ORBIS MUSICÆ VOLUME XIV © 2007 by the Authors and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Puccini's Version of the Duet and Final Scene of "Turandot" Author(S): Janet Maguire Source: the Musical Quarterly, Vol

Puccini's Version of the Duet and Final Scene of "Turandot" Author(s): Janet Maguire Source: The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 74, No. 3 (1990), pp. 319-359 Published by: Oxford University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/741936 Accessed: 23-06-2017 16:45 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Oxford University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Musical Quarterly This content downloaded from 198.199.32.254 on Fri, 23 Jun 2017 16:45:10 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Puccini's Version of the Duet and Final Scene of Turandot JANET MAGUIRE ALTHOUGH it has been said that Puccini did not finish Turandot because he could not, I have always been convinced that he had the music for the duet and final scene clearly in mind and that he would have had his Turandot Finale ready for the publisher by the end of the year, 1924, had he survived his throat operation. The key to the completion of the opera lies in a relatively few pages of musical ideas sketched out in brief, schematic form. -

“Turandot” by Giacomo Puccini Libretto (English-Italian) Roles Personaggi

Giacomo Puccini - Turandot (English–Italian) 8/16/12 10:44 AM “Turandot” by Giacomo Puccini libretto (English-Italian) Roles Personaggi Princess Turandot - soprano Turandot, principessa (soprano) The Emperor Altoum, her father - tenor Altoum, suo padre, imperatore della Cina (tenore) Timur, the deposed King of Tartary - bass Timur, re tartaro spodestato (basso) The Unknown Prince (Calàf), his son - tenor Calaf, il Principe Ignoto, suo figlio (tenore) Liù, a slave girl - soprano Liú, giovane schiava, guida di Timur (soprano) Ping, Lord Chancellor - baritone Ping, Gran Cancelliere (baritono) Pang, Majordomo - tenor Pang, Gran Provveditore (tenore) Pong, Head chef of the Imperial Kitchen - tenor Pong, Gran Cuciniere (tenore) A Mandarin - baritone Un Mandarino (baritono) The Prince of Persia - tenor Il Principe di Persia (tenore) The Executioner (Pu-Tin-Pao) - silent Il Boia (Pu-Tin-Pao) (comparsa) Imperial guards, the executioner's men, boys, priests, Guardie imperiali - Servi del boia - Ragazzi - mandarins, dignitaries, eight wise men,Turandot's Sacerdoti - Mandarini - Dignitari - Gli otto sapienti - handmaids, soldiers, standard-bearers, musicians, Ancelle di Turandot - Soldati - Portabandiera - Ombre ghosts of suitors, crowd dei morti - Folla ACT ONE ATTO PRIMO The walls of the great Violet City: Le mura della grande Città Violetta (The Imperial City. Massive ramparts form a semi- (La Città Imperiale. Gli spalti massicci chiudono circle quasi that enclose most of the scene. They are interrupted tutta la scena in semicerchio. Soltanto a destra il giro only at the right by a great loggia, covered with è carvings and reliefs of monsters, unicorns, and rotto da un grande loggiato tutto scolpito e intagliato phoenixes, its columns resting on the backs of a mostri, a liocorni, a fenici, coi pilastri sorretti dal gigantic dorso di massicce tartarughe. -

MODELING HEROINES from GIACAMO PUCCINI's OPERAS by Shinobu Yoshida a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requ

