IDEA Series: the Segregation of Students with Disabilities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to Quality Individualized Education Program (IEP) Development and Implementation

The University of the State of New York The State Education Department Guide to Quality Individualized Education Program (IEP) Development and Implementation February 2010 (Revised December 2010) THE UNIVERSITY OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK Regents of The University MERRYL H. TISCH, Chancellor, B.A., M.A., Ed.D. .................................................. New York MILTON L. COFIELD, Vice Chancellor, B.S., M.B.A., Ph.D. .................................... Rochester ROBERT M. BENNETT, Chancellor Emeritus, B.A., M.S. ........................................ Tonawanda SAUL B. COHEN, B.A., M.A., Ph.D.......................................................................... Larchmont JAMES C. DAWSON, A.A., B.A., M.S., Ph.D. .......................................................... Plattsburgh ANTHONY S. BOTTAR, B.A., J.D. ............................................................................ Syracuse GERALDINE D. CHAPEY, B.A., M.A., Ed.D. ............................................................. Belle Harbor HARRY PHILLIPS, 3rd, B.A., M.S.F.S. .................................................................... Hartsdale JOSEPH E. BOWMAN, JR., B.A., M.L.S., M.A., M.Ed., Ed.D..................................... Albany JAMES R. TALLON, JR., B.A., M.A. ......................................................................... Binghamton ROGER TILLES, B.A., J.D. ....................................................................................... Great Neck KAREN BROOKS HOPKINS, B.A., M.F.A.................................................................. -

Understanding the Use of Mobile Resources to Enhance Paralympic Boccia Teaching and Learning for Students with Cerebral Palsy

12th International Conference Mobile Learning 2016 UNDERSTANDING THE USE OF MOBILE RESOURCES TO ENHANCE PARALYMPIC BOCCIA TEACHING AND LEARNING FOR STUDENTS WITH CEREBRAL PALSY Fabiana Zioti, Giordano Clemente, Raphael de Paiva Gonçalves, Matheus Souza, Aracele Fassbinder and Ieda Mayumi Kawashita Federal Institute of Education, Science and Technology of South of Minas Gerais IFSULDEMINAS – Campus Muzambinho ABSTRACT This paper aims to discuss about how mobile technologies and resources can be used to support teaching and improving the performance of students with cerebral palsy during out-door classes in the paralympic boccia court. The Educational Design Research has been used to help us to identify the context and to build two interventions: i) using an online boccia game and ii) developing a digital booklet to support teaching and learning paralympic boccia. KEYWORDS Teaching; Disability Sports; Adapted or Paralympic boccia; Cerebral Palsy; Assistive Technology; M-Learning. 1. INTRODUCTION According to the last results from the Brazilian Population Census performed in 2010, the total Brazilian population was about 200 million inhabitants and nearly 46 million people have some form of disability. Considering this question, many teachers of the Federal Institute of Education, Science and Technology of South of Minas Gerais at Muzambinho city, in the countryside of Brazil, have been developing academic projects to promote learning and inclusion in the local community. One project aims to promote sports initiation and enhancing the full potential of students with disabilities through paralympic boccia activities in a local and formal school for adults and children with special needs. The paralympic boccia is similar to the conventional boccia, it means the player aims to touch balls in the target ball (Figure 1). -

Strategies to Include Students with Severe/Multiple Disabilities Within the General Education Classroom

Physical Disabilities: Education and Related Services, 2018, 37(2), 1-12. doi: 10.14434/pders.v37i2.24881 © Division for Physical, Health and Multiple Disabilities PDERS ISSN: 2372-451X http://scholarworks.iu.edu/journals/index.php/pders/index Article STRATEGIES TO INCLUDE STUDENTS WITH SEVERE/MULTIPLE DISABILITIES WITHIN THE GENERAL EDUCATION CLASSROOM Wendy Rogers Kutztown University Nicole Johnson Kutztown University ______________________________________________________________________________ Abstact: Federal legislation such as IDEA (1997) and NCLB (2001) have led to an increase in the number of students with significant disabilities receiving instruction in the general education classroom. This inclusionary movement has established a more diverse student population in which general and special education teachers are responsible for providing instruction that meets the needs of all their students. Although most research focuses on effective inclusionary practices for students with high incidence disabilities (e.g., learning disabilities), literature has revealed a dramatic increase in the number of students with severe/multiple disabilities receiving support in general education settings. Therefore, it is imperative that educators acquire the effective inclusive practices necessary to meet the unique needs of students with severe/multiple disabilities. A review of literature was conducted to determine effective ways to include and support students with severe/multiple disabilities within the general education classroom. Keywords: -

