The Murids of Senegal in New York Angelia R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Challenge of African Art Music Le Défi De La Musique Savante Africaine Kofi Agawu

Document généré le 30 sept. 2021 18:33 Circuit Musiques contemporaines The Challenge of African Art Music Le défi de la musique savante africaine Kofi Agawu Musiciens sans frontières Résumé de l'article Volume 21, numéro 2, 2011 Cet article livre des réflexions générales sur quelques défis auxquels les compositeurs africains de musique de concert sont confrontés. Le point de URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1005272ar départ spécifique se trouve dans une anthologie qui date de 2009, Piano Music DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1005272ar of Africa and the African Diaspora, rassemblée par le pianiste et chercheur ghanéen William Chapman Nyaho et publiée par Oxford University Press. Aller au sommaire du numéro L’anthologie offre une grande panoplie de réalisations artistiques dans un genre qui est moins associé à l’Afrique que la musique « populaire » urbaine ou la musique « traditionnelle » d’origine précoloniale. En notant les avantages méthodologiques d’une approche qui se base sur des compositions Éditeur(s) individuelles plutôt que sur l’ethnographie, l’auteur note l’importance des Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal rencontres de Steve Reich et György Ligeti avec des répertoires africains divers. Puis, se penchant sur un choix de pièces tirées de l’anthologie, l’article rend compte de l’héritage multiple du compositeur africain et la façon dont cet ISSN héritage influence ses choix de sons, rythmes et phraséologie. Des extraits 1183-1693 (imprimé) d’oeuvres de Nketia, Uzoigwe, Euba, Labi et Osman servent d’illustrations à cet 1488-9692 (numérique) article. Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Agawu, K. -

Theminorityreport

theMINORITYREPORT The annual news of the AEA’s Committee on the Status of Minority Groups in the Economics Profession, the National Economic Association, and the American Society of Hispanic Economists Issue 11 | Winter 2019 Nearly a year after Hurricane Maria brought catastrophic PUERTO RICAN destruction across the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico on September 20, 2017, the governor of Puerto Rico MIGRATION AND raised the official death toll estimate from 64 to 2,975 fatalities based on the results of a commissioned MAINLAND report by George Washington University’s Milken Institute School of Public Health (2018). While other SETTLEMENT independent reports (e.g., Kishore et al. 2018) placed the death toll considerably higher, this revised estimate PATTERNS BEFORE represented nearly a tenth of a percentage point (0.09 percent) of Puerto Rico’s total population of 3.3 million AND AFTER Americans—over a thousand more deaths than the estimated 1,833 fatalities caused by Hurricane Katrina in HURRICANE MARIA 2005. Regardless of the precise number, these studies consistently point to many deaths resulting from a By Marie T. Mora, University of Texas Rio Grande lack of access to adequate health care exacerbated by the collapse of infrastructure (including transportation Valley; Alberto Dávila, Southeast Missouri State systems and the entire electrical grid) and the severe University; and Havidán Rodríguez, University at interruption and slow restoration of other essential Albany, State University of New York services, such as running water and telecommunications. -

The Festival of American Folklife: Building on Tradition Richard Kurin

The Festival of American Folklife: Building on Tradition Richard Kurin This summer marks the 25th annual Festival of Mary McGrory, then a reporter for The Evening American Folklife. Over the years more than Star, wrote, 16,000 musicians, dancers, craftspeople, storytell Thanks to S. Dillon Ripley, Secretary of the ers, cooks, workers, and other bearers of tradi Smithsonian Institution, thousands of tional culture from every region of the United people have been having a ball on the States and every part of the globe have come to Mall, watching dulcimer-makers, quilters, the National Mall in Washington to illustrate the potters and woodcarvers and listing to art, knowledge, skill and wisdom developed music. "My thought," said Ripley, "is that within their local communities. They have sung we have dulcimers in cases in the mu and woven, cooked and danced, spun and seum, but how many people have actually stitched a tapestry of human cultural diversity; heard one or seen one being made?" they have aptly demonstrated its priceless value. Their presence has changed the National Mall During the mid-1960s the Smithsonian Institu and the Smithsonian Institution. Their perform tion re-evaluated its approach to understanding ances and demonstrations have shown millions and interpreting American culture and its atten of people a larger world. And their success has dant institutional responsibilities. Secretary Ripley encouraged actions, policies and laws that pro reported his initiative to mount the first Festival mote human cultural rights. The Festival has been to the Board of Regents, the Smithsonian's gov a vehicle for this. And while it has changed in erning body, in February, 1967: various ways over the years, sometimes only to A program sponsored by the Smithsonian change back once again, the Festival's basic pur should reflect the Institution's founding pose has remained the same. -

