Redalyc.New Rican Voices. Un Muestrario / a Sampler at the Millenium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zukofsky), 736–37 , 742–43 Asian American Poetry As, 987–88 “ABC” (Justice), 809–11 “Benefi T” Readings, 1137–138 Abolitionism

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00336-1 - The Cambridge History of: American Poetry Edited by Alfred Bendixen and Stephen Burt Index More information Index “A” (Zukofsky), 736–37 , 742–43 Asian American poetry as, 987–88 “ABC” (Justice), 809–11 “benefi t” readings, 1137–138 abolitionism. See also slavery multilingual poetry and, 1133–134 in African American poetry, 293–95 , 324 Adam, Helen, 823–24 in Longfellow’s poetry, 241–42 , 249–52 Adams, Charles Follen, 468 in mid-nineteenth-century poetry, Adams, Charles Frances, 468 290–95 Adams, John, 140 , 148–49 in Whittier’s poetry, 261–67 Adams, L é onie, 645 , 1012–1013 in women’s poetry, 185–86 , 290–95 Adcock, Betty, 811–13 , 814 Abraham Lincoln: An Horatian Ode “Address to James Oglethorpe, An” (Stoddard), 405 (Kirkpatrick), 122–23 Abrams, M. H., 1003–1004 , 1098 “Address to Miss Phillis Wheatley, academic verse Ethiopian Poetess, Who Came literary canon and, 2 from Africa at Eight Year of Age, southern poetry and infl uence of, 795–96 and Soon Became Acquainted with Academy for Negro Youth (Baltimore), the Gospel of Jesus Christ, An” 293–95 (Hammon), 138–39 “Academy in Peril: William Carlos “Adieu to Norman, Bonjour to Joan and Williams Meets the MLA, The” Jean-Paul” (O’Hara), 858–60 (Bernstein), 571–72 Admirable Crichton, The (Barrie), Academy of American Poets, 856–64 , 790–91 1135–136 Admonitions (Spicer), 836–37 Bishop’s fellowship from, 775 Adoff , Arnold, 1118 prize to Moss by, 1032 “Adonais” (Shelley), 88–90 Acadians, poetry about, 37–38 , 241–42 , Adorno, Theodor, 863 , 1042–1043 252–54 , 264–65 Adulateur, The (Warren), 134–35 Accent (television show), 1113–115 Adventure (Bryher), 613–14 “Accountability” (Dunbar), 394 Adventures of Daniel Boone, The (Bryan), Ackerman, Diane, 932–33 157–58 Á coma people, in Spanish epic Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Twain), poetry, 49–50 183–86 Active Anthology (Pound), 679 funeral elegy ridiculed in, 102–04 activist poetry. -

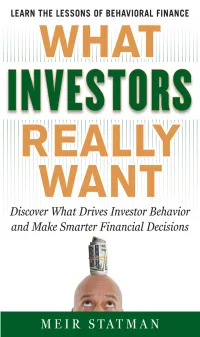

WHAT INVESTORS REALLY WANT Discover What Drives Investor Behavior and Make Smarter Financial Decisions

WHAT INVESTORS REALLY WANT Discover What Drives Investor Behavior and Make Smarter Financial Decisions MEIR STATMAN New York Chicago San Francisco Lisbon London Madrid Mexico City Milan New Delhi San Juan Seoul Singapore Sydney Toronto Copyright © 2011 by Meir Statman. All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978-0-07-174166-8 MHID: 0-07-174166-6 The material in this eBook also appears in the print version of this title: ISBN: 978-0-07-174165-1, MHID: 0-07-174165-8. All trademarks are trademarks of their respective owners. Rather than put a trademark symbol after every occurrence of a trademarked name, we use names in an editorial fashion only, and to the benefi t of the trademark owner, with no intention of infringement of the trademark. Where such designations appear in this book, they have been printed with initial caps. McGraw-Hill eBooks are available at special quantity discounts to use as premiums and sales promotions, or for use in corporate training programs. To contact a representative please e-mail us at [email protected]. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold with the understanding that neither the author nor the publisher is engaged in rendering legal, accounting, securities trading, or other professional services. -

