighth notes, or a half note and a quarter note, or any collection of notes of equal total duration). (The above schematic is not divided into measures; a whole note would not fit within a measure in 3/4 time.) Indeed, you cannot tell from looking just at a measure whether the time signature is 3/4 or 6/8, but both the top and bottom of the time signature are important for specifying the nature of the rhythm. The top number specifies how many beats (or fundamental time units) there are in a measure, and the bottom number specifies which note represents the fundamental time unit. For example, 3/4 time specifies three beats to a measure with a quarter note representing one beat, 6/8 time specifies six beats to a measure with an eighth note representing one beat. -

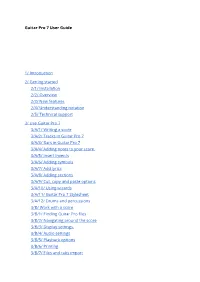

Guitar Pro 7 User Guide 1/ Introduction 2/ Getting Started

Guitar Pro 7 User Guide 1/ Introduction 2/ Getting started 2/1/ Installation 2/2/ Overview 2/3/ New features 2/4/ Understanding notation 2/5/ Technical support 3/ Use Guitar Pro 7 3/A/1/ Writing a score 3/A/2/ Tracks in Guitar Pro 7 3/A/3/ Bars in Guitar Pro 7 3/A/4/ Adding notes to your score. 3/A/5/ Insert invents 3/A/6/ Adding symbols 3/A/7/ Add lyrics 3/A/8/ Adding sections 3/A/9/ Cut, copy and paste options 3/A/10/ Using wizards 3/A/11/ Guitar Pro 7 Stylesheet 3/A/12/ Drums and percussions 3/B/ Work with a score 3/B/1/ Finding Guitar Pro files 3/B/2/ Navigating around the score 3/B/3/ Display settings. 3/B/4/ Audio settings 3/B/5/ Playback options 3/B/6/ Printing 3/B/7/ Files and tabs import 4/ Tools 4/1/ Chord diagrams 4/2/ Scales 4/3/ Virtual instruments 4/4/ Polyphonic tuner 4/5/ Metronome 4/6/ MIDI capture 4/7/ Line In 4/8 File protection 5/ mySongBook 1/ Introduction Welcome! You just purchased Guitar Pro 7, congratulations and welcome to the Guitar Pro family! Guitar Pro is back with its best version yet. Faster, stronger and modernised, Guitar Pro 7 offers you many new features. Whether you are a longtime Guitar Pro user or a new user you will find all the necessary information in this user guide to make the best out of Guitar Pro 7. 2/ Getting started 2/1/ Installation 2/1/1 MINIMUM SYSTEM REQUIREMENTS macOS X 10.10 / Windows 7 (32 or 64-Bit) Dual-core CPU with 4 GB RAM 2 GB of free HD space 960x720 display OS-compatible audio hardware DVD-ROM drive or internet connection required to download the software 2/1/2/ Installation on Windows Installation from the Guitar Pro website: You can easily download Guitar Pro 7 from our website via this link: https://www.guitar-pro.com/en/index.php?pg=download Once the trial version downloaded, upgrade it to the full version by entering your licence number into your activation window. -

Book Two Sample

BOOK TWO BOOK TWO JB’s modern notation method for Guitar $19.99 ISBN 978-1-7336076-1-2 51999 9781733607612 BOOK TWO table of contents Introduction • Tuning The Guitar 3-4 • Four Finger Tips 4 Chapter 11) • Triplets 5 • C♯ on the A-String and B-String 6 • E♭ on the D-String and B-String 6 Chapter 12) • Time Signatures 10 • 6/8 Time Signature 11 Chapter 13) • Sixteenth Notes 14 • Counting Sixteenth Notes and Rests 15 • Clapping Exercises (First Set) 16 Chapter 14) • More Sixteenth Note Goodness 19 • Clapping Exercises (Second Set) 20 Chapter 15) • G♯ on the Low E-String, G-String, and High E-String 22 • A♭ on the Low E-String, G-String, and High E-String 23 Chapter 16) • D♯ on the D-String, and B-String 26 • D♭ on the A-String, and B-String 26 • Syncopation 27 Chapter 17) • Performance Marks; Tempo 32 • Dynamic 34 • Endings; Articulation & Expression 36 • Place Markers 38 Chapter 18) • Position Playing On The Board 40 • A♯ and G♭ ALL OVER THE BOARD 41 • Revisiting “Old Friends” 43-45 Chapter 19) • E♯ and C♭ Introduced 45 • Odd Time Signatures 46 • Cut-Time (2/2 Time Signature) 49 Chapter 20) • B♯ and F♭ Introduced 52 • More On Triplets 54 Appendix • Lead Sheets 59 • Chord Diagrams 60-62 1 Keep These Points In Mind: • For all of us, most keys we read are not in C Major. And thankfully, not in C# or C♭, as well. • Push and challenge yourself to be very accustomed to keys other than C Major. -

