Tate Modern a Year of Sweet Success

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CAN ART HISTORY DIGEST NET ART? Julian Stallabrass from Its

165 CAN ART HISTORY DIGEST NET ART? Julian Stallabrass From its beginnings, Internet art has had an uneven and confl icted relation- ship with the established art world. There was a point, at the height of the dot-com boom, when it came close to being the “next big thing,” and was certainly seen as a way to reach new audiences (while conveniently creaming off sponsorship funds from the cash-rich computer companies). When the boom became a crash, many art institutions forgot about online art, or at least scaled back and ghettoized their programs, and that forgetting became deeper and more widespread with the precipitate rise of con- temporary art prices, as the gilded object once more stepped to the forefront of art-world attention. Perhaps, too, the neglect was furthered by much Internet art’s association with radical politics and the methods of tactical media, and by the extraordinary growth of popular cultural participation online, which threatened to bury any identifi ably art-like activity in a glut of appropriation, pastiche, and more or less knowing trivia. One way to try to grasp the complicated relation between the two realms is to look at the deep incompatibilities of art history and Internet art. Art history—above all, in the paradox of an art history of the contemporary— is still one of the necessary conduits through which works must pass as they move through the market and into the security of the museum. In examining this relation, at fi rst sight, it is the antagonisms that stand out. Lacking a medium, eschewing beauty, confi ned to the screen of the spreadsheet and the word processor, and apparently adhering to a discred- ited avant-gardism, Internet art was easy to dismiss. -

WES HILL Hipster Aesthetics: Creatives with No Alternative

Wes Hill, Hipster Aesthetics: Creatives with no alternative WES HILL Hipster Aesthetics: Creatives with no alternative ABSTRACT What is a hipster, and why has this cultural trope become so resonant of a particular mode of artistic and connoisseurial expression in recent times? Evolving from its beatnik origins, the stereotypical hipster today is likely to be a globally aware “creative” who nonetheless fails in their endeavour to be an exemplar of progressive cultural taste in an era when cultural value is heavily politicised. Today, artist memes and hipster memes are almost interchangeable, associated with people who are desperate to be fashionably distinctive, culturally literate or as having discovered some obscure cultural phenomenon before anyone else. But how did we arrive at this situation where elitist and generically “arty” connotations are perceived in so many cultural forms? This article will attempt to provide an historical context to the rise of the contemporary, post-1990s, hipster, who emerged out of the creative and entrepreneurial ideologies of the digital age – a time when artistic creations lose their alternative credence in the markets of the creative industries. Towards the end of the article “hipster hate” will be examined in relation to post- critical practice, in which the critical, exclusive, and in-the-know stances of cultural connoisseurs are thought to be in conflict with pluralist ideology. Hipster Aesthetics: Creatives with no alternative Although the hipster trope is immediately recognisable, it has been allied with a remarkable diversity of styles, objects and activities over the last two decades, warranting definition more in terms of the attempt to promote counter-mainstream sensibilities than pertaining to a specific aesthetic as such. -

Michael Landy Selected Biography Born in London, 1963 Lives And

Michael Landy Selected Biography Born in London, 1963 Lives and works in London, UK 1985-88, Goldsmith's College Solo Exhibitions 2015 Breaking News, Galerie Sabine Knust, Munich, Germany 2014 Saints Alive, Antiguo Colegio de San Ildefonso, Mexico City, Mexico 2013 20 Years of Pressing Hard, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK Saints Alive, National Gallery, London, UK Michael Landy: Four Walls, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, UK 2011 Acts of Kindness, Kaldor Public Art Projects, Sydney, Australia Acts of Kindness, Art on the Underground, London, UK Art World Portraits, National Portrait Gallery, London, UK 2010 Art Bin, South London Gallery, London, UK 2009 Theatre of Junk, Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris, France 2008 Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK In your face, Galerie Paul Andriesse, Amsterdam Three-piece, Sabine Knust, Munich, Germany 2007 Man in Oxford is Auto-destructive, Sherman Galleries, Sydney, Australia H.2.N.Y, Alexander and Bonin, New York 2004 Welcome To My World built with you in mind, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK Semi-detached, Tate Britain, London, UK 2003 Nourishment, Sabine Knust/Maximilianverlag, Munich, Germany 2002 Nourishment, Maureen Paley/Interim Art, London, UK 2001 Break Down, C&A Store, Marble Arch, London, UK 2000 Handjobs (with Gillian Wearing), Approach Gallery, London, UK 1999 Michael Landy at Home, 7 Fashion Street, London, UK 1996 The Making of Scrapheap Services, Waddington Galleries, London, UK Scrapheap Services, Chisenhale Gallery, London; Electric Press Building, Leeds, UK (organised by the HenryMoore -

