Tobacco Use Patterns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

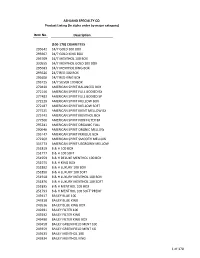

Order Book--7-3-13A.Xlsx

ASHLAND SPECIALTY CO. Product Listing (In alpha order by major category) Item No. Description (100-178) CIGARETTES 295642 24/7 GOLD 100 BOX 295667 24/7 GOLD KING BOX 295709 24/7 MENTHOL 100 BOX 330555 24/7 MENTHOL GOLD 100 BOX 295683 24/7 MENTHOL KING BOX 295626 24/7 RED 100 BOX 295600 24/7 RED KING BOX 295725 24/7 SILVER 100 BOX 279430 AMERICAN SPIRIT BALANCED BOX 272146 AMERICAN SPIRIT FULL BODIED BX 277483 AMERICAN SPIRIT FULL BODIED SP 272229 AMERICAN SPIRIT MELLOW BOX 272187 AMERICAN SPIRIT MELLOW SOFT 277525 AMERICAN SPIRIT MENT MELLOW BX 275743 AMERICAN SPIRIT MENTHOL BOX 277566 AMERICAN SPIRIT NON FILTER BX 293241 AMERICAN SPIRIT ORGANIC FULL 290940 AMERICAN SPIRIT ORGNIC MELLOW 295147 AMERICAN SPIRIT PERIQUE BOX 272260 AMERICAN SPIRIT SMOOTH MELLOW 333773 AMERICAN SPIRIT USGROWN MELLOW 251819 B & H 100 BOX 251777 B & H 100 SOFT 251959 B & H DELUXE MENTHOL 100 BOX 251975 B & H KING BOX 251892 B & H LUXURY 100 BOX 251850 B & H LUXURY 100 SOFT 251918 B & H LUXURY MENTHOL 100 BOX 251876 B & H LUXURY MENTHOL 100 SOFT 251835 B & H MENTHOL 100 BOX 251793 B & H MENTHOL 100 SOFT"PREM" 249417 BAILEY BLUE 100 249318 BAILEY BLUE KING 249516 BAILEY BLUE KING BOX 249391 BAILEY FILTER 100 249292 BAILEY FILTER KING 249490 BAILEY FILTER KING BOX 249458 BAILEY GREEN FIELD MENT 100 249359 BAILEY GREEN FIELD MENT KG 249433 BAILEY MENTHOL 100 249334 BAILEY MENTHOL KING 1 of 170 ASHLAND SPECIALTY CO. Product Listing (In alpha order by major category) Item No. Description 249532 BAILEY MENTHOL KING BOX 249474 BAILEY SKY BLUE 100 249375 BAILEY SKY BLUE -

In Tobacco Use in Kenya

การศึกษาบทบาทของยาสูบไร้ควันเพื่อการควบคุมยาสูบระดับประเทศ และนานาชาติในทศวรรษหน้า รองศาสตราจารย์ ทันตแพทย์วรนัติ วีระประดิษฐ์ รองศาสตราจารย์ทันตแพทย์เชวงเกียรติ แสงศิรินาวิน รองศาสตราจารย์ ทันตแพทย์หญิงเพ็ญพรรณ เลาหพันธ์ ผู้ช่วยศาสตราจารย์ ทันตแพทย์หญิง ดร.วรางคณา ชิดช่วงชัย รองศาสตราจารย์ ทันตแพทย์หญิง ดร.สิริบังอร พิบูลนิยม โขวิฑูรกิจ ทันตแพทย์หญิงวิกุล วิสาลเสสถ์ รองศาสตราจารย์ ทันตแพทย์หญิง ดร.วรานันท์ บัวจีบ การศกษานึ ไดี้ ร้ ับทุนสนับสนนโดยศุ ูนยว์ ิจยและจั ัดการความรู้เพื่อการควบคุมยาสบู (ศจย.) และสํานกงานกองทั นสนุ ับสนุนการสร้างเสริมสขภาพุ (สสส.) สารบญั บทท ี่ หน้า 1 ประวัติของยาสูบไร้ควัน ...................................................................................... 1 1.1 การใช้ยาสูบชนิดเคี้ยว ............................................................................ 1 1.2 การใช้ snuff .......................................................................................... 3 1.3 ทัศนคติ และความเชื่อเกี่ยวกับยาสูบไร้ควัน .......................................... 6 2 การใช้ผลิตภัณฑ์ยาสูบไร้ควัน ............................................................................... 10 2.1 ชนิด ส่วนประกอบ และวิธีการบริโภคผลิตภัณฑ์ยาสูบไร้ควัน .................... 10 2.2 การผลิต การบริโภค และความชุกของการใช้ผลิตภัณฑ์ยาสูบไร้ควัน .... 20 2.3 ความสัมพนธั ์ระหว่างการใช้ยาสูบไร้ควันและการสูบบุหรี่ ..................... 43 2.4 สรุป ........................................................................................................ 55 3 ผลของยาสูบไร้ควันต่อสุขภาพ ............................................................................ -