Report of Assessment for Special Education

Report of Assessment for Special Education Training and Technical Assistance Guide Preview Edition Table of Contents RPT 1A: RPT 1C: Student Information Student Information Validity and Reliability Assessment Conditions Reason for Assessment Strengths, Interests, Concerns Related to Area(s) of Assessment Educational Background Observations Results of Attempted General Ed. Interventions Assessment Results and Interpretation Previous or Current Special Ed. Programs Assessment Results and Interpretation(continued) Additional Educational Background Assessment Results and Interpretation(continued 2) General Medical/Health Findings Add Page Medications Add Page(continued) Vision/Hearing Family, Environmental, Cultural, Economical Factors RPT 1D: Conclusion RPT 1B: Recommendations Student Information Assistive/Augmentative Devices or Tools English Language Learners Need for Special Education and Related Services SIRAS Student Information Example English Language Learners: English Proficiency English Language Development Language of Assessment Simply click any of these titles and you will automatically be directed to the page Additional English Learner Information containing the respective information. Table of Contents Eligibility Student Information Hard of Hearing: Speech or Language Impairment: Criteria Criteria Autism: Explanation & Comments Criteria(continued) Criteria Criteria(continued 2) Criteria(continued) Intellectual Disability: Criteria(continued 3) Explanation & Comments Criteria Explanation & Comments Explanation & Comments Deaf-Blindness: -

OPERATING GUIDELINE DEAF-BLINDNESS Deaf-Blindness

OPERATING GUIDELINE DEAF-BLINDNESS Boerne ISD 130901 Legal Framework: Deaf-Blindness Category: Evaluation “Whether a child’s disability ‘adversely affects a child’s educational performance’ is considered for all disability categories in 34 CFR §300.8(c), because, to be eligible, a child must qualify as a child with a disability under 34 CFR §300.8 and need special education because of a particular impairment or condition. Although the phrase ‘adversely affects educational performance’ is not specifically defined, the extent of the impact that the child’s impairment or condition has on the child’s educational performance is a decisive factor in a child’s eligibility determination under Part B. A range of factors—both academic and nonacademic—can be considered in making this determination for each individual child. See 34 CFR §300.306(c). Even if a child is advancing from grade to grade or is placed in the regular educational environment for most or all of the school day, the group charged with making the eligibility determination still could determine that the child’s impairment or condition adversely affects the child’s educational performance because the child could not progress satisfactorily in the absence of specific instructional adaptations or supportive services, including modifications to the general education curriculum. 34 CFR §300.101(c) (regarding requirements for individual eligibility determinations for children advancing from grade to grade).” OSEP Letter to Anonymous (November 28, 2007). “Assessments or other evaluation materials must be provided and administered in the child's native language or other mode of communication and in the form most likely to yield accurate information on what the child knows and can do academically, developmentally, and functionally, unless it is clearly not feasible to do so. -

JDAIM Lesson Plans 2019

Rabbi Philip Warmflash, Chief Executive Officer Walter Ferst, President The Jewish Special Needs/Disability Inclusion Consortium of Greater Philadelphia Presents Jewish Disability Awareness & Inclusion Month (JDAIM) Lesson Plans Jewish Learning Venture innovates programs that help people live connected Jewish lives. 1 261 Old York Road, Suite 720 / Jenkintown, PA 19046 / 215.320.0360 / jewishlearningventure.org Partners with Jewish Federation of Greater Philadelphia Rabbi Philip Warmflash, Chief Executive Officer Walter Ferst, President INTRODUCTION Jewish Disability Awareness, Acceptance & Inclusion Month (JDAIM) is a unified national initiative during the month of February that aims to raise disability awareness and foster inclusion in Jewish communities worldwide. In the Philadelphia area, the Jewish Special Needs/Disability Inclusion Consortium works to expand opportunities for families of students with disabilities. The Consortium is excited to share these comprehensive lesson plans with schools, youth groups, and early childhood centers in our area. We hope that the children in our classrooms and youth groups will eventually become Jewish leaders and we hope that thinking about disability awareness and inclusion will become a natural part of their Jewish experience. We appreciate you making time for teachers to use these lessons during February—or whenever it’s convenient for you. For additional resources, please email me at gkaplan- [email protected] or call me at 215-320-0376. Thank you to Rabbi Michelle Greenfield for her hard work on this project and to Alanna Raffel for help with editing. Sincerely, Gabrielle Kaplan-Mayer, Director, Whole Community Inclusion NOTES FOR EDUCATORS · We hope that you can make these lessons as inclusive as possible for all kinds of learners and for students with different kinds of disabilities. -

