GERMS of Goodi the Growth of Quakerism in Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The River Torrens—Friend and Foe Part 2

The River Torrens—friend and foe Part 2: The river as an obstacle to be crossed RICHARD VENUS Richard Venus BTech, BA, GradCertArchaeol, MIE Aust is a retired electrical engineer who now pursues his interest in forensic heritology, researching and writing about South Australia’s engineering heritage. He is Chairman of Engineering Heritage South Australia and Vice President of the History Council of South Australia. His email is [email protected] Beginnings In Part 1 we looked the River Torrens as a friend—a source of water vital to the establishment of the new settlement. However, in common with so many other European settlements, the developing community very quickly polluted its own water supply and another source had to be found. This was still the River Torrens but the water was collected in the Torrens Gorge, about 13 kilometres north-east of the City, and piped down Payneham Road to the Valve House in the East Parklands. Water from this source was first made available in December 1860 as reported in the South Australian Advertiser on 26 December. The significant challenge presented by the Torrens was getting across it. In summer, when the river was little more than a series of pools, you could just walk across. However, there must have been a significant body of water somewhere – probably in the vicinity of today’s weir – because in July 1838 tenders were called ‘For the rent for six months of the small punt on the Torrens for foot passengers, for each of whom a toll of one penny will be authorised to be charged from day-light to dark, and two pence after dark’ (Register 28 July). -

Place Names of South Australia: W

W Some of our names have apparently been given to the places by drunken bushmen andfrom our scrupulosity in interfering with the liberty of the subject, an inflection of no light character has to be borne by those who come after them. SheaoakLog ispassable... as it has an interesting historical association connectedwith it. But what shall we say for Skillogolee Creek? Are we ever to be reminded of thin gruel days at Dotheboy’s Hall or the parish poor house. (Register, 7 October 1861, page 3c) Wabricoola - A property North -East of Black Rock; see pastoral lease no. 1634. Waddikee - A town, 32 km South-West of Kimba, proclaimed on 14 July 1927, took its name from the adjacent well and rock called wadiki where J.C. Darke was killed by Aborigines on 24 October 1844. Waddikee School opened in 1942 and closed in 1945. Aboriginal for ‘wattle’. ( See Darke Peak, Pugatharri & Koongawa, Hundred of) Waddington Bluff - On section 98, Hundred of Waroonee, probably recalls James Waddington, described as an ‘overseer of Waukaringa’. Wadella - A school near Tumby Bay in the Hundred of Hutchison opened on 1 July 1914 by Jessie Ormiston; it closed in 1926. Wadjalawi - A tea tree swamp in the Hundred of Coonarie, west of Point Davenport; an Aboriginal word meaning ‘bull ant water’. Wadmore - G.W. Goyder named Wadmore Hill, near Lyndhurst, after George Wadmore, a survey employee who was born in Plymouth, England, arrived in the John Woodall in 1849 and died at Woodside on 7 August 1918. W.R. Wadmore, Mayor of Campbelltown, was honoured in 1972 when his name was given to Wadmore Park in Maryvale Road, Campbelltown. -

Understanding the Reasons Behind the Failure of Wakefield's Systematic Colonization in South

When Colonization Goes South: Understanding the Reasons Behind the Failure of Wakefield’s Systematic Colonization in South Australia Edwyna Harris Monash University Sumner La Croix* University of Hawai‘i 3 December 2018 Abstract Britain after the Napoleonic wars saw the rise of colonial reformers, such as Edward Wakefield, who had extensive influence on British colonial policy. A version of Wakefield’s “System of Colonization” became the basis for an 1834 Act of Parliament establishing the South Australia colony. We use extended versions of Robert Lucas’s 1990 model of a colonial economy to illustrate how Wakefield’s institutions were designed to work. Actual practice followed some of Wakefield’s principles to the letter, with revenues from SA land sales used to subsidize passage for more than 15,000 emigrants over the 1836-1840 period. Other principles, such as surveying land in advance of settlement and maintaining a sufficient price of land, were ignored. Initial problems stemming from delays in surveying and a dysfunctional division of executive authority slowed the economy’s development over its first three years and led to a financial crisis. These difficulties aside, we show that actual SA land institutions were more aligned with geographic and political conditions in SA than the ideal Wakefield institutions and that the SA colony thrived after it took measures to speed surveying and reform its system of divided executive authority. Please do not quote or cite or distribute without permission © For Presentation at the ASSA Meetings, Atlanta, Georgia January 4, 8-10 am, Atlanta Marriott Marquis, L505 Key words: Adelaide; colonization; priority land order; South Australia; auction; Wakefield; special surveys; land concentration; emigration JEL codes: N47, N57, N97, R30, D44 *Edwyna Harris, Dept. -