The Acrylamide Content of Smokeless Tobacco Products Kevin Mcadam1*, Harriet Kimpton1, Carl Vas1, David Rushforth1, Andrew Porter2 and Brad Rodu3

McAdam et al. Chemistry Central Journal (2015) 9:56 DOI 10.1186/s13065-015-0132-1 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access The acrylamide content of smokeless tobacco products Kevin McAdam1*, Harriet Kimpton1, Carl Vas1, David Rushforth1, Andrew Porter2 and Brad Rodu3 Abstract Background: There is considerable interest from a regulatory and public health perspective in harmful and poten- tially harmful constituents in tobacco products, including smokeless tobacco products (STPs). A wide range of com- mercial STPs from the US and Sweden, representing 80–90 % of the 2010 market share for all the major STP categories in these two countries, were analysed for the IARC Group 2A carcinogen acrylamide. These STPs comprised the follow- ing styles: Swedish loose and portion snus, US snus, chewing tobacco, moist snuff, dry snuff, soft pellet, hard pellet and plug. Results: Acrylamide was detected in all the products tested and quantified in all but one product. Concentrations ranged from 62 to 666 ng/g wet weight basis (WWB). The average levels of acrylamide (WWB) by type of STP were not significantly different (p > 0.05) except for US snus which had, on average, greater levels but with a very wide range of individual levels according to the manufacturer. Acrylamide levels in STPs were significantly and positively correlated with pH, but not with levels of either reducing sugars or ammonia nitrogen. Levels of acrylamide increased by sixfold or more (on a dry weight basis) during manufacture of a snus sample and then decreased during subsequent storage for up to 22 weeks. Acrylamide generation in tobacco generally appears to occur at lower temperatures, but longer time scales than found with food production. -

Campbell Wholesale Company, Inc. Order Book 6849 E

Campbell Wholesale Company, Inc. Order Book 6849 E. 13th 1104 W. Broadway Tulsa, Oklahoma 74112 Muskogee, Oklahoma 74401 1(800) 722-2359 1(888) 516-2997 (918) 836-8774 (918) 682-6608 Fax: (918) 832-5689 Fax: (918) 686-8182 Customer No.: ________________________________________________ Customer Name: _____________________________________________ Date: _________________________________________________________ Written By: ___________________________________________________ ITEM NO. QTY. DESCRIPTION ITEM NO. QTY. DESCRIPTION _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ -

Supplementary Table 2. Leading Brands by Product Type in Alphabetical Order

Supplementary material Tob Control Supplementary Table 2. Leading brands by product type in alphabetical order. E-cigarettes1 Hookah2 Cigar3 Cigarette4 Smokeless5 n = 35 n = 13 n = 24 n = 22 n = 18 21st Century Smoke Al Amir 305'S 305's Beech nut Artery Al Fakher Arturo Fuente Basic Camel Aspire Fantasia Backwoods Camel Copenhagen AugVape Fumari Captain Black Doral General Green Smoke Havana Cheyenne Eagle Grizzly JAK Layalina Davidoff Grand Prix Husky Joyetech Nakhla Djarum Kool Kayak Justfog Starbuzz Dutch Masters L&M Kodiak JUUL Social Smoke Dutch Treats Liggett Select Levi Garrett KangerTech Sultan Garcia y Vega Marlboro Longhorn Logic Tangiers Hoyo de Monterray Maverick Marlboro Lost vape Tonic La Gloria Cumbana Purito Misty Red Man MarkTen Macunado Natural American Spirit Red Seal Mistic Middleton's Black and Mild Newport Skoal My Blu Montecristo Pall Mall Starr MYLÉ Optimo Parliament Stoker's NJOY Partagas Pyramid Timber wolf SMOK Phillies Salem ZYN Sigelei Punch Sonoma SnowWolf Romeo y Julieta USA gold Suorin Swisher Sweets Virginia Slims Uwell Talon Winston Vandy Vape White Owl Vapeccino Winchester VAPIN PLUS Vaporesso VUSE VOOPOO WISMEC Wotofo Note. We identified the above brands using the following sources, including Nielsen Scantrack data on top brands for each product type based on July 2017-June 2018 dollar sales for total U.S. convenience stores and all outlets combined. The method section of the manuscript provides further information on data sources. E-cigarette: 12 brands from Nielsen, 4 from Euromonitor, 16 from leading online retailers identified by ECigIntelligence and Google Trends, and 3 from Google Trends alone. Hookah: 1 brand from Nielsen and 12 listed by adult users who reported having a regular brand in Wave 4 of PATH. -