You Cannot Be Serious: the Conceptual Innovator As Trickster

This PDF is a selection from a published volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Conceptual Revolutions in Twentieth-Century Art Volume Author/Editor: David W. Galenson Volume Publisher: Cambridge University Press Volume ISBN: 978-0-521-11232-1 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/gale08-1 Publication Date: October 2009 Title: You Cannot be Serious: The Conceptual Innovator as Trickster Author: David W. Galenson URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c5791 Chapter 8: You Cannot be Serious: The Conceptual Innovator as Trickster The Accusation The artist does not say today, “Come and see faultless work,” but “Come and see sincere work.” Edouard Manet, 18671 When Edouard Manet exhibited Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe at the Salon des Refusés in 1863, the critic Louis Etienne described the painting as an “unbecoming rebus,” and denounced it as “a young man’s practical joke, a shameful open sore not worth exhibiting this way.”2 Two years later, when Manet’s Olympia was shown at the Salon, the critic Félix Jahyer wrote that the painting was indecent, and declared that “I cannot take this painter’s intentions seriously.” The critic Ernest Fillonneau claimed this reaction was a common one, for “an epidemic of crazy laughter prevails... in front of the canvases by Manet.” Another critic, Jules Clarétie, described Manet’s two paintings at the Salon as “challenges hurled at the public, mockeries or parodies, how can one tell?”3 In his review of the Salon, the critic Théophile Gautier concluded his condemnation of Manet’s paintings by remarking that “Here there is nothing, we are sorry to say, but the desire to attract attention at any price.”4 The most decisive rejection of these charges against Manet was made in a series of articles published in 1866-67 by the young critic and writer Emile Zola. -

British Art Studies July 2016 British Sculpture Abroad, 1945 – 2000

British Art Studies July 2016 British Sculpture Abroad, 1945 – 2000 Edited by Penelope Curtis and Martina Droth British Art Studies Issue 3, published 4 July 2016 British Sculpture Abroad, 1945 – 2000 Edited by Penelope Curtis and Martina Droth Cover image: Installation View, Simon Starling, Project for a Masquerade (Hiroshima), 2010–11, 16 mm film transferred to digital (25 minutes, 45 seconds), wooden masks, cast bronze masks, bowler hat, metals stands, suspended mirror, suspended screen, HD projector, media player, and speakers. Dimensions variable. Digital image courtesy of the artist PDF generated on 21 July 2021 Note: British Art Studies is a digital publication and intended to be experienced online and referenced digitally. PDFs are provided for ease of reading offline. Please do not reference the PDF in academic citations: we recommend the use of DOIs (digital object identifiers) provided within the online article. Theseunique alphanumeric strings identify content and provide a persistent link to a location on the internet. A DOI is guaranteed never to change, so you can use it to link permanently to electronic documents with confidence. Published by: Paul Mellon Centre 16 Bedford Square London, WC1B 3JA https://www.paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk In partnership with: Yale Center for British Art 1080 Chapel Street New Haven, Connecticut https://britishart.yale.edu ISSN: 2058-5462 DOI: 10.17658/issn.2058-5462 URL: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk Editorial team: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/editorial-team Advisory board: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/advisory-board Produced in the United Kingdom. A joint publication by Contents Sensational Cities, John J. -

