PDF 194.41 Kb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book Review of Almost Human, the Astonishing Tale of Homo Naledi and the Discovery That Changed Our Human Story, by Lee Berger and John Hawks

Answers Research Journal 10 (2017):187–194. www.answersingenesis.org/arj/v10/book_review_almost_human.pdf Book Review of Almost Human, the Astonishing Tale of Homo naledi and the Discovery that Changed our Human Story, by Lee Berger and John Hawks Jean O’Micks, Independent Scholar. Timothy L. Clarey, Institute for Creation Research, 1806 Royal Lane, Dallas, Texas 75229 Abstract Lee Berger’s 2017 book Almost Human is a recount of his lifetime quest to find human ancestors. We review the four main sections of this book starting with his first trip to Tanzania at age 24, his involvement in the H. floresiensis controversy, then his finding of Australopithecus sediba and his latest discovery in South Africa of Homo naledi. It is interesting to read how Berger and his colleagues debated their decision to put A. sediba into the genus Australopithecus and did not succumb to evolutionary biases and claim the fossils belong to the genus Homo. The main thrust of this book seems to culminate in in the final two sections where Berger describes in detail the discovery process and the difficulties involved in excavation of H. naledi from a near inaccessible cave, dubbed the Dinaledi Chamber. His initial reactions to seeing the first bones from the site are most telling, describing in several passages how similar the anatomy of the fossils was to an australopith, and unlike a human. And yet, he eventually concludes that these fossils represented a hominin that was “almost human,” classifying it as a member of the genus Homo. Berger also reveals a few facts that were left out of the many papers published on H. -

Fy2015 Perot Museum Impact Report

Together, we will embolden young minds to become the explorers, innovators and problem-solvers for the next generation. 4 REAL SCIENCE 10 INCREASING ACCESS AND DEEPENING COMMUNITY IMPACT 12 FINANCIAL AID 14 FY15 STATS: BUILDING ON OUR ONGOING MOMENTUM 16 FINANCIALS 18 LOOKING AHEAD 19 BOARD OF DIRECTORS 20 THANK YOU TO OUR DONORS 2 | 2015 YEAR IN REVIEW The Perot Museum of Nature and Science has enjoyed The year 2015 was pivotal for your Museum: one of great momentum in its first three years to become discovery and decision making, introspection and the most visited cultural attraction in the Dallas-Fort inspiration, growth and gratitude. These themes — Worth region, with a guest satisfaction rating that is woven through the pages of this annual report — came second highest in the nation. The Museum earned to life through innovative programs, key partnerships the highest field trip and outreach penetration and visionary plans initiated during the fiscal year, and fostered the largest professional development and through you. Your extraordinary support and program for teachers of any North Texas science guidance has empowered us to continue inspiring the provider. News coverage of Museum programs in visionaries of tomorrow. Together, we will embolden 2015 exceeded 2,500 online mentions with nearly young minds to become the explorers, innovators and 200 unique stories in print publications and on TV problem-solvers for the next generation. and radio. Approximately 1.1 million guests from around the world walked through our glistening With your enthusiastic support, the future of the front doors last year to explore and to be inspired. -

Global Science, National Horizons: South Africa in Deep Time and Space*

The Historical Journal, , (), pp. – © The Author(s), . Published by Cambridge University Press. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/./), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi:./SX GLOBAL SCIENCE, NATIONAL HORIZONS: SOUTH AFRICA IN DEEP TIME AND SPACE* SAUL DUBOW Cambridge University ABSTRACT. In his inaugural lecture, Saul Dubow, Smuts Professor of Commonwealth History at Cambridge University, discusses the modern history of science in South Africa in terms of ‘deep time’ and space, drawing links between developments in astronomy, palaeontology, and Antarctic research. He argues that Jan Smuts’s synthetic discussion of South African science in , followed by J. H. Hofmeyr’s discussion of the ‘South Africanization’ of science in , has parallels in post- apartheid conceptions of scientific-led nation-building, for example in Thabo Mbeki’s elaboration of the ‘African Renaissance’. Yet, whereas the vision of science elaborated by Smuts was geared exclu- sively to white unity, Mbeki’s Africanist vision of South African science was ostensibly more inclusive. The lecture concludes by considering South Africa as one of several middle order countries which have used national science and scientific patriotism to address experiences of colonialism and relations of inequality and to assert their influence in regional contexts. I In an easily overlooked passage in his best-selling autobiography, Long walk to freedom, Nelson Mandela recalls how, as a secondary school student, he wit- nessed a performance by the Xhosa praise poet Krune Mqhayi in which the stars were divided amongst the nations of the world. -

