“Too Many Mind”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baker Marquart and Quinn Emanuel Win Jury Verdict in Last Samurai Case

Baker Marquart and Quinn Emanuel Win Jury Verdict in Last Samurai Case Law360, New York (May 24, 2012, 11:30 AM ET) -- With the reputations of “The Last Samurai” director Edward Zwick and his longtime collaborator Marshall Herskovitz on the line, Gary Gans of Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan LLP fought back against allegations of screenplay theft with a multipronged strategy that used the film itself as its own defense. The case centered on two screenwriting brothers, Aaron and Matthew Benay, who in 2005 claimed Zwick and Herskovitz, along with Bedford Falls Productions, had stolen the idea for the 2003 Tom Cruise film from a screenplay the Benay brothers had allegedly submitted to Bedford Falls. Zwick and Herskovitz, longtime collaborators behind films like “Traffic” and “Blood Diamond” and television shows like “Thirtysomething” and “My So-Called Life,” denied using the Benays’ screenplay in writing and producing their film. They asserted that the evidence showed their project was the product of an intense collaboration with “Gladiator” writer John Logan. While the claims of copyright infringement and breach of implied contract were tossed in 2008, two years later, the Ninth Circuit reversed the dismissal of the breach-of-implied- contract claim while affirming the dismissal of the copyright claim. Gans came to the conclusion that the central theme of the movie — honor — was one of the pathways to his clients’ vindication. “The key to this case from my viewpoint was that the movie was largely about honor,” Gans told Law360. “We tried to channel that theme and the emotion of the movie so that they would be associated not only with the movie, but also with our clients in the courtroom as honorable people — which they are — and to show that they had no need or desire to steal someone else's ideas.” What was fundamental to that line of reasoning was to avoid falling into the trap of being labeled the Hollywood establishment types against the young and aspiring writers. -

06 7-26-11 TV Guide.Indd

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, July 26, 2011 Monday Evening August 1, 2011 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC The Bachelorette The Bachelorette Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live WEEK OF FRIDAY , JULY 29 THROUGH THURSDAY , AUG . 4 KBSH/CBS How I Met Mike Two Men Mike Hawaii Five-0 Local Late Show Letterman Late KSNK/NBC America's Got Talent Law Order: CI Harry's Law Local Tonight Show w/Leno Late FOX Hell's Kitchen MasterChef Local Cable Channels A&E Hoarders Hoarders Intervention Intervention Hoarders AMC The Godfather The Godfather ANIM I Shouldn't Be Alive I Shouldn't Be Alive Hostage in Paradise I Shouldn't Be Alive I Shouldn't Be Alive CNN In the Arena Piers Morgan Tonight Anderson Cooper 360 To Be Announced Piers Morgan Tonight DISC Jaws of the Pacific Rogue Sharks Summer of the Shark Rogue Sharks Summer of the Shark DISN Good Luck Shake It Bolt Phineas Phineas Wizards Wizards E! Sex-City Sex-City Ice-Coco Ice-Coco True Hollywood Story Chelsea E! News Chelsea Norton TV ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Baseball NFL Live ESPN2 SportsNation Soccer World, Poker World, Poker FAM Secret-Teen Switched at Birth Secret-Teen The 700 Club My Wife My Wife FX Earth Stood Earth Stood HGTV House Hunters Design Star High Low Hunters House House Design Star HIST Pawn Pawn American Pickers Pawn Pawn Top Gear Pawn Pawn LIFE Craigslist Killer The Protector The Protector Chris How I Met Listings: MTV True Life MTV Special Teen Wolf Teen Wolf Awkward. -

