Implementation Strategy and Cost of Mozambique's HPV Vaccine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gavi's Vaccine Investment Strategy

Gavi’s Vaccine Investment Strategy Deepali Patel THIRD WHO CONSULTATION ON GLOBAL ACTION PLAN FOR INFLUENZA VACCINES (GAP III) Geneva, Switzerland, 15-16 November 2016 www.gavi.org Vaccine Investment Strategy (VIS) Evidence-based approach to identifying new vaccine priorities for Gavi support Strategic investment Conducted every 5 years decision-making (rather than first-come- first-serve) Transparent methodology Consultations and Predictability of Gavi independent expert advice programmes for long- term planning by Analytical review of governments, industry evidence and modelling and donors 2 VIS is aligned with Gavi’s strategic cycle and replenishment 2011-2015 Strategic 2016-2020 Strategic 2021-2025 period period 2008 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024 2025 RTS,S pilot funding decision VIS #1 VIS #2 VIS #3 MenA, YF mass campaigns, JE, HPV Cholera stockpile, Mid 2017 : vaccine ‘long list’ Rubella, Rabies/cholera studies, Oct 2017 : methodology Typhoid Malaria – deferred Jun 2018 : vaccine shortlist conjugate Dec 2018 : investment decisions 3 VIS process Develop Collect data Develop in-depth methodology and Apply decision investment decision framework for cases for framework with comparative shortlisted evaluation analysis vaccines criteria Phase I Narrow long list Phase II Recommend for Identify long list to higher priority Gavi Board of vaccines vaccines approval of selected vaccines Stakeholder consultations and independent expert review 4 Evaluation criteria (VIS #2 – 2013) Additional Health Implementation -

Even Partial COVID-19 Vaccination Protects Nursing Home Residents

News & Analysis News From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Even Partial COVID-19 Vaccination lence of underlying medical conditions,” the Protects Nursing Home Residents authors wrote. A CDC analysis has shown that a single dose Waning COVID-19 cases as more resi- of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine dents and staff received second vaccina- protected medically vulnerable nursing tions made it impossible to assess vaccine ef- home residents as well as it did general adult fectiveness after 2 doses. Evidence from populations that were evaluated in other ef- previous studies demonstrated greater pro- ficacy and effectiveness studies. tection among older adults after a second The analysis helps fill a data gap about dose, suggesting that completing the 2-dose vaccine effectiveness in this high-risk regimen may be particularly important to group—generally older, frail adults with un- protect long-term care facility residents, the derlying health conditions—who were left authors suggested. out of COVID-19 vaccine trials. Excluding older adults from the trials raised questions Vaccine Dramatically Reduces HPV about how well nursing home residents Infection Among Young Women would respond to vaccination. Widespread vaccination of young women By analyzing the Pfizer-BioNTech vac- against human papillomavirus (HPV) has led cine’sperformanceduringalateJanuaryout- to a greater than 80% reduction in infec- the 4 HPV strains most likely to cause dis- break at 2 Connecticut skilled nursing facili- tions with the 4 strains most often associ- ease. Newer versions that protect against 9 ties, investigators from the CDC and the ated with disease, according to a CDC study. -

