The Origins of Timber Plantations in India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

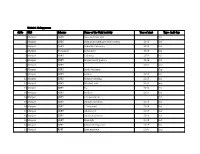

EDUCATIONAL DISTRICT - MALAPPURAM Sl

LIST OF HIGH SCHOOLS IN MALAPPURAM DISTRICT EDUCATIONAL DISTRICT - MALAPPURAM Sl. Std. Std. HS/HSS/VHSS Boys/G Name of Name of School Address with Pincode Block Taluk No. (Fro (To) /HSS & irls/ Panchayat/Muncip m) VHSS/TTI Mixed ality/Corporation GOVERNMENT SCHOOLS 1 Arimbra GVHSS Arimbra - 673638 VIII XII HSS & VHSS Mixed Morayur Malappuram Eranad 2 Edavanna GVHSS Edavanna - 676541 V XII HSS & VHSS Mixed Edavanna Wandoor Nilambur 3 Irumbuzhi GHSS Irumbuzhi - 676513 VIII XII HSS Mixed Anakkayam Malappuram Eranad 4 Kadungapuram GHSS Kadungapuram - 679321 I XII HSS Mixed Puzhakkattiri Mankada Perinthalmanna 5 Karakunnu GHSS Karakunnu - 676123 VIII XII HSS Mixed Thrikkalangode Wandoor Eranad 6 Kondotty GVHSS Melangadi, Kondotty - 676 338. V XII HSS & VHSS Mixed Kondotty Kondotty Eranad 7 Kottakkal GRHSS Kottakkal - 676503 V XII HSS Mixed Kottakkal Malappuram Tirur 8 Kottappuram GHSS Andiyoorkunnu - 673637 V XII HSS Mixed Pulikkal Kondotty Eranad 9 Kuzhimanna GHSS Kuzhimanna - 673641 V XII HSS Mixed Kuzhimanna Areacode Eranad 10 Makkarapparamba GVHSS Makkaraparamba - 676507 VIII XII HSS & VHSS Mixed Makkaraparamba Mankada Perinthalmanna 11 Malappuram GBHSS Down Hill - 676519 V XII HSS Boys Malappuram ( M ) Malappuram Eranad 12 Malappuram GGHSS Down Hill - 676519 V XII HSS Girls Malappuram ( M ) Malappuram Eranad 13 Manjeri GBHSS Manjeri - 676121 V XII HSS Mixed Manjeri ( M ) Areacode Eranad 14 Manjeri GGHSS Manjeri - 676121 V XII HSS Girls Manjeri ( M ) Areacode Eranad 15 Mankada GVHSS Mankada - 679324 V XII HSS & VHSS Mixed Mankada Mankada -

Title: Need to Lay Railway Line Between Nilambur and Nanjangud in Kerala.- Laid

Title: Need to lay railway line between Nilambur and Nanjangud in Kerala.- Laid. *SHRI K. MURALEEDHARAN (CALICUT): Sir, I would like to raise the matter regarding railway development of northern part of Kerala. Not a aingle new railway line has been laid in this area since Independence. The demand for linking Nilambur Road Terminal to Nanjangud Town deserves immediate attention. This proposed link via Wayanad is possible by linking Nilambur to the proposed Nanjangud Sullthan Bathery-Kalpetta-Vythiri-Poozhithode-Badagara line whose survey has already been over. The survey to link this line with Nilambur is yet to be taken up. The Nilambur-Manjeri-Feroke railway line survey is also over. The proposed link from Nilambur to Wayanad via Mundari, covering a distance of just 50 kms. will link Kanyakumari-Trivandrum-Bangalore and Konkan Line. This line will boost the economic development and will also be the shortest rail line between the two industrial cities of Bangalore and Cochin. The district of Wayanad will be linked to the State Capital of Trivandrum by rail. This line will benefit the Sabarimala Pilgrims from Andhra and Karnataka to reach the Sabarimala shrine in the shortest time. This line has immense tourist potential as it would link Bangalore-Srirangapatnam, Mysore, Wayanad, Cochin, Trivandrum and Kanyakumari. The most important point is that this line can serve as an effective by-pass line to the Konkan Line. I sincerely hope that Ministry of Railways would highlight the importance of this vital link between Nilambur and Nanjangud in the broader interest of the nation, as this can cut short the distance between Kashmir and Kanyakumari. -