MODELING HEROINES FROM GIACAMO PUCCINI’S OPERAS by Shinobu Yoshida A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music: Musicology) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Naomi A. André, Co-Chair Associate Professor Jason Duane Geary, Co-Chair Associate Professor Mark Allan Clague Assistant Professor Victor Román Mendoza © Shinobu Yoshida All rights reserved 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ...........................................................................................................iii LIST OF APPENDECES................................................................................................... iv I. CHAPTER ONE........................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION: PUCCINI, MUSICOLOGY, AND FEMINIST THEORY II. CHAPTER TWO....................................................................................................... 34 MIMÌ AS THE SENTIMENTAL HEROINE III. CHAPTER THREE ................................................................................................. 70 TURANDOT AS FEMME FATALE IV. CHAPTER FOUR ................................................................................................. 112 MINNIE AS NEW WOMAN V. CHAPTER FIVE..................................................................................................... 157 CONCLUSION APPENDICES………………………………………………………………………….162 BIBLIOGRAPHY.......................................................................................................... -

"Duetto a Tre": Franco Alfano's Completion of "Turandot" Author(S): Linda B

"Duetto a tre": Franco Alfano's Completion of "Turandot" Author(s): Linda B. Fairtile Source: Cambridge Opera Journal, Vol. 16, No. 2 (Jul., 2004), pp. 163-185 Published by: Cambridge University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3878265 Accessed: 23-06-2017 16:44 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3878265?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Cambridge University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Cambridge Opera Journal This content downloaded from 198.199.32.254 on Fri, 23 Jun 2017 16:44:32 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Cambridge Opera Journal, 16, 2, 163-185 ( 2004 Cambridge University Press DOI- 10.1017/S0954586704001831 Duetto a tre: Franco Alfano's completion of Turandot LINDA B. FAIRTILE Abstract: This study of the ending customarily appended to Giacomo Puccini's unfinished Turandot offers a new perspective on its genesis: that of its principal creator, Franco Alfano. Following Puccini's death in November 1924, the press overstated the amount of music that he had completed for the opera's climactic duet and final scene. -

Ian France - Opera Favourites from the Romantic Era

Ian France - Opera Favourites from the Romantic Era With suggestions of what versions to search out Bellini’s “Norma” “Mira, o Norma” Norma & Adalgisa, rivals in love, come to an understanding in this poignant duet CD: Montseratt Caballe &Fiorenzo Cossotto, cond.Cillario/LPO/RCA Caballe and Cossotto sing with great control and mostly softly (unlike Callas) YouTube: Anna Netrebko & Elina Garance Adalgisa (Garanca) pleads for Norma’s children to stay with her. In this concert version we don’t have to worry about Norma’s boys acting sensitively-our focus is on the heavenly music. As was customary in Italian operas at the time there is a fast, joyous cabaletta to round off the scene with Norma and Adalgisa promising to be lifelong “comrades”. Donizetti’s “Lucia di Lammermoor” “Sulla tomba” Edgar reflects on the tombs of his ancestors, Lucia joins him (turning his solo into a duet) and then the “big tune” is sung 3 times (listen out for a celebratory “wiggle” in the orchestra as they finish singing!) CD : Pavarotti & Sutherland cond.Bonynge/ROH/Decca Pavarotti and Sutherland were at their best in the Bel Canto repertoire. YouTube: Beczala & Netrebko In this extended scene Edgardo (Beczala) sings of his impending journey to France in the Stuart cause. Lucia (Netrebko) begs him to keep their love secret from her brother Enrico. Edgardo has sworn by his father’s grave to gain vengeance, but the music softens, the lovers kiss (cue applause!) Lucia sings “Verrano a te sull’aure” which Edgardo takes up and after her maid warns them to be on their way, both sing the “big tune” in unison. -