Numbers and Tempo: 1630-1800 Beverly Jerold

Performance Practice Review Volume 17 | Number 1 Article 4 Numbers and Tempo: 1630-1800 Beverly Jerold Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Jerold, Beverly (2012) "Numbers and Tempo: 1630-1800," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 17: No. 1, Article 4. DOI: 10.5642/ perfpr.201217.01.04 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol17/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Numbers and Tempo: 1630-1800 Beverly Jerold Copyright © 2012 Claremont Graduate University Ever since antiquity, the human species has been drawn to numbers. In music, for example, numbers seem to be tangible when compared to the language in early musical texts, which may have a different meaning for us than it did for them. But numbers, too, may be misleading. For measuring time, we have electronic metronomes and scientific instruments of great precision, but in the time frame 1630-1800 a few scientists had pendulums, while the wealthy owned watches and clocks of varying accuracy. Their standards were not our standards, for they lacked the advantages of our technology. How could they have achieved the extremely rapid tempos that many today have attributed to them? Before discussing the numbers in sources thought to support these tempos, let us consider three factors related to technology: 1) The incalculable value of the unconscious training in every aspect of music that we gain from recordings. -

Review of Musical Rhythm Symbols and Counting Rhythm Symbols Tell Us How Long a Note Will Be Held

Review of Musical Rhythm Symbols and Counting Rhythm symbols tell us how long a note will be held. Rhythm is measured in beats. This is our unit of measurement in music for rhythm. Some rhythms have a value that is greater than one beat. Here are some examples: Whole Note u The Whole Note is worth four beats of sound. It contains the counts 1, 2, 3, 4. 1 2 3 4 Half Note u The Half Note is worth two beats of sound. It contains the counts 1, 2. 1 2 Dotted Rhythms u The Dotted Half Note is equal to a half note note tied to a quarter note. It has the value of three beats. 3 2 1 u The Dotted Quarter Note is equal to a quarter note tied to an eighth note. It has the value of 1 ½ beats. 1 ½ 1 ½ Rhythms worth one beat: Quarter Note u The Quarter Note is worth one beat. u It has one sound on the beat. u It will have a number as its count. (1, 2, 3 or 4) 1 2 3 4 Rhythms worth one beat: Eighth Notes u Two Eighth Notes are worth one beat. u It has two sounds on the beat. u First note has the # on it. u Second note has + on it 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + Rhythms worth one beat: Sixteenth Notes u Four Sixteenth notes are worth one beat. u It has four sounds on the beat. u First note has the # on it. u Second note has “e” on it. -

Musical Symbols Range: 1D100–1D1FF

Musical Symbols Range: 1D100–1D1FF This file contains an excerpt from the character code tables and list of character names for The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 This file may be changed at any time without notice to reflect errata or other updates to the Unicode Standard. See https://www.unicode.org/errata/ for an up-to-date list of errata. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/ for access to a complete list of the latest character code charts. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/Unicode-14.0/ for charts showing only the characters added in Unicode 14.0. See https://www.unicode.org/Public/14.0.0/charts/ for a complete archived file of character code charts for Unicode 14.0. Disclaimer These charts are provided as the online reference to the character contents of the Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 but do not provide all the information needed to fully support individual scripts using the Unicode Standard. For a complete understanding of the use of the characters contained in this file, please consult the appropriate sections of The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0, online at https://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode14.0.0/, as well as Unicode Standard Annexes #9, #11, #14, #15, #24, #29, #31, #34, #38, #41, #42, #44, #45, and #50, the other Unicode Technical Reports and Standards, and the Unicode Character Database, which are available online. See https://www.unicode.org/ucd/ and https://www.unicode.org/reports/ A thorough understanding of the information contained in these additional sources is required for a successful implementation.