Ground Water Information Booklet of Alappuzha District

TECHNICAL REPORTS: SERIES ‘D’ CONSERVE WATER – SAVE LIFE भारत सरकार GOVERNMENT OF INDIA जल संसाधन मंत्रालय MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES कᴂ द्रीय भजू ल बो셍 ड CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD केरल क्षेत्र KERALA REGION भूजल सूचना पुस्तिका, मलꥍपुरम स्ज쥍ला, केरल रा煍य GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET OF MALAPPURAM DISTRICT, KERALA STATE तत셁वनंतपुरम Thiruvananthapuram December 2013 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET OF MALAPPURAM DISTRICT, KERALA जी श्रीनाथ सहायक भूजल ववज्ञ G. Sreenath Asst Hydrogeologist KERALA REGION BHUJAL BHAVAN KEDARAM, KESAVADASAPURAM NH-IV, FARIDABAD THIRUVANANTHAPURAM – 695 004 HARYANA- 121 001 TEL: 0471-2442175 TEL: 0129-12419075 FAX: 0471-2442191 FAX: 0129-2142524 GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET OF MALAPPURAM DISTRICT, KERALA TABLE OF CONTENTS DISTRICT AT A GLANCE 1.0 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 1 2.0 CLIMATE AND RAINFALL ................................................................................... 3 3.0 GEOMORPHOLOGY AND SOIL TYPES .............................................................. 4 4.0 GROUNDWATER SCENARIO ............................................................................... 5 5.0 GROUNDWATER MANAGEMENT STRATEGY .............................................. 11 6.0 GROUNDWATER RELATED ISaSUES AND PROBLEMS ............................... 14 7.0 AWARENESS AND TRAINING ACTIVITY ....................................................... 14 -

District: Malappuram Sl.No ULB Scheme Name of the Unit/ Activity

District: Malappuram Sl.No ULB Scheme Name of the Unit/ Activity Year of start Type- Ind/ Grp 1 Manjeri SJSRY Sanu tailoring unit Ind 2 Manjeri SJSRY Stringz kudumbasree (data entry) 2013 Ind 3 Manjeri SJSRY Rahmath stationary 2015 Ind 4 Manjeri Yuvashree Royal store 2015 Ind 5 Manjeri SJSRY Tailoring 2014 Ind 6 Manjeri SJSRY Shalus beauti parlour 2014 Ind 7 Manjeri SJSRY 2017 Grp 8 Manjeri SJSRY Sneha tailoring Grp 9 Manjeri SJSRY Golden 2014 Ind 10 Manjeri SJSRY Tishma tailoring 2015 Ind 11 Manjeri SJSRY Excelant unit 2013 Grp 12 Manjeri SJSRY K s 2014 Ind 13 Manjeri SJSRY Modern 2016 Ind 14 Manjeri SJSRY C h decoration Ind 15 Manjeri SJSRY Athulya furniture 2015 Ind 16 Manjeri SJSRY P l m sound 2014 Ind 17 Manjeri SJSRY Athira toys 2014 Ind 18 Manjeri SJSRY Anoos decoration 2016 Ind 19 Manjeri SJSRY Hair style 2015 Ind 20 Manjeri SJSRY Jalaja tailoring unit 2015 Ind 21 Manjeri RME Jams nutrimix 2006 Grp 22 Manjeri RME Dhanyadhra ayurvedic Ind 23 Manjeri NULM Day care 2018 Ind 24 Manjeri NULM Electrical sale 2018 Ind 25 Manjeri NULM Tailoring 2018 Ind 26 Manjeri NULM Pharmaceuticals 2018 Ind 27 Manjeri NULM Catering unit 2018 Ind 28 Manjeri NULM Santhwanam 2018 Ind 29 Manjeri NULM Day Care 2018 Grp 30 Tanur Own Fund Meenus flour & oil mill 2010 Ind 31 Tanur Own Fund Pavithra vanitha cantein 2015 Grp 32 Tanur Linkage Loan Sangeetha vanitha cantein 2000 Grp 33 Tanur Own Fund Panchami cloth bag 2017 Grp 34 Tanur RME Madurima palaharam 2010 Grp 35 Tanur Own Fund Chembakkam palaharam 2016 Grp 36 Tanur RME Ruchi palaharam 2011 Grp 37 Tanur -

