Durham Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Natural History of Wiltshire

The Natural History of Wiltshire John Aubrey The Natural History of Wiltshire Table of Contents The Natural History of Wiltshire.............................................................................................................................1 John Aubrey...................................................................................................................................................2 EDITOR'S PREFACE....................................................................................................................................5 PREFACE....................................................................................................................................................12 INTRODUCTORY CHAPTER. CHOROGRAPHIA.................................................................................15 CHOROGRAPHIA: LOCAL INFLUENCES. 11.......................................................................................17 EDITOR'S PREFACE..................................................................................................................................21 PREFACE....................................................................................................................................................28 INTRODUCTORY CHAPTER. CHOROGRAPHIA.................................................................................31 CHOROGRAPHIA: LOCAL INFLUENCES. 11.......................................................................................33 CHAPTER I. AIR........................................................................................................................................36 -

Mineral Resources Report for Wiltshire

Mineral Resource Information in Support of National, Regional and Local Planning Wiltshire (comprising Wiltshire and the Borough of Swindon) Commissioned Report CR/04/049N BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY COMMISSIONED REPORT CR/04/049N Mineral Resource Information in Support of National, Regional and Local Planning Wiltshire (comprising Wiltshire and the Borough of Swindon) G E Norton, D G Cameron, A J Bloodworth, D J Evans, G K Lott, I J Wilkinson, H F Burke, N A Spencer, and D E Highley This report accompanies the 1;100 000 scale map: Wiltshire (comprising Wiltshire and the Borough of Swindon) Mineral Resources Key words Mineral resource planning, Wiltshire, Swindon. Front cover Westbury Cement Works, Lafarge Cement UK (Blue Circle Cements), and Westbury White Horse. Bibliographical reference G E NORTON, D G CAMERON, A J BLOODWORTH, D J EVANS, G K LOTT, I J WILKINSON, H F BURKE, N A SPENCER, and D E HIGHLEY. 2004. Mineral Resource Information in Support of National, Regional and Local Planning. Wiltshire (comprising Wiltshire and the Borough of Swindon) British Geological Survey Commissioned Report, CR/04/049N. 12pp. Keyworth, Nottingham British Geological Survey 2004 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The full range of Survey publications is available from the British Geological Survey offices BGS Sales Desks at Nottingham, Edinburgh and London; see contact details below or shop online at Keyworth, Nottingham NG12 5GG www.geologyshop.com 0115B936 3100......................... Fax 0115B936 3200 e-mail: sales @bgs.ac.uk The London Information Office also maintains a reference www.bgs.ac.uk collection of BGS publications including maps for Online shop: www.geologyshop.com consultation. -

Wiltshire. Wilton

DlRECTORV. J WILTSHIRE. WILTON. 275 PUBLIC ESTABLISHMENTS. Registrars of Births, Deaths &; Marriages, Bishopstone Oemetery, Ditchampton, Jacob Whiley, supt l sub-district, Stanley A. Cudmer, Barford St. Martin; Fire Brigade, Market place, Francis James Pretty, capt Wilton sub-dist. Alfred Sheppard, The Square, Wilton Police Station, Market place, Sergt. Charles Townsend, & r constable I FUBLIC OFFICERS. Town Hall, Market place, Mrs. Hinton, keeper ' Collector of Poor's Rates, Robeort Beckett, Stoford Certifying Factory Surgeon, Charles Robert Straton L.R.C.P. & F.R.C.S.Edin., L.S.Sc. West lodge WILTON UNION. Wilton union comprises the following places :-Barford PLACES OF WORSHIP, with times of Services. St. Martin, Baverstock, Bemerton, Berwick St. James, SS. Mary & Nicholas Church, Rev. Guy Ronald Camp Bishopstone, Bower Ohalke, Broad Chalke, Burcombe bell M.A. rector ; Rev. Percy Richard Barrington Without, Compton, Chamberlayne, Dinton, Ebbes & 11 &; &. borne Wake, Fisherton-de-la-Mere, Fovant, Groveley Brown M.A. curate ; 8 a.m. 2.45 6.30 p.m. ; daily, 8 a.m. & 7 p.m Wood, Langford (Little), Netherhampton, South Congregational, Rev. Arthur Girling; ro.45 a.m. & 6 Newton Without, Stapleford, Steeple Langford, Wil p.m.; thurs. 7 p.m ton, Wishford (Great), Wylye or Wily. The popula Primitive Methodist (Salisbury Circuit); Rev. Herbert tion of the union in I9II was Io,2o3; area, 56,2o5 William Smith; ro.3o a. m. & 6 p.m.; thurs. 8 p.m acres; rateable value in rgrs, £7I,400 Wesleyan Methodist; 10.30 a..m. &; 6 p.m Board day, every alternate monday, at the Poor Law Institution, South Newton, at 2 p.m. -

