Whether It Is Bollywood Or Hollywood, There Is No Doubt That Films Are the Dominant Story-Telling Medium Since the Late 20Th C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animation: Types

Animation: Animation is a dynamic medium in which images or objects are manipulated to appear as moving images. In traditional animation, images are drawn or painted by hand on transparent celluloid sheets to be photographed and exhibited on film. Today most animations are made with computer generated (CGI). Commonly the effect of animation is achieved by a rapid succession of sequential images that minimally differ from each other. Apart from short films, feature films, animated gifs and other media dedicated to the display moving images, animation is also heavily used for video games, motion graphics and special effects. The history of animation started long before the development of cinematography. Humans have probably attempted to depict motion as far back as the Paleolithic period. Shadow play and the magic lantern offered popular shows with moving images as the result of manipulation by hand and/or some minor mechanics Computer animation has become popular since toy story (1995), the first feature-length animated film completely made using this technique. Types: Traditional animation (also called cel animation or hand-drawn animation) was the process used for most animated films of the 20th century. The individual frames of a traditionally animated film are photographs of drawings, first drawn on paper. To create the illusion of movement, each drawing differs slightly from the one before it. The animators' drawings are traced or photocopied onto transparent acetate sheets called cels which are filled in with paints in assigned colors or tones on the side opposite the line drawings. The completed character cels are photographed one-by-one against a painted background by rostrum camera onto motion picture film. -

Indian Entertainment and Media Outlook 2010 2 Indian Entertainment and Media Outlook 2010 Message

Indian entertainment and media outlook 2010 2 Indian entertainment and media outlook 2010 Message To our clients and friends both in and beyond the entertainment and media industry : Welcome to the 2010 edition of PricewaterhouseCoopers’ Indian Entertainment and Media (E&M) Outlook, covering the forecast period of 2010–2014. Our forecasts and analysis for this edition focus on eight major E&M industry segments and one emerging segment. Each segment details out the key trends observed and challenges faced apart from providing the prospects for the segment. In the industry overview section, we have highlighted the key theme observed during 2009 and what we perceive as future trends in the coming years. We have a chapter on the tax and regulatory impact on the various E&M segments and for the very first time we have included a chapter on how technology can be leveraged in the E&M industry. In 2009, the economy severely impacted the world, translating into steep declines in advertisement as well as consumer spending. India though impacted, did manage to show growth with increased consumer spending as well as innovative action on the part of the industry. Against this backdrop, across the world, except certain markets, speed of digital spending increased due to changing consumer behavior as well as technology available to deliver the same. In India, while the spend on digital media is likely to grow, it is unlikely that it will dominate in the forecast period. This is largely due to the relative unavailability as well as unaffordability of the broadband and mobile infrastructure. -