CAPRICCIO Songbook

CAPRICCIO KARAOKE SongBOOK ITALIA – ENGLAND – SPANIEN DEUTSCHLAND – SCHWEIZ – PORTUGAL – FRANCE - BALKAN KARAOKE ItaliA www.capricciomusic.ch [email protected] Aktualisiert am: 01. Februar 2013 Artist Title 2 Black e Berte' Waves of Love (in alto Mare) 360 Gradi Baba bye 360 Gradi Sandra 360 Gradi & Fiorello E poi non ti ho vista piu 360 Gradi e Fiorello E poi non ti ho vista più (K5) 400 colpi Prendi una matita 400 Colpi Se puoi uscire una domenica 78 Bit Fotografia 883 Pezzali Max Aereoplano 883 Pezzali Max Bella vera 883 Pezzali Max Bella Vera (K5) 883 Pezzali Max Chiuditi nel cesso 883 Pezzali Max Ci sono anch'io 883 Pezzali Max Come deve andare 883 Pezzali Max Come mai 883 Pezzali Max Come mai (K5) 883 Pezzali Max Come mai_(bachata) 883 Pezzali Max Come maiBachata (K5i) 883 Pezzali Max Con dentro me 883 Pezzali Max Credi 883 Pezzali Max Cumuli 883 Pezzali Max Dimmi perche' 883 Pezzali Max Eccoti 883 Pezzali Max Fai come ti pare 883 Pezzali Max Fai come ti pare 883 Pezzali Max Favola semplice 883 Pezzali Max Gli anni 883 Pezzali Max Grazie Mille (K5) 883 Pezzali Max Grazie mille 1 883 Pezzali Max Grazie mille 2 883 Pezzali Max Hanno Ucciso L'Uomo Ragno (K5) 883 Pezzali Max Hanno ucciso l'uomo ragno 1 883 Pezzali Max hanno ucciso l'uomo ragno 2 883 Pezzali Max Il meglio deve ancora arrivare 883 Pezzali Max Il mio secondo tempo 883 Pezzali Max Il mondo insieme a te 883 Pezzali Max Il mondo Insieme a Te (K5) 883 Pezzali Max Innamorare tanto 883 Pezzali Max Io ci saro' 883 Pezzali Max Jolly blue 883 Pezzali Max La dura legge del -

DOCUMENT RESUME :CS 202 729 a Handbodk for Instruction In

DOCUMENT RESUME ----- ED 123 640 :CS 202 729 TITLE A Handbodk for Instruction in Communication Skills. ' INSTITUTION Lincolnshire-Prairie View El4mentary School District, Deerfield; Ill. PUB DATE Jun 75 NOTE 158p.; Not available in hard copy due to margin al to legibility of original document EDRS PRICE MF-$0.83 Plus Postage. HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Behavioral Objectives; Compositibn 'Skills (Literary); CuxricUlum Guides! Elementary Education;* *English Instruction; *Language Arts; Listening; Spelling 4 A ABSTRACT This handbook, which complements another' handbook designed for reading instruction, focuses on the'behavioral objectives in the four language arts skills of spelling, writing, listening, and speaking. The first section of'the handbook contains an introductory statement, a diagram of the programdesign, and.a list of the affective objectives. The other two sections of the handbook outline detailed learning objectives and specific activities in each of the four skill areas for grades one through three and for grades four through eight. (JM) *********************44****************************************t**44*** Documents acquired by EPIC include many informl unpublidEed . * * materials not available from other sources. ERIC makes every effort * * to obtain the best copy available. Nevertheless, items ofmarginal* * reproducibility are often encountered and this affects the quality * * of the microfiche and hardcopy reproductions ERIC makes available * * via the ERIC Document Reproduction Service (EDRS),. EDRS is -

