Universal Minds Explaining the New Science of Evolutionary Psychology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolutionary Biology of Decision Making

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications, Department of Psychology Psychology, Department of 2008 The Evolutionary Biology of Decision Making Jeffrey R. Stevens University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/psychfacpub Part of the Psychiatry and Psychology Commons Stevens, Jeffrey R., "The Evolutionary Biology of Decision Making" (2008). Faculty Publications, Department of Psychology. 523. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/psychfacpub/523 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Psychology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, Department of Psychology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in BETTER THAN CONSCIOUS? DECISION MAKING, THE HUMAN MIND, AND IMPLICATIONS FOR INSTITUTIONS, ed. Christoph Engel and Wolf Singer (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2008), pp. 285-304. Copyright 2008 Massachusetts Institute of Technology & the Frankfurt Institute for Advanced Studies. Used by permission. 13 The Evolutionary Biology of Decision Making Jeffrey R. Stevens Center for Adaptive Behavior and Cognition, Max Planck Institute for Human Development, 14195 Berlin, Germany Abstract Evolutionary and psychological approaches to decision making remain largely separate endeavors. Each offers necessary techniques and perspectives which, when integrated, will aid the study of decision making in both humans and nonhuman animals. The evolutionary focus on selection pressures highlights the goals of decisions and the con ditions under which different selection processes likely influence decision making. An evolutionary view also suggests that fully rational decision processes do not likely exist in nature. -

Evolution by Natural Selection, Formulated Independently by Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace

UNIT 4 EVOLUTIONARY PATT EVOLUTIONARY E RNS AND PROC E SS E Evolution by Natural S 22 Selection Natural selection In this chapter you will learn that explains how Evolution is one of the most populations become important ideas in modern biology well suited to their environments over time. The shape and by reviewing by asking by applying coloration of leafy sea The rise of What is the evidence for evolution? Evolution in action: dragons (a fish closely evolutionary thought two case studies related to seahorses) 22.1 22.4 are heritable traits that with regard to help them to hide from predators. The pattern of evolution: The process of species have changed evolution by natural and are related 22.2 selection 22.3 keeping in mind Common myths about natural selection and adaptation 22.5 his chapter is about one of the great ideas in science: the theory of evolution by natural selection, formulated independently by Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace. The theory explains how T populations—individuals of the same species that live in the same area at the same time—have come to be adapted to environments ranging from arctic tundra to tropical wet forest. It revealed one of the five key attributes of life: Populations of organisms evolve. In other words, the heritable characteris- This chapter is part of the tics of populations change over time (Chapter 1). Big Picture. See how on Evolution by natural selection is one of the best supported and most important theories in the history pages 516–517. of scientific research. -

Psycholinguistics

11/09/2013 Psycholinguistics What do these activities have in common? What kind of process is involved in producing and understanding language? 1 11/09/2013 Questions • What is psycholinguistics? • What are the main topics of psycholinguistics? 9.1 Introduction • * Psycholinguistics is the study of the language processing mechanisms. Psycholinguistics deals with the mental processes a person uses in producing and understanding language. It is concerned with the relationship between language and the human mind, for example, how word, sentence, and discourse meaning are represented and computed in the mind. 2 11/09/2013 9.1 Introduction * As the name suggests, it is a subject which links psychology and linguistics. • Psycholinguistics is interdisciplinary in nature and is studied by people in a variety of fields, such as psychology, cognitive science, and linguistics. It is an area of study which draws insights from linguistics and psychology and focuses upon the comprehension and production of language. • The scope of psycholinguistics • The common aim of psycholinguists is to find out the structures and processes which underline a human’s ability to speak and understand language. • Psycholinguists are not necessarily interested in language interaction between people. They are trying above all to probe into what is happening within the individual. 3 11/09/2013 The scope of psycholinguistics • At its heart, psycholinguistic work consists of two questions. – What knowledge of language is needed for us to use language? – What processes are involved in the use of language? The “knowledge” question • Four broad areas of language knowledge: Semantics deals with the meanings of sentences and words. -