Sarah Lucas (B.1962) Self-Portraits 1990–98

Sarah Lucas (b.1962) Self-Portraits 1990–98 Key Facts: • Medium: Iris print • Size: 12 prints, dimensions variable (height: 78–98 cm; width: 72–90 cm) • Collection: British Council Collection 1. ART HISTORICAL TERMS AND CONCEPTS Visual analysis: The series comprises a mixture of black-and-white, colour and collaged photographs. The artist is the subject of each image, though her appearance varies greatly. Art History in Schools CIO | Registered Charity No. 1164651 | www.arthistoryinschools.org.uk In the majority, we see Lucas’ face looking out as us from behind a dark curtain of hair. Provocative or arresting, she challenges us to return her gaze. In other photographs, she is engaged in an activity, smoking and/or on top of, or sandwiched between, a toilet. Neither type presents her in a light we might expect from a female artist; rather, her unflinching gaze and androgynous appearance suggest that gender is something fluid and up for question. One photograph stands apart from others in the series: entitled Summer (1998), it depicts liquid being thrown at Lucas’ face. The fluid distorts Lucas’ features and causes her to look away from the lens. In many of the photographs, additional objects add humour and interest: a skull, fried eggs, knickers, a large fish, a mug of tea, a banana. Together with Lucas’ candid postures, sexual puns are made more apparent and the objects themselves become symbolic. Lucas’ legs spread wide and ending in heavy-duty boots are often photographed from below, with this view enhancing our impression of them as strong and dominant. The photographs are both a retort to the laddish culture of 1990s Britain and a reflection of the growth of the ‘ladette’. -

Young British Artists: the Legendary Group

Young British Artists: The Legendary Group Given the current hype surrounding new British art, it is hard to imagine that the audience for contemporary art was relatively small until only two decades ago. Predominantly conservative tastes across the country had led to instances of open hostility towards contemporary art. For example, the public and the media were outraged in 1976 when they learned that the Tate Gallery had acquired Carl Andre’s Equivalent VIII (the bricks) . Lagging behind the international contemporary art scene, Britain was described as ‘a cultural backwater’ by art critic Sarah Kent. 1 A number of significant British artists, such as Tony Cragg, and Gilbert and George, had to build their reputation abroad before being taken seriously at home. Tomake matters worse, the 1980s saw severe cutbacks in public funding for the arts and for individual artists. Furthermore, the art market was hit by the economic recession in 1989. For the thousands of art school students completing their degrees around that time, career prospects did not look promising. Yet ironically, it was the worrying economic situation, and the relative indifference to contemporary art practice in Britain, that were to prove ideal conditions for the emergence of ‘Young British Art’. Emergence of YBAs In 1988, in the lead-up to the recession, a number of fine art students from Goldsmiths College, London, decided it was time to be proactive instead of waiting for the dealers to call. Seizing the initiative, these aspiring young artists started to curate their own shows, in vacant offices and industrial buildings. The most famous of these was Freeze ; and those who took part would, in retrospect, be recognised as the first group of Young British Artists, or YBAs. -

Boston University Study Abroad London Modern British Art and Design CAS AH 320 (Core Course) Spring 2016

Boston University Study Abroad London Modern British Art and Design CAS AH 320 (Core course) Spring 2016 Instructor Information A. Name Dr Caroline Donnellan B. Day & Time Wednesday & Thursdays, 9.00am–1.00pm commencing Thursday 14 January 2016 C. Contact Hours 40 + 2 hour exam on Monday 15 February 2016 D. Location Brompton Room, 43 Harrington Gardens & Field Trips E. BU Telephone 020 7244 6255 F. Email [email protected] G. Office hours By appointment Course Overview This is the Core Class for the Arts & Administration Track and is designed as an introduction to modern art and design in Britain. This course draws from London’s rich permanent collections and vibrant modern art scene which is constantly changing, the topics to be discussed are as follows: ‘Artist and Empire: Facing Britain’s Imperial Past’ at Tate Britain (Temporary Exhibition: 25 Nov 2015–10 Apr 2016); Early Modern Foreign Art in London at the National Gallery (Permanent Collection); British Collectors at the Courtauld Gallery (Permanent Collection); London Art Fair 28th edition (Temporary Exhibition 20 Jan–24 Jan 2016) Exhibiting War at the Imperial War Museum (Permanent Collection); ‘Painting the Modern Garden: Monet to Matisse’ at the Royal Academy of Arts (Temporary Exhibition: 30 Jan 2016–20 Apr 2016) ‘Alexander Calder: Performing Sculpture’ at Tate Modern (Temporary Exhibition: 11 Nov 2015–3 Apr 2016) Newport Street Gallery: ‘John Hoyland Power Stations Paintings 1964-1982’ (Temporary Exhibition: 8 Oct 2015-3 April 2016) London Art Market (II) at the Saatchi Gallery ‘Champagne Life’ (Temporary Exhibition: 13 Jan 2016–6 Mar 2016) + ‘Aidan Salakhova: Revelations’ (Temporary Exhibition: 13 Jan 2016–28 Feb 2016) Bermondsey White Cube London Art Market (I): ‘Gilbert & George The Banners’ (Temporary Exhibition: 25 Nov 2015–24 Jan 2016) Teaching Pattern Teaching Sessions will be divided between classroom lectures and field trips – where it is not possible to attend as a group these will be self-guided. -

