Jat Community's Appropriation of Social Mores Against the Imperial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

Development of Iconic Tourism Sites in India

Braj Development Plan for Braj Region of Uttar Pradesh - Inception Report (May 2019) INCEPTION REPORT May 2019 PREPARATION OF BRAJ DEVELOPMENT PLAN FOR BRAJ REGION UTTAR PRADESH Prepared for: Uttar Pradesh Braj Tirth Vikas Parishad, Uttar Pradesh Prepared By: Design Associates Inc. EcoUrbs Consultants PVT. LTD Design Associates Inc.| Ecourbs Consultants| Page | 1 Braj Development Plan for Braj Region of Uttar Pradesh - Inception Report (May 2019) DISCLAIMER This document has been prepared by Design Associates Inc. and Ecourbs Consultants for the internal consumption and use of Uttar Pradesh Braj Teerth Vikas Parishad and related government bodies and for discussion with internal and external audiences. This document has been prepared based on public domain sources, secondary & primary research, stakeholder interactions and internal database of the Consultants. It is, however, to be noted that this report has been prepared by Consultants in best faith, with assumptions and estimates considered to be appropriate and reasonable but cannot be guaranteed. There might be inadvertent omissions/errors/aberrations owing to situations and conditions out of the control of the Consultants. Further, the report has been prepared on a best-effort basis, based on inputs considered appropriate as of the mentioned date of the report. Consultants do not take any responsibility for the correctness of the data, analysis & recommendations made in the report. Neither this document nor any of its contents can be used for any purpose other than stated above, without the prior written consent from Uttar Pradesh Braj Teerth Vikas Parishadand the Consultants. Design Associates Inc.| Ecourbs Consultants| Page | 2 Braj Development Plan for Braj Region of Uttar Pradesh - Inception Report (May 2019) TABLE OF CONTENTS DISCLAIMER ......................................................................................................................................... -

Causelist Dated:- 05-08-2021

Page No. : 163 THE HIGH COURT OF JAMMU & KASHMIR AND LADAKH AT JAMMU AFTER NOTICE CAUSELIST COURT NO. : 1 05/08/2021 [Thursday] HON'BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE PUNEET GUPTA AFTER NOTICE 201 OWP 1083/2007 OASIS HOTEL RESORT PVT.LTD. PRANAV KOHLI FOR PET IA(1570/2007) Vs BUILDING OPERATION SONIA GUPTA FOR RES CONT.AUTH.AND ORS. 202 OWP 1329/2012 VIRENDER PANDOH RAHUL BHARTI FOR PET IA(1858/2012) Vs STATE H A SIDDIQUI SR AAG FOR RES TH.DY.COMMSSIONER,REASI AND ADITYA SHARMA FOR PET ORS. MEHARBAN SINGH FOR PET MR.SATINDER GUOTA FOR PET M P SHARMA FOR RES O P THAKUR FOR RES 203 CPLPA 1/2013 SUDESH KUMAR GARGOTRA PETITONER IN PERSON FOR PET CM(4321/2019) Vs RANJIT SINHA, D.G., I.T.B.P N A CHOUDHARY FOR RES AND ORS. in SWP 1035/2014 SUDESH KUMAR GARGOTRA NONU KHERA FOR PET Vs UOI TH.MIN.OF HOME AFFAIRS N A CHOUDHARY,CGSC FOR RES AND ORS. RAVI ABROL FOR PET IN PERSON FOR PET SUNIL SETHI SR ADV FOR PET 204 OWP 1231/2015 KOUSHAL GUPTA GAGAN BASOTRA FOR PET IA(1/2015) Vs STATE TH.U.D.D.AND ORS. S S NANDA SR AAG FOR RES CM(5108/2021) RAJNISH RAINA FOR RES 205 CM(6351/2020) IN KRISHAN LAL AND ORS MR.AJAY KUMAR FOR PET CPLPA 15/2016 Vs VINOD KUMAR MR.EHSAN MIRZA,DY.AG FOR KOUL,SECY.REVENUE AND ORS. RES AJAY KUMAR FOR PET 206 OWP 1454/2017 CHUNI LAL AND ORS. -