Harnham Business Park Particulars.Pub

Harnham Business Park, Netherhampton Road, Salisbury, SP2 8PF Development Land Outline Planning Consent for Employment Uses, B1, B2 , B8, Motor Retail and Day Nursery Plots from 0.7 to 6.8 acres For Sale Freehold or Design & Build for Occupiers LOCATION Salisbury is an historic Cathedral City in Central Southern England. It has a resident population of 40,302 approximately and a Salisbury District population of 117,500 (Source: 2011 Census). Rail communications are provided by a main -line Station with frequent service to London (Waterloo) (90 minutes approx.). Road communications are well served to London via A303 (M3) (88 miles); Southampton via A36 (M27) (24 miles); Bristol via A36 (54 miles); Exeter via A303 (91 miles) (Source: The AA). SITUATION Harnham Business Park is situated 1 mile south west of Salisbury City Centre, fronting onto the A3094 Netherhampton Road, which connects the A36 Bristol/Southampton Road with the A338 Ringwood/Bournemouth and A354 to Blandford. DESCRIPTION Harnham Business Park comprises a total of 8.65 acres of development land. The site has been cleared and a new main spine road constructed, together with a junction onto the Netherhampton Road. All services are laid onto the site. Plot 5 at the rear of the Business Park has been developed for Booker Cash & Carry. The remaining 6.8 acres are available for development arranged as follows:- Plot 1 (frontage) 1.35 acres (0.55 ha) Plots 2-4 (frontage) 4.78 acres (1.93 ha) Plot 6 0.71 acres (0.29 ha) TENURE Freehold or New Lease. A service charge will be payable for the maintenance and upkeep of the shared Estate Road and services. -

Scheme Original (2016) Polling District Unitary Division Current

2017 Polling Original (2016) District Scheme Polling District Unitary Division Current (2016) Parish/ Parish Ward 1/12/2016 2017 New Parish New (2017) Parish Ward UPRN ADDRESS Number Road Locality City County Post Code 4 BI Fovant and Chalke Valley Netherhampton CH4 Salisbury Salisbury Harnham 10010443497 1 Bridgwater Close Harnham Salisbury Wiltshire SP2 8JS 4 BI Fovant and Chalke Valley Netherhampton CH5 Salisbury Salisbury Harnham 10010443498 2 Bridgwater Close Harnham Salisbury Wiltshire SP2 8JS 4 BI Fovant and Chalke Valley Netherhampton CH6 Salisbury Salisbury Harnham 10010443499 3 Bridgwater Close Harnham Salisbury Wiltshire SP2 8JS 4 BI Fovant and Chalke Valley Netherhampton CH7 Salisbury Salisbury Harnham 10010443500 4 Bridgwater Close Harnham Salisbury Wiltshire SP2 8JS 4 BI Fovant and Chalke Valley Netherhampton CH8 Salisbury Salisbury Harnham 10010443501 5 Bridgwater Close Harnham Salisbury Wiltshire SP2 8JS 4 BI Fovant and Chalke Valley Netherhampton CH9 Salisbury Salisbury Harnham 10010443502 6 Bridgwater Close Harnham Salisbury Wiltshire SP2 8JS 4 BI Fovant and Chalke Valley Netherhampton CH10 Salisbury Salisbury Harnham 10010443503 7 Bridgwater Close Harnham Salisbury Wiltshire SP2 8JS 4 BI Fovant and Chalke Valley Netherhampton CH11 Salisbury Salisbury Harnham 10010443504 8 Bridgwater Close Harnham Salisbury Wiltshire SP2 8JS 4 BI Fovant and Chalke Valley Netherhampton CH12 Salisbury Salisbury Harnham 10010443505 9 Bridgwater Close Harnham Salisbury Wiltshire SP2 8JS 4 BI Fovant and Chalke Valley Netherhampton CH13 Salisbury -

