Whaler Yeomen of Cape May

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Laurence Bergreen D D Rio De La Plata Rio De La Plata Cape of Good Hope,Cape of Good Hope, O O N N I I C C Mocha Is

90˚ 105˚90˚ 120˚105˚ 135˚ 120˚150˚ 135˚ 165˚150˚ 180˚ 165˚165˚ 180˚ 150˚165˚ 135˚150˚ 120˚135˚ 120˚ 90˚ 75˚ 90˚ 60˚75˚ 45˚ 60˚30˚ 45˚ 15˚ 30˚0˚ 15˚ 15˚ 0˚30˚ 15˚ 45˚ 30˚60˚ 45˚ 60˚ 75˚ 75˚ 75˚ 75˚ 70˚ 70˚FranFrancis Drciaks Dre’sake’s 70˚ 70˚ CircumCircnaumviganativiongation of thofe Wotherl Wod rld ARCTIC CIRCLE ARCTIC CIRCLE Nov. 15No77v.–S 15ep77t.–S 15ep80t. 1580 60˚ 60˚ 60˚ 60˚ ENGLAND ENGLAND NORTH NORTH EUROPE EUROPE Plymouth, Sept. Plymouth,26, 1580 Sept. 26, 1580 Nov. 15, 1577 Nov. 15, 1577 45˚ 45˚ Terceira, Azores Terceira, Azores 45˚ 45˚ ASIA ASIA Sept. 11, 1580 Sept. 11, 1580 New Albion New Albion AMERICA AMERICAA A June–July 1579 June–July 1579 t l t l a n a n t t i c i c Mogador Is. MoCapegador Cantin Is. Cape Cantin 30˚ 30˚ O O 30˚ 30˚ c c e e a a n n Cape Barbas Cape Barbas In Search of a CapeKingdom Verde IslandsCape Verde Islands 15˚ 15˚ Philippines Philippines 15˚ 15˚ ? ? PANAMA PANAMA AFRICA AFRICA Guatulco Guatulco SIERRA SIERRA Mindanao Mindanao Equator crossed Equator crossed LEONE LEONE Palau, Sept. 30, Pa1579lau, Sept. 30, 1579 P a c P a c i f i i f i Caño Is. Caño Is. FrAncisFeb. 20, 1578 Fe b.DrAke, 20, 1578 elizAbeth i, AnD the c c March 16, 1579 March 16, 1579 0˚ 0˚ Ternate Ternate O O EQUATOR 0˚ EQUATOR 0˚ c e c e Sumatra Sumatra a a Fernando de NoronhFernaando de Noronha n n Paita Paita Perilous birth oF the british emPire Java Java PERU SOPEUTRUH SOUTH March 26, 1580 March 26, 1580 Lima, El Callao Lima, El CallaoAMERICA AMERICA n n 15˚ 15˚ 15˚ 15˚ a a e e Henderson Is. -

New Albion P1

State of California The Resources Agency Primary # DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION HRI # PRIMARY RECORD Trinomial NRHP Status Code Other Listings Review Code Reviewer Date Page 2 of 30 *Resource Name or #: (Assigned by recorder) Site of New Albion P1. Other Identifier: ____ *P2. Location: Not for Publication Unrestricted *a. County Marin and (P2c, P2e, and P2b or P2d. Attach a Location Map as necessary.) *b. USGS 7.5' Quad Date T ; R ; of of Sec ; B.M. c. Address 1 Drakes Beach Road City Inverness Zip 94937 d. UTM: (Give more than one for large and/or linear resources) Zone , mE/ mN e. Other Locational Data: (e.g., parcel #, directions to resource, elevation, decimal degrees, etc., as appropriate) Site bounded by 38.036° North latitude, -122.590° West longitude, 38.030° North ° latitude, and -122.945 West longitude. *P3a. Description: (Describe resource and its major elements. Include design, materials, condition, alterations, size, setting, and boundaries) Site of Francis Drake’s 1579 encampment called “New Albion” by Drake. Includes sites of Drake’s fort, the careening of the Golden Hind, the abandonment of Tello’s bark, and the meetings with the Coast Miwok peoples. Includes Drake’s Cove as drawn in the Hondius Broadside map (ca. 1595-1596) which retains very high integrity. P5a. Photograph or Drawing (Photograph required for buildings, structures, and objects.) Portus Novae Albionis *P3b. Resource Attributes: (List attributes and codes) AH16-Other Historic Archaeological Site DPR 523A (9/2013) *Required information State of California The Resources Agency Primary # DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION HRI # PRIMARY RECORD Trinomial NRHP Status Code Other Listings Review Code Reviewer Date Page 3 of 30 *Resource Name or #: (Assigned by recorder) Site of New Albion P1. -

