Law Enforcement by Stereotypes and Serendipity: Racial Profiling and Stops and Searches Without Cause

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fundraising-TD Jakes- John Rewrite

Who Wants to Be Among the First to Experience The Bible in a Radically Different Way? Connect with God and Understand YOUR Role in His Plan with the “The Bible Experience” My Gift to YOU This Christmas Season Dear________ Now, don’t be concerned that you will need to READ the entire New Testament in order to be positioned for this miracle blessing. You do not READ this amazing new version of Scripture, you LISTEN to it! I have been extremely privileged to be called upon and appointed by Zondervan Publishers, the largest publishers of the Bible in the world, to be the voice of the Holy Spirit in a new multimedia presentation of the Bible called, “The Bible Experience!” I am joined by over 100 other African-Americans in producing this dramatic re-enactment of the Scriptures in the Bible: Blair Underwood, Angela Bassett, Cuba Gooding Jr., Samuel L. Jackson, Yolanda Adams, LeVar Burton, and Tisha Campbell Martin just to name a few! While we were in production on this masterful new version of the Bible, I had a private moment with Levar Burton… This is what he told me: “My work on this Bible Experience project is among the most gratifying in my career. I feel so Blessed to be a part of this and share God’s Word in a way that will change families. “ “The Bible Experience” is in today’s contemporary language, using the New International Version of the Bible. It comes in an amazing CD set and has just been released by Zondervan. Many expect it to top the charts and provide an even greater blessing to millions the world over. -

John Doyle Insurancedoyle Insurance AGENCY

FINAL-2 Sat, Jun 30, 2018 8:14:39 PM Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment for the week of July 7 - 13, 2018 OLD FASHIONED SERVICE FREE REGISTRY SERVICE John Doyle INSURANCEDoyle Insurance AGENCY Voted #1 1 x 3 Insurance Agency When a big city crime reporter (Amy Adams, “Arrival,” 2016) returns to her hometown Home sweet home to cover a string of gruesome killings, not all is what it seems. Jean-Marc Vallée (“Dal- las Buyers Club,” 2013) reunites with HBO to helm another beloved novel adaptation Auto • Homeowners in Gillian Flynn’s “Sharp Objects,” premiering Sunday, July 8, on HBO. The ensemble Business • Life Insurance cast also includes Patricia Clarkson (“House of Cards”) and Chris Messina (“The Mindy Patricia Clarkson stars in “Sharp Objects” 978-777-6344 Project”). www.doyleinsurance.com FINAL-2 Sat, Jun 30, 2018 8:14:41 PM 2•SalemNews•July 7 - 13, 2018 Into the fire: A crime reporter is drawn home in ‘Sharp Objects’ By Francis Babin by Patricia Clarkson (“House of ten than not, alone. The boozy try to replicate its success by fol- discussed this at the ATX Television TV Media Cards”). nights help with her ever-growing lowing the same formula: a trendy, Festival in Austin, Texas, explaining Video Three preteen victims and a po- sense of paranoia but trigger pain- well-known novel, big name talent that “Camille needed to be ex- releases n recent years, we’ve seen a real tential serial killer on the loose is a ful recollections of her sister Mari- and a celebrated auteur/director in plored over eight episodes. -

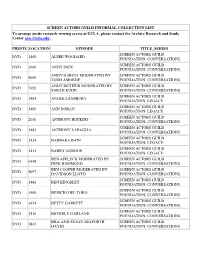

SCREEN ACTORS GUILD INFORMAL COLLECTION LIST to Arrange Onsite Research Viewing Access at UCLA, Please Contact the Archive Research and Study Center [email protected]