Reynolds American Names New Chief Executives for Its Conwood and Santa Fe Natural Tobacco Company Subsidiaries

Reynolds American Inc. P.O. Box 2990 Winston-Salem, NC 27102-2990 Reynolds American names new chief executives for its Conwood and Santa Fe Natural Tobacco Company subsidiaries WINSTON-SALEM, N.C. – Dec. 9, 2008 -- Reynolds American Inc. (NYSE: RAI) today announced the appointment of new chief executive officers for the company’s Conwood Company, LLC and Santa Fe Natural Tobacco Company, Inc. subsidiaries. The current chief executives of those two subsidiaries plan to retire in 2009. Bryan K. Stockdale, 50, has been named president and CEO of Conwood, the nation’s second-largest smokeless tobacco manufacturer, effective Feb. 1, 2009. Stockdale will succeed William M. Rosson, 60, who plans to retire after 34 years of service at Conwood. Stockdale is currently senior vice president of marketing operations for R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, Reynolds American’s largest subsidiary, and has worked for that company for 30 years. Rosson will remain with Conwood in an advisory role for a period of time after Stockdale joins the company to ensure a smooth transition. Nicholas A. Bumbacco, 44, has been named president and CEO of Santa Fe Natural Tobacco Co., effective March 1, 2009. Bumbacco will replace Richard M. Sanders, 55, who plans to remain in an advisory transition position before retiring with 32 years of service on July 1, 2009. Bumbacco is currently president and CEO of RAI’s R.J. Reynolds Global Products, Inc. subsidiary. Bumbacco has 20 years of experience in the global tobacco industry. RAI will be transitioning the lines of business formerly managed by R.J. Reynolds Global Products to other RAI subsidiaries, so no successor to Bumbacco in his previous position will be named. -

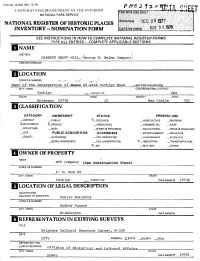

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 (Rav. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS | NAME HISTORIC GARRETT SNUFF MILL,/George W. Helme Company] AND/PR COMMON LOCATION STREET& NUMBER vfctf f) [• CW « t vEast of the intersection of Rea-fee 82-with Yorklyn Road —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Yorklyn ' _ VICINITY OF One STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Delaware 19736 10 New Castle 002 |f CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _JDISTRICT _PUBLIC X— OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X-BUILDING(S) X-PRIVATE —.UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL _ PARK __STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE __SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS — YES: RESTRICTED _ GOVERNMENT _ SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED —YES: UNRESTRICTED X— INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION X— NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME NVF Company (See continuation Sheet) STREET & NUMBER P. 0. BOX 68 CITY, TOWN STATE Yorklyn _ VICINITY OF Delaware 19736 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. Public Building STREET & NUMBER Rodney Square CITY, TOWN STATE WiImington Delaware REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Delaware Cultural Resource Survey, W-329 DATE 1975 —FEDERAL X-STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR ____________mvisionSURVEY RECORDS rH vn c^ «„ of^f HistoricalTT • ^ and Cultural Affairs CITY, TOWN STATE Dover Delaware 19901 DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X—ORIGINALSITE —GOOD _RUINS ^.ALTERED .MOVFD DATF X_FAIR —UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN! PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Garrett Snuff Mills are Delaware's most architecturally unified complex of nineteenth-century industrial structures still in use. -