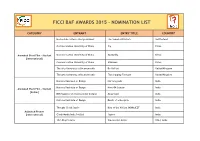

Ficci Baf Awards 2015 - Nomination List

FICCI BAF AWARDS 2015 - NOMINATION LIST CATEGORY ENTRANT ENTRY TITLE COUNTRY Hochschule Luzern - Design & Kunst The Sound of Crickets Switzerland Communication University of China Fly China Animated Short Film - Student Communication University of China My Daddy China [International] Communication University of China HideSeek China The Arts University at Bournemouth Do Us Part United Kingdom The Arts University at Bournemouth The Shipping Forecast United Kingdom National Institute of Design Her long nails India National Institute of Design Horn Ok Scream India Animated Short Film - Student [Indian] DSK Supinfocom International Campus Magarwasi India National Institute of Design Death of a Mosquito India Thought Cloud Studio Rise of the Valiant INDRAJEET India Animated Promos [International] Climb Media India Pvt Ltd Jugnoo India 19th Day Pictures Vincent the Artist USA | India Thought Cloud Studio Rise of the Valiant INDRAJEET India Animated Promos [Indian] Climb Media India Pvt Ltd Jugnoo India Nestle | Paperboat Design Studios Pvt Ltd Superbabies India Climb Media India Pvt Ltd BSE Fishing India Animated Ad Film Mit Institute of Design ICRC India [International] Syu Design BSE APP India Studio Eeksaurus Productions Pvt Ltd Rotary Lifeline India Studio Eeksaurus Productions Pvt Ltd Rotary Heartline India Animated Ad Film [Indian] Studio Eeksaurus Productions Pvt Ltd Rotary Fateline India FutureWorks Integrated Advertising | Welspun-world of hygrocotton India Futureworks Media Ltd Studio Eeksaurus Productions Pvt Ltd Fisherwoman and Tuk Tuk India Animated Short Film - Professional Mud n Water Production Pvt Ltd Talking Walls India [International] Aroop Dwivedi Aai India Studio Eeksaurus Productions Pvt Ltd Fisherwoman and Tuk Tuk India Animated Short Film - Professional Figment Films Sonali Pakhi India [Indian] Mud n Water Production Pvt Ltd Talking Walls India Bluepixels Animation Studios Pvt Ltd Ande Pirki India Studio 100 | Visual Computing Labs - Tata Heidi Belgium | India Animated TV Episode Elxsi Ltd. -

Stop-Motion Animation an Introduction What Is Animation?

Stop-motion Animation An Introduction What is Animation? In its simplest form, animation is essentially making something that doesn’t move (inanimate) look like it is moving (animate). This can be done through repeated drawings or paintings (traditional 2D), using puppets or clay (stop-motion) and using computer programmes and software (CG and 3D). All of these methods have one aim in mind: to create ‘the illusion of life’. Key Resource: The Evolution of Animation The following video shows how animation has evolved from it’s very first days using contraptions like the ‘Zoetrope’. Whilst you watch these clips, think about the different types of animation used. How many of these films do you recognise? The Evolution of Animation 1833-2017 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z6TOQzCDO7Y Many older animations are available to watch on Youtube, such as ‘Gertie the Dinosaur’ and ‘Felix the Cat’, and it’s important to appreciate these as being the roots of modern animation. Younger Animators might also get a kick out of watching some classic ‘Looney Tunes’ cartoons. What is movement? A movement is when something goes from point A to point B in a certain amount of time. The amount of time it takes dictates how fast that movement is. In other words, if something goes from point A to B in a short amount of time then it is a fast movement, and if it takes a long time then it is a slow movement. Experiment: Try out some actions like waving, spinning in a circle and walking all at different speeds. -

2016 FEATURE FILM STUDY Photo: Diego Grandi / Shutterstock.Com TABLE of CONTENTS

2016 FEATURE FILM STUDY Photo: Diego Grandi / Shutterstock.com TABLE OF CONTENTS ABOUT THIS REPORT 2 FILMING LOCATIONS 3 GEORGIA IN FOCUS 5 CALIFORNIA IN FOCUS 5 FILM PRODUCTION: ECONOMIC IMPACTS 8 6255 W. Sunset Blvd. FILM PRODUCTION: BUDGETS AND SPENDING 10 12th Floor FILM PRODUCTION: JOBS 12 Hollywood, CA 90028 FILM PRODUCTION: VISUAL EFFECTS 14 FILM PRODUCTION: MUSIC SCORING 15 filmla.com FILM INCENTIVE PROGRAMS 16 CONCLUSION 18 @FilmLA STUDY METHODOLOGY 19 FilmLA SOURCES 20 FilmLAinc MOVIES OF 2016: APPENDIX A (TABLE) 21 MOVIES OF 2016: APPENDIX B (MAP) 24 CREDITS: QUESTIONS? CONTACT US! Research Analyst: Adrian McDonald Adrian McDonald Research Analyst (213) 977-8636 Graphic Design: [email protected] Shane Hirschman Photography: Shutterstock Lionsgate© Disney / Marvel© EPK.TV Cover Photograph: Dale Robinette ABOUT THIS REPORT For the last four years, FilmL.A. Research has tracked the movies released theatrically in the U.S. to determine where they were filmed, why they filmed in the locations they did and how much was spent to produce them. We do this to help businesspeople and policymakers, particularly those with investments in California, better understand the state’s place in the competitive business environment that is feature film production. For reasons described later in this report’s methodology section, FilmL.A. adopted a different film project sampling method for 2016. This year, our sample is based on the top 100 feature films at the domestic box office released theatrically within the U.S. during the 2016 calendar -