Castes and Caste Relationships

Chapter 4 Castes and Caste Relationships Introduction In order to understand the agrarian system in any Indian local community it is necessary to understand the workings of the caste system, since caste patterns much social and economic behaviour. The major responses to the uncertain environment of western Rajasthan involve utilising a wide variety of resources, either by spreading risks within the agro-pastoral economy, by moving into other physical regions (through nomadism) or by tapping in to the national economy, through civil service, military service or other employment. In this chapter I aim to show how tapping in to diverse resource levels can be facilitated by some aspects of caste organisation. To a certain extent members of different castes have different strategies consonant with their economic status and with organisational features of their caste. One aspect of this is that the higher castes, which constitute an upper class at the village level, are able to utilise alternative resources more easily than the lower castes, because the options are more restricted for those castes which own little land. This aspect will be raised in this chapter and developed later. I wish to emphasise that the use of the term 'class' in this context refers to a local level class structure defined in terms of economic criteria (essentially land ownership). All of the people in Hinganiya, and most of the people throughout the village cluster, would rank very low in a class system defined nationally or even on a district basis. While the differences loom large on a local level, they are relatively minor in the wider context. -

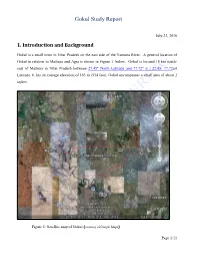

Gokul Study Report

Gokul Study Report July 23, 2016 1. Introduction and Background Gokul is a small town in Uttar Pradesh on the east side of the Yamuna River. A general location of Gokul in relation to Mathura and Agra is shown in Figure 1. below. Gokul is located 15 km south- east of Mathura in Uttar Pradesh between 27.45° North Latitude and 77.72° E / 27.45; 77.72ast Latitude. It has an average elevation of 163 m (534 feet). Gokul encompasses a small area of about 2 sq km. Figure 1: Satellite map of Gokul (courtesy of Google Maps) Page 1/11 According to Vedic Scripture, Lord Krishna was brought up under the care of Nanda and Yoshoda, the first family of the village. Since Kangsha, Krishna's uncle, used to kill every baby born to Devaki, Nanda exchanged his own new born daughter with Vasudeva in order to smuggle Krishna away without raising Kangsha's suspicion. During his stay at Gokul, Krishna spent his time in fun and frolic, though his life did come under threat a few times. He was very naughty as a child, and when Krishna was an infant, and the demoness Putana came to the village at the appeal of Kangsha. She laced her nipples with poison and tried to breastfeed Krishna. However, Krishna suckled on her until he completely drained her life away. The river Yamuna used to flow near the village as it still does, and a five-headed serpent known as Kaliya used to live in its waters. Kāliyā was a powerful cobra, who made the river waters poisonous and made the forests barren. -

The Land of Lord Krishna

Tour Code : AKSR0381 Tour Type : Spiritual Tours (domestic) 1800 233 9008 THE LAND OF LORD www.akshartours.com KRISHNA 5 Nights / 6 Days PACKAGE OVERVIEW 1Country 1Cities 6Days Accomodation Meal 3 Nights Hotel Accommodation at mathura 05 Breakfast 2 Nights Hotel Accommodation at Delhi Visa & Taxes Highlights 5 % Gst Extra Accommodation on double sharing Breakfast and dinner at hotel Transfer and sightseeing by pvt vehicle as per program Applicable hotel taxes SIGHTSEEINGS OVERVIEW Delhi :- Laxmi Narayan Temple, Hanuman Mandir, Mathura :- birth place of Lord Krishna Gokul :- Gokul Nath Ji Temple, Agra :- Taj Mahal SIGHTSEEINGS Laxmi Narayan Temple Delhi The Laxminarayan Temple, also known as the Birla Mandir is a Hindu temple up to large extent dedicated to Laxminarayan in Delhi, India. ... The temple is spread over 7.5 acres, adorned with many shrines, fountains, and a large garden with Hindu and Nationalistic sculptures, and also houses Geeta Bhawan for discourses. Hanuman Mandir Delhi Hanuman Temple in Connaught Place, New Delhi, is an ancient Hindu temple and is claimed to be one of the five temples of Mahabharata days in Delhi. ... The idol in the temple, devotionally worshipped as "Sri Hanuman Ji Maharaj" (Great Lord Hanuman), is that of Bala Hanuman namely, Birth place of Lord Krishna Mathura In Hinduism, Mathura is believed to be the birthplace of Krishna, which is located at the Krishna Janmasthan Temple Complex.[5] It is one of the Sapta Puri, the seven cities considered holy by Hindus. The Kesava Deo Temple was built in ancient times on the site of Krishna's birthplace (an underground prison). -