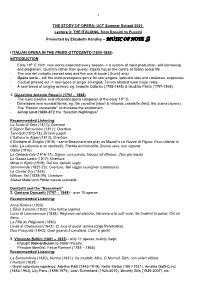

1 the STORY of OPERA: UCT Summer School 2021: Lecture 3

1 THE STORY OF OPERA: UCT Summer School 2021: Lecture 3: THE ITALIANS, from Rossini to Puccini Presented by Elizabeth Handley – MUSIC OF NOTE ♫ I ITALIAN OPERA IN THE PRIMO OTTOCENTO (1800-1850) INTRODUCTION - Early 19th C ItalY: new works expected every season -> a system of rapid production, self-borrowing and plagiarism. Quantity rather than quality. Opera house the centre of Italian social life. - The aria del sorbetto (sorbet aria) and the aria di baule ( [trunk] aria). - Opera seria – still the most prestigious genre for star singers: splendid sets and costumes, expensive. - Castrati phased out -> new types of singer emerged. Tenors allotted more major roles. - A new breed of singing actress, eg. Isabella Colbran (1785-1845) & Giuditta Pasta (1797-1865). 1. Gioachino Antonio Rossini (1792 – 1868) - The most creative and influential opera composer of the early 19th C. - Developed new musical forms, eg. the cavatina (slow) & virtuosic cabaletta (fast); the scena (scene). - The “Rossini crescendo”: to increase the excitement. - Jenny Lind (1820-87): the “Swedish Nightingale”. Recommended Listening: La Scala di Seta (1812): Overture Il Signor Beruschino (1812): Overture Tancredi (1812-13): Di tanti palpiti L’Italiana in Algeri (1813): Overture Il Barbiere di Siviglia (1816) - same Beaumarchais play as Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro: Ecco ridente in cielo, La calunnia e un venticello, Fredda ed immobile, Buona sera, mio signore Otello (1816) La Cenerentola (1816-17): Signor, una parola, Nacqui all’affanno...Non piu mesta La Gazza Ladra (1817): Overture Mosè in Egito (1818): Dal tuo stellato soglo Semiramide (1822-23): Overture, Bel raggio lusinghier (coloratura) Le Comte Ory (1828) William Tell (1828-29): Overture Stabat Mater and Petite messe solonelle Donizetti and the “Rossiniani” 2. -

Turandot: Good to Know 5 Production Information 6 Synopsis 7 the Principal Characters 9 the Principal Artists 10 the Composer 11 Turandot the Librettists 12

Study Guide Chorus Sponsor Season Sponsors Student Night at the Opera Sponsor Projected Translations Sponsor Making the Arts More Accessible® Education, Outreach and Audience Engagement Sponsors 1060 – 555 Main Street lower level, Centennial Concert Hall Winnipeg, MB, R3B 1C3 204-942-7479 www.manitobaopera.mb.ca For Student Night tickets or more information on student programs, contact Livia Dymond at 204-942-7470 or [email protected] Join our e-newsletter for exclusive behind-the-scenes content: Go to www.manitobaopera.mb.ca and click “Join Our Mailing List” welcome Contents Three Great Resources for Teaching Your Students About Opera 4 Turandot: Good to Know 5 Production Information 6 Synopsis 7 The Principal Characters 9 The Principal Artists 10 The Composer 11 Turandot The Librettists 12 About Musical Highlights 13 Nessun Dorma 14 The History of Turandot 15 Ancient China: Geography 16 People in Ancient China 17 A Short Overview of Opera 18 Bringing an Opera to the Stage 20 The Operatic Voice and Professional Singing 22 Glossary: Important Words in Opera 23 General Opera General Audience Etiquette 27 Manitoba Opera 28 Student Activities 29 Winnipeg Public Library Resources 36 TURANDOT 3 welcome Three Great Resources for Teaching Your Students About Opera 1. Student Night In order to expose student audiences to the glory of opera, Manitoba Opera created Student Night. It’s an affordable opportunity for students to watch the dress rehearsal, an exciting look at the art and magic of opera before the curtain goes up on Opening Night, when tension is high and anything can happen. -

Pittsburgh Opera Mounts Spectacular New Turandot Premiere of Never-Before-Seen Production