SCREEN ACTORS GUILD INFORMAL COLLECTION LIST To arrange onsite research viewing access at UCLA, please contact the Archive Research and Study Center [email protected] . PREFIX LOCATION EPISODE TITLE_SERIES SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1460 ALFRE WOODARD FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1669 ANDY DICK FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS ANDY GARCIA MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 8699 TODD AMORDE FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS ANDY RICHTER MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 7020 SARAH KUHN FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1484 ANGLE LANSBURY FOUNDATION: LEGACY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1409 ANN DORAN FOUNDATION: LEGACY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 2010 ANTHONY HOPKINS FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1483 ANTHONY LAPAGLIA FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1434 BARBARA BAIN FOUNDATION: LEGACY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1413 BARRY GORDON FOUNDATION: LEGACY BEN AFFLECK MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 6348 PETE HAMMOND FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS BEN COOPER MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 8697 DAVIDSON LLOYD FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1486 BEN KINGSLEY FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1500 BENICIO DEL TORO FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1674 BETTY GARRETT FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1416 BEVERLY GARLAND FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS BILL AND SUSAN SEAFORTH SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1843 HAYES FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS BILL PAXTON MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 7019 JENELLE RILEY FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS -

2012 Annual Report

2012 ANNUAL REPORT Table of Contents Letter from the President & CEO ......................................................................................................................5 About The Paley Center for Media ................................................................................................................... 7 Board Lists Board of Trustees ........................................................................................................................................8 Los Angeles Board of Governors ................................................................................................................ 10 Public Programs Media As Community Events ......................................................................................................................14 INSIDEMEDIA/ONSTAGE Events ................................................................................................................15 PALEYDOCFEST ......................................................................................................................................20 PALEYFEST: Fall TV Preview Parties ...........................................................................................................21 PALEYFEST: William S. Paley Television Festival ......................................................................................... 22 Special Screenings .................................................................................................................................... 23 Robert M. -

External Content.Pdf

i THE THEATRE OF TENNESSEE WILLIAMS Brenda Murphy is Board of Trustees Distinguished Professor of English, Emeritus at the University of Connecticut. Among her 18 books on American drama and theatre are Tennessee Williams and Elia Kazan: A Collaboration in the Theatre (1992), Understanding David Mamet (2011), Congressional Theatre: Dramatizing McCarthyism on Stage, Film, and Television (1999), The Provincetown Players and the Culture of Modernity (2005), and as editor, Critical Insights: Tennessee Williams (2011) and Critical Insights: A Streetcar Named Desire (2010). In the same series from Bloomsbury Methuen Drama: THE PLAYS OF SAMUEL BECKETT by Katherine Weiss THE THEATRE OF MARTIN CRIMP (SECOND EDITION) by Aleks Sierz THE THEATRE OF BRIAN FRIEL by Christopher Murray THE THEATRE OF DAVID GREIG by Clare Wallace THE THEATRE AND FILMS OF MARTIN MCDONAGH by Patrick Lonergan MODERN ASIAN THEATRE AND PERFORMANCE 1900–2000 Kevin J. Wetmore and Siyuan Liu THE THEATRE OF SEAN O’CASEY by James Moran THE THEATRE OF HAROLD PINTER by Mark Taylor-Batty THE THEATRE OF TIMBERLAKE WERTENBAKER by Sophie Bush Forthcoming: THE THEATRE OF CARYL CHURCHILL by R. Darren Gobert THE THEATRE OF TENNESSEE WILLIAMS Brenda Murphy Series Editors: Patrick Lonergan and Erin Hurley LONDON • NEW DELHI • NEW YORK • SYDNEY Bloomsbury Methuen Drama An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com Bloomsbury is a registered trademark of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2014 © Brenda Murphy, 2014 This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Licence. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher. -

Layout 1 (Page 2)