Yellow Fever 2016

Resident / Humanitarian Coordinator Report on the use of CERF funds RESIDENT / HUMANITARIAN COORDINATOR REPORT ON THE USE OF CERF FUNDS ANGOLA RAPID RESPONSE YELLOW FEVER 2016 RESIDENT/HUMANITARIAN COORDINATOR Pier Paolo Balladelli REPORTING PROCESS AND CONSULTATION SUMMARY a. Please indicate when the After Action Review (AAR) was conducted and who participated. Review agreed on 02/09/2016 and 07/09/2016. b. Please confirm that the Resident Coordinator and/or Humanitarian Coordinator (RC/HC) Report was discussed in the Humanitarian and/or UN Country Team and by cluster/sector coordinators as outlined in the guidelines. YES NO c. Was the final version of the RC/HC Report shared for review with in-country stakeholders as recommended in the guidelines (i.e. the CERF recipient agencies and their implementing partners, cluster/sector coordinators and members and relevant government counterparts)? YES NO Final version shared with UNICEF and UNDP, although this initiative was mainly implemented by WHO 2 I. HUMANITARIAN CONTEXT TABLE 1: EMERGENCY ALLOCATION OVERVIEW (US$) Total amount required for the humanitarian response: Source Amount CERF 3,000,000 Breakdown of total response COUNTRY-BASED POOL FUND (if applicable) 4,508,559 funding received by source OTHER (bilateral/multilateral) TOTAL 10,473,618 *The total amount does not match because this was considered an underfunded emergency. TABLE 2: CERF EMERGENCY FUNDING BY ALLOCATION AND PROJECT (US$) Allocation 1 – date of official submission: 06/04/2016- 05/10/2016 Agency Project code Cluster/Sector -

HPV – Facts About the Virus, the Vaccine and What This Means For

The WHO Regional The World Health Organization (WHO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations created in 1948 with the primary responsibility for international health matters each with its own programme geared to the particular health conditions of the countries it serves. Member States Albania Andorra Armenia Austria Azerbaijan Belarus Belgium Bosnia and Herzegovina Bulgaria Croatia Cyprus Czechia HPV – facts about the virus, Denmark Estonia Finland France the vaccine and what this Georgia Germany Greece means for you Hungary Iceland Ireland Israel Italy Kazakhstan Kyrgyzstan Answers to common questions Latvia Lithuania asked by adolescents and Luxembourg Malta young adults Monaco Montenegro Netherlands Norway Poland Portugal Republic of Moldova Romania Russian Federation San Marino Serbia Slovakia Slovenia Spain Sweden Switzerland Tajikistan The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia Turkey Turkmenistan Ukraine United Kingdom UN City, Marmorvej 51, DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø, Denmark Uzbekistan Tel.: +45 45 33 70 00 Fax: +45 45 33 70 01 E-mail: [email protected] Q&A: Answers to common questions asked by adolescents and young adults HPV and vaccination HPV stands for human papillomavirus. There are over What is HPV and why should I be vaccinated 200 known types of the virus, 30 of which are transmitted against it? through sexual activity. HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the world. Almost 80% of sexually active people will get infected with one or more HPV types in their lifetime. HPV infection can lead to several types of cancer and genital warts. Cervical cancer is the most common type of cancer caused by HPV, and it is the fourth most common cancer in women worldwide. -

Hanna Nohynek @Hnohynek

Biosketch Hanna Nohynek @hnohynek Hanna Nohynek is Chief Physician and Deputy Head of the Infectious Diseases Control and Vaccines Unit of the Department of Health Security at the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare. She serves as secretary of the Finnish NITAG (KRAR), and leads the subgroup on Strategic development of the influenza vaccination programme and the subgroup on the SARS-CoV-2 vaccination strategy. She practices clinical medicine at a travel health clinic in Aava, Helsinki. She was instrumental in designing the first THL (KTL) health advisory for refugees and asylum seekers in Finland, studying the narcolepsy signal post pandemic vaccination, designing the introduction of the HPV vaccine to the national immunization programme, and the introduction of the live attenuated influenza vaccine for children. Her present research interests are register-based vaccine impact studies, evidence based policy/decision making, vaccine safety, hesitancy, SARS-CoV-2, RSV, influenza and pneumococcus. She coordinates the work packages on field studies and communication for IMI DRIVE on brand specific influenza vaccine effectiveness (www.drive-eu.org). She has authored more than 130 original articles (including the first scientific report on the association between pandemic influenza vaccination and narcolepsy), and she teaches, giving over 30 invited lectures annually and guiding elective, graduate and PhD students (presently Raija Auvinen and Idil Hussein). She belongs to the external faculty of the University of Tampere MSc course on Global Health. She has served on expert committees evaluating HBV, PCV and rota virus vaccines in Finland, and as an advisor to the EU, IMI, IVI, WHO, GAVI, SIDA/SRC, and the Finnish MOFA. -