DOCUMENT RESUME Immigration and Ethnic Communities

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 413 156 RC 021 296 AUTHOR Rochin, Refugio I., Ed. TITLE Immigration and Ethnic Communities: A Focus on Latinos. INSTITUTION Michigan State Univ., East Lansing. Julian Samora Research Inst. ISBN ISBN-0-9650557-0-1 PUB DATE 1996-03-00 NOTE 139p.; Based on a conference held at the Julian Samora Research Institute (East Lansing, MI, April 28, 1995). For selected individual papers, see RC 021 297-301. PUB TYPE Books (010)-- Collected Works General (020) -- Information Analyses (070) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Demography; Elementary Secondary Education; Employment; Ethnic Bias; Hispanic Americans; *Immigrants; Immigration; *Labor Force; Mexican American Education; *Mexican Americans; Mexicans; Migrant Workers; Politics of Education; *Socioeconomic Status; Undocumented Immigrants IDENTIFIERS California; *Latinos; *Proposition 187 (California 1994); United States (Midwest) ABSTRACT For over a decade, Latino immigrants, especially those of Mexican origin, have been at the heart of the immigration debate and have borne the brunt of conservative populism. Contributing factors to the public reaction to immigrants in general and Latinos specifically include the sheer size of recent immigration, the increasing prevalence of Latinos in the work force, and the geographic concentration of Latinos in certain areas of the country. Based on a conference held at the Julian Samora Institute(Michigan) in April 1995, this book is organized around two main themes. The first discusses patterns of immigration and describes several immigrant communities in the United States; the second looks in depth at immigration issues, including economic impacts, employment, and provision of education and other services to immigrants. Papers and commentaries are: (1) "Introductory Statement" (Steven J. -

Young Senegalese-Americans' Experiences of Growing Up

Mobility, social reproduction and triple minority status: young Senegalese-Americans’ experiences of growing up transnationally Hannah Hoechner, University of East Anglia [email protected] A growing body of literature explores how transnational migration from Africa to Western countries affects childrearing practices. While the motivations and constraints underpinning parents’ decisions to raise children partly or entirely in the ‘homeland’ are fairly well documented, much less is known about young people’s experiences of transnational mobility and about its relationship to social reproduction. Drawing on data collected over 14 months among Senegalese migrant communities in New York and New Jersey, and in Islamic schools receiving migrants’ children in Dakar, Senegal, this paper explores how educational stints in the ‘homeland’ equip young people with cultural and religious resources to deal with the challenges of living in the US as part of a triple minority as Blacks, immigrants, and Muslims. At the same time, homeland stays produce a series of new vulnerabilities, as young people struggle to adjust to an unfamiliar language and disciplinary regime in the US. Keywords: Transnational families, social reproduction, West Africa, transnational migration, Islamic education Introduction Fatou’s small flat in a five-storey Harlem apartment block is always lively with people.1 The first time I visit, her two-year-old, an energetic little boy, keeps racing through the living room. Fatou sighs that he is turning the flat upside down! Senegal has gotten him too used to having space to run – and she bets her relatives spoiled him rotten! That is what you get in return for sending them to visit, she laments. -

Lost Wax: an Exploration of Bronze Sculpture in Senegal Kevin Bell SIT Study Abroad

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2009 Lost Wax: An Exploration of Bronze Sculpture in Senegal Kevin Bell SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Art Practice Commons Recommended Citation Bell, Kevin, "Lost Wax: An Exploration of Bronze Sculpture in Senegal" (2009). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 735. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/735 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lost Wax: An Exploration of Bronze Sculpture in Senegal Bell, Kevin Academic Director: Diallo, Souleye Project Advisor: Diop, Issa University of Denver International Studies Africa, Senegal, Dakar Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Senegal Arts and Culture, SIT Study Abroad, Fall 2009 Table of Contents ABSTRACT: ................................................................................................................................................................1 I. LEARNING GOALS: .........................................................................................................................................2 I. RESOURCES AND METHODS: ......................................................................................................................3 -

Losing Or Securing Futures? Looking Beyond 'Proper'