P38-39 Layout 1

lifestyle THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 5, 2013 MUSIC & MOVIES True Blood to end its run next year Photo shows Japanese actor Ken Watanabe gestures during an interview in Tokyo. — AP race yourselves, “True Blood” fans; dents of Bon Temps, but I look forward to the end is near. HBO Programming what promises to be a fantastic final Watanabe stars in Bpresident Michael Lombardo said chapter of this incredible show.” on Tuesday that the vampire drama will Brian Buckner, who took the reins for end its run next year following its sev- the show’s sixth season, said that he was enth season, which will launch next sum- “enormously proud” to be part of the Eastwood’s ‘Unforgiven’ remake mer. In a statement, Lombardo called series.”I feel enormously proud to have “True Blood” - which saw the departure been a part of the ‘True Blood’ family he Japanese remake of Clint Eastwood’s really good versus evil, according to self. And they were asking me: Who are of showrunner Alan Ball prior to its sixth since the very beginning,” says Brian ‘Unforgiven’ isn’t a mere cross-cultural Watanabe.The remake examines those issues you?”Watanabe stressed he was proud of the season - “nothing short of a defining Buckner. “I guarantee that there’s not a Tadaptation but more a tribute to the uni- further, reflecting psychological complexities legacy of Japanese films, a legacy he has helped show for HBO.”‘True Blood’ has been more talented or harder-working cast versal spirit of great filmmaking for its star Ken and introducing social issues not in the original, create in a career spanning more than three nothing short of a defining show for and crew out there, and I’d like to extend Watanabe.”I was convinced from the start that such as racial discrimination.”It reflects the decades, following legends like Toshiro Mifune HBO,” Lombardo said. -

The Influence of Bushido, Way of the Warrior, On

THE INFLUENCE OF BUSHIDO ON NATHAN ALGREN’S PERSONALITY DEVELOPMENT AS SEEN IN JOHN LOGAN’S MOVIE SCRIPT THE LAST SAMURAI A Thesis Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements to Obtain the Sarjana Pendidikan Degree in English Language Education By PRIMADHY WICAKSONO Student Number: 991214175 ENGLISH LANGUAGE EDUCATION STUDY PROGRAM DEPARTMENT OF LANGUAGE AND ARTS EDUCATION FACULTY OF TEACHERS TRAINING AND EDUCATION SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2007 THE INFLUENCE OF BUSHIDO ON NATHAN ALGREN’S PERSONALITY DEVELOPMENT AS SEEN IN JOHN LOGAN’S MOVIE SCRIPT THE LAST SAMURAI A Thesis Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements to Obtain the Sarjana Pendidikan Degree in English Language Education By PRIMADHY WICAKSONO Student Number: 991214175 ENGLISH LANGUAGE EDUCATION STUDY PROGRAM DEPARTMENT OF LANGUAGE AND ARTS EDUCATION FACULTY OF TEACHERS TRAINING AND EDUCATION SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2007 i This thesis is dedicated to My beloved Family: ENY HARYANI and ENDHY PRIAMBODO You are the best that God has given to me iv v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First of all, I would like to thank The Almighty Allah, SWT, for giving me the amazing love, courage and honor in my life. Through Allah’s love, I can stand in every moment in my life to face the sadness and happiness, and I can see that everything is beautiful. I also would like to thank my major sponsor, Drs. A. Herujiyanto, MA., Ph.D., who has devoted his time, knowledge and effort to improve this thesis. He has not only given me considerable and continual corrections, guidance, and support, but also great lessons for my life in the future. -

Modernizing the Greek Tragedy: Clint Eastwood’S Impact on the Western

Modernizing the Greek Tragedy: Clint Eastwood’s Impact on the Western Jacob A. Williams A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies University of Washington 2012 Committee: Claudia Gorbman E. Joseph Sharkey Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences Table of Contents Dedication ii Acknowledgements iii Introduction 1 Section I The Anti-Hero: Newborn or Reborn Hero? 4 Section II A Greek Tradition: Violence as Catharsis 11 Section III The Theseus Theory 21 Section IV A Modern Greek Tale: The Outlaw Josey Wales 31 Section V The Euripides Effect: Bringing the Audience on Stage 40 Section VI The Importance of the Western Myth 47 Section VII Conclusion: The Immortality of the Western 49 Bibliography 53 Sources Cited 62 i Dedication To my wife and children, whom I cherish every day: To Brandy, for always being the one person I can always count on, and for supporting me through this entire process. You are my love and my life. I couldn’t have done any of this without you. To Andrew, for always being so responsible, being an awesome big brother to your siblings, and always helping me whenever I need you. You are a good son, and I am proud of the man you are becoming. To Tristan, for always being my best friend, and my son. You never cease to amaze and inspire me. Your creativity exceeds my own. To Gracie, for being my happy “Pretty Princess.” Thank you for allowing me to see the world through the eyes of a nature-loving little girl. -