TZNTHEBESTOFTIZIANOFERRO È Ora in Preorder Su Itunes

MARTEDì 4 NOVEMBRE 2014 #TZNTHEBESTOFTIZIANOFERRO è ora in preorder su iTunes. 61 canzoni, tutti i successi, 16 inediti, i duetti e le rarità TZN - The Best Of Tiziano Ferro è ora in preorder su iTunes #IMPERDIBILE E' da oggi in preorder su iTunes il primo best di Questi tutti i brani... Tiziano Ferro con 61 canzoni, tutti i successi, 16 inediti, i duetti e le rarità 1 Lo stadio 2 Incanto LA REDAZIONE 3 Senza scappare mai più 4 La fine 5 L'amore è una cosa semplice [email protected] SPETTACOLINEWS.IT 6 Troppo buono 7 Per dirti ciao! 8 Hai delle isole negli occhi 9 L'ultima notte al mondo 10 La differenza tra me e te 11 Each Tear (feat. Tiziano Ferro) [Italian Version] 12 Scivoli di nuovo 13 Il sole esiste per tutti 14 Indietro 15 Il regalo più grande 16 Alla Mia Età Pag. 1 / 3 17 E fuori e' buio 18 E raffaella è mia 1 Ti scatterò una foto 2 Ed ero contentissimo 3 Stop! dimentica 4 Se il mondo si fermasse 5 Ti voglio bene 6 Universal Prayer 7 Non me lo so spiegare 8 Sere nere 9 Xverso 10 Le cose che non dici 11 Rosso relativo 12 Imbranato 13 L'olimpiade 14 Xdono 15 Il vento 16 Angelo mio 17 Sulla mia pelle 18 Quando ritornerai 1 (Tanto)3 (Mucho Version) 2 Latina 3 Aria di vita (Acoustic Version) 4 Difendimi per sempre (Demo) 5 L'amore e basta! (Demo) 6 Cambio Casa 7 Le passanti (Live @ "Che Tempo Che Fa") 8 Eri come l'oro ora sei come loro 9 Il re di chi ama troppo (Live In Roma) 10 La differenza tra me e te 11 Sere nere (Brazilian Version) 12 Liebe ist einfach / L'amore è una cosa semplice 1 Cuestion de Feeling Pag. -

Tinkuy Boletín De

Escritoras puertorriqueñas en el siglo XXI: creación y crítica Ana Belén Martín Sevillano (ed.) TINKUY BOLETÍN DE INVESTIGACIÓN Y DEBATE Nº 18 – 2012 © 2011, Section d’Études hispaniques Département de littératures et de langues modernes Faculté des arts et des sciences Université de Montréal ISSN 1913-0481 Director fundador Juan C. Godenzzi Secretario/coordinador Nicolas Beauclair Comité editorial Ana Belén Martín Sevillano Catherine Poupeney-Hart Enrique Pato Maldonado James Cisneros Javier Rubiera Juan C. Godenzzi Comité asesor Estela Bartol Sara Smith Víctor Fernández Comité científico Albino Chacón Gutiérrez (Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica) Angelita Martínez (Universidad de Buenos Aires) Azucena Palacios (Universidad Autónoma de Madrid) Bruce Mannheim (University of Michigan) Daniel Chamberlain (Queen’s University) Elisabel Larriba (Université de Provence - UMR Telemme) John Lipski (The Pennsylvania State University) Fermín del Pino Díaz (CSIC-Madrid) Jorge Duany (Universidad de Puerto Rico, Río Piedras) Stefan Pfänder (Albert-Ludwigs Universität, Freiburg) Héctor Urzáiz (Universidad de Valladolid) Tinkuy cuenta con una versión impresa (ISSN 1913-0473) y una versión electrónica (ISSN 1913-0481) http://www.littlm.umontreal.ca/recherche/publications.html [email protected] TINKUY nº18, 2012 Section d’études hispaniques Université de Montréal Introducción Ana Belén Martín Sevillano, “Escritura y mujer en Puerto Rico hoy” 6 Creación Marta Aponte Alsina, El invernadero del doctor Pietri 10 Yolanda Arroyo Pizarro, Cómo se tejen -