Acts of the Commissioners of the United Colonies of New England

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ..CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 3 1924 083 937 122 Cornell University Library ^^ The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924083937122 RECORDS OF PLYMOUTH COLONY. %tk of i\t Comittissioitfi's of !lje Initfb Colonies of felo €\4ml YOL. I. ] 643-1051. RECORDS OF THE COLONY OF NEW PLYMOUTH IN NEW ENGLAND. PRINTED BY ORDER OF THE LEGISLATURE OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS. EDITED BY DAVID PULSIFER, CLERK IN THE OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY OF THE COMMONWEALTH, MEMBER OF THE NEW ENGLAND HISTORIC-GENEALOfilCAL SOCIETY, VIXLOW OP TllK AMERICAN STATISTICAL ASSOCIATION, CORKESPONDINQ MEMBER OP THE ESSEX INSTITUTE, AND OF THE RHODE ISLAND, NEW YORK, COXNKCTICUT AND WISCONSIN BISTORICAL SOCIETIES. %t\^ of Jlje ^tinimissioners of Ijje InM Colonirs of Btfo ^iiglank VOL. I. 1643-1651. BOSTON: FROM THE PRESS OF WILLIAM WHITE, rRINTEK TO THE COMMONWEALTH. 185 9. ^CCRMELL^ ;UNIVERSITY LJ BRARY C0MM0.\))EALT11 OF MASSACHUSETTS. ^etrflarn's f eprtnunt. Boston, Apkil o, 1858. By virtue of Chapter forty-one of the Eesolves of the year one thousand eight hundred fifty-eight, I appoint David Pulsifee, Esq., of Boston, to super- intend the printing of the New Plymouth Records, and to proceed with the copying, as provided in previous resolves, in such manner and form as he may consider most appropriate for the undertaking. Mr. Pulsifer has devoted many years to the careful exploration and transcription of ancient records, in the archives of the County Courts and of the Commonwealth. -

Diamonds in the Sand

I was hooked. A real treasure hunt. Following his directions, I made my way to the gift shops at Sunset Beach to learn more about the Cape May diamonds. There, I found faceted and mounted gems and books, including The Legend of the Cape May Diamond, by award- winning writer Trinka Hakes Noble. Just like real diamonds To the naked eye viewing a polished and faceted Cape May diamond, there is no distinguishable difference between it and a real diamond. Until modern gem scanning equipment was developed, they were passed along by unscrupulous vendors as genuine diamonds. As closely as I examined the stones, I could not tell the difference either. They sparkle as brilliantly as any engagement ring, but sadly, unlike true diamonds, have no substantial value. According to legend and local history, Cape May diamonds are pure quartz crystal, and look like clear pebbles along the beach. When wet, they are translucent in hues of white, beige and rose, polished smooth by the ocean waves and sand. Often mistaken for river-smoothed glass from New Jersey’s once-thriving glass manufacturing industry, BY LINDA BARRETT geologists claim the crystals are local in origin, washing out of nearby Pleistocene gravel deposits. They register an eight on the hardness scale. Claims are their source is over 200 miles away, in the upper reaches of the Delaware River. “The Cape May diamonds are the daughters of the river, linking the state’s past and present. These Diamonds in the Sand fragments of quartz rock have hidden in the river, plucked away from the Cape May Diamonds Dazzle Visitors mountains lining its banks,” says author Noble. -

