Island Lake, Manitoba

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Origin of the Name Manitoba

On May 2, 1870, Sir John A. Macdonald The Origin of the Name The Narrows of Lake Manitoba (on PTH 68, 60 km west of the junction of announced that a new province was to enter Manitoba PTHs 6 and 68) Confederation under The Manitoba Act. He said the province’s name had been chosen for its pleasant sound and its associations with the The name Manitoba originated in the languages original inhabitants of the area. of the Aboriginal people who lived on the Prairies and travelled the waters of Lake Both the Cree and Assiniboin terms, and the Manitoba. legends and events associated with their use, are preserved forever in the name Manitoba. A These people, the Cree and Assiniboin First plaque commemorating its origin is located on Nations, introduced European explorers, traders the east side of the Lake Manitoba Narrows. and settlers to the region and its waterways. They also passed on to the newcomers the ancient names and poetic legends associated with the places they inhabited. More than two centuries of contact and trade between the Europeans and First Nations produced a blending of their languages. From Aboriginal name and legend to official title of the province, the evolution of the name Manitoba mirrors the history of the region. At the Lake Manitoba Narrows a strong wind can send waves washing against the limestone During the Red River Resistance of 1869-70, rocks of an offshore island. The unique sound Spence joined Louis Riel’s Métis Council. In from the waves is said to be the Manitou, or the spring of 1870, delegates from this council Great Spirit (in Ojibway, “Manito-bau”). -

Grand Rapids GS Short Term Extension Licence Request (2014

360 Portage Ave (16) Winnipeg Manitoba Canada R3C 0G8 Telephone / No de téléphone : 204-360-3018 Fax / No de télécopieur : 204-360-6136 [email protected] 2014 10 30 Mr. Rob Matthews Manager, Water Use Licensing Manitoba Conservation and Water Stewardship Box 16 - 200 Saulteaux Crescent Winnipeg MANITOBA R3J 3W3 Dear Mr. Matthews: GRAND RAPIDS WATER POWER SHORT-TERM EXTENSION LICENCE REQUEST We request a five year short-term extension licence for the Grand Rapids Generating Station under the provisions of Section 92(1) of Water Power Regulation 25/88R. We have included a Short Term Extension Report as supporting documentation and will continue to work with your Section to address this Water Power licence. Manitoba Hydro continues to operate the Grand Rapids Generating Station in accordance with the Final Licence issued on May 30, 1975 under the Water Power Act. The Final Licence expires on January 2, 2015. Manitoba Hydro requested a renewal licence on December 17, 2010. However, due to licensing requirements for other projects, Manitoba Hydro is requesting a short-term extension licence to allow the licence renewal to occur at a later date. Please call me at 204-360-3018 if you need additional information. Yours truly, pp: Brian Giesbrecht W.V. Penner, P. Eng. Manager Hydraulic Operations Department Encl. MJD/sl/ 00112-07311-0014_00 WATER POWER ACT LICENCES GRAND RAPIDS GENERATING STATION SHORT TERM LICENCE EXTENSION APPLICATION SUPPORTING DOCUMENTATION Prepared for: Manitoba Water Stewardship 200 Saulteaux Crescent Winnipeg MB R3J 3W3 Prepared by: Manitoba Hydro 360 Portage Avenue Winnipeg MB R3C 0G8 October 29, 2014 Report No: PS&O – 14/08 HYDRAULIC OPERATIONS DEPARTMENT POWER SALES & OPERATIONS DIVISION GENERATION OPERATIONS WATER POWER ACT LICENCES GRAND RAPIDS SHORT TERM LICENCE EXTENSION APPLICATION SUPPORTING DOCUMENTATION Originally signed by P.Chanel Originally signed by PREPARED BY: P.Chanel P. -

Wallace Mining and Mineral Prospects in Northern

r Geology V f .ibrary TN 27 7A3V/1 WALLACE MINING AND MINERAL PROSPECTS IN NORTHERN MANITOBA THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES University of British Columbia D. REED LIBRARY The RALPH o DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ,-XGELES, CALIF. Northern Manitoba Bulletins Mining and Mineral Prospects in Northern Manitoba BY R. C. WALLACE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY OF GOVERNMENT OP MANITOBA OFFICE OF COMMISSIONER OF NORTHERN MANITOBA The Pas, Manitoba Northern Manitoba Bulletins Mining and Mineral Prospects in Northern Manitoba BY R. C. WALLACE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY OF GOVERNMENT OF MANITOBA OFFICE OF COMMISSIONER OF NORTHERN MANITOBA The Pas, Manitoba CONTENTS Chapter Page I. Introductory 5 II. Geological features ... 7 III. History of Mining Development 12 IV. Metallic Deposits: (A) Mineral belt north of The Pas .... 20 (1) Flin Flon and Schist Lake Districts. .... ....20 (2) Athapapuskow Lake District ..... ....27 (3) Copper and Brunne Lake Districts .....30 (4) Herb and Little Herb Lake Districts .... .....31 (5) Pipe Lake, Wintering Lake and Hudson Bay Railway District... 37 (B) Other mineral areas .... .....37 V. Non-metallic Deposits 38 (a) Structural materials 38 (ft) Fuels 38 (c) Other deposits. 39 VI. The Economic Situatior 40 VII. Bibliography 42 Appendix: Synopsis of Regulations governing the granting of mineral rights.. ..44 NORTHERN MANITOBA NORTHERN MANITOBA Geology Library INTRODUCTORY CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTORY Scope of Bulletin The purpose of this bulletin is to give a short description of the mineral deposits, in so far as they have been discovered and developed, in the territory which was added to the Province of Manitoba in the year 1912. -