OSHER/CARTA MASTER CLASS I – Fall 2020 Special Topics in Human

OSHER/CARTA MASTER CLASS I – Fall 2020 Special Topics in Human Origins Course Schedule & Significant Dates: • Wed, 30 September, 10:00 AM - 12:00 PM (PDT) • Wed, 07 October, 10:00 AM - 12:00 PM (PDT) • Wed, 04 November, 10:00 AM - 12:00 PM (PST) • Wed, 25 November, 10:00 AM - 12:00 PM (PST) • Wed, 02 December, 10:00 AM - 12:00 PM (PST) **The format is a live online one-hour lecture followed by live online question and answer period.** CARTA: The Center for Academic Research and Training in Anthropogeny Established at UC San Diego in 2008, CARTA is an international cooperative research forum exploring questions of human origins through transdisciplinary interactions and collaborations. As the word “anthropogeny” implies, CARTA’s primary goal is to apply transdisciplinary approaches to explaining two age-old questions regarding humans: Where did we come from? How did we get here? CARTA embraces many activities. It hosts thrice-yearly (Winter, Spring, and Fall) free public symposia on human origins and related topics; it offers a specialization in Anthropogeny to graduate students at UC San Diego; it curates a Museum of Primatology (MOP); and is actively compiling a Matrix of Comparative Anthropogeny (MOCA) that highlights uniquely human differences from closely related primates. In this series of talks, five prominent UCSD scholars, all CARTA members, will address different topics related to human- origins research. To learn more about CARTA, watch additional talks, and to support our mission, visit www.carta.anthropogeny.org and/or contact Community Engagement & Advancement Director, Lindsay Hunter ([email protected]). -

Lisa Holmgren

LISA HOLMGREN visual art Tiramisu bathtub, blonde, tiramisu 160 x 70 x 70 cm, 2019 A blonde man is placed in a bathtub filled with tiramisu. He calls out “Tiramisu!”, which can be translated to “Pick me up”. By stating the obvious he is simultaneously begging for someone to get him out of there. I am aiming to convey a state of ambivalence towards notions of excess, consumer culture and isolation. Människan är född fri och överallt är hon i dojor marble, wingnut, threaded rod, shoelaces 22 x 30 x 12 cm, 2018 During the hot summer of 2018 I spent three weeks at a stone carving workshop. I wanted to create and image of an object of desire which pose a physical threat to our ability to move. The rising star cave by Niklas Hoffmann Wahlbeck The “Rising Star Cave” is located in the Malmani Dolomites in South Africa. At the very end of the rising star cave, 30 meters underground, lies the “Dinaledi” chamber. It can only be reached through a narrow and steep crack that is 12 meters long with an average width of just 20 cm. In the Sotho-Tswana languages, “Dinaledi” means “Chamber of Stars”. In late 2013 a small expedition reached the Dinaledi chamber and found the bones of one owl and of 15 humanlike individuals. Tests have shown that the bones are around 300.000 years old. It seems like they were once deliberately placed in this far off cavern, indicating some kind of burial rite. They belong to a now extinct species of homini called “Homo Naledi”. -