ACTION THRILLER DRAMA KIDS COMEDY HORROR MARTIAL ARTS SPECIAL INTEREST DVD CATALOG TABLE OF CONTENTS FAMILY 3-4 ANIMATED 4-5 KID’S SOCCER 5 COMEDY 6 STAND-UP COMEDY 6 COMEDY TV DVD 7 DRAMA 8-11 TRUE STORIES COLLECTION 12-14 THRILLER 15-16 HORROR 16 ACTION 16 MARTIAL ARTS 17 EROTIC 17-18 DOCUMENTARY 18 MUSIC 18 NATURE 18-19 INFINITY ROYALS 20 INFINITY ARTHOUSE 20 INFINITY AUTHORS 21 DISPLAYS 22 TITLE INDEX 23-24 Josh Kirby: Trapped on Micro-Mini Kids Toyworld Now one inch tall, Josh Campbell has his Fairy Tale Police Department The lifelike toy creations of a fuddy-duddy work cut out, but being tiny has its perks. (FTPD) tinkerer rally to Josh's cause. Stars CORBIN Stars COLIN BAIN AND JOSH HAMMOND There’s trouble in Fairy Tale Land! For some reason, the ALLRED, JENNIFER BURNES AND DEREK 90 Minutes / Not Rated world’s best known fairy tales aren’t ending the way they WEBSTER Johnny Mysto Cat: DH9013 / UPC: 844628090131 should. So it’s up to the team at the Fairy Tale Police Department to put An enchanted ring transports a young 91 Minutes / Rated PG the Fairy Tales back on track, and assure they end they way they’re magician back to thrilling adventures in Cat: DH9081 / UPC: 844628090810 supposed to... Happily Ever After! Ancient Britain. Stars TORAN CAUDELL, FTPD: Case File 1 AMBER TAMBLYN AND PATRICK RENNA PINOCCHO, THE THREE LITTLE PIGS, 87 Minutes / Rated PG SNOW WHITE & THE SEVEN DWARFS, THE Cat: DH9008 / UPC: 844628090087 FROG PRINCE, SLEEPING BEAUTY 120 Minutes / Not Rated Cat: TE1069 / UPC: 844628010696 Josh Kirby: Human Pets Kids Of The Round Table Josh and his pals have timewarped to For Alex, Excalibur is just a legend, that is 70,379 and the Fatlings are holding them until he tumbles into a magic glade where hostage! Stars CORBIN ALLRED, JENNIFER the famed sword and Merlin the Magician BURNS AND DEREK WEBSTER appear. -

Journalism 375/Communication 372 the Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture

JOURNALISM 375/COMMUNICATION 372 THE IMAGE OF THE JOURNALIST IN POPULAR CULTURE Journalism 375/Communication 372 Four Units – Tuesday-Thursday – 3:30 to 6 p.m. THH 301 – 47080R – Fall, 2000 JOUR 375/COMM 372 SYLLABUS – 2-2-2 © Joe Saltzman, 2000 JOURNALISM 375/COMMUNICATION 372 SYLLABUS THE IMAGE OF THE JOURNALIST IN POPULAR CULTURE Fall, 2000 – Tuesday-Thursday – 3:30 to 6 p.m. – THH 301 When did the men and women working for this nation’s media turn from good guys to bad guys in the eyes of the American public? When did the rascals of “The Front Page” turn into the scoundrels of “Absence of Malice”? Why did reporters stop being heroes played by Clark Gable, Bette Davis and Cary Grant and become bit actors playing rogues dogging at the heels of Bruce Willis and Goldie Hawn? It all happened in the dark as people watched movies and sat at home listening to radio and watching television. “The Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture” explores the continuing, evolving relationship between the American people and their media. It investigates the conflicting images of reporters in movies and television and demonstrates, decade by decade, their impact on the American public’s perception of newsgatherers in the 20th century. The class shows how it happened first on the big screen, then on the small screens in homes across the country. The class investigates the image of the cinematic newsgatherer from silent films to the 1990s, from Hildy Johnson of “The Front Page” and Charles Foster Kane of “Citizen Kane” to Jane Craig in “Broadcast News.” The reporter as the perfect movie hero. -