The National Library of Australia Magazine

THE NATIONAL LIBRARY DECEMBEROF AUSTRALIA 2014 MAGAZINE KEEPSAKES PETROV POEMS GOULD’S LOST ANIMALS WILD MAN OF BOTANY BAY DEMISE OF THE EMDEN AND MUCH MORE … keepsakes australians and the great war 26 November 2014–19 July 2015 National Library of Australia Free Exhibition Gallery Open Daily 9 am–5 pm nla.gov.au #NLAkeepsakes James C. Cruden, Wedding portrait of Kate McLeod and George Searle of Coogee, Sydney, 1915, nla.pic-vn6540284 VOLUME 6 NUMBER 4 DECEMBER 2014 TheNationalLibraryofAustraliamagazine The aim of the quarterly The National Library of Australia Magazine is to inform the Australian community about the National Library of Australia’s collections and services, and its role as the information resource for the nation. Copies are distributed through the Australian library network to state, public and community libraries and most libraries within tertiary-education institutions. Copies are also made available to the Library’s international associates, and state and federal government departments and parliamentarians. Additional CONTENTS copies of the magazine may be obtained by libraries, public institutions and educational authorities. Individuals may receive copies by mail by becoming a member of the Friends of the National Library of Australia. National Library of Australia Parkes Place Keepsakes: Australians Canberra ACT 2600 02 6262 1111 and the Great War nla.gov.au Guy Hansen introduces some of the mementos NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA COUNCIL of war—personal, political and poignant—featured Chair: Mr Ryan Stokes Deputy -

Summary of State Heritage Place

South Australian HERITAGE COUNCIL SUMMARY OF STATE HERITAGE PLACE REGISTER ENTRY Entry in the South Australian Heritage Register in accordance with the Heritage Places Act 1993 NAME: Houghton Union Chapel PLACE NO.: 26493 ADDRESS: 21 Blackhill Road, Houghton SA 5131 CT 5462/764 AL2 FP3148 Hundred Yatala STATEMENT OF HERITAGE SIGNIFICANCE The Houghton Union Chapel is one of the earliest church, school and community buildings in the State, and has significant associations with the early religious development of South Australia. The Houghton Chapel was built cooperatively by members of the Wesleyan Methodist, Congregational and Episcopalian Churches in 1845, and was shared by them as a place of worship until 1874. South Australia was founded on principles of non-discrimination against dissenting denominations. Demonstrating the religious freedom the first settlers to South Australia enjoyed, the Houghton Union Chapel has significant associations with the distinctive early religious development of the colony, and in particular with the religious cooperation that prompted the construction of several multi-denominational or ‘Union’ Chapels. The building was also used as a local primary school from 1847 until 1877 and is one of the earliest examples of a building used for schooling prior to the standardisation of education in South Australia in 1875. The Chapel has been little altered for over 160 years, and thus provides a rare insight into early construction techniques and materials, as well as into the design of early church buildings. Summary of State Heritage Place: 26493 Confirmed by the South Australian Heritage Council 11 April 2019 1 of 17 RELEVANT CRITERIA (under section 16 of the Heritage Places Act 1993) (a) it demonstrates important aspects of the evolution or pattern of the State's history The Houghton Union Chapel demonstrates significant aspects of the evolution of the State’s history, in particular the early religious development of the state. -