HH Available Entries.Pages

Greetings! If Hollywood Heroines: The Most Influential Women in Film History sounds like a project you would like be involved with, whether on a small or large-scale level, I would love to have you on-board! Please look at the list of names below and send your top 3 choices in descending order to [email protected]. If you’re interested in writing more than one entry, please send me your top 5 choices. You’ll notice there are several women who will have a “D," “P," “W,” and/or “A" following their name which signals that they rightfully belong to more than one category. Due to the organization of the book, names have been placed in categories for which they have been most formally recognized, however, all their roles should be addressed in their individual entry. Each entry is brief, 1000 words (approximately 4 double-spaced pages) unless otherwise noted with an asterisk. Contributors receive full credit for any entry they write. Deadlines will be assigned throughout November and early December 2017. Please let me know if you have any questions and I’m excited to begin working with you! Sincerely, Laura Bauer Laura L. S. Bauer l 310.600.3610 Film Studies Editor, Women's Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal Ph.D. Program l English Department l Claremont Graduate University Cross-reference Key ENTRIES STILL AVAILABLE Screenwriter - W Director - D as of 9/8/17 Producer - P Actor - A DIRECTORS Lois Weber (P, W, A) *1500 Major early Hollywood female director-screenwriter Penny Marshall (P, A) Big, A League of Their Own, Renaissance Man Martha -

Burke Keynote Speaker Commencement, Page 21

Burke Keynote Speaker Commencement, Page 21 Classified, Page 26 Classified, ❖ ABC News Reporter Jennifer Donelan, a native of Fairfax County, gave the keynote address for the June 17 Lake Braddock Secondary Commencement. Donelan could not emphasize enough that this moment is a Real Estate, Page 16 Real Estate, ❖ milestone and a stepping off point to the future. Camps & Schools, Page 11 Camps & Schools, ❖ Faith, Page 23 ❖ Sports, Page 24 insideinside Requested in home 6-20-08 Time sensitive material. Attention Postmaster: U.S. Postage Word Out PRSRT STD PERMIT #322 Easton, MD On Repairs Koger Firm PAID News, Page 3 Auctioned Off News, Page 3 Photo By Louise Krafft/The Connection By Louise Krafft/The Photo www.connectionnewspapers.com www.ConnectionNewspapers.com June 19-25, 2008 Volume XXII, Number 25 Burke Connection ❖ June 19-25, 2008 ❖ 1 2 ❖ Burke Connection ❖ June 19-25, 2008 www.ConnectionNewspapers.com Burke Connection Editor Michael O’Connell News 703-917-6440 or [email protected] 2 Cases, 2 Courts, Same Day Groner gave Koger his Jeffrey Koger appears in Miranda rights en route to court on attempted capital Inova Fairfax Hospital. “You are under arrest for murder of police officer. attempted capital murder Koger Firm Sold of a police officer,” Groner told Koger, who was admit- Sheriff’s Photo Sheriff’s By Ken Moore ted to the hospital in criti- Troubled management firm The Connection cal condition. On Tuesday, June 17, auctioned in bankruptcy court. effrey Scott Koger held a shotgun Judge Penney S. Azcarate against his shoulder and pointed the certified the case to a By Nicholas M. -