NHANES 2005 TOBACCO – SMQ Target Group

NHANES 2005 TOBACCO – SMQ Target Group: SPs 12-19 (Audio-CASI) SMQ.620_ The following questions are about cigarette smoking and other tobacco use. SMQ.620 Have you ever tried cigarette smoking, even 1 or 2 puffs? INSTRUCTIONS TO SP: Please select . Yes ................................................................ 1 No.................................................................. 2 (SMQ.680) REFUSED ..................................................... 7 (SMQ.680) DON'T KNOW ............................................... 9 (SMQ.680) SMQ.630 How old were you when you smoked a whole cigarette for the first time? SMQ.630a INSTRUCTIONS TO SP: Please enter an age or select zero for never smoked a whole cigarette. CAPI INSTRUCTION: COMBINATION CONTROL: Number Pad: Enter Age ACCEPTABLE VALUES: 0, 6-20 years, Refused, Don’t Know. If R enters 0, store 55 for "Never smoked a whole cigarette.” If R enters 1-5, store 6 years. HARD EDIT: If SMQ.630 > RIAAGEYR then ERROR Error message: "Your response is older than your recorded age. Please press the “Back” button, press “Clear,” and try again." |___|___| ENTER AGE AGE............................................................... 1-20 NEVER SMOKED A WHOLE CIGARETTE... 55 (SMQ.680) REFUSED ..................................................... 77 (SMQ.680) DON'T KNOW ............................................... 99 (SMQ.680) FSQ-5 SMQ.640 During the past 30 days, on how many days did you smoke cigarettes? INSTRUCTIONS TO SP: Please enter a number or enter zero if none. CAPI INSTRUCTION: ACCEPTABLE VALUES: 0-30, Refused, Don’t Know HARD EDIT: If SMQ.640 > 30 then ERROR Error message: "Your response cannot exceed 30 days. Please press the “Back” button, press “Clear,” and try again." |___|___| ENTER NUMBER OF DAYS REFUSED ..................................................... 77 (SMQ.670) DON'T KNOW .............................................. -

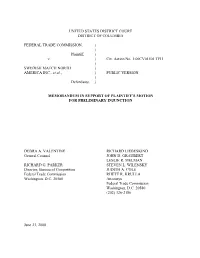

Memorandum in Support of Plaintiff's Motion

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION, ) ) Plaintiff, ) v. ) Civ. Action No. 1:00CV01501 TFH ) SWEDISH MATCH NORTH ) AMERICA INC., et al., ) PUBLIC VERSION ) Defendants. ) MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFF’S MOTION FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION DEBRA A. VALENTINE RICHARD LIEBESKIND General Counsel JOHN D. GRAUBERT LESLIE R. MELMAN RICHARD G. PARKER STEVEN L. WILENSKY Director, Bureau of Competition JUDITH A. COLE Federal Trade Commission RHETT R. KRULLA Washington, D.C. 20580 Attorneys Federal Trade Commission Washington, D.C. 20580 (202) 326-2186 June 23, 2000 Table of Contents Table of Authorities ......................................................... iii Introduction and Summary .................................................... 1 Argument ................................................................. 5 I. SECTION 13(b) OF THE FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION ACT ESTABLISHES A PUBLIC INTEREST STANDARD FOR GRANTING INJUNCTIVE RELIEF ...... 5 II. THE PROPOSED ACQUISITION VIOLATES THE ANTITRUST LAWS. ............ 7 A. Loose Leaf Chewing Tobacco Is a Relevant Product Market. .................. 8 1. Loose Leaf Chewing Tobacco Is a Unique Product ................... 11 2. The Defendants Themselves Recognize that Loose Leaf Chewing Tobacco Constitutes a Distinct Product Market. ......................... 12 3. The Evidence Shows that Loose Leaf Tobacco Is a Distinct Market from Moist Snuff .............................................. 15 a. Industry and Public Recognition of the Market ................ 15 -

E-Cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults: a Report of the Surgeon General

E-Cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General 2016 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Public Health Service Office of the Surgeon General Rockville, MD National Library of Medicine Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: United States. Public Health Service. Office of the Surgeon General, issuing body. | National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (U.S.). Office on Smoking and Health, issuing body. Title: E-cigarette use among youth and young adults : a report of the Surgeon General. Description: Atlanta, GA : U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: MESH: Electronic Cigarettes – utilization. | Smoking – adverse effects. | Electronic Cigarettes – adverse effects. | Tobacco Industry. | Young Adult. | Adolescent. | United States. Classification: NLM QV 137 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Office on Smoking and Health For more information For more information about the Surgeon General’s report, visit www.surgeongeneral.gov. To download copies of this document, go to www.cdc.gov/tobacco. To order copies of this document, go to www.cdc.gov/tobacco and click on Publications Catalog or call 1-800-CDC-INFO (1-800-232-4636); TTY: 1-888-232-6348. Suggested Citation U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. E-Cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. -