Origins: Fossils from the Cradle of Humankind – Opening Oct

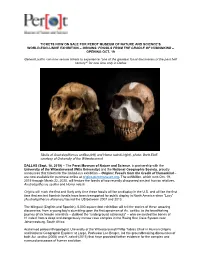

TICKETS NOW ON SALE FOR PEROT MUSEUM OF NATURE AND SCIENCE’S WORLD-EXCLUSIVE EXHIBITION – ORIGINS: FOSSILS FROM THE CRADLE OF HUMANKIND – OPENING OCT. 19 General public can now secure tickets to experience “one of the greatest fossil discoveries of the past half century*” for one time only in Dallas Skulls of Australopithecus sediba (left) and Homo naledi (right), photo: Brett Eloff, courtesy of University of the Witwatersrand DALLAS (Sept. 18, 2019) – The Perot Museum of Nature and Science, in partnership with the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits University) and the National Geographic Society, proudly announces that tickets for the limited-run exhibition – Origins: Fossils from the Cradle of Humankind – are now available for purchase online at origins.perotmuseum.org. The exhibition, which runs Oct. 19, 2019 through March 22, 2020, will feature the fossils of two recently discovered ancient human relatives, Australopithecus sediba and Homo naledi. Origins will mark the first and likely only time these fossils will be on display in the U.S. and will be the first time that ancient hominin fossils have been transported for public display in North America since “Lucy” (Australopithecus afarensis) toured the US between 2007 and 2013. The bilingual (English and Spanish), 5,000-square-foot exhibition will tell the stories of these amazing discoveries, from a young boy’s stumbling upon the first specimen of Au. sediba, to the breathtaking journey of six female scientists – dubbed the “underground astronauts” – who excavated the bones of H. naledi from a deep and dangerously narrow cave complex in the Rising Star Cave System near Johannesburg, South Africa. -

Bpeixotto CV Jan2021

BECCA PEIXOTTO, Ph.D. [email protected] EDUCATION American University, Washington, DC Ph.D. in Anthropology, Archaeology Specialization, 2017 Dissertation: “Against the Map: Resistance LanDscapes of the Great Dismal Swamp” Dr. Daniel O. Sayers, supervisor M.A., Public Anthropology, Archaeology Specialization, 2013 Thesis: “Glass in the LanDscape of the Great Dismal Swamp” Dr. Daniel O. Sayers, supervisor Universiteit van Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands M.A. (with Honours), Discourse and Argumentation Studies, 1999 Thesis: “Refugees in Press: The Otherness of Kosovan Refugees in Five British Newspapers” Prof. Teun van Dijk, thesis supervisor University of Alabama-Huntsville, Huntsville, AL B.A., Slavic Area Studies and Mathematics (cum laude), 1997 CURRENT POSITIONS Henry M. Jackson Foundation/Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, JBPHH, Hawai’i Project Archaeologist (2020-present) • Collaborate with external anD internal partners to plan anD execute archaeological activities with the goal of recovering US servicemembers lost in past conflicts arounD the worlD. American University, Washington, D.C. Adjunct Professorial Lecturer (2017-present) • Teach face-to-face, hybriD, anD online unDergraDuate courses (Human Origins; Early America: The BurieD Past; UnDergraDuate Research MethoDs). TEACHING AND RESEARCH EXPERIENCE Perot Museum of Nature and Science, Dallas, Texas Director and Research Scientist, Center for the Exploration of the Human Journey (2018-2020); Curator, Origins: Fossils from the Cradle of Humankind (2018-2021) • Develop, coorDinate, implement Museum programs relateD to paleoanthropology, archaeology, and allieD fielDs through a Center of Excellence DeDicateD to communicating the stories of our shareD human journey. • Cultivate collaborative relationships arounD outreach anD research with Prof Lee Berger, University of the WitwatersranD anD other researchers anD institutions. -

This Face Changes the Human Story. but How?