The Colorado College Music Department Presents the Bowed Piano Ensemble's Ninth Europe Tour Preview Concert

The Colorado College Music Department presents The Bowed Piano Ensemble’s Ninth Europe tour preview concert Stephen Scott, Founder, Director and Composer Victoria Hansen, soprano During the next two weeks, this program will be performed in London, Italy and Malta The Ensemble: Zachary Bellows, Connor Rice, Neil Hesse, Andrew Pope, Saraiya Ruano, Hadar Zeigerson, Drew Campbell, Sylvie Scowcroft, Trisha Andrews, Stephen Scott Thursday, March 7, 2013 7:30 PM Packard Hall PROGRAM New York Drones (2006) The Ensemble premiered this piece on October 26 and 28, 2006 at Cincinnati’s Contemporary Arts Center and the Allen Room, Frederick P. Rose Hall, Home of Jazz at Lincoln Center, in New York. The work is dedicated to the great American composer Steve Reich in honor of his seventieth birthday that month. Without his brilliant and sustained vision, our contemporary musical language would be much poorer. I personally owe Steve a great debt of gratitude; as a young and inexperienced composer, I went to Ghana in 1970 to study polyrhythmic drumming and, by chance, met Steve, who was there for the same reason and whom I knew of and admired for his early minimalist compositions Come Out and Violin Phase. He took me under his wing and gave me a listening and score-reading tour of his current work. Later I collaborated with Terry Riley, one of Steve’s important influences, and the music of these two composers, along with jazz, became my most significant inspiration as I began to develop my own musical ideas. In this piece I have interpreted the concept of drones quite liberally to encompass not only long sustained tones but also repeating rhythms on one pitch or repeating melodic and harmonic patterns in a single mode. -

(King Philip's War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial

Connecticut Unscathed: Victory in The Great Narragansett War (King Philip’s War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Major Jason W. Warren, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: John F. Guilmartin Jr., Advisor Alan Gallay, Kristen Gremillion Peter Mansoor, Geoffrey Parker Copyright by Jason W. Warren 2011 Abstract King Philip’s War (1675-1676) was one of the bloodiest per capita in American history. Although hostile native groups damaged much of New England, Connecticut emerged unscathed from the conflict. Connecticut’s role has been obscured by historians’ focus on the disasters in the other colonies as well as a misplaced emphasis on “King Philip,” a chief sachem of the Wampanoag groups. Although Philip formed the initial hostile coalition and served as an important leader, he was later overshadowed by other sachems of stronger native groups such as the Narragansetts. Viewing the conflict through the lens of a ‘Great Narragansett War’ brings Connecticut’s role more clearly into focus, and indeed enables a more accurate narrative for the conflict. Connecticut achieved success where other colonies failed by establishing a policy of moderation towards the native groups living within its borders. This relationship set the stage for successful military operations. Local native groups, whether allied or neutral did not assist hostile Indians, denying them the critical intelligence necessary to coordinate attacks on Connecticut towns. The English colonists convinced allied Mohegan, Pequot, and Western Niantic warriors to support their military operations, giving Connecticut forces a decisive advantage in the field. -

Puritan New England: Plymouth

Puritan New England: Plymouth A New England for Puritans The second major area to be colonized by the English in the first half of the 17th century, New England, differed markedly in its founding principles from the commercially oriented Chesapeake tobacco colonies. Settled largely by waves of Puritan families in the 1630s, New England had a religious orientation from the start. In England, reform-minded men and women had been calling for greater changes to the English national church since the 1580s. These reformers, who followed the teachings of John Calvin and other Protestant reformers, were called Puritans because of their insistence on purifying the Church of England of what they believed to be unscriptural, Catholic elements that lingered in its institutions and practices. Many who provided leadership in early New England were educated ministers who had studied at Cambridge or Oxford but who, because they had questioned the practices of the Church of England, had been deprived of careers by the king and his officials in an effort to silence all dissenting voices. Other Puritan leaders, such as the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, John Winthrop, came from the privileged class of English gentry. These well-to-do Puritans and many thousands more left their English homes not to establish a land of religious freedom, but to practice their own religion without persecution. Puritan New England offered them the opportunity to live as they believed the Bible demanded. In their “New” England, they set out to create a model of reformed Protestantism, a new English Israel. The conflict generated by Puritanism had divided English society because the Puritans demanded reforms that undermined the traditional festive culture. -