List of Class Wise Ulbs of Uttar Pradesh

List of Class wise ULBs of Uttar Pradesh Classification Nos. Name of Town I Class 50 Moradabad, Meerut, Ghazia bad, Aligarh, Agra, Bareilly , Lucknow , Kanpur , Jhansi, Allahabad , (100,000 & above Population) Gorakhpur & Varanasi (all Nagar Nigam) Saharanpur, Muzaffarnagar, Sambhal, Chandausi, Rampur, Amroha, Hapur, Modinagar, Loni, Bulandshahr , Hathras, Mathura, Firozabad, Etah, Badaun, Pilibhit, Shahjahanpur, Lakhimpur, Sitapur, Hardoi , Unnao, Raebareli, Farrukkhabad, Etawah, Orai, Lalitpur, Banda, Fatehpur, Faizabad, Sultanpur, Bahraich, Gonda, Basti , Deoria, Maunath Bhanjan, Ballia, Jaunpur & Mirzapur (all Nagar Palika Parishad) II Class 56 Deoband, Gangoh, Shamli, Kairana, Khatauli, Kiratpur, Chandpur, Najibabad, Bijnor, Nagina, Sherkot, (50,000 - 99,999 Population) Hasanpur, Mawana, Baraut, Muradnagar, Pilkhuwa, Dadri, Sikandrabad, Jahangirabad, Khurja, Vrindavan, Sikohabad,Tundla, Kasganj, Mainpuri, Sahaswan, Ujhani, Beheri, Faridpur, Bisalpur, Tilhar, Gola Gokarannath, Laharpur, Shahabad, Gangaghat, Kannauj, Chhibramau, Auraiya, Konch, Jalaun, Mauranipur, Rath, Mahoba, Pratapgarh, Nawabganj, Tanda, Nanpara, Balrampur, Mubarakpur, Azamgarh, Ghazipur, Mughalsarai & Bhadohi (all Nagar Palika Parishad) Obra, Renukoot & Pipri (all Nagar Panchayat) III Class 167 Nakur, Kandhla, Afzalgarh, Seohara, Dhampur, Nehtaur, Noorpur, Thakurdwara, Bilari, Bahjoi, Tanda, Bilaspur, (20,000 - 49,999 Population) Suar, Milak, Bachhraon, Dhanaura, Sardhana, Bagpat, Garmukteshwer, Anupshahar, Gulathi, Siana, Dibai, Shikarpur, Atrauli, Khair, Sikandra -

Provisional List of Not Shortlisted Candidates for the Post of Staff Nurse Under NHM, Assam (Ref: Advt No

Provisional List of Not Shortlisted Candidates for the post of Staff Nurse under NHM, Assam (Ref: Advt No. NHM/Esstt/Adv/115/08-09/Pt-II/ 4621 dated 24th Jun 2016 and vide No. NHM/Esstt/Adv/115/08-09/Pt- II/ 4582 dated 26th Aug 2016) Sl No. Regd. ID Candidate Name Father's Name Address Remarks for Not Shortlisting C/o-KAMINENI HOSPITALS, H.No.-4-1-1227, Vill/Town- Assam Nurses' Midwives' and A KING KOTI, HYDERABAD, P.O.-ABIDS, P.S.-KOTI Health Visitors' Council 1 NHM/SNRS/0658 A THULASI VENKATARAMANACHARI SULTHAN BAZAR, Dist.-RANGA REDDY, State- Registration Number Not TELANGANA, Pin-500001 Provided C/o-ABDUL AZIZ, H.No.-H NO 62 WARD NO 9, Assam Nurses' Midwives' and Vill/Town-GALI NO 1 PURAI ABADI, P.O.-SRI Health Visitors' Council 2 NHM/SNRS/0444 AABID AHMED ABDUL AZIZ GANGANAGAR, P.S.-SRI GANGANAGAR, Dist.-SRI Registration Number Not GANGANAGAR, State-RAJASTHAN, Pin-335001 Provided C/o-KHANDA FALSA MIYON KA CHOWK, H.No.-452, Assam Nurses' Midwives' and Vill/Town-JODHPUR, P.O.-SIWANCHI GATE, P.S.- Health Visitors' Council 3 NHM/SNRS/0144 ABDUL NADEEM ABDUL HABIB KHANDA FALSA, Dist.-Outside State, State-RAJASTHAN, Registration Number Not Pin-342001 Provided Assam Nurses' Midwives' and C/o-SIRMOHAR MEENA, H.No.-, Vill/Town-SOP, P.O.- Health Visitors' Council 4 NHM/SNRS/1703 ABHAYRAJ MEENA SIRMOHAR MEENA SOP, P.S.-NADOTI, Dist.-KAROULI, State-RAJASTHAN, Registration Number Not Pin-322204 Provided Assam Nurses' Midwives' and C/o-ABIDUNNISA, H.No.-90SF, Vill/Town- Health Visitors' Council 5 NHM/SNRS/0960 ABIDUNNISA ABDUL MUNAF KHAIRTABAD, -