This Face Changes the Human Story. But How? NALEDI FOSSILS | News This Face Changes the Human Story. But How? Scientists have discovered a new species of human ancestor deep in a South African cave, adding a baffling new branch to the family tree. By Jamie Shreeve, National Geographic Photographs by Robert Clark PUBLISHED SEPTEMBER 10, 2015 + http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2015/09/150910-human-evolution-change/[9/18/2015 7:27:50 AM] This Face Changes the Human Story. But How? While primitive in some respects, the face, skull, and teeth show enough modern features to justify H. naledi's placement in the genus Homo. Artist Gurche spent some 700 hours reconstructing the head from bone scans, using bear fur for hair. PHOTOGRAPH BY MARK THIESSEN, NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC A trove of bones hidden deep within a South African cave represents a new species of human ancestor, scientists announced Thursday in the journal eLife. Homo naledi, as they call it, appears very primitive in some respects—it had a tiny brain, for instance, and apelike shoulders for climbing. But in other ways it looks remarkably like modern humans. When did it live? Where does it ft in the human family tree? And how did its bones get into the deepest hidden chamber of the cave—could such a primitive creature have been disposing of its dead intentionally? This is the story of one of the greatest fossil discoveries of the past half century, and of what it might mean for our understanding of human evolution. Chance Favors the Slender Caver Two years ago, a pair of recreational cavers entered a cave called Rising Star, some 30 miles northwest of Johannesburg. -

New Species of Human Relative Discovered in South African Cave Fossils Representing at Least 15 Individuals May Alter Views of Human Behaviour

New Species of Human Relative Discovered in South African Cave Fossils representing at least 15 individuals may alter views of human behaviour JOHANNESBURG—The discovery of a new species of human relative was announced today (Sept. 10) by the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits University), the National Geographic Society and the South African Department of Science and Technology/ National Research Foundation (DST/NRF). Besides shedding light on the origins and diversity of our genus, the new species, Homo naledi, appears to have intentionally deposited bodies of its dead in a remote cave chamber, a behaviour previously thought limited to humans. The finds are described in two papers published in the scientific journal eLife and reported in the cover story of the October issue of National Geographic magazine (http://natgeo.org/naledi) and a NOVA/National Geographic Special (#NalediFossils). An international team of scientists took part in the research. Consisting of more than 1,550 numbered fossil elements, the discovery is the single largest fossil hominin find yet made on the continent of Africa. The initial discovery was made in 2013 in a cave known as Rising Star in the Cradle of Humankind World Heritage Site, some 50 kilometers (30 miles) northwest of Johannesburg, South Africa, by Wits University scientists and volunteer cavers. The fossils, which have yet to be dated, lay in a chamber about 90 meters (some 100 yards) from the cave entrance, accessible only through a chute so narrow that a special team of very slender individuals was needed to retrieve them. So far, the team has recovered parts of at least 15 individuals of the same species, a small fraction of the fossils believed to remain in the chamber. -

L Weapons Seized 'Enough to Obliterate Manama'

VOL XXXVIII No. 175 (GGDN 024) FRIDAY, 11th SEPTEMBER 2015 200 Fils/2 Riyals ABC Ad new QRcode 6cm x 4col 02.pdf 1 7/6/15 11:39 AM HugeHuge oodsoods n Demand surge washwash awayaway sparks power cut MANAMA: Several areas in Bahrain experienced a power cut last night that lasted for Japan homes around two hours. Complaints Japan homes poured in from residents of a number of blocks in Eker, Sitra and Nuwaidrat. Sources 15 told the GDN that the power cut followed “excessive use of electricity”. n Police targeted MANAMA: The Khamis police station was the target of a firebomb attack, the Interior Ministry announced on its Twitter account last night. An investigation has been launched, it said. No further details were available. n Clamp on Hamas n The Foreign Minister WASHINGTON: The US Treasury Department last night sanctioned four Hamas SHOCKING officials and financiers and a Saudi Arabia-based company controlled by one of them for providing financial support to the Palestinian group. Among those named were Salih Al Aruri, a Hamas political bureau member who it said was responsible for Hamas money transfers, and Mahir Salah, a Hamas financier based in Saudi Arabia with dual British and Jordanian citizenship who Treasury said leads the Hamas finance committee in Saudi REVELATION! Arabia. Also named were Abu Ubaydah Khayri Hafiz Al Agha, a Saudi citizen, and Mohammed l Weapons seized ‘enough to obliterate Manama’ Reda Mohammed Anwar Awad, an Egyptian national. Also sanctioned was Asyaf MANAMA: Explosives seized join the regional group was in the inter- Should Iran continue with its current International Holding Group for Full report – Page 3 est of Gulf countries. -