Little Oscar's Big Night

M a r c h 2 , 2 0 0 6 Music,M u s i c , MoviesM o v i e s aandn d MMoreo r e LITTLE OSCAR’S BIG NIGHT 15 Minutes With An Artist Madea Proves Love Heals Broken Hearts Entertainment News, Fashion Trends, Music Reviews and More ... M A R C H 2 , 2 0 0 6 INSIDE [email protected] 2 THE BUZZ time of the arrest; he is currently to Jessica Simpson’s soon-to-be out on bail … Mariah Carey is ex, Nick Lachey), Drew Lachey INSIDE also back - in the movies that is. and his partner, professional CONTENTS The 35-year-old singer is going to dancer, Cheryl Burke took home star in an independent movie titled the prize in “Dancing With the 02 Entertainment News “Tennessee.” After her disastrous Stars” last weekend, which aired movie “Glitter” tanked in 2001, on ABC … New CD releases of Top 10 iPod Downloads By Mahsa Khalilifar the famed songstress doesn’t seem the week include Country star Daily Titan Columnist like a good choice for the part, Alan Jackson’s Precious Moments 03 Flashback Favoritevorite but the producer said he is confi- … R&B newcomer Ne-Yo’s In dent in his decision, according to My Own Words … rock’s bad 04 Special Feature - CBGB’s It is hard to forget a face in People … Don Knotts a.k.a. the boy Kid Rock’s Live Trucker… Hollywood when it becomes lovable Mr. Furley from “Three’s singer Andrea Bocelli’s Amor… 05 Spotlight: Th e Oscars notorious or infamous for one Company” died last week at the New DVD releases include Keira reason or another … one per- age of 81 … Cancer survivor, Knightley, who stars in yet anoth- 06 Madea Proves Love Heals son who knows this all too well Tour de France winner and for- er one out this week: “Pride and is George Michael. -

Celebrate Black History Month

Celebrate The ABC’s of Black History Month A is for Angelou The wit, wisdom, and power of Maya Angelou's work have made her one of the most beloved contemporary American writers. Her writings have brought her numerous awards, and she has been nominated for a Tony, an Emmy, and a Pulitzer prize. B is for Beckwourth In 1850, James Beckwourth found a passageway through the Sierra Nevada mountain range near Reno Nevada which helped future settlers to reach California. That pass is called Beckwourth Pass. Ex-Slave and Early Pioneer Western Frontiersman C is for Chisholm Shirley Chisholm, the first black woman elected to Congress and an outspoken advocate for women and minorities during seven terms in the House “Service is the rent we pay for the privilege of living on this earth.” D is for Drew Charles R. Drew was a renowned surgeon, teacher, and researcher. He was responsible for founding two of the world's largest blood banks. Renowned Surgeon and Blood researcher E is for Ellington The man who made "Take the 'A' Train" his signature song was none other than the musical giant Edward Kennedy Ellington, better known as Duke Ellington. Ellington (1899-1974) was born in Washington, D.C., and by the time he was 15, he was composing. F is for Fitzgerald Discovered as a teenager at the Apollo Theatre in Harlem, Ella Fitzgerald and her swing style of vocal jazz transcend the times. Recognized as the best female jazz vocalist of the century as well as a pioneer in the area of jazz, Fitzgerald was respected worldwide by musicians and audiences alike. -

A Critical Analysis of the Black President in Film and Television

“WELL, IT IS BECAUSE HE’S BLACK”: A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE BLACK PRESIDENT IN FILM AND TELEVISION Phillip Lamarr Cunningham A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2011 Committee: Dr. Angela M. Nelson, Advisor Dr. Ashutosh Sohoni Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Michael Butterworth Dr. Susana Peña Dr. Maisha Wester © 2011 Phillip Lamarr Cunningham All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Ph.D., Advisor With the election of the United States’ first black president Barack Obama, scholars have begun to examine the myriad of ways Obama has been represented in popular culture. However, before Obama’s election, a black American president had already appeared in popular culture, especially in comedic and sci-fi/disaster films and television series. Thus far, scholars have tread lightly on fictional black presidents in popular culture; however, those who have tend to suggest that these presidents—and the apparent unimportance of their race in these films—are evidence of the post-racial nature of these texts. However, this dissertation argues the contrary. This study’s contention is that, though the black president appears in films and televisions series in which his presidency is presented as evidence of a post-racial America, he actually fails to transcend race. Instead, these black cinematic presidents reaffirm race’s primacy in American culture through consistent portrayals and continued involvement in comedies and disasters. In order to support these assertions, this study first constructs a critical history of the fears of a black presidency, tracing those fears from this nation’s formative years to the present. -