Considerations for Causality Assessment of Neurological And

Occasional essay J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp-2021-326924 on 6 August 2021. Downloaded from Considerations for causality assessment of neurological and neuropsychiatric complications of SARS- CoV-2 vaccines: from cerebral venous sinus thrombosis to functional neurological disorder Matt Butler ,1 Arina Tamborska,2,3 Greta K Wood,2,3 Mark Ellul,4 Rhys H Thomas,5,6 Ian Galea ,7 Sarah Pett,8 Bhagteshwar Singh,3 Tom Solomon,4 Thomas Arthur Pollak,9 Benedict D Michael,2,3 Timothy R Nicholson10 For numbered affiliations see INTRODUCTION More severe potential adverse effects in the open- end of article. The scientific community rapidly responded to label phase of vaccine roll- outs are being collected the COVID-19 pandemic by developing novel through national surveillance systems. In the USA, Correspondence to SARS- CoV-2 vaccines (table 1). As of early June Dr Timothy R Nicholson, King’s roughly 372 adverse events have been reported per College London, London WC2R 2021, an estimated 2 billion doses have been million doses, which is a lower rate than expected 1 2LS, UK; timothy. nicholson@ administered worldwide. Neurological adverse based on the clinical trials.6 kcl. ac. uk events following immunisation (AEFI), such as In the UK, adverse events are reported via the cerebral venous sinus thrombosis and demyelin- MB and AT are joint first Coronavirus Yellow Card reporting website. As of ating episodes, have been reported. In some coun- authors. early June 2021, approximately 250 000 Yellow tries, these have led to the temporary halting of BDM and TRN are joint senior Cards have been submitted, equating to around authors. -

UNEP Mercury Treaty Protects Access to Thiomersal-Containing Vaccines

UNEP mercury treaty protects access to thiomersal-containing vaccines United Nations Environment Program has developed a treaty on mercury in an effort to protect human health and the environment by limiting mercury releases. In the course of the negotiations, a proposal was made to restrict vaccines that contain the preservative thiomersal under a section of the treaty that prohibits trade of mercury-added products. The implications of restricting thiomersal, an ethyl mercury-containing preservative, would be significant. According to SAGE, “Thiomersal-containing vaccines [are] safe, essential, and irreplaceable components of immunization programs, especially in developing countries, and…removal of these products would disproportionately jeopardize the health and lives of the most disadvantaged children worldwide.” The treaty annex that describes prohibited products specifically excludes “vaccines containing thiomersal as preservatives” under a short list of products the authors intended to emphasize were to be protected. Protecting access to vaccines came as the result of a strong partnership between WHO, UNICEF, GAVI, and civil society advocates and experts around the world to educate country delegates, who predominantly came from ministries of environment. This was also a wonderful partnership with animal health experts, who similarly rely on thiomersal for veterinary vaccines. By facilitating communication between ministries of health and ministries of environment, strong statements are made by delegates about the essential role of thiomersal-containing vaccines in protecting human health. PATH will be collecting and disseminating additional information about how the community came together around this issue and lessons learned in the coming months. . -

Supplemental Information and Guidance for Vaccination Providers Regarding Use of 9-Valent HPV Vaccine

Supplemental information and guidance for vaccination providers regarding use of 9-valent HPV A 9-valent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine (9vHPV, Gardasil 9, Merck & Co.) was licensed for use in females and males in December 2014.1,2,3,4 The 9vHPV was the third HPV vaccine licensed in the United States by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA); the other vaccines are bivalent HPV vaccine (2vHPV, Cervarix, GlaxoSmithKline), licensed for use in females, and quadrivalent HPV vaccine (4vHPV, Gardasil, Merck & Co.), licensed for use in females and males.5 In February 2015, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended 9vHPV as one of three HPV vaccines that can be used for routine vaccination of females and one of two HPV vaccines for routine vaccination of males.6 After the end of 2016, only 9vHPV will be distributed in the United States. In October 2016, ACIP updated HPV vaccination recommendations regarding dosing schedules.7 CDC now recommends two doses of HPV vaccine (0, 6–12 month schedule) for persons starting the vaccination series before the 15th birthday. Three doses of HPV vaccine (0, 1–2, 6 month schedule) continue to be recommended for persons starting the vaccination series on or after the 15th birthday and for persons with certain immunocompromising conditions. Guidance is needed for persons who started the series with 2vHPV or 4vHPV and may be completing the series with 9vHPV. The information below summarizes some of the recommendations included in ACIP Policy Notes and provides additional guidance.5-7 Information about the vaccines What are some of the similarities and differences between the three HPV vaccines? y Each of the three HPV vaccines is a noninfectious, virus-like particle (VLP) vaccine. -