El Estado De La Biodiversidad Para La Alimentación Y La Agricultura En Guatemala

INFORMES DE LOS PAÍSES EL ESTADO DE LA BIODIVERSIDAD PARA LA ALIMENTACIÓN Y LA AGRICULTURA EN GUATEMALA El presente informe nacional ha sido preparado por las autoridades nacionales del país como una contribución a la publicación de la FAO, El estado de la biodiversidad para la alimentación y la agricultura en el mundo. La Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Agricultura y la Alimentación (FAO) pone este documento a disposición de las personas interesadas, conforme a la petición de la Comisión de Recursos Genéticos para la Alimentación y la Agricultura. Los datos que contiene el informe no han sido verificados por la FAO, su contenido es responsabilidad exclusiva de los autores y las opiniones expresadas en el mismo no representan necesariamente el punto de vista o la política de la FAO o de sus Miembros. Las denominaciones empleadas en este producto informativo y la forma en que aparecen presentados los datos que contiene no implican, de parte de la FAO, juicio alguno sobre la condición jurídica o nivel de desarrollo de los países, territorios, ciudades o zonas, o de sus autoridades, ni respecto a la delimitación de sus fronteras o límites. La mención de empresas o productos de fabricantes en particular, estén o no patentados, no implica que la FAO los apruebe o recomiende en preferencia a otros de naturaleza similar que no se mencionan. PRESENTACIÓN El Consejo Nacional de Áreas Protegidas (CONAP) es el punto focal del Convenio sobre la Diversidad Biológica (CDB), por lo tanto, es el encargado de implementar los objetivos de dicho Convenio. Por otro lado, en el nivel internacional se ha visto la necesidad de integrar la conservación y la utilización sostenible de la biodiversidad para el bienestar, tal como fue puesto de manifiesto en la décima tercera reunión de las partes en el CDB en el año 2016, mediante la declaración de Cancún producto de la serie de reuniones de alto nivel. -

Leisure Pass Group

Explorer Guidebook Empire State Building Attraction status as of Sep 18, 2020: Open Advanced reservations are required. You will not be able to enter the Observatory without a timed reservation. Please visit the Empire State Building's website to book a date and time. You will need to have your pass number to hand when making your reservation. Getting in: please arrive with both your Reservation Confirmation and your pass. To gain access to the building, you will be asked to present your Empire State Building reservation confirmation. Your reservation confirmation is not your admission ticket. To gain entry to the Observatory after entering the building, you will need to present your pass for scanning. Please note: In light of COVID-19, we recommend you read the Empire State Building's safety guidelines ahead of your visit. Good to knows: Free high-speed Wi-Fi Eight in-building dining options Signage available in nine languages - English, Spanish, French, German, Italian, Portuguese, Japanese, Korean, and Mandarin Hours of Operation From August: Daily - 11AM-11PM Closings & Holidays Open 365 days a year. Getting There Address 20 West 34th Street (between 5th & 6th Avenue) New York, NY 10118 US Closest Subway Stop 6 train to 33rd Street; R, N, Q, B, D, M, F trains to 34th Street/Herald Square; 1, 2, or 3 trains to 34th Street/Penn Station. The Empire State Building is walking distance from Penn Station, Herald Square, Grand Central Station, and Times Square, less than one block from 34th St subway stop. Top of the Rock Observatory Attraction status as of Sep 18, 2020: Open Getting In: Use the Rockefeller Plaza entrance on 50th Street (between 5th and 6th Avenues). -