Production in Ontario 2019

SHOT IN ONTARIO 2019 Feature Films – Theatrical A GRAND ROMANTIC GESTURE Feature Films – Theatrical Paragraph Pictures Producers: David Gordian, Alan Latham Exec. Producer: n/a Director: Joan Carr-Wiggin Production Manager: Mary Petryshyn D.O.P.: Bruce Worrall Key Cast: Gina McKee, Douglas Hodge, Linda Kash, Rob Stewart, Rose Reynolds, Dylan Llewellyn Shooting dates: Jun 24 - Jul 19/19 AGAINST THE WILD III – THE JOURNEY HOME Feature Films – Theatrical Journey Home Films Producer: Jesse Ikeman Exec. Producer: Richard Boddington Director: Richard Boddington Production Manager: Stewart Young D.O.P.: Stephen C Whitehead Key Cast: Natasha Henstridge, Steve Byers, Zackary Arthur, Morgan DiPietrantonio, John Tench, Colin Fox, Donovan Brown, Ted Whittall, Jeremy Ferdman, Keith Saulnier Shooting dates: Oct 2 - Oct 30/19 AKILLA'S ESCAPE Feature Films - Theatrical Canesugar Filmworks Producers: Jake Yanowski, Charles Officer Exec. Producers: Martin Katz, Karen Wookey, Michael A. Levine Director: Charles Officer Production Manager: Dallas Dyer D.O.P.: Maya Bankovic Key Cast: Saul Williams, Thamela Mpumlwana, Vic Mensa, Bruce Ramsay, Shomari Downer Shooting dates: May 14 - Jun 6/19 AND YOU THOUGHT YOU WERE NORMAL Feature Films - Streaming Side Three Media Producers: Leanne Davies, Tim Kowalski Exec. Producer: Colin Brunton Director: Tim Kowalski, Kevan Byrne Production Manager: Woody Whelan D.O.P.: Tim Kowalski Key Cast: Gary Numan, Owen Pallett, Tim Hill, Cam Hawkins, Steve Hillage Shooting dates: Jan 28 - Mar 5/19 AWAKE As of January 14, 2019 1 SHOT IN ONTARIO 2019 Feature Films - Streaming eOne / Netflix Producers: Mark Gordon, Paul Schiff Executive Producer: Whitney Brown Director: Mark Raso Production Manager: Szonja Jakovits D.O.P.: Alan Poon Key Cast: Gina Rodrigues Shooting dates: Aug 6 - Sep 27/19 CASTLE IN THE GROUND Feature Films - Theatrical 2623427 Ontario Inc. -

Actor and Activist Blair Underwood Raises Awareness of HIV/AIDS

RESEARCH FEBRUARY/MARCH 2013 BY SUSANNAH GORA Actor and Activist Blair Underwood Raises Awareness of HIV/AIDS ~e renowned actor has made it his mission to improve the lives of people with HIV/AIDS. Over the decades, he has captivated audiences with roles on TV shows such as L.A. Law, The Event, and Sex and the City; in movies like Deep Impact and Madea's Family Reunion; and in theatrical productions such as the recent Broadway revival of A Streetcar Named Desire. But behind the scenes, Blair Underwood has played a different role: the impassioned activist on a mission to improve people's lives, especially those with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which is the cause of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Through his years of tireless work, Underwood has become one of the most powerful voices in the fight against HIV/AIDS. It's essential, Underwood says, to create "conversation and awareness" around this still-stigmatized disease. And one of the least publicized and understood aspects of HIV/AIDS is its effect on the nervous system, known as neuro-AIDS. Activism has been an important part of Underwood's life for decades. Nearly 25 years ago, Underwood co-founded an organization called Artists for a New South Africa. Originally, the organization—which still exists today—was meant to bring attention to apartheid. But as apartheid was dismantled in the 1990s, explains Underwood, "We shifted our focus to HIV and AIDS." The impact of the disease on families in South Africa—especially children—"was what really shook me to my core," he says.