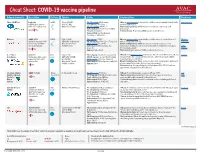

Cheat Sheet: COVID-19 Vaccine Pipeline

Cheat Sheet: COVID-19 vaccine pipeline Primary sponsor(s) Description Platform Funders Status Considerations Read more Pfizer / BioNTech Comirnaty mRNA Pfizer ($500M) Ph. I/II ongoing: 456/Germany Efficacy: Interim analysis shows that the candidate was safe and well-tolerated with New York Times mRNA that encodes for USG ($1.9M) Ph. II planned: 960/China an efficacy rate of 95%. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Warp Speed Finalist Ph. II/III ongoing: 44K US +5 Manufacturing/delivery: mRNA vaccines are relatively easy to scale and Authorization: EUA in EU, US, +9; WHO manufacture. Emergency Validation Platform history: No previous mRNA vaccines licensed for use. Approval: Bahrain, New Zealand, Saudi Arabia, Switzerland Moderna mRNA-1273 mRNA USG ($2.48B) Ph. I ongoing: 155/US Efficacy: Interim analysis shows that the candidate was safe and well-tolerated Moderna Synthetic messenger RNA CEPI/GAVI (Undisclosed) Ph. II/III ongoing: 3000 (12 to 17 years)/ US with an efficacy rate of 94.5%. Statement that encodes for SARS- Warp Speed Finalist Ph. III ongoing: 30,000/US Manufacturing/delivery: mRNA vaccines are relatively easy to scale and CoV-2 spike protein. COVAX Portfolio Authorization: EUA in Canada, EU, manufacture (potential for 1B doses by 2022); likely to require two doses, but a AVAC Israel, US third may be necessary. Webinar Approval: Switzerland Platform history: No previous mRNA vaccines licensed for use. U. of Oxford AZD1222 Viral USG ($1.2B) Ph. II ongoing: 300 vols (6-17 years)/ UK Efficacy: Ph. III interim analysis shows vaccine was safe and well-tolerated, efficacy Science AstraZeneca Chimpanzee Adeno vector vector CEPI/GAVI ($750M) Ph. -

Yellow Fever Vaccine

Yellow Fever Vaccine: Current Supply Outlook UNICEF Supply Division May 2016 0 Yellow Fever Vaccine - Current Supply Outlook May 2016 This update provides revised information on yellow fever vaccine supply availability and increased demand. Despite slight improvements in availability and the return of two manufacturers from temporary suspension, a constrained yellow fever vaccine market will persist through 2017, exacerbated by current emergency outbreak response requirements. 1. Summary Yellow fever vaccine (YFV) supply through UNICEF remains constrained due to limited production capacity. Despite the return of two manufacturers from temporary suspension, the high demand currently generated from the yellow fever (YF) outbreak in Angola, in addition to potential increased outbreak response requirements in other geographic regions, outweigh supply. The demand in response to the current YF outbreak in Angola could negatively impact the supply availability for some routine immunization programme activities. UNICEF anticipates a constrained global production capacity to persist through 2017. UNICEF has long-term arrangements (LTAs) with four YFV suppliers to cover emergency stockpile, routine immunization, and preventative campaign requirements. During 2015, UNICEF increased total aggregate awards to suppliers to reach approximately 98 million doses for 2016- 2017. However, whereas supply can meet emergency stockpile and routine requirements, it is insufficient to meet all preventive campaign demands, which increased the total demand through UNICEF to 109 million doses. The weighted average price (WAP) per dose for YFV increased 7% a year on average since 2001, from US$ 0.39 to reach US$ 1.04 in 2015. Given the continued supply constraints, UNICEF anticipates a YFV WAP per dose of US$1.10 in the near-term. -