Heritage South Australia Newsletter

Department for Environment and Heritage Heritage South Australia Newsletter Edition 30 March 2007 In this issue: John Barton Hack & the Manning Cottages Black Hill Lodge The Lodge, Stirling George Paech’s farmhouse Steam Exchange Brewery Goolwa State Heritage Area 2006 Schools Heritage Competition Woolshed Flat Church Burra Regional Art Gallery Frederick Dancker Heritage Southwww.environment.sa.gov.au Australia Newsletter March 2007 DEH has contributed financial support Contents to an innovative heritage project in partnership with the Adelaide 3 Heritage Places City Council to conserve the former John Barton Hack & Beresford Arms Inn in Gilles Street. This the Manning Cottages important heritage building is one of the few non-government or religious 150th Anniversary-Black Hill Lodge buildings within the city remaining The Lodge, Stirling relatively intact from the earliest years George Paech’s farmhouse of settlement. 7 Adaptive Re-use On a broader scale, the practical side of heritage conservation received a Steam Exchange Brewery boost with the allocation of more than 8 State Heritage Areas $244,000 to 54 projects to repair and restore State Heritage Places across Goolwa Minister’s South Australia. Funds were directed 9 2006 Schools Heritage towards conservation and stabilisation Competition Update works, particularly where the work will enhance the financial viability of 0 Heritage Volunteers DEH is mourning the loss of a valued a place. and well-respected friend and Woolshed Flat Church colleague with the unexpected This issue also puts the spotlight on Burra Regional Art Gallery passing of Maritime Archaeologist Terry the tremendous volunteer effort that Arnott. Terry was a valued member of maintains many of our heritage places 2 Architects & Builders of SA - 3 the Heritage Branch who was held in in the best possible way – by using Frederick Dancker high regard by his colleagues across them. -

Notes and Queries STATE PAPERS There Was No Single Religious the 2Nd Volume of the Calendar Denomination Behind Sabbat of State Papers

Notes and Queries STATE PAPERS there was no single religious The 2nd volume of the Calendar denomination behind Sabbat of State Papers . Domestic arianism in the area, but that series, James II (H.M. Stationery Quakers were in the lead in south Office, 1964) covers the period Durham. from January 1686 to May 1687. The volume records various war THE APOTHECARIES' COMPANY rants, petitions and accounts A history of the Worshipful Society concerning the imprisonment of of Apothecaries of London, vol. i, Friends and orders for their 1617-1815. Abstracted and ar release, the King "being pleased ranged from the manuscript to extend his favour to those of notes of Cecil Wall by H. Charles that persuasion." Among the Cameron. Revised, annotated, cases recorded is a petition from and edited by E. Ash worth Mary, Lady Rodes, of Barl- Underwood (Oxford University borough Hall for the release of Press, 1963, 555.) contains some her Quaker steward, and the brief mention of Dr. Fothergill, of petition from John Osgood, Wil William Cookworthy of Ply liam Ingram, George Whitehead mouth who broke the company's and Gilbert Latye on behalf of monopoly and supplied drugs to over 100 Bristol Quaker prisoners the naval hospital ship Rupert, (April 1686). 1755, and William Curtis (1746- 1799) founder of the Botanical REGISTERS magazine who for five years from '' Nonconformist registers,'' by 1772 served at the Physic Garden Edwin Welch, an article in the at Chelsea as Demonstrator of Journal of the Society of Archivists, Plants. vol. 2, no. 9 (April 1964), pp. 411- 417, includes an historical BIRMINGHAM FRIENDS account of the various registers The Victoria History continues compiled by bodies not in its measured way. -