Geomorphic and Sedimentological History of the Central Lake Agassiz Basin

Electronic Capture, 2008 The PDF file from which this document was printed was generated by scanning an original copy of the publication. Because the capture method used was 'Searchable Image (Exact)', it was not possible to proofread the resulting file to remove errors resulting from the capture process. Users should therefore verify critical information in an original copy of the publication. Recommended citation: J.T. Teller, L.H. Thorleifson, G. Matile and W.C. Brisbin, 1996. Sedimentology, Geomorphology and History of the Central Lake Agassiz Basin Field Trip Guidebook B2; Geological Association of CanadalMineralogical Association of Canada Annual Meeting, Winnipeg, Manitoba, May 27-29, 1996. © 1996: This book, orportions ofit, may not be reproduced in any form without written permission ofthe Geological Association ofCanada, Winnipeg Section. Additional copies can be purchased from the Geological Association of Canada, Winnipeg Section. Details are given on the back cover. SEDIMENTOLOGY, GEOMORPHOLOGY, AND HISTORY OF THE CENTRAL LAKE AGASSIZ BASIN TABLE OF CONTENTS The Winnipeg Area 1 General Introduction to Lake Agassiz 4 DAY 1: Winnipeg to Delta Marsh Field Station 6 STOP 1: Delta Marsh Field Station. ...................... .. 10 DAY2: Delta Marsh Field Station to Brandon to Bruxelles, Return En Route to Next Stop 14 STOP 2: Campbell Beach Ridge at Arden 14 En Route to Next Stop 18 STOP 3: Distal Sediments of Assiniboine Fan-Delta 18 En Route to Next Stop 19 STOP 4: Flood Gravels at Head of Assiniboine Fan-Delta 24 En Route to Next Stop 24 STOP 5: Stott Buffalo Jump and Assiniboine Spillway - LUNCH 28 En Route to Next Stop 28 STOP 6: Spruce Woods 29 En Route to Next Stop 31 STOP 7: Bruxelles Glaciotectonic Cut 34 STOP 8: Pembina Spillway View 34 DAY 3: Delta Marsh Field Station to Latimer Gully to Winnipeg En Route to Next Stop 36 STOP 9: Distal Fan Sediment , 36 STOP 10: Valley Fill Sediments (Latimer Gully) 36 STOP 11: Deep Basin Landforms of Lake Agassiz 42 References Cited 49 Appendix "Review of Lake Agassiz history" (L.H. -

Lake Manitoba and Lake St. Martin Outlet Channels

Project Description Lake Manitoba and Lake St. Martin Outlet Channels Prepared for: Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency Submitted by: Manitoba Infrastructure January 2018 Project Description – January 2018 Table of Contents 1 GENERAL INFORMATION AND CONTACTS ................................................... 1 1.1 Nature of the Project and Proposed Location ..................................................... 1 1.2 Proponent Information ........................................................................................ 3 1.2.1 Name of the Project ......................................................................................... 3 1.2.2 Name of the Proponent ................................................................................... 3 1.2.3 Address of the Proponent ................................................................................ 3 1.2.4 Chief Executive Officer .................................................................................... 3 1.2.5 Principal Contact Person ................................................................................. 3 1.3 Jurisdictions and Other Parties Consulted .......................................................... 6 1.4 Environmental Assessment Requirements ......................................................... 7 1.4.1 Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2012 (Canada) ............................ 7 1.4.2 The Environment Act (Manitoba) ..................................................................... 8 1.5 Other Regulatory Requirements ........................................................................ -