In India, Gods Rule the 'Toon' Universe

In India, Gods Rule The 'Toon' Universe http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2008/01/08/AR... In India, Gods Rule The 'Toon' Universe Hindu Myth a Fount of Superheroes By Rama Lakshmi Washington Post Foreign Service Wednesday, January 9, 2008; A11 NEW DELHI -- Eight-year-old Tejas Vohra is used to spending most of his after-school hours watching "Power Rangers," "Transformers" and "Looney Tunes." But these days, one of his favorite superheroes is a cool cartoon version of Hanuman, the monkey-headed Hindu god. For thousands of years, Hindus have prayed to Hanuman in times of trouble, beseeching him to perform miraculous feats in their lives. Last week, the god was revealed to Tejas in a movie theater. In "The Return of Hanuman," the adored deity is reborn as a boy who goes to school in khaki shorts, uses a computer, combats pollution and, most important, smashes the bad guys to pulp. "I loved the film because Hanuman is a boy like me and saves planet Earth," said Tejas, a tall, wide-eyed second-grader. "It was awesome to see the gods laughing, singing and flying planes. The fights were really good, and in the end Hanuman sets everything right." A number of haloed Hindu gods and goddesses have debuted in the frenetic world of animation over the past five years. Their appearance marks a shift from a decades-long period in which Indian children grew up almost exclusively on American TV and movie characters, including Mickey Mouse, Tom and Jerry, and Spider-Man. To many parents, though, the "mytho-cartoons" are more than a novelty; they are a way to introduce the ancient tales to a generation that seems to be losing touch with its 5,000-year heritage. -

The Power of Storytelling

The Power of Storytelling Using a story to create a coherent experience from conception to execution FIRST®STEAMWORKSSM invites two adventurers’ clubs, in an era where steam power reigns, to prepare their airships for a long distance race. Each three-team alliance prepares in three ways: 1. Build steam pressure. Robots collect fuel (balls) and score it in their boiler via high and low efficiency goals. Boilers turn fuel into steam pressure which is stored in the steam tank on their airship – but it takes more fuel in the low efficiency goal to build steam than the high efficiency goal. 2. Start rotors. Robots deliver gears to pilots on their airship for installation. Once the gear train is complete, they turn the crank to start the rotor. 3. Prepare for flight. Robots must latch on to their airship before launch (the end of the match) by ascending their The Story of FIRST ropesto signal that they’re ready for Steamworks takeoff. Game Manual Fonts and Images • Header used steamworks inspired images • Color palette was pulled from logo colors • Font was selected from Steampunk artwork* *Shout out to Hananiah Wilson and FRC Team 4534, the Wired Wizards, from Wilmington, NC, USA for creating an amazing style guide that we used. Field Design: Airships The story said airships, but what did they look like? • Simulate flight • Large enough for human players • Interactive for human players and robots • Game piece transfer from robot to making the airship function Concept art for possible airship designs Field Design: Airships Gear implementation concept art Concept art for gear implementation. -