Oral History and the Evolution of Thakuri Political Authority in a Subregion of Far Western Nepal Walter F

Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 4 Number 2 Himalayan Research Bulletin, Monsoon Article 7 1984 1984 Oral History and the Evolution of Thakuri Political Authority in A Subregion of Far Western Nepal Walter F. Winkler Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Winkler, Walter F. (1984) "Oral History and the Evolution of Thakuri Political Authority in A Subregion of Far Western Nepal," Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies: Vol. 4: No. 2, Article 7. Available at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol4/iss2/7 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ... ORAL HISTORY AND THE EVOLUTION OF THAKUR! POLITICAL AUTHORITY IN A SUBREGION OF FAR WESTERN NEPAL Walter F. Winkler Prologue John Hitchcock in an article published in 1974 discussed the evolution of caste organization in Nepal in light of Tucci's investigations of the Malia Kingdom of Western Nepal. My dissertation research, of which the following material is a part, was an outgrowth of questions John had raised on this subject. At first glance the material written in 1978 may appear removed fr om the interests of a management development specialist in a contemporary Dallas high technology company. At closer inspection, however, its central themes - the legitimization of hierarchical relationships, the "her o" as an organizational symbol, and th~ impact of local culture on organizational function and design - are issues that are relevant to industrial as well as caste organization. -

Notice for Appointment of Regular/Rural Retail Outlets Dealerships

Notice for appointment of Regular/Rural Retail Outlets Dealerships Hindustan Petroleum Corporation Limited proposes to appoint Retail Outlet dealers in the State of Uttar Pradesh, as per following details: Fixed Fee Minimum Dimension (in / Min bid Security Estimated Type of Finance to be arranged by the Mode of amount ( Deposit ( Sl. No. Name Of Location Revenue District Type of RO M.)/Area of the site (in Sq. Site* applicant (Rs in Lakhs) selection monthly Sales Category M.). * Rs in Rs in Potential # Lakhs) Lakhs) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9a 9b 10 11 12 SC/SC CC 1/SC PH/ST/ST CC Estimated Estimated fund 1/ST working required for PH/OBC/OBC CC/DC/ capital Draw of Regular/Rural MS+HSD in Kls Frontage Depth Area development of CC 1/OBC CFS requirement Lots/Bidding infrastructure at PH/OPEN/OPE for operation RO N CC 1/OPEN of RO CC 2/OPEN PH ON LHS, BETWEEN KM STONE NO. 0 TO 8 ON 1 NH-AB(AGRA BYPASS) WHILE GOING FROM AGRA REGULAR 150 SC CFS 40 45 1800 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 3 MATHURA TO GWALIOR UPTO 3 KM FROM INTERSECTION OF SHASTRIPURAM- VAYUVIHAR ROAD & AGRA 2 AGRA REGULAR 150 SC CFS 20 20 400 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 3 BHARATPUR ROAD ON VAYU VIHAR ROAD TOWARDS SHASTRIPURAM ON LHS ,BETWEEN KM STONE NO 136 TO 141, 3 ALIGARH REGULAR 150 SC CFS 40 45 1800 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 3 ON BULANDSHAHR-ETAH ROAD (NH-91) WITHIN 6 KM FROM DIBAI DORAHA TOWARDS 4 NARORA ON ALIGARH-MORADABAD ROAD BULANDSHAHR REGULAR 150 SC CFS 40 45 1800 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 3 (NH 509) WITHIN MUNICIAPL LIMITS OF BADAUN CITY 5 BUDAUN REGULAR 120 SC CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Draw of Lots 0 3 ON BAREILLY -