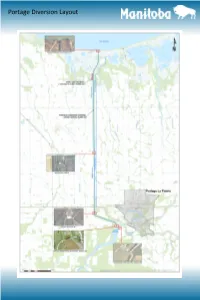

Portage Diversion Layout Recent and Future Projects

Portage Diversion Layout Recent and Future Projects Assiniboine River Control Structure Public and worker safety improvements Completed in 2015 Works include fencing, signage, and safety boom Electrical and mechanical upgrades Ongoing Works include upgrades to 600V electrical distribution system, replacement of gate control system and mo- tor control center, new bulkhead gate hoist, new stand-by diesel generator fuel/piping system and new ex- terior diesel generator Portage Diversion East Outside Drain Reconstruction of 18 km of drain Completed in 2013 Replacement of culverts beneath three (3) railway crossings Completed in 2018 Recent and Future Projects Portage Diversion Outlet Structure Construction of temporary rock apron to stabilize outlet structure Completed in 2018 Conceptual Design for options to repair or replace structure Completed in 2018 Outlet structure major repair or replacement prioritized over next few years Portage Diversion Channel Removal of sedimentation within channel Completed in 2017 Groundwater/soil salinity study for the Portage Diversion Ongoing—commenced in 2016 Enhancement of East Dike north of PR 227 to address freeboard is- sues at design capacity of 25,000 cfs Proposed to commence in 2018 Multi-phase over the next couple of years Failsafe assessment and potential enhancement of West Dike to han- dle design capacity of 25,000 cfs Prioritized for future years—yet to be approved Historical Operating Guidelines Portage Diversion Operating Guidelines 1984 Red River Floodway Program of Operation Operation Objectives The Portage Diversion will be operated to meet these objectives: 1. To provide maximum benefits to the City of Winnipeg and areas along the Assiniboine River downstream of Portage la Prairie. -

?Pi\ Tqm[ Jmvmi\P°

Photo: Thomas Fricke L % 45 5 65-#)&*.789:5* 65-#)0 .7(: ; " henever the University of Mani- The department of geological sciences, the are touched by it every day,” Elias says. “Hu- toba starts a new building project oldest of its kind in Western Canada, has mans rely on natural resources and the Earth on campus it piques Bill Brisbin’s been uncovering history in Manitoba for the is the supplier.” curiosity. What’s being constructed is of less past century. And it is celebrating its centen- He notes that geology also offers insights interest to the geology professor emeritus ary with a number of alumni events and pro- into climate change because it shows what than what the excavation uncovers – a slice jects. has happened in the past. of Manitoba’s history. Fundraising continues for two permanent “Geology is a fundamental in the world we Brisbin says when crews dug the ground for commemorative displays: a Mosaic Map of live in,” says Prof. Jim Teller. He points out the new lecture theatre at St. John’s College Manitoba to showcase the province’s ma- that where people spend their vacations, in 2008, it exposed clay deposits that had jor geological terrains in actual rock, and a where farmers grow their crops, the resour- been scoured off a retreating ice sheet about 5.5-metre History Wall to chronicle the de- ces that are mined, and even the landscapes 10,000 years ago. partment’s history, achievements, alumni of that photographers decide to shoot are all de- But you don’t have to dig deep to go even distinction and academic and professional termined by geology. -

And Along the Fairford River, Pineimuta Lake, Lake St

Lake Manitoba Regulation Review Advisory Committee Regulation of Water Levels on Lake Manitoba and along the Fairford River, Pineimuta Lake, Lake St. Martin and Dauphin River and Related Issues A Report to the Manitoba Minister of Conservation Volume 1 Summary Report July 2003 The Lake Manitoba Regulation Review Advisory Committee Summary Report, July 2003 Lake Manitoba Regulation Review Advisory Committee Regulation of Water Levels on Lake Manitoba and along the Fairford River, Pineimuta Lake, Lake St. Martin and Dauphin River and Related Issues A Report to the Manitoba Minister of Conservation Volume 1 Summary Report July 2003 The Lake Manitoba Regulation Review Advisory Committee Cover Photo: Looking west along the Fairford River from the Fairford River Water Control Structure. Summary Report, July 2003 Lake Manitoba Regulation Review Advisory Committee Executive Summary The Lake Manitoba Regulation Review Advisory Committee was appointed in 2001, following complaints to the Minister of Conservation with respect to relatively high water levels on Lake Manitoba. The Terms of Reference developed to guide the Lake Manitoba Regulation Review Advisory Committee are as follows: Determine the most acceptable and practicable range of regulation within which the levels of Lake Manitoba might be controlled; Decide if it is practicable and desirable to maintain the lake at certain levels during different seasons of the year, and from year to year, and if so recom- mend specific levels or range of levels; Determine the best course of action for water levels along the Fairford River, Lake Pineimuta, Lake St. Martin and the Dauphin River, including the best course of action with respect to the operation of the Fairford Dam; and, Examine existing data with respect to the present water quality of Lake Mani- toba and compare to historical water quality. -