Srijan Digital Arts

REPORT ON PROMOTION AND AWARENESS OF STUDIO: SRIJAN DIGITAL ARTS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Award of the degree of BACHELOR OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION (2009-2012) SUBMITTED TO: - SUBMITTED BY:- EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Business Administration Project has been undertaken to study the international market of Multimedia/Animation industry and to analyze comprehensively the Indian Market scenario. The research study was conducted to find out the factors which would influence the major developments taking place in this industry, at both the global as well as domestic level. With these objectives in mind, the information is collected from various publications related with this industry, websites, Government institutions and other secondary sources. Later on all this information was compiled in the form of presentable and highly comprehensible report. The important outcomes are: • The Multimedia/Animation industry is highly fragmented. • India is the fastest growing Multimedia/Animation industry. 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Every work constitutes great deal of assistance and guidance from the people concerned and this particular project is of no exception. A project of the nature is surely a result of tremendous support, guidance, encouragement and help. Wish to place on record my sincere gratitude to Mr. XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX I thank him for constructive help and encouragement throughout the project. Without his support and guidance taking this would not have been possible. Also, wish to acknowledge enthusiastic encouragement and support extended to me by my family members. At last, I would like to thank all the faculty of business management to help me completing this project. Im also thankful to my friends who provided me their constant support and assistance. -

Arjun: the Warrior Prince Invades Bollywood and Hollywood Visual Computing Labs Delivers Its Second Animated Feature Film In

Tata Elxsi-VCL Arjun: The Warrior Prince Invades www.tataelxsi.com/vcl Bollywood and Hollywood Mumbai, India Visual Computing Labs delivers its Autodesk® Maya® software Autodesk® 3ds Max® software second animated feature film in record Autodesk® Flame® software time using Autodesk® Maya® “From the very beginning, our ambition with Arjun: The Warrior Prince was to create a work of art that would visually transcend other animated Bollywood films created to date. The nature of the story calls for several challenging action scenes that feature breathtaking backdrops, chariot races and battle sequences. To make those appear rich and hyper- real, we relied heavily on Maya; it was our first choice and a natural fit Image courtesy of Tata Elxsi-VCL for the job – giving us all Summary between Walt Disney Animation Studios and UTV Founded in 2001, Visual Computing Labs (VCL) Pictures, Arjun: The Warrior Prince was released of the tools necessary is the visual effects and gaming arm of Tata Elxsi in movie theatres on May 25, 2012. Directed by to deliver the lush, Ltd., part of the multibillion-dollar Tata Group, Arnab Chaudhuri, the film features the vocal talents dynamic backgrounds and and a leading Indian animation and visual effects of Yudhveer Bakolia, Anjan Srivastava, Sachin powerhouse. Over the last 11 years, VCL has Khedekar, Ila Arun and Hemant Mahaur. characters that carry the contributed effects to a number of award-winning story.” films, TV programs and commercials. Operating out The Challenge of two offices, the company has studios in Santa Arjun: The Warrior Prince is an animated —Vishal Anand Monica, California and Mumbai — both supported mythological action film that recounts the untold by teams of phenomenally talented artists. -

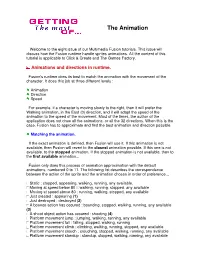

The Animation

The Animation Welcome to the eight issue of our Multimedia Fusion tutorials. This issue will discuss how the Fusion runtime handle sprites animations. All the content of this tutorial is applicable to Click & Create and The Games Factory. Animations and directions in runtime. Fusion's runtime does its best to match the animation with the movement of the character. It does this job at three different levels : Animation Direction Speed For example, if a character is moving slowly to the right, then it will prefer the Walking animation, in the East (0) direction, and it will adapt the speed of the animation to the speed of the movement. Most of the times, the author of the application does not draw all the animations, or all the 32 directions. When this is the case, Fusion has to approximate and find the best animation and direction possible. Matching the animation. If the exact animation is defined, then Fusion will use it. If this animation is not available, then Fusion will revert to the closest animation possible. If this one is not available, to the stopped animation. If the stopped animation is not available, then to the first available animation... Fusion only does this process of animation approximation with the default animations, numbered 0 to 11. The following list describes the correspondance between the action of the sprite and the animation chosen in order of preference... Static : stopped, appearing, walking, running, any available. Moving at speed below 80 :: walking, running, stopped, any available Moving at speed above -

