Download Recommender's Annotations (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Fragile Legacy of Amphicoelias Fragillimus (Dinosauria: Sauropoda; Morrison Formation – Latest Jurassic)

Volumina Jurassica, 2014, Xii (2): 211–220 DOI: 10.5604/17313708 .1130144 The fragile legacy of Amphicoelias fragillimus (Dinosauria: Sauropoda; Morrison Formation – latest Jurassic) D. Cary WOODRUFF1,2, John R. FOSTER3 Key words: Amphicoelias fragillimus, E.D. Cope, sauropod, gigantism. Abstract. In the summer of 1878, American paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope published the discovery of a sauropod dinosaur that he named Amphicoelias fragillimus. What distinguishes A. fragillimus in the annals of paleontology is the immense magnitude of the skeletal material. The single incomplete dorsal vertebra as reported by Cope was a meter and a half in height, which when fully reconstructed, would make A. fragillimus the largest vertebrate ever. After this initial description Cope never mentioned A. fragillimus in any of his sci- entific works for the remainder of his life. More than four decades after its description, a scientific survey at the American Museum of Natural History dedicated to the sauropods collected by Cope failed to locate the remains or whereabouts of A. fragillimus. For nearly a cen- tury the remains have yet to resurface. The enormous size of the specimen has generally been accepted despite being well beyond the size of even the largest sauropods known from verifiable fossil material (e.g. Argentinosaurus). By deciphering the ontogenetic change of Diplodocoidea vertebrae, the science of gigantism, and Cope’s own mannerisms, we conclude that the reported size of A. fragillimus is most likely an extreme over-estimation. INTRODUCTION saurs pale in comparative size; thus A. fragillimus could be the largest dinosaur, and largest vertebrate in Earth’s history Described by Edward Drinker Cope in 1878, the holo- (the Blue Whale being approximately 29 meters long [Reilly type (and only) specimen of A. -

Biomechanical Reconstruction of the Appendicular Skeleton in Three

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Biomechanical reconstruction of the appendicular skeleton in three North American Jurassic sauropods Ray Wilhite Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Earth Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Wilhite, Ray, "Biomechanical reconstruction of the appendicular skeleton in three North American Jurassic sauropods" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2677. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2677 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. BIOMECHANICAL RECONSTRUCTION OF THE APPENDICULAR SKELETON IN THREE NORTH AMERICAN JURASSIC SAUROPODS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Geology an Geophysics by Ray Wilhite B.S., University of Alabama at Birmingham, 1995 M.S., Brigham Young University, 1999 May 2003 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the Jurassic Foundation, the LSU chapter of Sigma Xi, and the LSU Museum of Natural Science for their support of this project. I am also grateful to Art Andersen of Virtual Surfaces for the use of the Microscribe digitizer as well as for editing of data for the project. I would like to thank Ruth Elsey of the Rockefeller Wildlife Refuge for supplying all the Alligator specimens dissected for this paper. -

Fall/Winter 2016

InsIde: digging Up dinosaurs The member magazine of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University Fall 2016 Academy Greetings President and CEO: George W. Gephart, Jr. Director of Membership and Appeals: Lindsay A. Fiesthumel Director of Communications: Mary Alice Hartsock Senior Graphic Designer: Stephanie Gleit Contributing Writers: Jason Poole, Mike Servedio, Jennifer Vess Academy Frontiers is a publication of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, 1900 Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia, PA 19103. Please send questions or comments about Academy Frontiers to [email protected]. Academy membership includes a subscription to Academy Frontiers, free general admission to the museum, discounts in the Academy Shop and Academy Café, invitations to special events and Katie Clark/ANS Katie exhibit openings, and much more. Dear Friends, For information about Academy membership, call 215-299-1022 or visit ansp.org/membership. The Academy is the place in Philadelphia to see and learn about fossils, thanks to exciting Board of Trustees current exhibits such as Dinosaurs Unearthed and our famous Dinosaur Hall. Did you Chair of the Board know that paleontology is embedded deeply in our rich history and current scientific Peter A. Austen research? Among our many famous personalities was Academy scientist and father of Trustees American vertebrate paleontology Joseph Leidy, who identified the extinct American John F. Bales III lion and named the famous dinosaur Hadrosaurus foulkii after its discovery in 1858 in Jeffrey Beachell Haddonfield, New Jersey. The Academy created a full cast of the dinosaur and put it on M. Brian Blake display in 1868, becoming the first place in the world where the public could go to see a Amy Branch Amy Coes dinosaur. -