An Overview of COVID Vaccine Clinical Trial Results & Some Challenges

An overview of COVID vaccine clinical trial results & some challenges DCVMN Webinar December 8th, 2020 Access to COVID-19 tools ACCESSACCESS TO TOCOVID-19 COVID-19 TOOLS TOOLS (ACT) (ACT) ACCELERATOR ACCELERATOR (ACT) accelerator A GlobalA GlobalCollaboration Collaboration to Accelerate tothe AccelerateDevelopment, the Production Development, and Equitable Production Access to New and Equitable AccessCOVID-19 to New diagnostics, COVID-19 therapeutics diagnostics, and vaccines therapeutics and vaccines VACCINES DIAGNOSTICS THERAPEUTICS (COVAX) Development & Manufacturing Led by CEPI, with industry Procurement and delivery at scale Led by Gavi Policy and allocation Led by WHO Key players SOURCE: (ACT) ACCELERATOR Commitment and Call to Action 24th April 2020 ACT-A / COVAX governance COVAX COORDINATION MEETING CEPI Board Co-Chair: Jane Halton Co-Chair: Dr. Ngozi Gavi Board Workstream leads + DCVMN and IFPMA-selected Reps As needed – R&D&M Chair; COVAX IPG Chair Development & Manufacturing Procurement and delivery Policy and allocation (COVAX) at scale Led by (with industry) Led by Led by R&D&M Investment Committee COVAX Independent Product Group Technical Review Group Portfolio Group Vaccine Teams SWAT teams RAG 3 COVAX SWAT teams are being set up as a joint platform to accelerate COVID- 19 Vaccine development and manufacturing by addressing common challenges together Timely and targeted Multilateral Knowledge-based Resource-efficient Addresses specific cross- Establishes a dialogue Identifies and collates Coordinates between developer technical and global joint effort most relevant materials different organizations/ challenges as they are across different COVID-19 and insights across the initiatives to limit raised and/or identified vaccines organizations broader COVID-19 duplications and ensure on an ongoing basis (incl. -

Human Papillomavirus Vaccine

Human Papillomavirus Vaccine: Supply and Demand Update UNICEF Supply Division October 2020 0 Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Supply and Demand Update - October 2020 This update provides information on human papillomavirus vaccine, including supply, demand, and pricing trends. It highlights continued supply constraints foreseen over 2020 and 2021, which also affects countries procuring through UNICEF. UNICEF requests self-financing middle-income countries to consolidate credible multi-year demand and to submit multi-year commitments through UNICEF. 1. Summary • UNICEF’s strategic plan for 2018-2021 seeks to ensure that at least 24 countries nationally introduce human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine into their immunization programmes.1 As of to date, 20 countries supplied through UNICEF, of which 15 supported by Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance (Gavi) and five countries having transitioned from Gavi support and self-finance their procurement, have introduced HPV vaccines since 2013. Fourteen middle-income countries (MICs) are also procuring HPV vaccines through UNICEF. From 2013 to 2019, UNICEF’s total HPV vaccine procurement reached 30.9 million doses in support of girls. There is currently no gender-neutral programmes in countries supplied through UNICEF. Of the 30.9 million doses, UNICEF procured 28.3 million doses (91 per cent) for countries supported by Gavi, including those that transitioned from Gavi support and still access Gavi prices, and 2.6 million doses (9 per cent) on behalf of self-financing MICs. • In December 2016, Gavi revised its programme strategy to support full-scale national HPV vaccine introductions with multi-age cohort (MAC) vaccinations. This substantially increased HPV vaccine demand through UNICEF from 2017.