Vrindaban Days

Vrindaban Days Memories of an Indian Holy Town By Hayagriva Swami Table of Contents: Acknowledgements! 4 CHAPTER 1. Indraprastha! 5 CHAPTER 2. Road to Mathura! 10 CHAPTER 3. A Brief History! 16 CHAPTER 4. Road to Vrindaban! 22 CHAPTER 5. Srila Prabhupada at Radha Damodar! 27 CHAPTER 6. Darshan! 38 CHAPTER 7. On the Rooftop! 42 CHAPTER 8. Vrindaban Morn! 46 CHAPTER 9. Madana Mohana and Govindaji! 53 CHAPTER 10. Radha Damodar Pastimes! 62 CHAPTER 11. Raman Reti! 71 CHAPTER 12. The Kesi Ghat Palace! 78 CHAPTER 13. The Rasa-Lila Grounds! 84 CHAPTER 14. The Dance! 90 CHAPTER 15. The Parikrama! 95 CHAPTER 16. Touring Vrindaban’s Temples! 102 CHAPTER 17. A Pilgrimage of Braja Mandala! 111 CHAPTER 18. Radha Kund! 125 CHAPTER 19. Mathura Pilgrimage! 131 CHAPTER 20. Govardhan Puja! 140 CHAPTER 21. The Silver Swing! 146 CHAPTER 22. The Siege! 153 CHAPTER 23. Reconciliation! 157 CHAPTER 24. Last Days! 164 CHAPTER 25. Departure! 169 More Free Downloads at: www.krishnapath.org This transcendental land of Vrindaban is populated by goddesses of fortune, who manifest as milkmaids and love Krishna above everything. The trees here fulfill all desires, and the waters of immortality flow through land made of philosopher’s stone. Here, all speech is song, all walking is dancing and the flute is the Lord’s constant companion. Cows flood the land with abundant milk, and everything is self-luminous, like the sun. Since every moment in Vrindaban is spent in loving service to Krishna, there is no past, present, or future. —Brahma Samhita Acknowledgements Thanks go to Dr. -

P Age | 1 Mathura Vrindavan Yaatraa

P a g e | 1 Mathura Vrindavan Yaatraa Mathura Vrindavan Yaatra As you all knows that, Mathura Vrindavan is world famous Hindu religious tourism place and famous for Lord Krishna birthplace, temple and activates. We are placing some information regarding Mathura Vrindavan Tour Packages. During Mathura Vrindavan tour, you may cover the following places. Place to Visits : Mathura : Lord krishna Birthplace, Dwarkadhish Temple, Birla Temple, Mathura Museum, Yamuna Ghat's Vrindavan: Bankey Bihari Temple, Iskcon Temple, Radha Ballabh Temple, Prem Mandir, Nidhi Van, Kesi Ghata and Yamuna River etc. P a g e | 2 Mathura Vrindavan Yaatraa Gokul: Childhood living place of lord Krishna Near Mathura Nand Gayon: Village of lord krishna relatives Goverdhan: Goverdhan Mountain and Parikrma, Radha Kund, Kusam Sarowar Barsana: Birthplace of Radha Rani and Temples Radha Rani: Famous Temple of Radha Rani near Mathura Bhandiravan: Radhak Krishn Marriage Place, Near Mant Mathura TOURIST PLACE AT DISTRICT MATHURA MATHURA What to See SHRI KRISHNA JANMA BHUMI : The Birth Place of Lord Krishna JAMA MASJID : Built by Abo-inNabir-Khan in 1661.A.D. the mosque has 4 lofty minarets, with bright colored plaster mosaic of which a few panels currently exist. VISHRAM GHAT : The sacred spot where Lord Krishna is believed to have rested after slaying the tyrant Kansa. DWARKADHEESH TEMPLE : Built in 1814, it is the main temple in the town. During the festive days of Holi, Janmashthami and Diwali, it is decorated on a grandiose scale. GITA MANDIR : Situated on the city outskirts, the temple carving and painting are a major attraction. GOVT. MESEUM : Located at Dampier Park, it has one of the finest collection of archaeological interest.