Quidhampton Village Newsletter April 2016

Quidhampton Village Newsletter April 2016 What’s On in April 2016 Quidhampton events in bold Thursday 7: Monthly pub quiz The White Horse 20.15 Friday 8 Monthly coffee morning South Wilts Sports Club from 10.00 Saturday 9: Grand National Day: watch at The White Horse Sunday 10 Music4Fun: bring and buy music sale South Wilts Sports Club 10.00-13.00 Monday 11 Term begins Bemerton St John’s School and Sarum Academy Tuesday 12 Introduction to sign language and the deaf community: St Michael’s Community Centre FREE everyone welcome 18.30 Wednesday 20: First monthly bike night at The White Horse Thursday 21: Bemerton Local History Society AGM. Hedley Davis Court 19.30 Saturday 23 Annual Parochial Church Council meeting over a shared meal at St Michael’s Community Centre 18.00 Sign up in St Andrews Saturday 23 St George’s Day and FA Cup Semi Final : Pimm’s, cream teas, pasties, pies and beer deals at The White Horse Tuesday 26 Bemerton Film Society Belle St John’s school 19.30 entrance £5 Thursday 28 Music4Fun open mic session South Wilts Sports Club 19.30 Sunday 1 May Parish Litter Pick White Horse 10.00 Bank Holiday Monday 2 May Advance notices: Friday 27 May HAPPY CIRCUS returns to Bemerton. Pre-circus fun from 17.00. Show begins 18.00. Bemerton Recreation Ground. In aid of St John’s Place. Booking now open. Family tickets £30. Individual £8. Under 3’s free (on adult’s lap) call 07513 344378 Friday 3 – Sunday 5 June: The White Horse Annual Beer Festival more details next time Saturday 11 June: celebrate the Queen’s 90th birthday at The White Horse with an afternoon of family fun Very advance notice: the Bus Pass Christmas Party will be on the 10th December. -

Salisbury & Wilton Walking

Updated Salisbury – The Walking Friendly City 2015 Salisbury is compact and easy to get around on foot. While Harnham, Cathedral and Britford Walks Avon Valley, Old Sarum and Bishopdown Walks Salisbury & Wilton walking one can appreciate its many historic buildings and enjoy Start point: Middle Start point: Walk 2c: the rivers, water meadows and parks. The rivers are of Guildhall Square for all walks on along Middle St. [It is worth making a diversion into Guildhall Square for all walks Stratford-sub-Castle and Bishopdown – 5 miles Street Meadow on the left to visit the pond and wetland area.] See: Walking Map international importance and home to an abundance of wildlife. Walk 1a: Town Path, Harnham, Cathedral Close – 2 miles Walk 2a: Riverside Path, Avon Valley Nature Reserve – 2.5 miles Riverside and wildlife, views over the City and Laverstock Down See: Return to the road and at the Town Path turn L past the Old Mill See: 1 [Follow section 1 of Walk 2a] At the wooden bridge do not cross A short walk from the city centre takes you into the countryside Gardens, ‘Constable’s views’, watermeadows, historic buildings Hotel, follow the path across the watermeadows back to the start. River Avon, wildlife, historic park, Salisbury Arts Centre to enjoy Salisbury’s landscape setting with views over the city. 1 Walk along the south side of the Market Square, go between 1 but continue straight ahead along a gravel path. After a small Walk 1d: Harnham Hill, Shaftesbury Drove, East Harnham meadows, Cross the Market Square to the Library and walk through Market bridge, keep to the edge of the river and continue on a boardwalk You can visit Old Sarum or relax in meadows of wildflowers and buildings to the Poultry Cross and turn R. -