Balanced Biosocial Theory for the Social Sciences

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2004 Balanced biosocial theory for the social sciences Michael A Restivo University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Restivo, Michael A, "Balanced biosocial theory for the social sciences" (2004). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 1635. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/5jp5-vy39 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BALANCED BIOSOCIAL THEORY FOR THE SOCIAL SCIENCES by Michael A. Restivo Bachelor of Arts IPIoridkijSjlarrhcIJiuAHsrsity 2001 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillm ent ofdœnxpnnnnenkfbrthe Master of Arts Degree in Sociology Departm ent of Sociology College of Liberal Arts Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas M ay 2004 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 1422154 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. -

Psychology, Meaning Making and the Study of Worldviews: Beyond Religion and Non-Religion

Psychology, Meaning Making and the Study of Worldviews: Beyond Religion and Non-Religion Ann Taves, University of California, Santa Barbara Egil Asprem, Stockholm University Elliott Ihm, University of California, Santa Barbara Abstract: To get beyond the solely negative identities signaled by atheism and agnosticism, we have to conceptualize an object of study that includes religions and non-religions. We advocate a shift from “religions” to “worldviews” and define worldviews in terms of the human ability to ask and reflect on “big questions” ([BQs], e.g., what exists? how should we live?). From a worldviews perspective, atheism, agnosticism, and theism are competing claims about one feature of reality and can be combined with various answers to the BQs to generate a wide range of worldviews. To lay a foundation for the multidisciplinary study of worldviews that includes psychology and other sciences, we ground them in humans’ evolved world-making capacities. Conceptualizing worldviews in this way allows us to identify, refine, and connect concepts that are appropriate to different levels of analysis. We argue that the language of enacted and articulated worldviews (for humans) and worldmaking and ways of life (for humans and other animals) is appropriate at the level of persons or organisms and the language of sense making, schemas, and meaning frameworks is appropriate at the cognitive level (for humans and other animals). Viewing the meaning making processes that enable humans to generate worldviews from an evolutionary perspective allows us to raise news questions for psychology with particular relevance for the study of nonreligious worldviews. Keywords: worldviews, meaning making, religion, nonreligion Acknowledgments: The authors would like to thank Raymond F. -

Evolution, Politics and Law

Valparaiso University Law Review Volume 38 Number 4 Summer 2004 pp.1129-1248 Summer 2004 Evolution, Politics and Law Bailey Kuklin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Bailey Kuklin, Evolution, Politics and Law, 38 Val. U. L. Rev. 1129 (2004). Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr/vol38/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Valparaiso University Law School at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Valparaiso University Law Review by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Kuklin: Evolution, Politics and Law VALPARAISO UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW VOLUME 38 SUMMER 2004 NUMBER 4 Article EVOLUTION, POLITICS AND LAW Bailey Kuklin* I. Introduction ............................................... 1129 II. Evolutionary Theory ................................. 1134 III. The Normative Implications of Biological Dispositions ......................... 1140 A . Fact and Value .................................... 1141 B. Biological Determinism ..................... 1163 C. Future Fitness ..................................... 1183 D. Cultural N orm s .................................. 1188 IV. The Politics of Sociobiology ..................... 1196 A. Political Orientations ......................... 1205 B. Political Tactics ................................... 1232 V . C onclusion ................................................. 1248 I. INTRODUCTION -

Microevolution and the Genetics of Populations Microevolution Refers to Varieties Within a Given Type

Chapter 8: Evolution Lesson 8.3: Microevolution and the Genetics of Populations Microevolution refers to varieties within a given type. Change happens within a group, but the descendant is clearly of the same type as the ancestor. This might better be called variation, or adaptation, but the changes are "horizontal" in effect, not "vertical." Such changes might be accomplished by "natural selection," in which a trait within the present variety is selected as the best for a given set of conditions, or accomplished by "artificial selection," such as when dog breeders produce a new breed of dog. Lesson Objectives ● Distinguish what is microevolution and how it affects changes in populations. ● Define gene pool, and explain how to calculate allele frequencies. ● State the Hardy-Weinberg theorem ● Identify the five forces of evolution. Vocabulary ● adaptive radiation ● gene pool ● migration ● allele frequency ● genetic drift ● mutation ● artificial selection ● Hardy-Weinberg theorem ● natural selection ● directional selection ● macroevolution ● population genetics ● disruptive selection ● microevolution ● stabilizing selection ● gene flow Introduction Darwin knew that heritable variations are needed for evolution to occur. However, he knew nothing about Mendel’s laws of genetics. Mendel’s laws were rediscovered in the early 1900s. Only then could scientists fully understand the process of evolution. Microevolution is how individual traits within a population change over time. In order for a population to change, some things must be assumed to be true. In other words, there must be some sort of process happening that causes microevolution. The five ways alleles within a population change over time are natural selection, migration (gene flow), mating, mutations, or genetic drift. -