Panchayat/Municipality/Corp Oration

PMFBY List of Panchayats/Municipalities/Corporations proposed to be notified for Rabi II Plantain 2018-19 Season Insurance Unit Sl State District Taluka Block (Panchayat/Municipality/Corp Villages No oration) 1 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Athiyannoor Kanjiramkulam All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 2 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Athiyannoor Karimkulam All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 3 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Athiyannoor Athiyanoor All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 4 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Athiyannoor Kottukal All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 5 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Athiyannoor Venganoor All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 6 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Chirayinkeezhu Kizhuvilam All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 7 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Chirayinkeezhu Mudakkal All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 8 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Chirayinkeezhu Anjuthengu All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 9 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Chirayinkeezhu Chirayinkeezhu All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 10 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Chirayinkeezhu Kadakkavoor All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 11 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Chirayinkeezhu Vakkom All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 12 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Kilimanoor Madavoor All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 13 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Kilimanoor Pallickal All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 14 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Kilimanoor Kilimanoor All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 15 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Kilimanoor Nagaroor All Villages -

Government of Kerala Local Self Government Department

Tribal Development Framework-Social Management Framework July 2020 Kerala Solid Waste Management Project (The World Bank Assisted) GOVERNMENT OF KERALA LOCAL SELF GOVERNMENT DEPARTMENT Public Disclosure Authorized Kerala Solid Waste Management Project Public Disclosure Authorized Tribal Development Framework-Social Management Framework (TDF-SMF) July 2020 VOLUME II PART B Public Disclosure Authorized Project Management Unit Suchithwa Mission Thiruvananthapuram Public Disclosure Authorized 1 Tribal Development Framework-Social Management Framework July 2020 Kerala Solid Waste Management Project (The World Bank Assisted) Table of Contents List of Tables .................................................................................................................................... 8 List of figures ................................................................................................................................... 9 Acronyms ........................................................................................................................................ 10 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................... 14 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 25 1.1 Background .......................................................................................................................... 25 1.2 Project Description ............................................................................................................. -

Regional Transport Authority – Malappuram 7 May 2015

1 REGIONAL TRANSPORT AUTHORITY – MALAPPURAM 7 MAY 2015 AGENDA (PUBLIC) 1. REGULAR STAGE CARRIAGE PERMIT Item No. 1 G2/100796/2013 Agenda (1) To peruse the judgment from Hon. STAT MVAA No. 8/2014; Dtd. 22.01.2015. (2) To re-consider the application for regular Stage Carriage permit to operate on the route Kombankallu Colony – Manjeri Seethi Haji Memorial Bus Stand (via) Kathalakkal Colony, Pookkadi, Perumthura Colony, Perumthura School padi, Kodothkunnu SC Colony, Ucharakadavu Palam, Ucharakadavu, Chanthappadi, Hospital Padi, Melattur, Colony, Edayattur, Valarad Colony, Valarad, Choorakkavu, Pandikkad (also via Olipuzha, Kizhakke Pandikkad), Valluvangad, Nellikuth, Chola, Chengana Bye Pass Jn, Kovilakam kundu, Indira Gandhi Bus Terminal, Kacheripadi, General Hospital, Central Jn, Malamkulam as O.S- Reg. (Vehicle not Offered) Applicant : V. Subrahmannian, S/o Kunhukuttan, Valayangadi House, East Pandikkad, PO Kolaparamba, Manjeri via, Malappuram 676522 Proposed Timings Seethihaji Bus stand IGBT Bus Pandikkad Melattur Kombankallu Colony stand A D A A D A D A D 5.50am 6.15p 6.35 8.00 7.55p 7.25p 7.00 6.40 Edayattur 8.07 8.37p 9.02 9.05 9.25 11.10 11.05p 10.35p 10.05 10.10 9.45 Edayattur 11.15 11.45 12.10p 12.30 Edayattur 1.55 1.50p 1.20p 12.55p 12.35 Edayattur 2.04 2.34p 2.59p 3.19 Edayattur 5.02 4.57p 4.27p 3.55 4.02 3.35 Edayattur 5.15 5.45 6.10p 6.30 Edayattur 8.02 7.57p 7.27p 7.00 7.02 6.40 Edayattur 8.34 9.04p 9.29p 9.49 10.35 10.10p 9.50 halt Edayattur Item No. -