Available from TCG Books: I’Ll Eat You Last and Peter and Alice by John Logan

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Dafina McMillan May 21, 2013 [email protected] | 212-609-5955 Available from TCG Books: I’ll Eat You Last and Peter and Alice by John Logan NEW YORK, NY – Theatre Communications Group (TCG) is pleased to announce the availability of two new plays by John Logan: I’ll Eat You Last: A Chat with Sue Mengers and Peter and Alice, both published by Oberon Books (London). The three-time Oscar-nominated screenwriter of such films as Skyfall and Hugo returns with two new plays on Broadway and in London’s West End, respectively. I’ll Eat You Last is a one-woman show about legendary Hollywood super-agent Sue Mengers, whose clients included Barbra Streisand, Cher, Gene Hackman and Mike Nichols. Currently on Broadway, starring Bette Midler, I’ll Eat You Last is nominated for the 2013 Drama League awards for Outstanding Production of a Broadway or Off-Broadway Play. Based on the real individuals that inspired J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan and Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, Peter and Alice tells the story of when Alice Liddell Hargreaves met Peter Llewelyn Davies at the opening of a Lewis Carroll exhibition in 1932. Currently playing to acclaim in the West End, Judi Dench stars as Alice and Ben Whishaw as Peter in this new play where enchantment and reality collide. “A delectable soufflé of a solo show… It’s a heady sensation, thanks to the buoyant, witty writing of Mr. Logan… Tangy and funny.” — New York Times on I’ll Eat You Last “A haunting play that sounds profound notes of loss and grief.. -

UC Irvine Journal for Learning Through the Arts

UC Irvine Journal for Learning through the Arts Title Education through Movies: Improving teaching skills and fostering reflection among students and teachers. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2dt7s0zk Journal Journal for Learning through the Arts, 11(1) Authors Blasco, Pablo Gonzalez Moreto, Graziela Blasco, Mariluz González et al. Publication Date 2015 DOI 10.21977/D911122357 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Education through Movies: Improving teaching skills and fostering reflection among students and teachers. Movies are not entertainment. They are a kind of language and reflection. Peter Greenaway. Arts and Emotions to Promote Reflection In life, people learn important attitudes, values, and beliefs using role modeling, a process that impacts the learner’s emotions(1). Certain types of learning have more to do with the affection and love teachers invest in educating people than with theoretical reasoning (2). Usually feelings arise before concepts in the learners. Understanding emotionally through intuition comes in advance. First the heart becomes involved, then rational process clarify the learning issue. Thus the affective path is a critical way to the rational process of learning. While technical knowledge and skills can be acquired through training with little reflection, refining attitudes, acquiring virtues and incorporating values require reflection. In addition to the specific knowledge students must master, learners must refine attitudes, construct identities, develop well- rounded qualities and enrich themselves as human beings. Because people’s emotions play key roles in learning attitudes and behavior, teachers cannot afford to ignore students’ affective domains. To educate through emotions doesn’t mean that learning is limited to values and attitudes exclusively in the affective domain. -

Teaching Social Studies Through Film

Teaching Social Studies Through Film Written, Produced, and Directed by John Burkowski Jr. Xose Manuel Alvarino Social Studies Teacher Social Studies Teacher Miami-Dade County Miami-Dade County Academy for Advanced Academics at Hialeah Gardens Middle School Florida International University 11690 NW 92 Ave 11200 SW 8 St. Hialeah Gardens, FL 33018 VH130 Telephone: 305-817-0017 Miami, FL 33199 E-mail: [email protected] Telephone: 305-348-7043 E-mail: [email protected] For information concerning IMPACT II opportunities, Adapter and Disseminator grants, please contact: The Education Fund 305-892-5099, Ext. 18 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.educationfund.org - 1 - INTRODUCTION Students are entertained and acquire knowledge through images; Internet, television, and films are examples. Though the printed word is essential in learning, educators have been taking notice of the new visual and oratory stimuli and incorporated them into classroom teaching. The purpose of this idea packet is to further introduce teacher colleagues to this methodology and share a compilation of films which may be easily implemented in secondary social studies instruction. Though this project focuses in grades 6-12 social studies we believe that media should be infused into all K-12 subject areas, from language arts, math, and foreign languages, to science, the arts, physical education, and more. In this day and age, students have become accustomed to acquiring knowledge through mediums such as television and movies. Though books and text are essential in learning, teachers should take notice of the new visual stimuli. Films are familiar in the everyday lives of students. -