Summer 2016 British Sculpture Abroad

British Art Studies Issue 3 – Summer 2016 British Sculpture Abroad, 1945 – 2000 British Art Studies Issue 3, published 4 July 2016 British Sculpture Abroad, 1945 – 2000 Special issue edited by Penelope Curtis and Martina Droth www.britishartstudies.ac.uk Cover image: Simon Starling, Project for a Masquerade (Hiroshima) (film still), 2010–11. 16 mm film transferred to digital (25 minutes, 45 seconds), wooden masks, cast bronze masks, bowler hat, metals stands, suspended mirror, suspended screen, HD projector, media player, and speakers. Dimensions variable. Digital image courtesy of the artist PDF produced on 9 Sep 2016 Note: British Art Studies is a digital publication and intended to be experienced online and referenced digitally. PDFs are provided for ease of reading offline. Please do not reference the PDF in academic citations: we recommend the use of DOIs (digital object identifiers) provided within the online article. These unique alphanumeric strings identify content and provide a persistent link to a location on the internet. A DOI is guaranteed never to change, so you can use it to link permanently to electronic documents with confidence. Published by: Paul Mellon Centre 16 Bedford Square London, WC1B 3JA http://www.paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk In partnership with: Yale Center for British Art 1080 Chapel Street New Haven, Connecticut http://britishart.yale.edu ISSN: 2058-5462 DOI: 10.17658/issn.2058-5462 URL: http://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk Editorial team: http://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/editorial-team Advisory board: http://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/advisory-board Produced in the United Kingdom. Britishness, Identity, and the Three-Dimensional: British Sculpture Abroad in the 1990s Essay by Courtney J. -

Branding of the Museum

The Branding of the Museum Julian Stallabrass [‘Brand Strategy of Art Museum’, in Wang Chunchen, ed., University and Art Museum, Tongji University Press, Shanghai 2011, published in Chinese. Also published in Cornelia Klinger, ed., Blindheit und Hellsichtigkeit: Künstlerkritik an Politik und Gesellschaft der Gegenwart, Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2013, pp. 303-16; and in a revised and updated version as ‘The Branding of the Museum’, Art History, vol. 37, no. 1, February 2014, pp. 148-65.] The British Museum shop, 2008. Photo: JS While museums have long had names, identities and even logos, their explicit branding by specialist companies devoted to such tasks is relatively new.1 The brand is an attempt to 1 This piece has had a long gestation, and has benefitted from the comments of many participants at lectures and symposia. As a talk, it was first given at the CIMAM 2006 Annual Conference, Contemporary Institutions: Between Public and Private, held at Tate Modern. In the large literature about museums and their changing roles, there has slowly begun to emerge some consideration of branding. Margot A. Wallace, Museum Branding: How to Create and Maintain Image, Loyalty and Support, AltaMira Press, Oxford 2006 is, as its title suggests, a how-to guide. James B. Twitchell, Branded Nation: The Marketing of Megachurch, College Inc. and Museumworld, Simon & Schuster, New York 2004 is a jocular lament about the pervasiveness of marketing culture, which sees the museum, too simply, as providing ‘edutainment’ with no meaningful differentiation from consumer culture. More seriously, Andrew Dewdney/ David Bibosa/ Victoria Walsh, Post-Critical Museology: Theory and Practice in Stallabrass, Branding, p. -