Taluk Village Address 1 Nilambur Edakkara

Final Category catag in which ory in his/ hir which house is the included affect Final in the ed decision Rebuild APP APP perso in Reason for App (if CLA EALE EAL n is appeal Final not in MED D ED includ (Increas Decision the BEF BEF BEF ed ed / (Recommen NAME Rebuild ORE ORE ORE after Reduced ded by the OF App 31/0 31/0 36/0 Appea / No Technically DISASTE Databas 1/20 3/20 6/20 l / Change Competent Relief R RATION e fill the 19 19 19 Reveri / Authority / Assistance SL. AFFECTE CARD colum as (YES (YES (YES ficatio Rejecte Any other Paid or NO TALUK VILLAGE D ADDRESS NUMBER NIL /NO) /NO) /NO) n d) reason) Not Paid KUNJALAVI, Recommende KARTHYAYANI d by the PARAMBIL Technically MUHAMM HOUSE 60- ALLOWE Competent 1 NILAMBUR EDAKKARA ED MANAKKAD 2052132497 NIL yes 74% D Authority PAID Recommende VAKKAYIL d by the HOUSE, Technically VAZHIKKA VAZHIKKADAV 30- ALLOWE Competent 2 NILAMBUR DAVU SAINABA U 2052044416 NIL yes 59% D Authority PAID Recommende d by the Technically VAZHIKKA ANNADAMBAN 205212731 30- ALLOWE Competent 3 NILAMBUR DAVU CHEKU , MARUTHA 6 NIL yes 59% D Authority PAID Recommende KULATHUR d by the HOUSE, Technically KARUVARA DEVADAS KARUVARAKK ALLOWE Competent 4 NILAMBUR KKUNDU AN K UNDU 2052088669 NIL yes 15% D Authority PAID Recommende d by the VELIPPADATH, Technically KARUVARA ARUMUKA KARUVARAKK ALLOWE Competent 5 NILAMBUR KKUNDU N UNDU 2052065736 NIL yes 15% D Authority PAID Compl Recommende ete d by the ERASSERY, loss of Technically KARUVARA PATHUMM KARUVARAKK Buildin ALLOWE Competent 6 NILAMBUR KKUNDU A UNDU NIL yes gs D -

