Roles of Universities in Local and Regional Singapore 10

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Umbrella Agreement of ASEA-UNINET Member Universities

ir Umbrella Agreement of ASEA-UNINET Member Universities (Preamble) Recognizing the great success of the academic co-operation within ASEA-UNINET during the past 20 years and the steady progress of links between all partner institutions of the Network, Realizing the need for further measures to enhance the co-operation by means of general agreements on procedures and the facilitation of study and research programmes performed within ASEA- UNINET, and Proposing that such measures can be preferably implemented by a multilateral agreement instead of numerous bilateral agreements, (Agreement) the undersigned Universities have agreed upon the measures listed hereafter: 1. To mutually recognize academic degrees, diplomas and credits obtained from a partner university in equivalent study programmes, 2. to admit students from a partner university to study programmes on the basis of their degrees obtained at that university, in particular bachelor degrees for master studies and master degrees (2 years with thesis) for doctoral (Ph.D.) studies, provided that all conditions for admission such as availability of working space, acceptance by a supervisor and/or specific skills in fine arts are fulfilled. 3. to mutually waive tuition fees for students performing study programmes, if they have been nominated by an ASEA-UNINET member university this does not apply, however, to mandatory government taxes outside the responsibility of the university 4. to facilitate exchange of, and access to, materials within ASEA-UNINET research programmes, with agreement of non-disclosure or confidentiality if deemed necessary, 5. to provide support in identifying suitable academic supervisors, and 6. to provide support in administrative matters such as visa application, health insurance and accommodation. -

Conference Book

CONTENTS No Title Page 1. Preface 3 2. Introduction Speech 4-6 3, Welcoming Speech 1 7-8 4. Welcoming Speech 2 9-11 5. Opening Speech 12-13 6. Keynote Speech 14-16 7. List of Scientific Committee 17-29 8. List of Organizing Committee 30-33 9. ITTP-COVID19 Program Introduction 34 10. Full Program Overview 35-37 11. Program Tentative 38-39 12. List of Paper and Presentation Schedule 40-110 13. Best Paper Award Criteria 111-116 14. List of Journal and Proceeding 117-118 15. List of Partner Institutions 119 16. Sponsor 120 Contact 121 2 PREFACE It is an utmost pleasure to welcome you to the International Teleconference on Technology and Policy for Supporting Implementation of COVID-19 Response and Recovery Plan in Southeast Asia (ITTP- COVID19). ITTP-COVID19 activities consist of ASEAN leaders sharing, Scientific Paper Presentation, ASEAN Policy Group Discussion, Product Exhibition and ASEAN Tourism and Culture Exposure, which will be conducted virtually from 6th – 8th August 2021. It is organized by 27 Top Universities in Southeast Asia in collaboration with ASEAN Secretariat, ASEAN University Network, government agencies, industries and associations with the same objective of ensuring the success of COVID-19 response and recovery efforts, in the Southeast Asia region. ITTP-COVID19 provides a platform for academicians, governments, industry players, and non- governmental organizations to discuss research findings, research proposals, and experience in managing COVID-19 response and recovery plans in Southeast Asia. Ever since the start of COVID-19 outbreak in late 2019, numerous difficulties and challenges have been faced by countries around the world, including the Southeast Asia region. -

Library and Information (LIS) Research Topics in Indonesia from 2006 to 2017 Nove E

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln 2018 Library and Information (LIS) Research Topics in Indonesia from 2006 to 2017 Nove E. Variant Anna Faculty of Vocational Studies, Universitas Airlangga, [email protected] Endang Fitriyah Mannan Faculty of Vocational Studies, Universitas Airlangga, [email protected] Dyah Puspitasari Srirahayu Faculty of Vocational Studies, Universitas Airlangga Fitri Mutia Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Airlangga, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac Part of the Scholarly Communication Commons Anna, Nove E. Variant; Mannan, Endang Fitriyah; Srirahayu, Dyah Puspitasari; and Mutia, Fitri, "Library and Information (LIS) Research Topics in Indonesia from 2006 to 2017" (2018). Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). 1773. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/1773 Library and Information (LIS) Research Topics in Indonesia from 2006 to 2017 Nove E. Variant Anna [email protected] Endang Fitriyah Mannan Dyah Puspitasari Srirahayu Departemen Teknik-Faculty of Vocational Studies Universitas Airlangga – Indonesia Fitri Mutia Department of Information and Library, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences Universitas Airlangga – Indonesia ABSTRACT Library and information research (LIS) has grown significantly asmore and more library and information science programs -