Jeremy M. Desilva

Curriculum Vitae Jeremy M. DeSilva Dartmouth College Phone: (603) 646-8192 Department of Anthropology [email protected] 409 Silsby Hall [email protected] Hanover, NH 03755 PROFESSIONAL POSITIONS Associate Professor, Anthropology Department. Dartmouth College. 2015-present Assistant Professor, Anthropology Department. Boston University. 2009-2015. Assistant Professor, Biology Department. Worcester State College. 2008-2009. Adjunct Instructor of Biology at Northwest State Community College, Ohio. 2007-2008. Exhibit Content Developer for Human Evolution Exhibit. Boston Museum of Science. 2004 Life Science Interpretation Coordinator. Boston Museum of Science. 2000-2003 Education Fellow. Boston Museum of Science. 1999-2000 High School Biology Teacher. Somerset High School, MA. 1998-1999 EDUCATION University of Michigan Ph.D. Biological Anthropology, 2008. Thesis: VERTICAL CLIMBING ADAPTATIONS IN THE ANTHROPOID ANKLE AND MIDFOOT: IMPLICATIONS FOR LOCOMOTION IN MIOCENE CATARRHINES AND PLIO-PLEISTOCENE HOMININS. http://www.paleoanthro.org/dissertations/list/ Dissertation committee: Laura MacLatchy (Chair), D. Fisher, J. Mitani, W. Sanders, M. Wolpoff Cornell University B.A. Biology (Physiology), 1998 AFFILIATIONS & OTHER RESPONSIBILITIES • Faculty member of Ecology, Evolution, Ecosystems, and Society (EEES) graduate program at Dartmouth College and Adjunct faculty member, Department of Biological Sciences, Dartmouth College. 2015-present. • Honorary Research Fellow. Evolutionary Sciences Institute. University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa. 2014-present. • Member of the Montshire Museum of Science Corporation and Program Committee. 2016-present. • Board of Directors. The Wildebeest Tail. 2018-present. • Board of Reviewers. The Anatomical Record. 2018-present. • Public Voices Fellow. Op-Ed Project. 2018-present. • Associate Editor. Journal of Human Evolution. 2013-2015. • Affiliated research scientist. Orthopaedics Biomechanics Laboratory. Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA. -

Rising Star Expedition

INTERVIEW RISING STAR EXPEDITION A member of the 2014 award- winning Rising Star Expedition, ‘Underground Astronaut’ K Lindsay Hunter was one of six female scientists who excavated fossils of the new species, Homo naledi, from the Dinaledi Chamber of the Rising Star Cave in South Africa. Alongside a detailed description of her experience in the cave, she explains the impact of the K Lindsay Hunter during the Rising Star Expedition © Elen Feuerriegel. discovery to date Congratulations! The discovery of Homo naledi is altering our Mandible (occlusal understanding of human ancestry. What can you say, more specifically, view) © John Hawks. about the significance of these findings? Homo naledi (along with Homo floresiensis and the existence of the RISING STAR Denisovans) helps illustrate the diversity of evolutionary experiments our lineage is and was subject to, exposing the hubris of human exceptionalism. Our sole existence at this point in history may be nothing more than a quirk of fate, rather than the steady march of progress EXPEDITION even scientists have difficulty thinking past. Rather than abandoning us to nihilism and removing meaning from our existence, it reaffirms our connectedness with the rest of life on this planet. This gives us the opportunity to reassess what we feel sets us apart and be truly exceptional; to actively choose greatness rather than to feel entitled through separate creation or as the winners of some bloody competition. Evolution has meandered and drifted its path one way, but our lives are what we make of them. What initial conclusions can be drawn from the contrast between the ape- and human-like body parts identified within each skeleton? The mosaic features (both ‘ancestral’ and derived features – known technically as plesiomorphies or apomorphies) help us to relatively date the lineage to somewhere in the 2-2.5 million year realm.