Ground Floor ,Nadar Building No-1371, Trichy Road ,Ciombatore

Sl.No IFSC Code Branch Name District State Branch Address Email Id Contact Number JT Trade Centre, Near X-ray Junction, TSC Road, Alleppy- 1 ESMF0001189 CHERTHALA ALAPUZHA KERALA [email protected] 9656058079 Cherthala Road, Alleppy Dist-688524, Kerala. Kainakari Building Ground Floor & First Floor 15/492D, BL-04/27 GF and 1329 sq feet First floor Near to Power 2 ESMF0001197 ALAPUZHA ALAPUZHA KERALA [email protected] 9633553111 House Shavakottapalam Ernakulam- Alapuzha Road Alapuzha PIN 688007 Geo Commercial Complex, Ground Floor VI/62,63, BL- 3 ESMF0001208 MAVELIKARA ALAPUZHA KERALA 55/17, Mitchel Junction, Haripad- Chengannur Road, [email protected] 8589905454 Mavelikara, PIN-690514 Door No 21/22, Gloria Arcade, Near R K Junction, N H 4 ESMF0001230 HARIPAD ALAPUZHA KERALA [email protected] 8589905709 66, Haripad, Alapuzha, Pin : 690514 Golden House, 820 , 8th Block, Ganapati Temple Road 5 ESMF0001172 KORAMANGALA BANGALORE KARNATAKA [email protected] 9902114807 Koramangla,Bangalore,560034 TRICHY ROAD - Ground Floor ,Nadar Building No-1371, Trichy Road 6 ESMF0001175 COIMBATORE TAMIL NADU [email protected] 7904758925 COIMBATORE ,Ciombatore,641018 38/211 A, Grace Tower, Near Edappally Bye Pass 7 ESMF0001103 EDAPALLY ERNAKULAM KERALA [email protected] 8589969687 Junction, Edappally – Ernakulam 682024 20/1170 A, Near Jacobite Church, Kottayam Road, 8 ESMF0001111 PERUMBAVOOR ERNAKULAM KERALA [email protected] 8589020431 Perumbavoor, Ernakulum 683542. Ground Floor, Pearl tower,Near Signal 9 -

Accused Persons Arrested in Malappuram District from 14.03.2021To20.03.2021

Accused Persons arrested in Malappuram district from 14.03.2021to20.03.2021 Name of Name of Name of Name of the Place at Date & Arresting the Court Sl. Age & Cr. No & Sec Police the father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, at which No. Sex of Law Station Accused Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 ARATTUTHODI 75/2021 U/s BIPIN B 16-03-2021 ABDUL MUHAMME 42, HOUSE, KOOTTILAN 118(i) of KP MALAPPUR NAIR, SI BAILED BY 1 AT 19:10 MAJEED D MALE KAVUNGAL POST, GADI Act, & 6 of AM MALAPPURA POLICE HRS MALAPPURAM COTPA Act M PS 43/2021 U/s 143, 147, 148, ANTICIPAT BIPIN B CHERUPANAKKAD( 20-03- 447, 424, ORY BAIL - SADIQALI.C 34, MALAPPURA MALAPPUR NAIR, SI 2 ABDULLA H),MELMURI(PO),P 2021 AT 323, 353, SESSION .P MALE M PS AM MALAPPURA AITHINIPARAMB 11:00 HRS 332 r/w, 149 COURT M PS IPC & 4(2)(a), MANJERI 4(2)(a) KEDO 43/2021 U/s 143, 147, 148, ANTICIPAT BIPIN B VALLIKKATTUKUN 20-03- 447, 424, ORY BAIL - AHAMMED 32, MALAPPURA MALAPPUR NAIR, SI 3 ALAVIHAJI DIL(H),MUNDUPRA 2021 AT 323, 353, SESSION KABEER MALE M PS AM MALAPPURA MB(PO) 11:30 HRS 332 r/w, 149 COURT M PS IPC & 4(2)(a), MANJERI 4(2)(a) KEDO 43/2021 U/s 143, 147, 148, ANTICIPAT BIPIN B 20-03- 447, 424, ORY BAIL - MUHAMM 32, KADENGAL(H),AD MALAPPURA MALAPPUR NAIR, SI 4 MAMMADU 2021 AT 323, 353, SESSION ED SHAFI MALE HIKARITHODI M PS AM MALAPPURA 11:15 HRS 332 r/w, 149 COURT M PS IPC & 4(2)(a), MANJERI 4(2)(a) KEDO PAROL HOUSE CHERUR PO 20-03- 79/2021 U/s ABOOBACKE DIVAKARA KORUKUTT 43, KOTTEKATTUPARA BAILED BY 5 CHERUR 2021 AT 118(i) -