Pike and Walleye in the Rocky Lake-Root-Reader Marsh

Manuscript Report No. 04-01 PIKE AND WALLEYE IN THE ROCKY LAKE- ROOT-READER MARSH COMPLEX by Walt Lysack 2004 Manitoba Water Stewardship Fisheries Branch TABLE OF CONTENTS DESCRIPTION AND HISTORY OF THE STUDY AREA ................................................ 4 ROOT – READER PIKE STUDY..................................................................................... 7 ROCKY LAKE FISH STOCK MONITORING PROGRAM ............................................. 24 ROCKY LAKE CREEL SURVEY................................................................................... 29 DISCUSSION................................................................................................................ 39 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................. 52 REFERENCES.............................................................................................................. 53 LIST OF TABLES Table 1. Rocky Lake’s water chemistry during the 1980s. ............................................ 19 Table 2. Daily angling duration parameters................................................................... 32 Table 3. Parameters of fishing effort and catches of pike, walleye and bass ................ 33 Table 4. Parameters of CUE, no. fish angler hour ................................................... 34 Table 5. Parameters of individual pike and walleye weights ......................................... 35 Table 6. Parameters of kept walleye CUE reported on the creel survey forms. ........... -

Lundar Beach Provincial Park Management Plan 2 | Lundar Beach Provincial Park

Lundar Beach Provincial Park Management Plan 2 | Lundar Beach Provincial Park Table of Contents 1. Introduction ................................ 3 2. Park History ................................ 3 3. Park Attributes ........................... 3 3.1 Natural ....................................................... 4 3.2 Recreational ............................................... 4 3.3 Additional Features ................................... 4 4. Park Management Framework ... 4 4.1 Park Classification ..................................... 4 4.2 Park Purpose ............................................. 4 4.3 Land Use Categories .................................. 5 5. Park Management Guidelines..... 6 5.1 Natural Values ........................................... 6 5.2 Recreation ................................................. 6 5.3 Commercial Operations ............................. 6 Appendix .......................................... 7 A. Park Classification and Land Use Categories Bibliography ..................................... 8 Manitoba Conservation and Water Stewardship Parks and Protected Spaces Branch Autumn 2013 Management Plan | 3 history of use. Information collected was then used to prepare a draft plan. Public input on the draft plan was collected primarily through the Manitoba Parks website. Once the public consultation process was completed in August of 2013, the plan was finalized based on planning objectives and any new information received through the consultation process. This management plan will guide the work of -

Lake Manitoba Water Qality & Ecosystem Health Workshop

Lake Manitoba and its Watershed: Knowledge Gaps & Next Steps Sunrise over Lake Manitoba at Delta Marsh (© Marliese Peterson) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................. 1 2. Introduction.............................................................................................................................. 2 2.1. Background to Lake Manitoba .......................................................................................... 2 2.2. Rationale for workshop ..................................................................................................... 2 3. Water Levels & Regulation..................................................................................................... 4 3.1. Presentations ..................................................................................................................... 4 3.2. Knowledge Gaps ............................................................................................................... 4 3.1. Next Steps For Top-Ranked Knowledge Gaps ................................................................. 8 4. Watershed Management & Landscape Processes .............................................................. 12 4.1. Presentations ................................................................................................................... 12 4.2. Knowledge Gaps ............................................................................................................ -

The Birds of Western Manitoba

THE AUK' A Q•UARTERLY JOURNAL OF ORNITHOLOGY. VOL. III. APRIL• I886. •NJO. THE BIRDS OF WESTERN MANITOBA. ERNEST E. T. SETON. Fo• the sake of conciseness and conveuience of refk:rence I will first distinguishthe variousnatural divisionsof the country. I. The Assiniboinc Valley, or first prairie steppe. This includes all of Manitoba south and west of' a line drawn fi'om Pembina Mountain north, just west of Portage la Prairie, and thence nortMvest to Fort Pelly. This line is also the eastern edge of the cretnceousformation. The district is essentially a prairie region, the only wooded tracts of any extent being the fiat tops of the elew•tedtable Innds, known as Pemhina, Turtle, Riding, and Duck Mountains. The first two are at the United States Boundary. The other'sare on the northeast edge of this region. Carberryis just north of the AssiniboineRiver, a5out the center of the region. The Big Plain is an mmsuallv fiat prairie, betweenCnrberry aud the Riding Mountaiu. The Big Swamp is a spruceaud tamaracswamp, between (2arl)errvand the rive•'. Mnose Mountain is just outsideand west of Manitoba, at the head of the Souris River. QffAppelle is on the Q3•'Ap- pelle River, outsideand west of Manitoba, one lmndred miles up the river fi'omits junction with the Assiniboine. The obserwttiousfor the region are my own, as I have visited nearly everypart of it. I have. however,received nmch yahruble 146 SEzo•on the Birds of PVesternManitoba. tApril assistancefrom Mr. G. F. Guernsey,who is responsiblefor the records fi'om Q•u'Appelle. 2. The Red River Valley.