Airlangga University Faculty of Pharmacy

AIRLANGGA UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF PHARMACY Kampus B UA Jl Dharmawangsa Dalam Surabaya – 60286 Phone: 031-5033710, Faks : 031-5020514 Website : http://www.ff.UA.ac.id ; E-mail: [email protected] DECISION DEAN OF FACULTY OF PHARMACY OF AIRLANGGA UNIVERSITY NUMBER: 1288/UN3.1.5/KD/2013 on: DETERMINATION OF ACADEMIC REGULATIONS ON APOTHECARY EDUCATION PROGRAM IN PHARMACY OF FACULTY OF PHARMACY OF AIRLANGGA UNIVERSITY Considering : 1. That Airlangga University aims to produce graduates with best quality, who are able to develop science, technology, humanities and art based on religious morals and be able to compete at national and international level 2. That the Faculty of Pharmacy of Airlangga University aims to produce graduates who are able and willing to integrate and develop science and technology in implementing pharmaceutical care; as innovative, creative and productive scientists with analytical and critical thinking in solving problems of pharmacy as well as professional pharmacy staff – pharmacists to improve health and quality of life in Indonesia 3. That the Faculty of Pharmacy, Airlangga University has implemented Bachelor Study Program of Pharmacy and Professional Education Program of Pharmacist, which in practice is based on the curriculum of 2012 – Faculty of Pharmacy Airlangga University 4. That some provisions in the Rector Regulation Number 11/H3/PR/2009 on the Educational Regulation of Airlangga University are needed to change to adapt to the development and dynamics of the implementation of education in Airlangga University In view of : 1. Law Number 12 of 2012, on Higher Education 2. Law Number 20 of 2003, on the National Education System 3. -

Knowledge Dissemination for Indonesian Dental Communities Through Telemedicine - a Report

International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change. www.ijicc.net Volume 15, Issue 2, 2021 Knowledge Dissemination for Indonesian Dental Communities Through Telemedicine - A Report Aqsa Sjuhada Oki1, Shuji Shimizu2, Melissa Adiatman3, Miftakhul Cahyati4, 1Faculty of Dental Medicine, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya – Indonesia, 2Telemedicine Development Center of Asia (TEMDEC), International Medical Department, Kyushu University Hospital, Fukuoka – Japan, 3Faculty of Dentistry, Universitas Indonesia, Jakarta – Indonesia, 4Faculty of Dental Medicine, University of Brawijaya, Malang – Indonesia, 1 Email: [email protected] Knowledge dissemination in dental science is a routine activity required by dentists in Indonesia. Through scientific updates, dentists can increase their capacity and lead to the health service quality improvements. To gain quality knowledge dissemination, it often takes time and cost to attend scientific meetings, so we need a breakthrough to help with this problem. Since 2016 the Faculty of Dentistry, Airlangga University, in collaboration with the Telemedicine Development Center of Asia (TEMDEC) has initiated international dental telemedicine which is performed on a regular basis, featuring both national and overseas speakers to discuss particular topics. These activities are expected to support dentists to get knowledge updates easily, as they are available in video streaming. From the questionnaires, it was concluded that the dental telemedicine program brought the benefits of knowledge dissemination to Indonesian dental communities and improved the value of the institutions involved. Key words: telemedicine, dentistry Background Dissemination of dentistry is an important requirement for dentists in Indonesia to update and improve their scientific capacity. This increased capacity is strongly correlated with an increase in the quality of dental service. -

Hong Kong Postgraduate Students' Conference on Media, 17 September 2011, Saturday

Media, Politics, Society, Culture, Business: Hong Kong Postgraduate Students' Conference on Media, 17 September 2011, Saturday. 08:30-09:00 Morning Conference Registration Panel 1 Session 1A. Asian Radio, T.V., and Movie Chair: CHU Ming Kin 09:00-10:20 Room MBG01 1. Intra-Asia Cultural Traffic: Transnational Flow of East Asian Television Dramas in Indonesia, S.M.Gietty Tambunan, Lingnan University 2. Fortune favours the ‘fair skin’ – Female actors and their success in the South Indian state of Tamil Nadu, Dhamu Pongiyannan, and The University of Adelaide. 3. Community radio in Indonesia:Development, Empowerment, and Community Diaspora. Irfan Wahyudi, Airlangga University, Indonesia. Session 1B. Hong Kong Media Chair: WANG Haiyan 9:00-10:20 Room MBG19 1. Gender Stereotypes in Hong Kong Media: Identity, Issues and Implications, Liu Yiqi, The University of Hong Kong; Bernie Mak, The Chinese University of Hong Kong 2. Amid Media Accusations of Interfering with Press Freedom: Corporate Crisis Communication through the Lens of the Press Peiyi HUANG and Lai Shan TAM, Chinese University of Hong Kong 3. The Theory of Hong Kong English Newspaper (1903-1941), Zou Yizheng, Lingnan University Coffee Break Keynote Speech: The Impact of the Internet: A Historical Perspective by James Curran Room 10:50 -12:00 MBG01 12:00-13:30 Lunch Chinese Restaurant Panel 2. 13:30 - 14:50 New Media Chair: James Curran MBG01 1. Glocal Elites: Transcultural practices as Positional Goods within Post-modernity, Daniel de Souza Malanski, IETT. Université Jean Moulin – Lyon III. 2. Social Capital and Online BBS: A Case Study, Xinyan Zhao, Purdue University 3. -