PITTSBURGHOPERA page 1 For Immediate Release March 4, 2011 Contact: Debra L. Bell, Director of Marketing and Communications Office: (412) 281-0912 ext 214 or [email protected] Pittsburgh Opera mounts spectacular new Turandot Premiere of never-before-seen production What: Giacomo Puccini’s opera Turandot Where: Benedum Center 7th Street and Penn Avenue, Downtown Pittsburgh When: Saturday, March 26, 8:00 PM Tuesday, March 29, 7:00 PM Friday, April 1, 8:00 PM Sunday, April 3, 2:00 PM Discover Yourself Run Time: 2 hours, 40 minutes, including two intermissions 2010-2011 Season Language: Sung in Italian with English titles projected above the stage Tickets: Start at $10 for all performances. Call 412-456-6666 for more information or visit www.pittsburghopera.org Pittsburgh, PA… Pittsburgh Opera premieres a never-before-seen production of Puccini’s opera Turandot in 4 performances at the Benedum Center, March 26 through April 3. With its dazzling sets and costumes, large orchestra and cast, and even Puccini’s original gongs, Pittsburgh Opera’s Turandot promises to be an intoxicating opera experience, showcasing spectacular production elements by the French-Canadian production team Renaud Doucet and Andre Barbe. Featuring the famous arias “Nessun dorma” and “In questa reggia”, all performances of Turandot take place at the Benedum Center in downtown Pittsburgh March 26, March 29, April 1 and April 3. Music Director Antony Walker conducts, returning to the U.S. after garnering enthusiastic reviews conducting The Barber of Seville at the Sydney Opera House. The story of Turandot, with origins in ancient Asian lore, is centered on the titular icy princess, who poses impossible riddles to her noble suitors and then cruelly beheads them when they guess the answers incorrectly. -

Dennis Brain Discography

DENNIS BRAIN ON RECORD A Comprehensive Discography Compiled by Robert L. Marshall Fourth Edition, 2011 FOREWORD This is the fourth, and no doubt final, revision of the “Comprehensive Inventory by Composer” section from my book, Dennis Brain on Record: A Comprehensive Discography of his Solo, Chamber and Orchestral Recordings, originally published in 1996, with a foreword by Gunther Schuller (Newton, Mass: Margun Music, Inc.). Most of the additions and corrections contained in the present list were brought to my attention by Dr. Stephen J. Gamble who, over the course of the past fifteen years, has generously shared his discographical findings with me. Although many of these newly listed items also appear in the discography section of the recently published volume Dennis Brain: A Life in Music, co-authored by Dr. Gamble and William C. Lynch (University of North Texas Press), it seemed useful nonetheless to make an updated, integral version of the “comprehensive” inventory available as well. There is one significant exception to the claim of “comprehensiveness” in the present compilation; namely, no attempt has been made here to update the information relating to Dennis Brain’s film studio activities. All the entries in that regard included here were already listed in the original publication of this discography. The total number of entries itemized here stands at 1,791. In the original volume it was 1,632. All the newly added items are marked in the first column with an asterisk after the composer’s name. (It will be interesting to see whether any further releases are still forthcoming.) The entries themselves have been updated in other respects as well. -