The Governors of Connecticut, 1905

ThegovernorsofConnecticut Norton CalvinFrederick I'his e dition is limited to one thousand copies of which this is No tbe A uthor Affectionately Dedicates Cbis Book Co George merriman of Bristol, Connecticut "tbe Cruest, noblest ana Best friend T €oer fia<T Copyrighted, 1 905, by Frederick Calvin Norton Printed by Dorman Lithographing Company at New Haven Governors Connecticut Biographies o f the Chief Executives of the Commonwealth that gave to the World the First Written Constitution known to History By F REDERICK CALVIN NORTON Illustrated w ith reproductions from oil paintings at the State Capitol and facsimile sig natures from official documents MDCCCCV Patron's E dition published by THE CONNECTICUT MAGAZINE Company at Hartford, Connecticut. ByV I a y of Introduction WHILE I w as living in the home of that sturdy Puritan governor, William Leete, — my native town of Guil ford, — the idea suggested itself to me that inasmuch as a collection of the biographies of the chief executives of Connecticut had never been made, the work would afford an interesting and agreeable undertaking. This was in the year 1895. 1 began the task, but before it had far progressed it offered what seemed to me insurmountable obstacles, so that for a time the collection of data concerning the early rulers of the state was entirely abandoned. A few years later the work was again resumed and carried to completion. The manuscript was requested by a magazine editor for publication and appeared serially in " The Connecticut Magazine." To R ev. Samuel Hart, D.D., president of the Connecticut Historical Society, I express my gratitude for his assistance in deciding some matters which were subject to controversy. -

THE CAPE MAY PENINSULA Is Not Like the Rest of New Jersey

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service THE CAPE MAY PENINSULA Is Not Like the Rest of New Jersey Fall migration of monarch butterflies Photographs: USFWS Unique Ecosystems Key Migratory Corridor If you have noticed something The Cape May Peninsula is well-known “different” about the Cape May as a migratory route for raptors such Peninsula, particularly in regard to as the sharp-shinned hawk (Accipiter its vegetation types, of course you striatus), osprey (Pandion haliaetus), are right! The Cape May Peninsula and northern harrier (Circus cyaneus), is not like the rest of New Jersey. The as well as owl species in great numbers. primary reason is climatic: nestled at The peninsula’s western beaches within Piping plover chick low elevation between the Atlantic Delaware Bay provide the largest Ocean and the Delaware Bay, the spawning area for horseshoe crabs peninsula enjoys approximately 225 (Limulus polyphemus) in the world frost-free days at its southern tip and, as a result, sustain a remarkable compared to 158 days at its northern portion of the second largest spring end. The vegetation, showing strong concentration of migrating shorebirds characteristics of the Pinelands flora in in North America. The increasingly the northern portion of the peninsula, rare red knot (Calidris canutus; a displays closer affinities to the mixed candidate for federal listing) as well hardwood forest of our country’s as the sanderling (C. alba), least southern Coastal Plain. Southern tree sandpiper (C. minutilla), dowitcher species such as the swamp chestnut oak (Limnodromus spp.), and ruddy (Quercus michauxii) and loblolly pine turnstone (Arenaria interpres) are (Pinus taeda) reach their northernmost some of the many bird species that distribution in Cape May County, while feed on horseshoe crab eggs to gain the common Pinelands trees such as weight for migration to their summer Swamp pink pitch pine (P. -

Medallic History of the War of 1812: Catalyst for Destruction of the American Indian Nations by Benjamin Weiss Published By