Strategy to Internationalize Universitas Airlangga

Universitas Airlangga Strategy to Internationalize Universitas Airlangga Tjitjik Srie Tjahjandarie Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya Indonesia www.unair.ac.id Vision Being an autonomous, innovative and excellent university in both national and international levels Being a pioneer in the development of science, technology, humanity and arts in the spirit of religious morality Mission To provide excellence education on academics, vocational and profesional programs To conduct innovative basic and applied research as well as research on policies to support the development of education and public services To dedicate our expertise in science and technology, humanity and arts to the community To achieve independence in conducting Tri Dharma (Education, Research, Community Service) of higher education through the development of institutionalization of management which is oriented toward quality and international competitiveness, PROFILE Universitas Airlangga Established in 1954, by First President Indonesia (Ir. Soekarno) Comprehensive University : Health Science, Life Science and Social Science Autonomous University in 2006 (7 Institution in Indonesia) Leading University in Indonesia (4 universities Indonesia rank top 200 Asia) QS University Rankings: Top 200 Asia 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 40 60 UI; 71 80 100 Rank 120 ITB; 125 UA; 127 140 UGM; 145 160 Regional and Global Webometric Ranking of South East Asia, Januari 2014 July 2013 January 2014 No. Perguruan Tinggi World SEA Rank World SEA Rank Rank Rank 1 Universitas Gadjah Mada 640 14 -

Conference Schedule

Undercurrents: Unearthing Hidden Social and Discursive Practices IACS Conference 2015 (Surabaya, 7-9 August 2015) CONFERENCE SCHEDULE Day 1 (Friday, 7 August 2015) 08.00 – 08.30 : Registration 08.30 – 10.00 : Parallel Session 1 10.00 – 11.30 : Parallel Session 2 11.30 – 13.30 : Lunch + Friday prayer 13.30 – 14.00 : Ngremo (Opening Ceremony and Cultural Performance) 14.00 – 14.30 : Opening Remarks 14.30 – 15.00 : Coffee Break 15.00 – 16.00 : Keynote Speaker (Abidin Kusno) 16.00 - 17.30 : Plenary 1 1. Hilmar Farid (Institute of Indonesian Social History, Indonesia) 2. Chua Beng Huat (NUS, Singapore) 3. Prigi Arisandi (Universitas Ciputra, Indonesia) Day 2 (Saturday, 8 August 2015) 08.30 – 10.00 : Parallel Session 3 10.00 – 10.30 : Coffee Break *Book Series Launch, Asian Cultural Studies: Transnational and Dialogic Approaches (at Room 14 (snacks/beverages are provided) 10.30 - 12.00 : Parallel Session 4 12.00 – 13.30 : Lunch 13.30 – 15.00 : Parallel Session 5 15.00 – 15.30 : Coffee Break 15.30 – 17.00 : Parallel Session 6 17.00 – 18.30 : Plenary 2 1. Diah Arimbi (Universitas Airlangga, Indonesia) 2. Firdous Azim (BRAC University, Bangladesh) 3. Goh Beng Lan (SEAS Dept. NUS, Singapore) 1 Undercurrents: Unearthing Hidden Social and Discursive Practices IACS Conference 2015 (Surabaya, 7-9 August 2015) CONFERENCE SCHEDULE Day 3 (Sunday, 9 August 2015) 08.30 – 10.00 : Parallel Session 7 10.00 – 10.30 : Coffee Break 10.30 – 12.00 : Parallel Session 8 12.00 – 13.30 : Lunch 13.30 – 15.00 : Parallel Session 9 15.00 – 16.00 : IACSS Assembly Meeting 16.00 – 16.30 : Coffee Break 16.30 – 17.00 : IACS (Reader) Book Launch 17.00 – 18.30 : Plenary 3 1. -

QS University Rankings: Asia

5th edition QS University Rankings: Asia 2013 Welcome to the 2013 University Rankings: Asia – Report he QS World University Rankings® ap- 3. POLITICAL POPULARITY Tpear to be more prophetic than other ex- However much we may hate to admit it, ercises of their type. Our rankings were the first politics plays a vital role in the development to question Harvard’s dominance at the top of and prioritisation of higher education. In the table, the first to telegraph the ascendancy the UK, higher education is stumbled into of MIT, the first to plot the rising influence of by many students, it is increasingly seen as a Singaporean and Korean institutions. The rising right rather than a privilege and the minority influence of Asian institutions can be seen in of students engaging in antisocial behaviour other studies, but nowhere more profoundly give students as a whole a bad name. Increas- than in our work. ing investment in universities would be deeply politically unpopular. By contrast, in There is a misconception that reputation Asia higher education is seen as a privilege; measures are an inherent cause of inertia in parents want nothing more than to see their rankings, that a long history is an insurmount- children attend the world’s most prestigious able advantage. It is our reputation emphasis universities and research and education are that reinforces the performance of more young amongst the most highly respected profes- institutions than any other, our reputation sions. Further investment in HE is robust measures that improve the standing of smaller policy both politically and economically. -