Vancouver Opera Study Guide – Turandot

STUDY GUIDE Queen Elizabeth Theatre I October 13, 19, 21 at 7:30pm I October 15 at 2:00pm Opera in three acts Conductor Jacques Lacombe I Director Renaud Doucet In Italian with English and Mandarin SurTitles™ Dress Rehearsal Wednesday, October 11, at 7pm Opera Experience Thursday, October 19th Backstage Tour 5:00 pm Performance Begins 7:30 pm CAST IN ORDER OF VOCAL APPEARANCE A Mandarin Peter Monaghan Liú, a young slave girl Marianne Fiset Calaf, the unknown prince Marcelo Puente Timur, his father, the dispossessed king of Tartary Alain Couloumbe Prince of Persia TBD Ping, Grand Chancellor Jonathan Beyer Pang, General Purveyor Julius Ahn Pong, Chief Cook Joseph Hu The Emperor Altoum Sam Chung Handmaids Melanie Krueger Karen Ydenberg Princess Turandot Amber Wagner With the Vancouver Opera Chorus as guards, executioner’s assistants, priests, mandarins, dignitaries, wise men and attendants, and the Vancouver Opera Orchestra. Scenic Designer / Costume Designer André Barbe Associate Conductor / Chorus Director Leslie Dala Principal Répétiteur / Children’s Chorus Director Kinza Tyrrell Choreographer Roxanne Foster Lighting Designer Guy Simon Wig Designer Susan Manning Musical Preparation Kimberley-Ann Bartczak Stage Manager Ingrid Turk Assistant Director Kathleen Stakenas Assistant Lighting Designer Andrew Pye English SurTitle™ Operator Sarah Jane Pelzer Assistant Stage Managers Marijka Asbeek Brusse Emma Hammond The performance will last approximately 2 hours and 45 minutes. There will be two intermissions. First produced at Milan, Teatro alla Scala, April 25, 1926. First produced by Vancouver Opera, April 27, 1972. Scenery, properties and costumes for this production were constructed at Minnesota Opera Shops and are jointly owned by Minnesota Opera, Pittsburgh Opera, Seattle Opera, Utah Opera, Cincinnati Opera and Opera Philadelphia. -

111053-54 Bk Bhmissa

111334-35 bk Turandot EU.qxd 2/11/08 13:23 Page 8 revealed. They end by threatening Calaf with their are left alone, she rigid as a statue and veiled. Calaf daggers. Shouting is heard, as soldiers drag in Timur calls on this Princess of death and of ice to descend to and Liù, two who must know the Prince’s name. earth. He rushes forward and tears off her veil, to 4 Turandot appears, and they bow down to the Turandot’s anger; he may tear her veil but not touch PUCCINI ground, except for Ping, who comes forward to tell her soul. The Prince takes Turandot in his arms, and her that they now have the means to discover the draws her towards the pavilion, kissing her, but she Prince’s name. Calaf claims that Timur and Liù know draws away, now seeking his pity. 0 Calaf declares nothing, but Liù steps forward and tells Turandot that his love for her, as dawn breaks; he has conquered Turandot she alone knows the stranger’s name and will keep it and her heart has melted. ! For the first time now secret. 5 Calaf tries to protect her and on Turandot’s she sheds tears, telling him of her first fear of him. orders is bound, while Liù is tortured 6 claiming Finally Calaf reveals to her his name. love as the reason for her strength in resistance. She is RIA CALL happy to suffer for her beloved Prince, as the Scene 2 A AS executioner is called for. -

A Cognitive Approach to Medieval Mode

Phenomena, Poiēsis, and Performance Profiling: Temporal-Textual Emphasis and Creative Process Analysis in Turandot at the Metropolitan Opera JOSHUA NEUMANN [1] University of Florida ABSTRACT: Amidst discussions regarding the nature of a musical work, tensions within and between score- and performance-based approaches often increase ideological entrenchment. Opera’s textual and visual elements, along with its inherently social nature, both simultaneously complicate understanding of a work’s nature and provide interdisciplinary analytical inroads. Analysis of operatic performance faces challenges of how to interrogate onstage musical behaviors, and how they relate to both dramatic narrative and an opera’s identity. This article applies Martin Heidegger’s dichotomy of technē and poiēsis to relationships between scores, performances, and works, characterizing works as conceptual, and scores and performances as tangible embodiments. Opera scholarship relies primarily upon scores, creating a lacuna of sound-based examinations. Adapting analyses developed in CHARM’s “Mazurka Project,” this essay incorporates textual considerations into tempo hierarchy as a means of asserting each performance’s nuanced uniqueness and thus provides a window into performers’ creative processes. Interviews with the performers considered in this study confirmed postulations derived from analyzing temporal-textual emphases. This approach is adaptable to other expressive elements employed in creating a role onstage. In addition to the hybrid empirical-hermeneutic application,