Children's Geographies ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cchg20 Losing or securing futures? Looking beyond ‘proper’ education to decision-making processes about young people’s education in Africa – an introduction Tabea Häberlein & Sabrina Maurus To cite this article: Tabea Häberlein & Sabrina Maurus (2020) Losing or securing futures? Looking beyond ‘proper’ education to decision-making processes about young people’s education in Africa – an introduction, Children's Geographies, 18:6, 569-583, DOI: 10.1080/14733285.2019.1708270 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2019.1708270 © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 11 Nov 2020. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cchg20 CHILDREN’S GEOGRAPHIES 2020, VOL. 18, NO. 6, 569–583 https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2019.1708270 INTRODUCTION Losing or securing futures? Looking beyond ‘proper’ education to decision-making processes about young people’s education in Africa – an introduction Tabea Häberleina and Sabrina Maurusb aSocial Anthropology, University of Bayreuth, Bayreuth, Germany; bAfrica Multiple Cluster of Excellence, Research Section Learning, University of Bayreuth, Bayreuth, Germany ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY The education of young people in Africa has been receiving increasing Received 19 November 2019 political attention due to expanded schooling and, as a result, an Accepted 3 December 2019 expanding number of unemployed educated youths who challenge KEYWORDS governments. While many studies have described young people in Education; youth; Africa; Africa as being in a stage of ‘waithood’, this special issue looks at ’ schooling; future; decision- decision-making processes in youths education. -

In America: Exploring Racial Identity Development of African Immigrants

Minnesota State University, Mankato Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato All Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Other Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects Capstone Projects 2012 Becoming "Black" in America: Exploring Racial Identity Development of African Immigrants Godfried Agyeman Asante Minnesota State University, Mankato Follow this and additional works at: https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/etds Part of the African Studies Commons, Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons, and the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Asante, G. A. (2012). Becoming "Black" in America: Exploring racial identity development of African immigrants. [Master’s thesis, Minnesota State University, Mankato]. Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/etds/43/ This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects at Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. Becoming “Black” in America: Exploring Racial Identity Development of African Immigrants By Godfried Agyeman Asante A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MA In Communication Studies Minnesota State University, Mankato, Mankato, Minnesota April 2012 2 Becoming “Black” in America: Exploring Racial Identity Development of African Immigrants Godfried Agyeman Asante This thesis has been examined and approved by the following members of the thesis committee Dr. -

Five Takes on African Art a Study Guide

FIVE TAKES ON AFRICAN ART A STUDY GUIDE TAKE 1 considers materiality, and the elements used to make aesthetic objects. It also considers the connections that materials have to the people who originally crafted them, and furthermore, their ties to new generations of crafters, interpreters, and collectors of African works. The objects in this collection challenge our notions of “African art” in that they were not formed for purely aesthetic purposes, but rather were created from raw, natural materials, carefully refined, and then skillfully handcrafted to serve particular needs in homes and communities. It is fascinating to consider that each object featured here bears a characteristic that identifies it as belonging to a distinct region or group of people, and yet is nearly impossible to unearth the narratives of the individual artists who created them. Through these works, we can consider the bridge between materiality and diaspora—objects of significance with “genetic codes” that move from one hand to the next, across borders, and oceans, with a dynamism that is defined by our ever-shifting world. Here, these “useful” objects take on a new function, as individual parts to an entire chorus of voices—each possessing a unique story in its creation and journey. What makes these objects ‘collectors’ items’? Pay close attention to the shapes, forms, and craftsmanship. Can you find common traits or themes? The curator talks about their ‘genetic codes’. Beside the object’s substance, specific to the location of its creation, it may carry traces of other accumulated materials, such as food, skin, fiber, or fluids. -

Living Arrangements of Older Persons Around the World

April 2019 No. 2019/2 Living arrangements of older persons around the world ousehold living arrangements of persons aged 65 2. Living arrangements of older persons vary years or over are an important factor associated greatly across countries and regions Hwith the health, economic status and well-being of older persons.1 While some older persons live alone, others Across the 137 countries or areas with available data, living reside with a spouse or a partner, or with their children arrangements of persons aged 65 years or older differed or grandchildren in multi-generational households. markedly, reflecting differences in family size and personal Understanding the patterns and trends in the living behaviours that were influenced by social and cultural arrangements of older persons is relevant for global efforts norms as well as economic conditions. to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), in particular Goal 1 on poverty, Goal 2 on hunger and Goal 3 Living with a child or with extended family members on health. In 2002, the Madrid International Plan of Action was the most common living arrangement among on Ageing identified older persons’ living arrangements as older persons in Africa, Asia and Latin America and a topic requiring more research and attention.2 the Caribbean, whereas in Europe, Northern America, Australia and New Zealand, living with a spouse only was This brief summarizes selected key findings from a recent the most common arrangement, followed by living alone. analysis of the size and composition of households with For example, in Afghanistan and Pakistan, more than 90 at least one older person, using the latest edition of per cent of persons aged 65 years or over co-resided with the United Nations Database on Household Size and their children or lived with extended family members and Composition 2018.3 fewer than 1 per cent lived alone. -