Central Florida Future, Vol. 40 No. 105, November 19, 2008

University of Central Florida STARS Central Florida Future University Archives 11-19-2008 Central Florida Future, Vol. 40 No. 105, November 19, 2008 Part of the Mass Communication Commons, Organizational Communication Commons, Publishing Commons, and the Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/centralfloridafuture University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Central Florida Future by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation "Central Florida Future, Vol. 40 No. 105, November 19, 2008" (2008). Central Florida Future. 2171. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/centralfloridafuture/2171 - J www.CentralFloridaFuture.com • Wednesday, Nov. 19, 2008 Students of faith The Reformed University • Fellowship students at UCF meet for prayer-SEE NEWS,A2 • Technology • GETTING RICH WITH THE UCF student Jeremy Students to launch next year at NASA facility Lawrence poses with ONE one of the rockets will help the Students for the during the summer and the during a certification The iPhone has become a potential gold SHAWN GAGE flight for the Tripoli mine for entrepreneurs who create Staff Writer Exploration and Development second in December. Rocketry Association . • games for the device.Just ask Steve of Space at UCF propel two According to Keith Lawrence is also working Demeter, developer of the popular puzzle Rockets powered by laugh rockets into the upper atmos Koehler, part of the public with UCF's SEDS to g~me"Trism."The company made the ing gas are no joking matter to phere. -

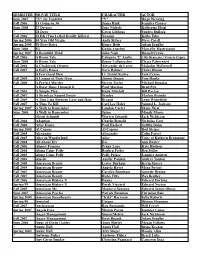

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Sum 2007 "V

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Sum 2007 "V" for Vendetta "V" Hugo Weaving Fall 2006 13 Going on 30 Jenna Rink Jennifer Garner Sum 2008 27 Dresses Jane Nichols Katherine Heigl ? 28 Days Gwen Gibbons Sandra Bullock Fall 2006 2LDK (Two Lethal Deadly Killers) Nozomi Koike Eiko Spring 2006 40 Year Old Virgin Andy Stitzer Steve Carell Spring 2005 50 First Dates Henry Roth Adam Sandler Sum 2008 8½ Guido Anselmi Marcello Mastroianni Spring 2007 A Beautiful Mind John Nash Russell Crowe Fall 2006 A Bronx Tale Calogero 'C' Anello Lillo Brancato / Francis Capra Sum 2008 A Bronx Tale Sonny LoSpeecchio Chazz Palmenteri Fall 2006 A Clockwork Orange Alexander de Large Malcolm McDowell Fall 2007 A Doll's House Nora Helmer Claire Bloom ? A Few Good Men Lt. Daniel Kaffee Tom Cruise Fall 2005 A League of Their Own Jimmy Dugan Tom Hanks Fall 2000 A Perfect Murder Steven Taylor Michael Douglas ? A River Runs Through It Paul Maclean Brad Pitt Fall 2005 A Simple Plan Hank Mitchell Bill Paxton Fall 2007 A Streetcar Named Desire Stanley Marlon Brando Fall 2005 A Thin Line Between Love and Hate Brandi Lynn Whitefield Fall 2007 A Time To Kill Carl Lee Haley Samuel L. Jackson Spring 2007 A Walk to Remember Landon Carter Shane West Sum 2008 A Walk to Remember Jaime Mandy Moore ? About Schmidt Warren Schmidt Jack Nickleson Fall 2004 Adaption Charlie/Donald Nicholas Cage Fall 2000 After Hours Paul Hackett Griffin Dunn Spring 2005 Al Capone Al Capone Rod Steiger Fall 2005 Alexander Alexander Colin Farrel Fall 2005 Alice in Wonderland Alice Voice of Kathryn Beaumont