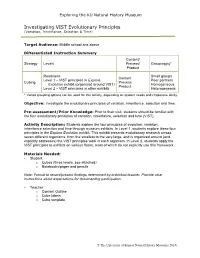

Investigating VIST Evolutionary Principles (Variation, Inheritance, Selection & Time)

Exploring the KU Natural History Museum Investigating VIST Evolutionary Principles (Variation, Inheritance, Selection & Time) Target Audience: Middle school and above Differentiated Instruction Summary Content/ Strategy Levels Process/ Grouping(s)* Product Readiness Small groups Content Level 1 – VIST principles in Explore Peer partners Cubing Process Evolution exhibit (organized around VIST) Homogeneous Product Level 2 – VIST principles in other exhibits Heterogeneous * Varied grouping options can be used for this activity, depending on student needs and chaperone ability. Objective: Investigate the evolutionary principles of variation, inheritance, selection and time. Pre-assessment/Prior Knowledge: Prior to their visit, students should be familiar with the four evolutionary principles of variation, inheritance, selection and time (VIST). Activity Description: Students explore the four principles of evolution: variation, inheritance selection and time through museum exhibits. In Level 1, students explore these four principles in the Explore Evolution exhibit. This exhibit presents evolutionary research across seven different organisms, from the smallest to the very large, and is organized around (and explicitly addresses) the VIST principles work in each organism. In Level 2, students apply the VIST principles to exhibits on various floors, most of which do not explicitly use this framework. Materials Needed: • Student o Cubes (three levels, see attached) o Notebooks/paper and pencils Note: Format to record/present findings determined by individual teacher. Provide clear instructions about expectations for documenting participation. • Teacher o Content Outline o Cube labels o Cube template © The University of Kansas Natural History Museum (2014) Exploring the KU Natural History Museum Content: VIST* Overview There are four principles at work in evolution—variation, inheritance, selection and time. -

The Three Meanings of Meaning in Life: Distinguishing Coherence, Purpose, and Significance

The Journal of Positive Psychology Dedicated to furthering research and promoting good practice ISSN: 1743-9760 (Print) 1743-9779 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rpos20 The three meanings of meaning in life: Distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance Frank Martela & Michael F. Steger To cite this article: Frank Martela & Michael F. Steger (2016) The three meanings of meaning in life: Distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance, The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11:5, 531-545, DOI: 10.1080/17439760.2015.1137623 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2015.1137623 Published online: 27 Jan 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 425 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rpos20 Download by: [Colorado State University] Date: 06 July 2016, At: 11:55 The Journal of Positive Psychology, 2016 Vol. 11, No. 5, 531–545, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2015.1137623 The three meanings of meaning in life: Distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance Frank Martelaa* and Michael F. Stegerb,c aFaculty of Theology, University of Helsinki, P.O. Box 4, Helsinki 00014, Finland; bDepartment of Psychology, Colorado State University, 1876 Campus Delivery, Fort Collins, CO 80523-1876, USA; cSchool of Behavioural Sciences, North-West University, Vanderbijlpark, South Africa (Received 25 June 2015; accepted 3 December 2015) Despite growing interest in meaning in life, many have voiced their concern over the conceptual refinement of the con- struct itself. Researchers seem to have two main ways to understand what meaning in life means: coherence and pur- pose, with a third way, significance, gaining increasing attention. -