Contemporary Africa Arts

CONTEMPORARY AFRICAN ARTS MAPPING PERCEPTIONS, INSIGHTS AND UK-AFRICA COLLABORATIONS 2 CONTENTS 1. Key Findings 4 2. Foreword 6 3. Introduction 8 4. Acknowledgements 11 5. Methodology 12 6. What is contemporary African arts and culture? 14 7. How do UK audiences engage? 16 8. Essay: Old Routes, New Pathways 22 9. Case Studies: Africa Writes & Film Africa 25 10. Mapping Festivals - Africa 28 11. Mapping Festivals - UK 30 12. Essay: Contemporary Festivals in Senegal 32 13. What makes a successful collaboration? 38 14. Programming Best Practice 40 15. Essay: How to Water a Concrete Rose 42 16. Interviews 48 17. Resources 99 Cover: Africa Nouveau - Nairobi, Kenya. Credit: Wanjira Gateri. This page: Nyege Nyege Festival - Jinja, Uganda. Credit: Papashotit, commissioned by East Africa Arts. 3 1/ KEY FINDINGS We conducted surveys to find out about people’s perceptions and knowledge of contemporary African arts and culture, how they currently engage and what prevents them from engaging. The first poll was conducted by YouGov through their daily online Omnibus survey of a nationally representative sample of 2,000 adults. The second (referred to as Audience Poll) was conducted by us through an online campaign and included 308 adults, mostly London-based and from the African diaspora. The general British public has limited knowledge and awareness of contemporary African arts and culture. Evidence from YouGov & Audience Polls Conclusions Only 13% of YouGov respondents and 60% of There is a huge opportunity to programme a much Audience respondents could name a specific wider range of contemporary African arts and example of contemporary African arts and culture, culture in the UK, deepening the British public’s which aligned with the stated definition. -

Au Echo 2021 1 Note from the Editor

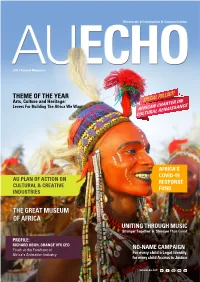

Directorate of Information & Communication 2021 Annual Magazine THEME OF THE YEAR Arts, Culture and Heritage: Levers For Building The Africa We Want AFRICAN CHARTER ON CULTURAL RENAISSANCE AFRICA’S COVID-19 AU PLAN OF ACTION ON RESPONSE CULTURAL & CREATIVE FUND INDUSTRIES THE GREAT MUSEUM OF AFRICA UNITING THROUGH MUSIC ‘Stronger Together’ & ‘Stronger Than Covid’ PROFILE: RICHARD OBOH, ORANGE VFX CEO Youth at the Forefront of NO-NAME CAMPAIGN Africa’s Animation Industry For every child a Legal Identity, for every child Access to Justice www.au.int AU ECHO 2021 1 NOTE FROM THE EDITOR he culture and creative industries (CCIs) generate annual global revenues of up to US$2,250 billion dollars and Texports in excess of US$250 billion. This sector currently provides nearly 30 million jobs worldwide and employs more people aged 15 to 29 than any other sector and contributes LESLIE RICHER up to 10% of GDP in some countries. DIRECTOR Directorate of Information & In Africa, CCIs are driving the new economy as young Africans Communication tap into their unlimited natural resource and their creativity, to create employment and generate revenue in sectors traditionally perceived as “not stable” employment options. taking charge of their destiny and supporting the initiatives to From film, theatre, music, gaming, fashion, literature and art, find African solutions for African issues. On Africa Day (25th the creative economy is gradually gaining importance as a May), the African Union in partnership with Trace TV and All sector that must be taken seriously and which at a policy level, Africa Music Awards (AFRIMA) organised a Virtual Solidarity decisions must be made to invest in, nurture, protect and grow Concert under the theme ‘Stronger Together’ and ‘Stronger the sectors.