City of Port Adelaide Enfield Heritage Review

CITY OF PORT ADELAIDE ENFIELD HERITAGE REVIEW MARCH 2014 McDougall & Vines Conservation and Heritage Consultants 27 Sydenham Road, Norwood, South Australia 5067 Ph (08) 8362 6399 Fax (08) 8363 0121 Email: [email protected] PORT ADELAIDE ENFIELD HERITAGE REVIEW CONTENTS Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Objectives of Review 1.2 Stage 1 & 2 Outcomes 2.0 NARRATIVE THEMATIC HISTORY - THEMES & SUB-THEMES 3 2.1 Introduction 2.2 Chronological History of Land Division and Settlement Patterns 2.2.1 Introduction 2.2.2 Land Use to 1850 - the Old and New Ports 2.2.3 1851-1870 - Farms and Villages 2.2.4 1870-1885 - Consolidation of Settlement 2.2.5 1885-1914 - Continuing Land Division 2.2.6 1915-1927 - War and Town Planning 2.2.7 1928-1945 - Depression and Industrialisation 2.2.8 1946-1979 - Post War Development 2.3 Historic Themes 18 Theme 1: Creating Port Adelaide Enfield's Physical Environment and Context T1.1 Natural Environment T1.2 Settlement Patterns Theme 2: Governing Port Adelaide Enfield T2.1 Levels of Government T2.2 Port Governance T2.3 Law and Order T2.4 Defence T2.5 Fire Protection T2.6 Utilities Theme 3: Establishing Port Adelaide Enfield's State-Based Institutions Theme 4: Living in Port Adelaide Enfield T4.1 Housing the Community T4.2 Development of Domestic Architecture in Port Adelaide Enfield Theme 5: Building Port Adelaide Enfield's Commercial Base 33 T5.1 Port Activities T5.2 Retail Facilities T5.3 Financial Services T5.4 Hotels T5.5 Other Commercial Enterprises Theme 6: Developing Port Adelaide Enfield's Agricultural -

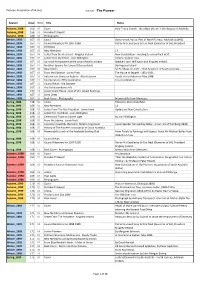

PASA Journals Index 2017 07 Brian.Xlsx

Pioneers Association of SA (Inc) Journal - "The Pioneer" Season Issue Item Title Notes Autumn_1998 166 00 Cover Holy Trinity Church - the oldest church in the diocese of Adelaide. Autumn_1998 166 01 President's Report Autumn_1998 166 02 Photographs Winter_1998 167 00 Cover Government House, Part of North Terrace, Adelaide (c1845). Winter_1998 167 01 Council Members for 1997-1998 Patron His Excellency Sir Eric Neal (Governor of SA), President Winter_1998 167 02 Portfolios Winter_1998 167 03 New Members 17 Winter_1998 167 04 Letter from the President - Kingsley Ireland New Constitution - meeting to review final draft. Winter_1998 167 05 Letter from the Editor - Joan Willington Communication lines. Winter_1998 167 06 Convivial Atmosphere at the Union Hotel Luncheon Speakers Joan Willington and Kingsley Ireland. Winter_1998 167 07 No Silver Spoons for Cavenett Descendants By Kingsley Ireland. Winter_1998 167 08 New Patron Sir Eric Neal, AC, CVO - 32nd Governor of South Australia. Winter_1998 167 09 From the Librarian - Lorna Pratt The House of Seppelt - 1851-1951. Winter_1998 167 10 Autumn sun shines on Auburn - Alan Paterson Coach trip to Auburn in May 1998. Winter_1998 167 11 Incorporation of The Association For consideration. Winter_1998 167 12 Council News - Dia Dowsett Winter_1998 167 13 The Correspondence File Winter_1998 167 14 Government House - One of SA's Oldest Buildings Winter_1998 167 15 Diary Dates Winter_1998 167 16 Back Cover - Photographs Memorabilia from Members. Spring_1998 168 00 Cover Edward Gibbon Wakefield. Spring_1998 168 01 New Members 14 Spring_1998 168 02 Letter From The Vice President - Jamie Irwin Update on New Constitution. Spring_1998 168 03 Letter fron the Editor - Joan Willington Spring_1998 168 04 Ceremonial Toast to Colonel Light By Joan Willington. -