Why Sauropods Had Long Necks; and Why Giraffes Have Short Necks

TAYLOR AND WEDEL – LONG NECKS OF SAUROPOD DINOSAURS 1 of 39 Why sauropods had long necks; and why giraffes have short necks Michael P. Taylor, Department of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol BS8 1RJ, England. [email protected] Mathew J. Wedel, College of Osteopathic Medicine of the Pacific and College of Podiatric Medicine, Western University of Health Sciences, 309 E. Second Street, Pomona, California 91766-1854, USA. [email protected] Table of Contents Abstract............................................................................................................................................2 Introduction......................................................................................................................................3 Museum Abbreviations...............................................................................................................3 Long Necks in Different Taxa..........................................................................................................3 Extant Animals............................................................................................................................4 Extinct Mammals........................................................................................................................4 Theropods....................................................................................................................................5 Pterosaurs....................................................................................................................................6 -

Description of Unusual Pathological Disorders on Pubes and Associated Left Femur from a Diplodocus Specimen

Paludicola 11(4):179-187 April 2018 © by the Rochester Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology DESCRIPTION OF UNUSUAL PATHOLOGICAL DISORDERS ON PUBES AND ASSOCIATED LEFT FEMUR FROM A DIPLODOCUS SPECIMEN Ryan J. Clayton Nottingham, UK. <[email protected]> ABSTRACT The main hypothesis of this study is that a Diplodocus was injured, resulting in a variety of paleopathologies described herein. Several bones have unusual pathologies, such as a left pubis bone with an abnormal growth and a left femur with an extended fourth trochanter. Pathologies present in these bones suggest an injury from an unknown cause, which the Diplodocus survived. The left pubis bone growth shows signs of possibly being purulent, and the right pubis shows evidence of healing after fracturing due to the presence of a callus. Osteomyelitis may have occurred in a growth from a pubis and enthesitis on the left femur, causing an extension to the fourth trochanter on the left femur from muscle strain. The extension of the fourth trochanter on the left femur suggests that the m. caudofemoralis longus on the left femur was also damaged by the injury, and the healing process involved fibrous entheseal changes to strengthen the muscle attachment site. It remains unknown if it was damaged in the same impact injury or from a different, unrelated scenario. INTRODUCTION which is a disorder between ligament attachments to bone, causing inflammation at sites where tendons Studies in paleopathologies of dinosaurs allow the connect to bone (McGonagle et al., 1998). opportunity to study the behavior of these extinct Enthesophytes are calcifications of tendon attachments. animals (Rothschild and Tanke, 1991; Waldron, 2009). -

Central Chapter 18: Wyoming

Nationwide Public Safety Broadband Network Final Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement for the Central United States VOLUME 16 - CHAPTER 18 Montana North Dakota Minnesota Colorado Illinois Wisconsin South Dakota Indiana Wyoming Michigan Iowa Iowa Kansas Nebraska Michigan Ohio Utah Illinois Indiana Minnesota Colorado Missouri Kansas Missouri Montana Nebraska North Dakota Ohio South Dakota Utah Wisconsin Wyoming JUNE 2017 First Responder Network Authority Nationwide Public Safety Broadband Network Final Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement for the Central United States VOLUME 16 - CHAPTER 18 Amanda Goebel Pereira, AICP NEPA Coordinator First Responder Network Authority U.S. Department of Commerce 12201 Sunrise Valley Dr. M/S 243 Reston, VA 20192 Cooperating Agencies Federal Communications Commission General Services Administration U.S. Department of Agriculture—Rural Utilities Service U.S. Department of Agriculture—U.S. Forest Service U.S. Department of Agriculture—Natural Resource Conservation Service U.S. Department of Commerce—National Telecommunications and Information Administration U.S. Department of Defense—Department of the Air Force U.S. Department of Energy U.S. Department of Homeland Security June 2017 Page Intentionally Left Blank. Final Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement Chapter 18 FirstNet Nationwide Public Safety Broadband Network Wyoming Contents 18. Wyoming ............................................................................................................................. 18-7 18.1. Affected -