Toonz Animation India Private Limited

Toonz Animation India Private Limited https://www.indiamart.com/toonz-animation/ Established in the year 1999, Toonz Animation India Pvt. Ltd is the state-of-the-art animation production facility of Toonz group. The 18,000 sq feet facility is nestled in Technopark, India's largest IT Park located in the South Indian state of ... About Us Established in the year 1999, Toonz Animation India Pvt. Ltd is the state-of-the-art animation production facility of Toonz group. The 18,000 sq feet facility is nestled in Technopark, India's largest IT Park located in the South Indian state of Kerala, one of the must see destinations of a lifetime as described by National Geographic Traveller. From the creation of India's first 2D animated TV series & 2D feature film, to India's first 3D stereoscopic theatrical, the studio boasts of an envious pedigree that saw many successful coproduction partnerships with the likes of Walt Disney, Turner, Nickelodeon, Sony, Universal, BBC, Paramount, Marvel and Hallmark. Today, the studio has emerged as the leader in the Indian animation industry with a host of successful productions for the domestic market and one of the most admired studios in South East Asia. The studio has been heralded by Animation Magazine as 'one of the top ten studios to watch'and also been chosen as one among India's top ten 'cool' companies to work for. For more information, please visit https://www.indiamart.com/toonz-animation/aboutus.html DISTRIBUTION P r o d u c t s & S e r v i c e s Co-Production Financing / Co-Financing Global Distribution OTHER SERVICES P r o d u c t s & S e r v i c e s 3D Animation 2D Animation Post Production Story Boarding Animatic OTHER SERVICES: P r o d u c t s & S e r v i c e s Film TV Production Visual Effects CGI1 Visual Effects CGI F a c t s h e e t Year of Establishment : 1999 Nature of Business : Service Provider CONTACT US Toonz Animation India Private Limited Contact Person: Ramesh Kannan 731-735 Nila, Technopark Campus Thiruvananthapuram - 695581, Kerala, India https://www.indiamart.com/toonz-animation/. -

Bollywood and Postmodernism Popular Indian Cinema in the 21St Century

Bollywood and Postmodernism Popular Indian Cinema in the 21st Century Neelam Sidhar Wright For my parents, Kiran and Sharda In memory of Rameshwar Dutt Sidhar © Neelam Sidhar Wright, 2015 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road 12 (2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ www.euppublishing.com Typeset in 11/13 Monotype Ehrhardt by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Stockport, Cheshire, and printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7486 9634 5 (hardback) ISBN 978 0 7486 9635 2 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 0356 6 (epub) The right of Neelam Sidhar Wright to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). Contents Acknowledgements vi List of Figures vii List of Abbreviations of Film Titles viii 1 Introduction: The Bollywood Eclipse 1 2 Anti-Bollywood: Traditional Modes of Studying Indian Cinema 21 3 Pedagogic Practices and Newer Approaches to Contemporary Bollywood Cinema 46 4 Postmodernism and India 63 5 Postmodern Bollywood 79 6 Indian Cinema: A History of Repetition 128 7 Contemporary Bollywood Remakes 148 8 Conclusion: A Bollywood Renaissance? 190 Bibliography 201 List of Additional Reading 213 Appendix: Popular Indian Film Remakes 215 Filmography 220 Index 225 Acknowledgements I am grateful to the following people for all their support, guidance, feedback and encouragement throughout the course of researching and writing this book: Richard Murphy, Thomas Austin, Andy Medhurst, Sue Thornham, Shohini Chaudhuri, Margaret Reynolds, Steve Jones, Sharif Mowlabocus, the D.Phil.