Creative Data Research (Page 1) Date: ___/___/___ Sold To: ______Cust No: ______

Creative Data Research (Page 1) Date: ___/___/___ Sold To: ________________________________________ Cust No: ______________ CIGARETTES * REGULARS 70MM F/P (1) CIGARETTES * KING SIZE 85MM F/P (2) 100100 _____ CAMEL NON-FILTER 111750 _____ MARLBORO MENTHOL KING 100250 _____ LUCKY STRIKE REGULAR 111780 _____ MARLBORO MENTHOL BOX KING 100270 _____ MARLBORO MENTHOL 72MM BLUE BOX 111788 _____ MARLBORO SMOOTH BOX KING 100280 _____ MARLBORO MENTHOL 72MM GREEN BOX 111800 _____ MARLBORO LIGHT KING 100290 _____ MARLBORO RED 72MM BOX 111850 _____ MARLBORO LIGHT BOX 100300 _____ MARLBORO LIGHTS 72MM BOX 111854 _____ MARLBORO LT MENTHOL SOFT KING 100310 _____ MARLBORO ULTRA LIGHT 72MM BOX 111855 _____ MARLBORO LT MTHL BOX KING 111865 _____ MARLBORO ULTRA LIGHT BOX KING CIGARETTES * KING SIZE 85MM F/P (2) 111872 _____ MARLBORO ULTRA LT MENTHOL BOX KING 100430 _____ AMERICAN SPIRIT REG/FILTER SOFT 111880 _____ MARLBORO VIRGINIA BLEND BOX KING 100440 _____ AMERICAN SPIRIT REG/FILTER BOX 111890 _____ MERIT BOX KING 100450 _____ AMERICAN SPIRIT MED/FILTER BOX 111900 _____ MERIT LIGHT KING 100460 _____ AMERICAN SPIRIT LIGHT FILTER SOFT 111950 _____ MERIT MENTHOL KING 100470 _____ AMERICAN SPIRIT LIGHT FILTER BOX 111960 _____ MERIT ULTIMA SOFT KING 100476 _____ AMERICAN SPIRIT ULT LT BOX KING 111970 _____ MERIT ULTIMA BOX KING 100478 _____ AMERICAN SPIRIT FF MENTHOL BOX 112000 _____ MERIT ULTRA LIGHT KING 100480 _____ AMERICAN SPIRIT MTHL LIGHT BOX 112010 _____ MERIT ULTRA LT BOX KING 100490 _____ AMERICAN SPIRIT NON-FILTER KING 112050 _____ MERIT ULTRA LT -

Oregon's Directory of Smokeless Tobacco Brands Approved for Stamping and Sale

ALPHABETICAL BRAND LIST The following is Oregon’s Directory of Smokeless Tobacco Brands Approved for Stamping and Sale in alphabetical order. The List is divided into three Sections: First Section – Deletions to the List in the Last 30 Days Second Section – Additions to the List in the Last 30 Days Third Section – Main List That Reflects Current Status UPDATED September 16, 2021 DM #7268435 BRAND - Deletions to the List Manufacturer NPM Product Initial in the Last 30 Days /PM Certified Date BRAND - Additions to the List Manufacturer NPM Product Initial in the Last 30 Days /PM Certified Date Cougar - Fine Cut Natural 1.2 oz. American Snuff Company, LLC Moist 8/18/2021 Puck Snuff Cougar - Long Cut Straight 1.2 oz. American Snuff Company, LLC Moist 8/18/2021 Puck Snuff Cougar - Long Cut Wintergreen 1.2 American Snuff Company, LLC Moist 8/18/2021 oz. Puck Snuff Grizzly - Snus Artic Blue .53 oz. Tin American Snuff Company, LLC Moist 9/16/2021 Snuff Grizzly - Snus Natural .53 oz. Tin American Snuff Company, LLC Moist 9/16/2021 Snuff Grizzly - Snus Wintergreen .53 oz. American Snuff Company, LLC Moist 9/16/2021 Tin Snuff Kodiak - Premium Natural 1.2 oz. American Snuff Company, LLC Moist 8/18/2021 Puck Snuff Kodiak - Premium Natural Extra American Snuff Company, LLC Moist 8/18/2021 Long Cut 1.2 oz. Puck Snuff Kodiak - Premium Natural Fine Cut American Snuff Company, LLC Moist 8/18/2021 1.2 oz. Puck Snuff Kodiak - Premium Natural Long Cut American Snuff Company, LLC Moist 8/18/2021 1.2 oz.