1 SIMON PATTERSON 1967 Born in England. 1985-86 Hertfordshire

SIMON PATTERSON 1967 Born in England. 1985-86 Hertfordshire College of Art and Design, St. Albans. 1986-89 Goldsmiths' College, London, BA Fine Art. Lives and works in London SOLO EXHIBITIONS 1989 "Simon Patterson", Third Eye Centre, Glasgow. 1991 "Allahu Akbar", Riverside Studios, London. 1993 "Monkey Business", The Grey Art Gallery, New York. 1994 "General Assembly", Chisenhale Gallery, London (exh. cat.) "Simon Patterson", Kluuvin Gallery, Helsinki. "General Assembly", Angel Row Gallery, Nottingham. 1995 "Simon Patterson", Gandy Gallery, Prague. "Sister Ships", The Customs House, South Shields. "Midway", Artium, Fukuoka. "Simon Patterson", Röntgen Kunstinstitut, Tokyo. "Simon Patterson", Kohji Ogura Gallery, Nagoya. 1996 "Simon Patterson", Lisson Gallery, London. "Simon Patterson", MCA, Chicago. 1997 "Simon Patterson", Röntgen Kunstraum, Tokyo. “Wall Drawings”, Kunsthaus Zürich. "Simon Patterson - Spies", Gandy Gallery, Prague. 1998 "Name Paintings", Kohji Ogura Gallery, Nagoya. "Simon Patterson", Yamaguchi Gallery, Osaka. "New Work", Röntgen Kunstraum,Tokyo. "Simon Patterson", Mitaka City Art Center, Tokyo. 1999 “Simon Patterson”, Magazin 4, Bregenz. 2000 “Manned Flight, 1999-”, Fig 1, London. “Simon Patterson”, VTO Gallery, London. 2001 “Manned Flight”, Lille. “Le Match des couleurs’, artconnexion, Lille. “Simon Patterson”, Sies+Hoeke Galerie, Düsseldorf. 2002 “Manned Flight, 1999—”, Studio 12, ARTSPACE, Sydney. 2003 “Simon Patterson - Midway”, Roentgenwerke, Tokyo. 2004 “Simon Patterson - Escape Routine”, Roentgenwerke, Tokyo. “Simon Patterson - 24 hours”, Roentgenwerke, Tokyo. “Simon Patterson - New Work”, Roentgenwerke, Tokyo. “Domini Canes - Hounds of God”, Lowood Gallery and Kennels, Armathwaite, Cumbria. (exh cat.) “PaintstenroomS”, gSM, London. 2005 “High Noon”, Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh. (exh. cat.) “High Noon”, Ikon Gallery Birmingham. (exh cat.) 2006 “Black-list”, Haunch of Venison, Zürich.(exh. cat.) 2007 “Black-list”, Haunch of Venison, London. -

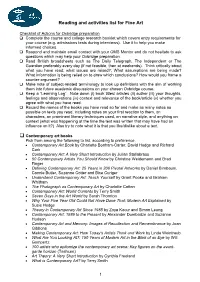

Fine Art Reading List

Reading and activities list for Fine Art Checklist of Actions for Oxbridge preparation Complete the course and college research booklet which covers entry requirements for your course (e.g. admissions tests during interviews). Use it to help you make informed choices. Respond and maintain email contact with your OMS Mentor and do not hesitate to ask questions which may help your Oxbridge preparation. Read British broadsheets such as The Daily Telegraph, The Independent or The Guardian preferably every day (if not feasible, then at weekends). Think critically about what you have read; what issues are raised?; What assumptions are being made? What information is being relied on to draw which conclusions? How would you frame a counter-argument? Make note of subject-related terminology to look up definitions with the aim of working them into future academic discussions on your chosen Oxbridge course. Keep a “Learning Log”. Note down (i) book titles/ articles (ii) author (iii) your thoughts, feelings and observations (iv) context and relevance of the book/article (v) whether you agree with what you have read. Record the names of the books you have read so far and make as many notes as possible on texts you read, including notes on your first reaction to them, on characters, on prominent literary techniques used, on narrative style, and anything on context (what was happening at the time the text was written that may have had an influence on it?) Also try to note what it is that you like/dislike about a text. Contemporary art books Pick from among the following to list, according to preference.