The Journal of John Barton Hack

The Journal of John Barton Hack Collated by Chris Durrant This transcription is based on the typewritten transcriptions in the State Library of South Australia and State Library of New South Wales. The latter transcriptions are similar, but not identical; the transcribers are not identified, but may well be Lewis Darton and John Barton Hack (junior). These have been checked against the maunscript in the State Library of South Australia (PRG 456/6). Minor spelling errors have been silently corrected. The few cases of uncertainty in the transcription are indicated by [?]. The punctuation in the manuscript and both typescripts is erratic and inconsistent. This version tries only to make the best sense of the text. 1836 6 mo 18 Agreed with B. Adames to let him have Greyling Wells for the ensuing 5 years for £335, and procured Wm. Sowton’s consent in writing to underlet to B.A. Sent away C. Toomer, who was discovered to have taken many articles belonging to us. 6 mo 20 Set off at 5 oclock this morning for Portsmo: Went on board the Emerald Isle, steam packet, which First was detained till 1 oclock in the afternoon alongside the Buffalo—she had brought upwards of 20 tons day of goods belonging to South Australian emigrants from London. Soon after passing the Needles the swell became rather annoying to us, and the wind rose & became rather cold. Dinner at four oclock. Soon after Bbe & I became very sick—Annie had been in her berth for some time before. We soon after six gave up being on deck, and went down to lie down and make the best we could of it. -

Adelaide Hills Wine Region.Pdf

From: Emma Barnes To: DPTI:Planning Reform Submissions Subject: Draft Planning and Design Code Submission | Adelaide Hills Wine Region Date: Friday, 28 February 2020 12:43:17 PM Attachments: 200228 P0144 AHWR Draft Planning and Design Code Submission Final.pdf Attention: Mr Michael Lennon Chair State Planning Commission Dear Mr Lennon Please find attached a submission in relation on the Draft Planning and Design Code for South Australia prepared on behalf of the Adelaide Hills Wine Region. The submission has also been uploaded via the online form at https://www.saplanningportal.sa.gov.au/have_your_say/Draft_Planning_and_Design_Code_for_South_Australia#feedback On behalf of the Adelaide Hills Wine Region, we thank you for providing an opportunity to make a submission on the Draft Planning and Design Code and look forward to working with the Commission and the Department on this significant reform package to ensure the Adelaide Hills Wine Region achieves its full potential as a world class food production and tourism destination. Should you wish to discuss any aspects of this submission further, please do not hesitate to contact me. Regards Emma Emma Barnes | Director | Planning Studio | Urban & Regional Planning | | PO Box 32 Bridgewater SA 5155 The information contained in this email is intended for the named recipient only and may be confidential, legally privileged or commercially sensitive. If you are not the intended recipient you must not reproduce or distribute any part of this email, disclose its contents to any other party, or take any action in reliance on it. If you have received this email in error, please contact the sender immediately. -

Place Name SUMMARY (PNS) 4.04.01/01 NGALTINGGA

The Southern Kaurna Place Names Project The author gratefully acknowledges the Yitpi Foundation for the grant which funded the writing of this essay. This and other essays may be downloaded free of charge from https://www.adelaide.edu.au/kwp/placenames/research-publ/ Place Name SUMMARY (PNS) 4.04.01/01 NGALTINGGA (last edited: 7.11.2017) See also PNS 4.04.01/06 Kauwi Ngaltingga anD PNS 4.04.01/03 Wakondilla NOTE AND DISCLAIMER: This essay has not been peer-reviewed or culturally endorsed in detail. The spellings and interpretations contained in it (linguistic, historical and geographical) are my own, and do not necessarily represent the views of KWP/KWK or its members or any other group. I have studied history at tertiary level. Though not a linguist, for 30 years I have learned much about the Kaurna, Ramindjeri-Ngarrindjeri and Narungga languages while working with KWP, Rob Amery, and other local culture- reclamation groups; and from primary documents I have learned much about the Aboriginal history of the Adelaide-Fleurieu region. My explorations of 'language on the land' through the Southern Kaurna Place Names Project are part of an ongoing effort to correct the record about Aboriginal place-names in this region (which has abounded in confusions and errors), and to add reliable new material into the public domain. I hope upcoming generations will continue this work and improve it. My interpretations should be amplified, re- considered and if necessary modified by KWP or other linguists, and by others engaged in cultural mapping: Aboriginal people, archaeologists, geographers, ecologists and historians.