SI Eligibility Guidelines for ~ Language with Autism & Language with Intellectual Disability

SI Eligibility Guidelines for ~ Language with Autism & Language with Intellectual Disability Leslie Salazar Armbruster, M.S., CCC-SLP Judy Rudebusch, EdD, CCC-SLP Host: Region 10 ESC Introduction ~ Resources Host Site: Region 10 ESC www.region10.org Moderator: Karyn Kilroy, Speech Pathology Consultant Resources available for download: SI Eligibility in Texas ~ Generic Manual SI Eligibility for Language ~ Language Manual SI Eligibility for Language with Intellectual Disability ~ Companion II Manual SI Eligibility for Language with Autism ~ Companion III Manual FAQs ~ Language with ID; Language with Autism This Power point Earning CEUs http://www.txsha.org/Online_Course_Completion.aspx 3.0 hours TSHA continuing education credit available for this training module Following the session, complete the Online Course Completion Submission Form Your name, license #, email address, phone # TSHA membership # The name and number of this course Shown on last slide of this presentation Course completion date 3-questions Learning Assessment CE evaluation of online course You will receive a certificate of course completion via email Earning CEUs http://www.txsha.org/Online_Course_Completion.aspx Access to the information is provided at no cost. TSHA Members can receive CEU credit at no cost Not a TSHA Member? $20 fee for CEU credit for this training module Complete the Online Course Completion form Mail $20 check payable to TSHA 918 Congress Ave, Suite 200, Austin, TX 78701 OR make a credit card payment on the TSHA Web site www.txsha.org -

INDIVIDUALIZED EDUCATION PROGRAM (IEP)-Annotated

IEP (ANNOTATED) Student's Name INDIVIDUALIZED EDUCATION PROGRAM (IEP) (ANNOTATED) ********************************************* School Age Student's Name: IEP Team Meeting Date: IEP Implementation Date (Projected Date When Services and Programs Will Begin): Anticipated Duration of Services and Programs: ANNOTATION: IEP Team Meeting Date: Write the date that the IEP team meeting is held. An IEP team meeting is to occur no less than once per calendar year and is conducted within 30 calendar days of a determination that the student needs special education and related services (30 calendar days following the completion of the Evaluation and Reevaluation Reports). IEP Implementation Date (Projected Date when Services and Programs Will Begin): Write the first day the student will begin to receive the supports and services described in this IEP. IEPs must be implemented as soon as possible but no later than 10 SCHOOL days after the final IEP is presented to the parent. However, when a NOREP/PWN must be issued to the parent, the LEA must wait until the 11th calendar day after presenting the NOREP/PWN to the parent. The LEA must have an IEP in effect for each student with a disability at the beginning of each school year. If the IEP annual review is due sometime in the summer, the school may not wait until the new school year to write the IEP. The IEP must be in effect at the beginning of each school year. Anticipated Duration of Services and Programs: Write the last day that the student will receive the services and programs of this IEP. This date must be one day less than a year from the team meeting date. -

Chapter 9 - Multiple Disabilities

Chapter 9 - Multiple Disabilities Definition under IDEA of Multiple Disabilities Under IDEA, Multiple Disabilities: ...means concomitant [simultaneous] impairments (such as intellectual disability-blindness, intellectual disability-orthopedic impairment, etc.), the combination of which causes such severe educational needs that they cannot be accommodated in a special education program solely for one of the impairments. The term does not include deaf-blindness [34 C.F.R., sec. 300 [b][6]]. Overview of Multiple Disabilities According to Deutsch-Smith, people with multiple disabilities require ongoing and intensive supports across their school years and typically across their lives. For some, these supports may well be in only one life activity, but for many of these individuals, supports are needed for access and participation in mainstream society. Supports are necessary because most individuals with multiple disabilities require assistance in many adaptive areas. No single definitions covers all the conditions associated with severe and multiple disabilities. Schools usually link the 2 areas (severe disabilities and multiple disabilities) into a single category for students who have the most significant cognitive, physical, or communication impairments (Turnbull, Turnbull, & Wehmeyer). Prevalence of Multiple Disabilities According to the U.S. Department of Education, Multiple Disabilities represent approximately 2.0 percent of all students having a classification in special education. Characteristics of Students with Multiple Disabilities -