Prof. Satoshi Takada, Kobe University

Joint Student Programs between Japanese and Indonesian Universities at Kobe University Takada Satoshi at Yogyakarta Dean Graduate School of Health Sciences Kobe University November, 2015. International Students by Countries in Kobe University (Top 5) Country Students 1 China 686 2 Korea 95 3 Indonesia 47 4 Malaysia 34 5 Taiwan 32 1,175 international students from 78 countries/region are studying at Kobe University. Academic Exchange Agreements (Inter-university) Inter-University Exchange Agreements:6 2015. May Academic Exchange Agreements (Inter-faculty) Inter-faculty Exchange Agreements:10 Partner University Fields Bandung Institute of Technology Engineering, International Cooperation Indonesia University* Economics, International Cooperation Gadjah Mada University* Engineering, Intercultural Studies, International Cooperation Diponegoro University Medicine Indonesia University of Education International Cooperation Lampung University Agriculture Hasanuddin University Medicine Bogor Agricultural University* Medicine Andalas University Medicine Padjadjaran Nniversity Medicine * : Both Agreements in inter-university and inter-faculty levels Based on the global standard education of Kobe Univ. and Osaka Univ., in collaboration with ASEAN countries. To educate medical and health science students aiming at becoming physicians, researchers, educators and specialists. A consortium was established among Kobe Univ, Osaka Univ, Indonesia Univ, Gadjah Mada Univ, Airlangga Univ, Mahidol Univ, and Chiang Mai Univ. To foster global leaders who -

(CEIBS) Chinese University of Hong Kong Business School Fudan

5 Stars Awarded for Excellence – Asia Pacific - Astute International Influence In alphabetical order China Europe International Business School (CEIBS) Chinese University of Hong Kong Business School Fudan University School of Management HongKong University of Science and Technology HKUST Business School Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad (IIMA) Indian Institute of Management Bangalore (IIMB) Keio University Business School (KBS) Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology KAIST Business School Korea University Business School Monash University Faculty of Business and Economics Nanyang Technological University Business School National Taiwan University College of Management National University of Singapore NUS Business School Peking University Guanghua School of Management Seoul National University SNU Business School Shanghai Jiao Tong University Antai College of Economics and Management Tsinghua University School of Economics and Management University of Auckland Business School University of Hong Kong Faculty of Business and Economics University of Melbourne Business School University of New South Wales University of Sydney Business School Waseda University Graduate School of Economics and Business Yongsei University School of Business 4 Stars Awarded for Excellence – Asia Pacific - Significant International Influence In alphabetical order Almaty Management University Asian Institute of Management (AIM) Asian Institute of Technology Auckland University of Technology Business School Australian National University College -

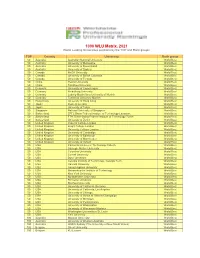

WLU Table 2021

1000 WLU Matrix. 2021 World Leading Universities positions by the TOP and Rank groups TOP Country University Rank group 50 Australia Australian National University World Best 50 Australia University of Melbourne World Best 50 Australia University of Queensland World Best 50 Australia University of Sydney World Best 50 Canada McGill University World Best 50 Canada University of British Columbia World Best 50 Canada University of Toronto World Best 50 China Peking University World Best 50 China Tsinghua University World Best 50 Denmark University of Copenhagen World Best 50 Germany Heidelberg University World Best 50 Germany Ludwig-Maximilians University of Munich World Best 50 Germany Technical University Munich World Best 50 Hong Kong University of Hong Kong World Best 50 Japan Kyoto University World Best 50 Japan University of Tokyo World Best 50 Singapore National University of Singapore World Best 50 Switzerland EPFL Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne World Best 50 Switzerland ETH Zürich-Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich World Best 50 Switzerland University of Zurich World Best 50 United Kingdom Imperial College London World Best 50 United Kingdom King's College London World Best 50 United Kingdom University College London World Best 50 United Kingdom University of Cambridge World Best 50 United Kingdom University of Edinburgh World Best 50 United Kingdom University of Manchester World Best 50 United Kingdom University of Oxford World Best 50 USA California Institute of Technology Caltech World Best 50 USA Carnegie