Edición Especial Curated by Sweety's Members Bryan Rodriguez

Sweety’s Radio: Edición Especial Curated by Sweety’s members Bryan Rodriguez Cambana, Julia Mata, Eduardo Restrepo Castaño and Ximena Izquierdo Ugaz. On View: June 27 through July 30, 2017 Interview Dates: Friday, June 30, July 7, July 14 and July 21 from 6-8P Gallery Hours: Tuesday – Sunday, 12-6P Episode 3: Emanuel Xavier On View: July 11 through July 16, 2017 Interview: Friday, July 14 from 6-8P, hosted by Sweety’s member Ximena Izquierdo Ugaz This year marks the 20th anniversary Emanuel Xavier’s self-published chapbook Pier Queen, a poetic manifesto about his personal experiences coming of age as a former street hustler, drug dealer/addict, homelessness and survivor of child abuse. To celebrate this LGBTQ Latinx and POC milestone, Rebel Satori Press has reissued the book with brand new cover art featuring a photograph by Richard Renaldi that captures the spirit and defiance of the Christopher Street West Side Highway piers. As part of Sweety’s Radio: Edicion Especial we will be honoring the anniversary of this chapbook with an exhibition and reception. On Friday, July 14, Xavier will be joined by percussionist Joyce Jones to recreate the spirit of late 90s poetry readings from the book Pier Queen in celebration of the 20th Anniversary of this landmark collection by a former homeless pier queen who went on to become one of the most significant voices of the LGBT and Latinx poetry movements. Drawn from Xavier’s personal archives as well as artists in conversation with his work, the exhibition spans several bodies of work from throughout Xavier’s career; from videos, event flyers, fan notes, memorabilia from that era as well as photographs by Richard Renaldi and artwork by Gabriel Garcia Roman. -

THE CYCLONE, 834 Surf Avenue at West 10Th Street, Brooklyn

Landmarks Preservation Commission July 12, 1988; Designation List 206 LP-1636 THE CYCLONE, 834 Surf Avenue at West 10th Street, Brooklyn. Built 1927. Inventor Harry c. Baker. Engineer Vernon Keenan. Landmark Site: Borough of Brooklyn Tax Map Block 8697, Lot 4 in part consisting of the land on which the described improvement is situated. On September 15, 1987, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the cyclone and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 12). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Six witnesses spoke in favor of designation, including the ride's owner, whose support was given dependant upon his ability to perform routine repair and maintenance. One witness spoke in opposition to designation. The Commission has received many letters in favor of designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS Summary Descended from the ice slides enjoyed in eighteenth-century Russia, through the many changes incorporated by French and American inventors, the Cyclone has been one of our country's premier roller coasters since its construction in 1927. Designed by engineer Vernon Keenan and built by noted amusement ride inventor Harry C. Baker for Jack and Irving Rosenthal, the Cyclone belongs to an increasingly rare group of wood-track coasters; modern building codes make it irreplaceable. The design of its twister-type circuit and the enormous weight of the cars allow the trains to travel on their own momentum after being carried up to the first plunge by mechanical means. Now part of Astroland amusement park, the Cyclone is not only a well recognized feature of Coney Island, where the first "modern" coaster was built in 1884, but, sadly, is the only roller coaster still operating there. -

La Diáspora Puertorriqueña: Un Legado De Compromiso the Puerto Rican Diaspora: a Legacy of Commitment