Medallic History of the War of 1812: Catalyst for Destruction of the American Indian Nations by Benjamin Weiss Published by Kunstpedia Foundation Haansberg 19 4874NJ Etten-Leur the Netherlands t. +31-(0)76-50 32 797 f. +31-(0)76-50 32 540 w. www.kunstpedia.org Text : Benjamin Weiss Design : Kunstpedia Foundation & Rifai Publication : 2013 Copyright Benjamin Weiss. Medallic History of the War of 1812: Catalyst for Destruction of the American Indian Nations by Benjamin Weiss is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://www.kunstpedia.org. “Brothers, we all belong to one family; we are all children of the Great Spirit; we walk in the same path; slake our thirst at the same spring; and now affairs of the greatest concern lead us to smoke the pipe around the same council fire!” Tecumseh, in a speech to the Osages in 1811, urging the Indian nations to unite and to forewarn them of the calamities that were to come (As told by John Dunn Hunter). Historical and commemorative medals can often be used to help illustrate the plight of a People. Such is the case with medals issued during the period of the War of 1812. As wars go, this war was fairly short and had relatively few casualties1, but it had enormous impact on the future of the countries and inhabitants of the Northern Hemisphere. At the conclusion of this conflict, the geography, destiny and social structure of the newly-formed United States of America and Canada were forever and irrevocably altered. -

Colonial Failure in the Anglo-North Atlantic World, 1570-1640 (2015)

FINDLEY JR, JAMES WALTER, Ph.D. “Went to Build Castles in the Aire:” Colonial Failure in the Anglo-North Atlantic World, 1570-1640 (2015). Directed by Dr. Phyllis Whitman Hunter. 266pp. This study examines the early phases of Anglo-North American colonization from 1570 to 1640 by employing the lenses of imagination and failure. I argue that English colonial projectors envisioned a North America that existed primarily in their minds – a place filled with marketable and profitable commodities waiting to be extracted. I historicize the imagined profitability of commodities like fish and sassafras, and use the extreme example of the unicorn to highlight and contextualize the unlimited potential that America held in the minds of early-modern projectors. My research on colonial failure encompasses the failure of not just physical colonies, but also the failure to pursue profitable commodities, and the failure to develop successful theories of colonization. After roughly seventy years of experience in America, Anglo projectors reevaluated their modus operandi by studying and drawing lessons from past colonial failure. Projectors learned slowly and marginally, and in some cases, did not seem to learn anything at all. However, the lack of learning the right lessons did not diminish the importance of this early phase of colonization. By exploring the variety, impracticability, and failure of plans for early settlement, this study investigates the persistent search for usefulness of America by Anglo colonial projectors in the face of high rate of -

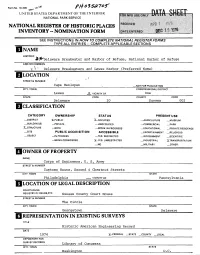

UCLA SSIFI C ATI ON

Form No. 10-300 ^ -\0-' W1 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ___________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS___________ ,NAME HISTORIC . .^ il-T^belaware Breakwater and Harbor of Refuge, National Harbor of Refuge AND/OR COMMON Y \k> Delaware Breakwaters and Lewes Harbor (Preferred Name) ________ LOCATION STREETS. NUMBER _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Lewes X VICINITY OF One STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Delaware 10 Sussex 002 UCLA SSIFI c ATI ON CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT X-PUBLIC X_OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK X_STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X-YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL -X-TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: Corps of Engineers, U. S. Army STREET & NUMBER Customs House, Second & Chestnut Streets CITY, TOWN STATE Philadelphia VICINITY OF Pennsylvania LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC. Sussex County Court House STREET & NUMBER The Circle CITY, TOWN STATE Georgetown Delaware REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Engineering Record DATE 1974 X— FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Library of Congress CITY, TOWN STATE Washington D,C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE X—EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED X_UNALTERED X-ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD _RUINS —ALTERED —MOVED DATE_______ _FAIR — UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The breakwaters at Lewes reflect three stages of construction: the two-part original breakwater, the connection between these two parts, and the outer break water.