Local Government Boundary Commission for England Report No

Local Government Boundary Commission For England Report No. 26 LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND REPORT NO. 26 LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMUISSION FOR ENGLAND CHAIRMAN Sir Edmund Coiapton, GOB, KBE DEPUTY CHAIRMAN Mr J la Rankin, QC MEMBERS The Countess of Albetnarle, DBE Mr T C Benfield Processor Michael Chisholm Sir Andrew Whe'atiey, CBE ivir P B Young, CBE To the Rt Hon Roy Jenkins, MP Secretary of State for the Home Department PROPOSALS FOR REVISED ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS TOR THE DISTRICT OF SALISBURY IN THE COUNTY OF WILTSHIRE 1. We, the Local Government Boundary Commission for England, having carried out our initial review of the electoral arrangements for the district of Salisbury in accordance with the requirements of section 63 and Schedule 9 to the Local Government Act 1972, present our proposals for the future electoral arrangements for that district. 2. In accordance with the procedure laid down in section 60(l) and (2) of the 1972 Act, notice was given on 13 May 1974. that we were to undertake this review. This was incorporated in a consultation letter addressed to the Salisbury District Council, copies of which were circulated to the Wiltshire County Council, Parish Councils and Parish Meetings in the district, the Members of Parliament for the constituencies concerned and the headquarters of the main political parties. Copies were also sent to the editors of the local newspapers circulating in the area and to the local government press. Notices inserted in the local press announced the start of the review and invited comments from members of the public and from any interested bodies. -

1999 No. 2924 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The

454890foot29-10-99 03:35:24 Pag Table: STATIN PPSysB Unit: pag1 STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 1999 No. 2924 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The District of Salisbury (Electoral Changes) Order 1999 Made ----- 22nd October 1999 Coming into force in accordance with article 1(2) Whereas the Local Government Commission for England, acting pursuant to section 15(4) of the Local Government Act 1992(), has submitted to the Secretary of State a report dated March 1999 on its review of the district of Salisbury together with its recommendations: And whereas the Secretary of State has decided to give effect, with modifications, to those recommendations: Now, therefore, the Secretary of State, in exercise of the powers conferred on him by sections 17() and 26 of the Local Government Act 1992, and of all other powers enabling him in that behalf, hereby makes the following Order: Citation, commencement and interpretation 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the District of Salisbury (Electoral Changes) Order 1999. (2) This Order shall come into force— (a) for the purposes of proceedings preliminary or relating to any election to be held on 1st May 2003, on 10th October 2002; (b) for all other purposes, on 1 May 2003. (3) In this Order— “district” means the district of Salisbury; “existing”, in relation to a ward, means the ward as it exists on the date this Order is made; and any reference to the map is a reference to the map prepared by the Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions marked “Map of the District of Salisbury (Electoral Changes) Order 1999”, and deposited in accordance with regulation 27 of the Local Government Changes for England Regulations 1994(). -

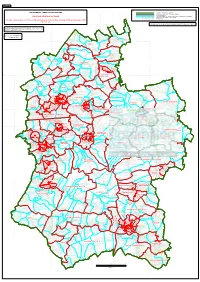

Wiltshire Map Showing New Wards.Pdf

SHEET 1, MAP 1 KEY THE BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND UNITARY AUTHORITY BOUNDARY PROPOSED ELECTORAL DIVISION BOUNDARY PARISH BOUNDARY ELECTORAL REVIEW OF WILTSHIRE PARISH BOUNDARY COINCIDENT WITH ELECTORAL DIVISION BOUNDARY CRICKLADE AND LATTON PROPOSED ELECTORAL DIVISION NAME LATTON CP PARISH NAME Final Recommendations for Electoral Division Boundaries in the Unitary Authority of Wiltshire November 2008 Sheet 1 of 6 PARISHES AFFECTED BY THE SALISBURY (PARISHES) ORDER 2008 OPERATIVE 1 APRIL 2009 This map is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of MARSTON the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office © Crown copyright. MAISEY Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. CP The Electoral Commission GD03114G 2008. Scale : 1cm = 0.08000 km LATTON CP Grid interval 5km ASHTON KEYNES CP OAKSEY CP CRUDWELL CP CRICKLADE AND LATTON CRICKLADE CP MINETY LEIGH CP MINETY CP HANKERTON CP P C H G U O OR B N CHARLTON CP E K PURTON CP O R B BRAYDON CP PURTON MALMESBURY EASTON GREY CP CP SOPWORTH LEA AND CLEVERTON CP SHERSTON MALMESBURY CP SHERSTON CP BRINKWORTH LYDIARD MILLICENT CP NORTON ST PAUL CP MALMESBURY LYDIARD TREGOZE WITHOUT CP LITTLE BRINKWORTH CP SOMERFORD CP W OO CP TT WOOTTON ON N B LUCKINGTON CP O AS BASSETT RT S H ET EAST T HULLAVINGTON CP GREAT SOMERFORD CP WOOTTON BASSETT CP DAUNTSEY CP WOOTTON BASSETT SOUTH SEE SHEET 3, MAP 3A T SEAGRY O CP C K STANTON ST QUINTIN CP E GRITTLETON CP N H CHRISTIAN MALFORD A M BROAD TOWN CP CP C LYNEHAM -