Scavenger Hunt High School

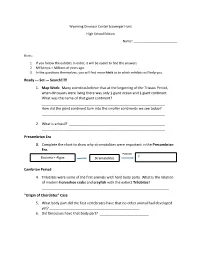

Wyoming Dinosaur Center Scavenger Hunt: High School Edition Hints: 1. If you follow the exhibits in order, it will be easier to find the answers. 2. MYA/mya = millions of years ago. 3. In the questions themselves, you will find more hints as to which exhibits will help you. Ready—Set—Search! 1. Draw and label the four layers of the Earth with thicknesses of each layer. Word bank: inner core, crust, outer core, mantle 2. Name 2 scientists who helped develop the theory of plate tectonics and briefly define their contributions. ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ Precambrian Era 3. Complete the chart to show why stromatolites were important in the Precambrian. Bacteria + Algae Stromatolites Cambrian Period 4. Trilobites were some of the first animals with hard body parts What is the family of organisms containing modern horseshoe crabs, crayfish and the extinct Trilobite? _____________________________________ Mollusca 5. Find the “heteromorph” ammonites. What do you think might be a possible reason for these odd shapes? ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ Plants 6. When did Algae first appear?________________________________________________ -

Ready --- Set --- Search!!!!! 1. Map Work: Many Scientists Believe That

Wyoming Dinosaur Center Scavenger Hunt High School Edition Name: ________________________ Hints: 1. If you follow the exhibits in order, it will be easier to find the answers. 2. MYA/mya = Millions of years ago. 3. In the questions themselves, you will find more hints as to which exhibits will help you. Ready --- Set --- Search!!!!! 1. Map Work: Many scientists believe that at the beginning of the Triassic Period, when dinosaurs were living there was only 1 giant ocean and 1 giant continent. What was the name of that giant continent? _______________________________________________________________ How did the giant continent turn into the smaller continents we see today? _______________________________________________________________ 2. What is a fossil? _________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ Precambrian Era 3. Complete the chart to show why stromatolites were important in the Precambrian Era. Produced Bacteria + Algae ? Stramatolites Cambrian Period 4. Trilobites were some of the first animals with hard body parts. What is the relation of modern horseshoe crabs and crayfish with the extinct Trilobites? _________________________________________________________________ “Origin of Chordates” Case 5. What body part did the first vertebrates have that no other animal had developed yet? ______________________________________________ 6. Did Dinosaurs have that body part? _________________________ Placoderms 7. Many fish developed during this time. These early fish of -

Dino Foot Race

Dino Foot Race Childhood Learning Objective Language Development: Listening and understanding, speaking and communicating Literacy: Phonological awareness Science: Scientific knowledge Math: Solving problems Creative Arts: Art Social and Emotional Development: Self-concept, self-control, cooperation Approaches to Learning: Initiative and curiosity Physical Health and Development: Fine motor skills ______________________________________________________________________________ Learning Goals/Objectives Understand the difference between how fast dinosaurs could run Understand that all living things are categorized Understand how paleontologists name dinosaurs ______________________________________________________________________________ Background Information There are different types of paleo-environments that paleontologists work in. From dry deserts to wet marshlands, paleontologists uncover fossils from various time periods and see evidence of their environments in the geologic record. In these fossil records, are where paleontologists find dinosaurs and other fossils. Paleontologists use different methods of science and math to understand dinosaur behavior. One of these behaviors is movement. Many people may wonder how fast a dinosaur could run and this can be solved based on the fossil record. This activity will show the student how we can calculate the speed of various dinosaurs. ______________________________________________________________________________ Whole Group Classroom Activity Materials: • Dino Foot Race Activity Sheet -