List of Notified Areas(Panchayats/Muni./Corp) Notified for Paddy ( Autumn ) Kharif 2020,2021 & 2022 Seasons

Annexure PM‐K‐I List of Notified Areas(Panchayats/Muni./Corp) Notified for Paddy ( Autumn ) Kharif 2020,2021 & 2022 Seasons Notified SL No District Block Notified Panchayat List of Villages Crops 1 AMBALAPUZHA AMBALAPUZHA (N) Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayat 2 ALAPPUZHA MUNI. ,PUNNAPRA (N) Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 3 PURAKKAD Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayat 4 AMBALAPUZHA (S) Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayat 5 PUNNAPRA (S) Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayat 6 ARYAD ARYAD ,MANNANCHERY Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 7 MUHAMMA Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayat 8 MARARIKULAM (S) Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayat 9 BHARANIKKAVU MAVELIKARA (MUNI.) Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayat 10 KANJIKUZHY CHERTHALA Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayat 11 CHERTHALA (S) Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayat 12 KANJIKUZHI Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayat 13 THANNEERMUKKOM Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayat 14 KADAKKARAPPALLY Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayat 15 MARARIKULAM (N) Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayat 16 PATTANAKKAD AROOR Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayat 17 KODAMTHURUTH Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayat 18 PATTANAKKAD Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayat 19 EZHUPUNNA Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayat 20 KUTHIYATHODE Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayat 21 THURAVOOR Paddy All Villages in the Notified Panchayat 22 VAYALAR Paddy -

MALAPPURAM District, Kerala

Coconut Producers Federations (CPF) - MALAPPURAM District, Kerala Sl No.of No.of Bearing Annual CPF Reg No. Name of CPF and Contact address Panchayath Block Taluk No. CPSs farmers palms production AREACODE PANJAYATH FEDERATION OF COCONUT PRODUCERS SOCIETY President: Shri Sadikali P 1 CPF/MPM/2014-15/065 Areacode Areacode Eranad 8 361 40929 2700474 Kaithayil House, Near I.T.I., Ugrappuram P.O Pin:673639 Mobile:9846612772 NARAGIL FEDERATION OF COCONUT PRODUCERS 2 CPF/MPM/2015-16/089 SOCIETIES President: Shri A P Muhammed A.P.B Areacode Areacode Eranad 8 702 40003 2055765 House, Areecode, Areecode PO Pin:673639 CHEEKODE GRAMA PANCHAYATH FEDERATION OF COCONUT PRODUCERS SOCIETY President: Shri 3 CPF/MPM/2012-13/015 Cheekode Areacode Eranad 19 1292 81524 10198245 Sainudheen K P Puiyamakal House, Cheriayaparambu P.O., Vilayil, Malapuram Pin:673641 Mobile:9846162666 EDAVANNA GRAMA PANCHAYAT FEDERATION OF COCONUT PRODUCERS SOCIETY President: Shri K 4 CPF/MPM/2013-14/029 Edavanna Areacode Eranad 10 653 41348 3424275 Muhammed Kallingal (H), Edavanna (PO), Malappuram Pin:676541 Mobile:9895224606 ERANAD FEDERATION OF COCONUT PRODUCING SOCIETY President: Shri Ahammed Kutty Athikkal 5 CPF/MPM/2014-15/079 Edavanna Areacode Eranad 13 854 56689 3673770 House, Kunnummal, Edavanna PO Pin:676541 Mobile:9946274616 KAVANUR GRAMA PANCHAYAT FEDERATION OF COCONUT PRODUCERS SOCIETY President: Shri M P 6 CPF/MPM/2013-14/030 Kavannur Areacode Eranad 14 908 59559 6601335 Saidalavi Panampattachalil (H), Erivetty (PO), Kavanur, Malappuram Pin:673639 Mobile:9446215455