Antisemitism

ANTISEMITISM ― OVERVIEW OF ANTISEMITIC INCIDENTS RECORDED IN THE EUROPEAN UNION 2009–2019 ANNUAL UPDATE ANNUAL © European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2020 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. For any use or reproduction of photos or other material that is not under the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights' copyright, permission must be sought directly from the copyright holders. Neither the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights nor any person acting on behalf of the Agency is responsible for the use that might be made of the following information. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2020 Print ISBN 978-92-9474-993-2 doi:10.2811/475402 TK-03-20-477-EN-C PDF ISBN 978-92-9474-992-5 doi:10.2811/110266 TK-03-20-477-EN-N Photo credits: Cover and Page 67: © Gérard Bottino (AdobeStock) Page 3: © boris_sh (AdobeStock) Page 12: © AndriiKoval (AdobeStock) Page 17: © Mikhail Markovskiy (AdobeStock) Page 24: © Jon Anders Wiken (AdobeStock) Page 42: © PackShot (AdobeStock) Page 50: © quasarphotos (AdobeStock) Page 58: © Igor (AdobeStock) Page 75: © Anze (AdobeStock) Page 80: © katrin100 (AdobeStock) Page 92: © Yehuda (AdobeStock) Contents INTRODUCTION � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 3 DATA COLLECTION ON ANTISEMITISM � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 4 LEGAL FRAMEWORK � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � -

Equal Protection for All Victims of Hate Crime the Case of People with Disabilities

03/2015 Equal protection for all victims of hate crime The case of people with disabilities Hate crimes violate the rights to human dignity and non-discrimination enshrined in the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union and the European Convention of Human Rights. Nevertheless, people with disabilities often face violence, discrimination and stigmatisation every day. This paper discusses the difficulties faced by people with disabilities who become victims of hate crime, and the different legal frameworks in place to protect such victims in the EU’s Member States. It ends by listing a number of suggestions for improving the situation at both the legislative and policy levels. Key facts FRA Opinions People with disabilities face discrimination, EU and national criminal law provisions stigmatisation and isolation every day, relating to hate crime should treat all which can be a formidable barrier to their grounds equally, from racism and inclusion and participation in the community xenophobia through to disability Disability is not included in the EU’s hate The EU and its Member States should crime legislation systematically collect and publish Victims of disability hate crime are often disaggregated data on hate crime, including reluctant to report their experiences hate crime against people with disabilities If incidents of disability hate crime are Law enforcement officers should be trained reported, the bias motivation is seldom and alert for indications of bias motivation recorded, making investigation and when investigating crimes prosecution less likely Trust-building measures should be undertaken to encourage reporting by disabled victims of bias-motivated or other forms of crime Equal protection for all victims of hate crime - The case of people with disabilities “[We want] to stop them being racist against us and stop some 80 million people in total. -

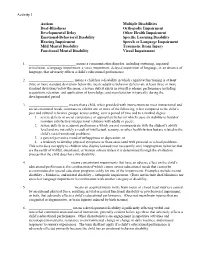

Activity 1 Autism Multiple Disabilities Deaf-Blindness Orthopedic

Activity 1 Autism Multiple Disabilities Deaf-Blindness Orthopedic Impairment Developmental Delay Other Health Impairment Emotional-Behavioral Disability Specific Learning Disability Hearing Impairment Speech or Language Impairment Mild Mental Disability Traumatic Brain Injury Functional Mental Disability Visual Impairment 1. __________________________ means a communication disorder, including stuttering, impaired articulation, a language impairment, a voice impairment, delayed acquisition of language, or an absence of language, that adversely effects a child’s educational performance. 2. _________________________ means a child has a disability in which cognitive functioning is at least three or more standard deviations below the mean; adaptive behavior deficits are at least three or more standard deviations below the mean; a severe deficit exists in overall academic performance including acquisition, retention, and application of knowledge; and manifestation is typically during the developmental period. 3. ______________________ means that a child, when provided with interventions to meet instructional and social-emotional needs, continues to exhibit one or more of the following, when compared to the child’s peer and cultural reference groups, across setting, over a period of time and to a marked degree: 1. severe deficits in social competence or appropriate behavior which cause an inability to build or maintain satisfactory interpersonal relations with adults or peers; 2. severe deficits in academic performance which are not commensurate with the student’s ability level and are not solely a result of intellectual, sensory, or other health factors but are related to the child’s social-emotional problems; 3. a general pervasive mood of unhappiness or depression; or 4. a tendency to develop physical symptoms or fears associated with personal or school problems.