Original drawing for the Puerto Rican Family Monument, Hartford, CT. Jose Buscaglia Guillermety, pen and ink, 30 X 30, 1999. La Diáspora Puertorriqueña: Un Legado de Compromiso The Puerto Rican Diaspora: A Legacy of Commitment P uerto R ican H eritage M o n t h N ovember 2014 CALENDAR JOURNAL ASPIRA of NY ■ Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños ■ El Museo del Barrio ■ El Puente Eugenio María de Hostos Community College, CUNY ■ Institute for the Puerto Rican/Hispanic Elderly La Casa de la Herencia Cultural Puertorriqueña ■ La Fundación Nacional para la Cultura Popular, PR LatinoJustice – PRLDEF ■ Música de Camara ■ National Institute for Latino Policy National Conference of Puerto Rican Women – NACOPRW National Congress for Puerto Rican Rights – Justice Committee Puerto Rico Federal Affairs Administration www.comitenoviembre.org *with Colgate® Optic White® Toothpaste, Mouthwash, and Toothbrush + Whitening Pen, use as directed. Use Mouthwash prior to Optic White® Whitening Pen. For best results, continue routine as directed. COMITÉ NOVIEMBRE Would Like To Extend Is Sincerest Gratitude To The Sponsors And Supporters Of Puerto Rican Heritage Month 2014 City University of New York Institute for the Puerto Rican/Hispanic Elderly Colgate-Palmolive Company Puerto Rico Convention Bureau The Nieves Gunn Charitable Fund Embassy Suites Hotel & Casino, Isla Verde, PR Bronx Lebanon Hospital Center American Airlines John Calderon Rums of Puerto Rico United Federation of Teachers Hotel la Concha Compañia de Turismo de Puerto Rico Hotel Copamarina Acacia Network Omni Hotels & Resorts Carlos D. Nazario, Jr. Banco Popular de Puerto Rico Dolores Batista Shape Magazine Hostos Community College, CUNY MEMBER AGENCIES ASPIRA of New York Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños El Museo del Barrio El Puente Eugenio María de Hostos Community College/CUNY Institute for the Puerto Rican/Hispanic Elderly La Casa de la Herencia Cultural Puertorriqueña, Inc. -

CR- MARCH 3-9-11.Qxd

SUPPLEMENT TO THE CITY RECORD THE CITY COUNCIL-STATED MEETING OF TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 30, 2010 28 PAGES THE CITY RECORD THE CITY RECORD Official Journal of The City of New York U.S.P.S.0114-660 Printed on paper containing 40% post-consumer material VOLUME CXXXVIII NUMBER 46 WEDNESDAY, MARCH 9, 2011 PRICE $4.00 PROPERTY DISPOSITION Finance . .544 Police . .545 Contract Administration Unit . .545 Citywide Administrative Services . .543 Health and Hospitals Corporation . .544 TABLE OF CONTENTS Small Business Services . .545 Municipal Supply Services . .543 Health and Mental Hygiene . .545 PUBLIC HEARINGS & MEETINGS Procurement . .545 Auction . .543 Agency Chief Contracting Officer . .545 City Council . .537 AGENCY PUBLIC HEARINGS Sale by Sealed Bid . .543 Homeless Services . .545 City University . .541 Parks and Recreation . .546 Police . .543 Contracts and Procurement . .545 AGENCY RULES City Planning Commission . .541 Housing Authority . .545 PROCUREMENT Taxi and Limousine Commission . .546 Community Boards . .541 Purchasing Division . .545 City University . .544 SPECIAL MATERIALS Information Technology and Board of Correction . .541 City Planning . .546 Citywide Administrative Services . .544 Telecommunications . .545 Collective Bargaining . .546 Employees’ Retirement System . .541 Municipal Supply Services . .544 Executive Division . .545 Changes in Personnel . .546 Franchise and Concession Review Vendor Lists . .544 Juvenile Justice . .545 LATE NOTICES Committee . .541 Correction . .544 Parks and Recreation . .545 Community Boards . .547 Landmarks Preservation Commission . .541 Design and Construction . .544 Contract Administration . .545 Health and Hospitals Corporation . .547 Transportation . .543 Contract Section . .544 Revenue and Concessions . .545 READERS GUIDE . .548 THE CITY RECORD MICHAEL R. BLOOMBERG, Mayor EDNA WELLS HANDY, Commissioner, Department of Citywide Administrative Services. ELI BLACHMAN, Editor of The City Record.