Thermopolis Hot Springs

Thermopolis Hot Springs FREE Visitor Guide • Hot Springs State Park • Gift of the Waters Pageant • Wyoming Dinosaur Center • Cowboy Rendezvous PRCA Rodeo • Legend Rock Petroglyphs • Hot Springs County Museum • W ind River Canyon Scenic Byway • Boysen State Park 2 Thermopolis Hot Springs Visitor Guide Real Cowboy Gear Since ‘97 Two Great Stores - One Location Check us out on Facebook 180 Hwy 20 South • Thermopolis, WY 82443 307-864-3047 • Toll Free 1-877-864-3048 [email protected] • Open Monday - Saturday • Closed Sunday WelcomeWelcome Travelers!Travelers! • Year round mineral spa/seasonal Best Western Plus freshwater pool • Free deluxe Plaza Hotel continental breakfast • Free high-speed Hot Springs State Park 100% wireless internet Thermopolis, WY • HD DirecTV Smoke Free • 18 Suites Phone: 800-780-7234 & Pet Free • Newly remodeled bathrooms 307-864-2939 email: [email protected] www.bestwestern.com Thermopolis Hot Springs Visitor Guide 3 Wind River Canyon Whitewater & Flyfishing Thrills & Scenery You’ll Never Forget... Open 7 days a week Memorial day to Labor day Guided Fly-fishing trips available in wind River Canyon & on Big Horn River year round (weather permitting) wind River Reservation and state of wyoming Fishing permits The canyon, named after the Wind River, lies north of Boysen Reservoir and is located on part of the Wind River Indian Reservation (home of the Shoshone and Northern Arapaho Tribes). WhiteWater trips: •2 Hour Trips pete and Darren Calhoun 210 Hwy. 20 South, Ste. #5 •5-6 Hour Trip with BBQ Thermopolis, WY -

Jurassic Fishbowl

Jurassic Fishbowl Early Childhood Learning Objective Language Development: Listening and understanding, speaking and communicating Literacy: Phonological awareness Science: Scientific knowledge Creative Arts: Art Social and Emotional Development: Self-concept, self-control, cooperation Approaches to Learning: Initiative and curiosity Physical Health and Development: Fine motor skills ______________________________________________________________________________ Learning Goals/Objectives Understand that different animals lived in different environments Understand the difference between dinosaurs and marine reptiles Understand the difference between vertebrates and invertebrates ______________________________________________________________________________ Background Information There are different types of paleo-environments that paleontologists work in. From dry deserts to wet marshlands, paleontologists uncover fossils from various time periods and see evidence of their environments in the geologic record. Paleontology is not just the study of dinosaurs. The world has more marine deposits than terrestrial. Marine fossils are found on every continent in the world, and we have a better understanding of these animals than most anything else due to the abundance of these fossils. ______________________________________________________________________________ Whole Group Classroom Activity Materials: • Jurassic Fishbowl Sheet • Crayons • Markers • Construction Paper • Scissors • Glue Preparation: 1. Print out Jurassic Fishbowl sheets, one -

Dinosaur Experience Most Primitive to the Origins of the Dominant Land Prehistoric Experience Like No Other

Our Story VISIT US Established in 1995, The Wyoming Dinosaur Center Your Jurassic Journey begins at The Wyoming is home to an unparalleled fossil collection from Our Museum Dinosaur Center and Dig Sites. Located in the Big around the world and amazing fossil discoveries Horn Basin of central Wyoming, we are adjacent The World’s Greatest from Wyoming. As one of the world’s top ten The Walk Through Time presents fossils from across to the breathtaking Wind River Canyon and a short dinosaur museums, visitors gain an interactive the world. Visitors follow the evolution of life from the road trip away from these destinations: Dinosaur Experience most primitive to the origins of the dominant land prehistoric experience like no other. EXPLORE • DISCOVER • EXCAVATE group of the Mesozoic Era, the dinosaurs. • 2.5 hours to Yellowstone National Park The Wyoming Dinosaur Center (WDC) is a 501(c)3 • 3.5 hours to Jackson Hole and Teton National Park non-profit organization devoted to the advancement In the Hall of Dinosaurs lies ... • 4 hours to Devil’s Tower of paleontological education, outreach and research. • 2 hours to Casper We work to provide outstanding hands-on geologic “The Thermopolis Specimen” • 1.5 hours to Cody and paleontological experiences that are engaging The most complete and well-preserved Archaeopteryx and enjoyable for visitors of all ages. found and the only specimen on display in North America. “Jimbo” Open 7 days a week - all year! The second Supersaurus specimen ever discovered and the largest dinosaur found in Wyoming. At 106 feet Summer Season 8 AM-6 PM long, he is one of the longest dinosaurs to have lived.