Sexual Behavior and Satisfaction in Same-Sex and Different-Sex Relationships

Sexual Behavior and Satisfaction in Same-Sex and Different-Sex Relationships Taylor Orth Department of Sociology, Stanford University Author Contact Information: 450 Serra Mall Building 120, Room 30D Stanford, CA 94305 [email protected] (281) 772-0155 1 Sexual Behavior and Satisfaction in Same-Sex and Different-Sex Relationships Abstract: Among both academics and the lay public remains a widespread and taken- for-granted belief that male and female sexuality are fundamentally different and that men and women in sexual relationships compromise on such differences. More recently, however, social scientists have begun to question the extent to which gender gaps in sexual desire may be socially rather than biologically determined. Because collecting accurate and representative data on sexual behavior within relationships is often challenging, very little empirical evidence has been available to scientifically disentangle these competing perspectives. This study evaluates variation in the sexual behavior and satisfaction of same-sex and different-sex couples through an analysis of two nationally representative American surveys, How Couples Meet and Stay Together (HCMST) and The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health). Findings demonstrate that women in same-sex relationships have sex less often than other couple pairings. Men in same-sex relationships report significantly lower sexual satisfaction and higher rates of non-monogamy relative to other couples, even after controlling for relevant factors. Overall, the results from this study support the notion that sexual relationships function differently in the absence of a male or female partner, but present a less deterministic and more socially complex perspective than has traditionally been accepted. -

Between Psychology and Philosophy East-West Themes and Beyond

PALGRAVE STUDIES IN COMPARATIVE EAST-WEST PHILOSOPHY Between Psychology and Philosophy East-West Themes and Beyond Michael Slote Palgrave Studies in Comparative East-West Philosophy Series Editors Chienkuo Mi Philosophy Soochow University Taipei City, Taiwan Michael Slote Philosophy Department University of Miami Coral Gables, FL, USA The purpose of Palgrave Studies in Comparative East-West Philosophy is to generate mutual understanding between Western and Chinese philoso- phers in a world of increased communication. It has now been clear for some time that the philosophers of East and West need to learn from each other and this series seeks to expand on that collaboration, publishing books by philosophers from different parts of the globe, independently and in partnership, on themes of mutual interest and currency. The series also publishs monographs of the Soochow University Lectures and the Nankai Lectures. Both lectures series host world-renowned philosophers offering new and innovative research and thought. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/16356 Michael Slote Between Psychology and Philosophy East-West Themes and Beyond Michael Slote Philosophy Department University of Miami Coral Gables, FL, USA ISSN 2662-2378 ISSN 2662-2386 (electronic) Palgrave Studies in Comparative East-West Philosophy ISBN 978-3-030-22502-5 ISBN 978-3-030-22503-2 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-22503-2 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2020. This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence and indicate if changes were made. -

Meaning in Life in Psychotherapy: the Perspective of Experienced Psychotherapists

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette College of Education Faculty Research and Publications Education, College of 11-2015 Meaning in life in psychotherapy: The perspective of experienced psychotherapists Clara E. Hill University of Maryland - College Park Yoshi Kanazawa Meigi Gakuin University - Tokyo, Japan Sarah Knox Marquette University, [email protected] Iris Schauerman University of Maryland - College Park Darren Loureiro University of Maryland - College Park See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.marquette.edu/edu_fac Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Hill, Clara E.; Kanazawa, Yoshi; Knox, Sarah; Schauerman, Iris; Loureiro, Darren; James, Danielle; Carter, Imani; King, Shakeena; Razzak, Suad; Scarff, Melanie; and Moore, Jasmine, "Meaning in life in psychotherapy: The perspective of experienced psychotherapists" (2015). College of Education Faculty Research and Publications. 385. https://epublications.marquette.edu/edu_fac/385 Authors Clara E. Hill, Yoshi Kanazawa, Sarah Knox, Iris Schauerman, Darren Loureiro, Danielle James, Imani Carter, Shakeena King, Suad Razzak, Melanie Scarff, and Jasmine Moore This article is available at e-Publications@Marquette: https://epublications.marquette.edu/edu_fac/385 Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Education Faculty Research and Publications/College of Education This paper is NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION. Access the published version at the link in the citation below. Psychotherapy Research, Vol. 27, No. 4 (July 2017): 381–396. DOI. This article is © Routledge Taylor & Francis and permission has been granted for this version to appear in e-Publications@Marquette. Routledge Taylor & Francis does not grant permission for this article to be further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without the express permission from Routledge Taylor & Francis.