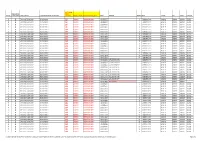

A303 Amesbury to Berwick Down Applications Appendix 15.2 Assessment Matrix

A303 Amesbury to Berwick Down TR010025 6.3 Environmental Statement Appendices Volume 1 6 Appendix 15.2 Assessment matrix APFP Regulation 5(2)(a) Planning Act 2008 Infrastructure Planning (Applications: Prescribed Forms and Procedure) Regulations 2009 October 2018 A303 Amesbury to Berwick Down Applications Appendix 15.2 Assessment Matrix Figure ID Application reference Applicant for 'other development' and brief description Assessment of cumulative effect with NSIP Proposed mitigation applicable to NSIP including any apportionment Residual cumulative effect Timescale 1 17/00280/VAR Variation of the pedestrian and cycle route scheme agreed under Considered in baseline Considered in baseline Considered in baseline Baseline Condition 27 of S/2009/1527 for the proposed permissive pedestrian and cycle path on the grassed over section of the former A344 to now be open to the public by 1st October 2017 (allowing a further year from the original agreed scheme to enable the proposed permissive path to establish itself prior to it being opened to the public) 2 S/2013/0102 Installation of interpretation panels, archaeological presentations and Considered in baseline Considered in baseline Considered in baseline Baseline associated works 3 S/2013/0101 Considered in baseline Considered in baseline Considered in baseline Baseline Creation of new access and associated works 4 17/00794/FUL Extension of existing fishing lakes Considered in future baseline Considered in future baseline Considered in future baseline Future Baseline (2021 and 2026) 5 14/02901/FUL -

A Handsome Georgian Village House

A handsome Georgian village house The Whitehouse, Netherhampton, Salisbury SP2 8PU Freehold Accommodation: Entrance Hall • Drawing Room • Sitting Room • Rear hall • Kitchen/Breakfast Room • Studio . Boot Room • Shower Room • Cloakroom Four Bedrooms • Family Bathroom • Shower Room Garden Description bedrooms, a stylish family With 17th Century origins and bathroom and a separate 18th Century additions, The shower room. Whitehouse is a charming and well-presented family home. Outside Lime rendered, with a The house sits in the centre of predominantly clay tiled roof, the small village of great care has been taken to Netherhampton. The pretty renovate the house in a garden is private and mainly laid sympathetic and considered to lawn. It runs down to style, preserving a host of far-reaching views over the original features. From the water meadows and countryside entrance hall, the elegant, beyond. The lawn is bordered dual-aspect drawing room has with both mature and young an open fire, oak floorboards trees and shrubs, including and French doors onto the Clematis, Bay, Hazel, Winter secluded terrace, the south- Jasmine, Magnolia, Plum and facing sash window benefits Apple trees. There are two from original shutters. A cosy areas of terrace, positioned to sitting room, with a catch the sun at different times woodburning stove and oak of the day, bordered with floorboards, is also south- Twisted Hazel, Amelanchier and facing, with original window an abundance of Roses. shutters. A light-filled rear hall is glazed along one wall, with Situation French doors onto the terrace. Netherhampton lies It leads through to a large approximately 2 miles west of kitchen/breakfast room with Salisbury city centre.