Peace Process in India's Northeast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Naga Issue

18.08.2020 Tuesday Talking tough: On the Naga issue Context: The National Socialist Council of Nagaland- Isak-Muivah (NSCN-IM) has for the first time released the details of the 2015 framework agreement. What is the origin of Naga Issue and the timeline of the events? The assertion of Naga Nationalism began during Colonial period and continued in Independent India. Below is the pictorial representation of the timeline. What are the key demands of the Naga groups? 1. Greater Nagalim (sovereign statehood) i.e redrawing of boundaries to bring all Naga-inhabited areas in the Northeast under one administrative umbrella. 2. It includes various parts of Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, Assam and Myanmar as well. 3. Naga Yezabo (Naga Constitution) 4. Naga national flag. What was the Ceasefire Agreement which was signed in 2015? Interlocutor R.N. Ravi signed the agreement on behalf of the Centre in presence of PM Modi. The other two signatories were leader of NSCN(IM) i.e. Isak Chishi Swu, who died in 2016 and Thuingaleng Muivah (86) who is leading the talks. The Government of India recognised the unique history, culture and position of the Nagas and their sentiments and aspirations. The NSCN(IM) also appreciated the Indian political system and governance. 1 18.08.2020 Tuesday Significance: It shows the governments strong intent to resolve the long standing issue and adoption of diplomatic peaceful approach by Naga Society to fulfil their aspirations. Objective: Both sides agreed that October 2019 for concluding an accord, which would settle all Naga issues. The details of the agreement have not been made public by the government citing security reasons. -

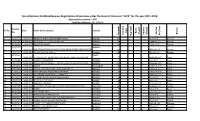

Fee Collections for Miscellaneous Registration of Societies Under The

Fee collections for Miscellaneous Registration of Societies under the Head of Accounts "1475" for the year 2017-2018 Applications recieved = 1837 Total fee collected = Rs. 2,20,541 Receipt Sl. No. Date Name of the Society District No. Copy Name Name Branch Change Change Challan Address Renewal Certified No./Date Duplicate 1 02410237 01-04-2017 NABAJYOTI RURAL DEVELOPMENT SOCIETY Barpeta 200 640/3-3-17 Barpeta 2 02410238 01-04-2017 MISSION TO THE HEARTS OF MILLION Barpeta 130 10894/28-3-17 Barpeta 3 02410239 01-04-2017 SEVEN STAR SOCIETY Barpeta 200 2935/9-3-17 Barpeta 02410240 Barpeta 4 01-04-2017 SIPNI SOCIO ECONOMIC AND CULTURAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANISATION 100 5856/15-2-17 Barpeta 5 02410241 01-04-2017 DESTINY WELFARE SOCIETY Barpeta 100 5857/15-2-17 Barpeta 08410259 Dhubri 6 01-04-2017 DHUBRI DISTRICT ENGINE BOAT (BAD BADHI) OWNER ASSOCIATION 75 14616/29-3-17 Dispur 7 15411288 03-04-2017 SOCIETY FOR CREATURE KAM(M) 52 40/3-4-17 Dispur 8 15411289 03-04-2017 MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE DAKHIN GUWAHATI JATIYA BIDYALAYA KAM(M) 125 15032/30-2-17 Dispur 9 24410084 03-04-2017 UNNATI SIVASAGAR 100 11384/15-3-17 Dispur 10 27410050 03-04-2017 AMGULI GAON MICRO WATERSHED COMMITTEE Udalguri 75 11836/16-2-17 Dispur 11 27410051 03-04-2017 MANPUR MICRO WATERSHED COMMITTEE Udalguri 75 11837/15-2-17 Dispur 12 27410052 03-04-2017 ULUBARI MICRO WATERSHED COMMITTEE Udalguri 75 11835/16-2-17 Dispur 13 15411291 04-04-2017 ST. CLARE CONVENT EDUCATIONAL SOCIETY KAM(M) 100 342/5-4-17 Dispur 14 16410228 04-04-2017 SERAPHINA SEVA SAMAJ KAM(R) 60 343/5-4-17 Dispur 15 16410234 -

Ajmal Foundation, Haji Mufassil Ali Complex, Gandhi Vidyapeeth Road

No.24-5/2017-N.M.(Assam) Government of India Ministry of Minority Affairs 11th Floor, Pt. Deendayal Antyodaya Bhawan, CGO Complex, Lodhi Road, New Delhi-3 Dated : 3v March, 2017 To The Pay and Accounts Officer Ministry of Minority Affairs, 11th Floor, Pt. Deendayal Antyodaya Bhawan, CGO Complex, Lodhi Road, New Delhi-110 003 Subject: Sanction of Project under Nai Manzil Scheme in the State of Assam to be implemented by Ajmal Foundation, Haji Mufassil Ali Complex, Gandhi Vidyapeeth Road, Hojai, Assam-782435 - Release of 1st installment (30%) of training cost for additional 120 trainees during 2016-17 Sir, In continuation of this Ministry's Sanction Order of even number dated 24.03.2017, I am directed to convey the approval of the President of India to sanction additional 120 Nos. of trainees under the Nai Manzil Project to Ajmal Foundation, Haji Mufassil All Complex, Gandhi Vidyapeeth Road, Hojai, Assam -782435 for the Assam State. The total number of trainees has been enhanced to 970 Nos. from 850 Nos. with this additional allocation. Consequently, the cost of the Project has also been enhanced to Rs. 5,48,05,000/- from Rs. 4,80,25,000/-. This cost ceiling is subject to common norms of Ministry of Skill Development & Entrepreneurship for skill component applicable from time to time. 2. I am also directed to convey the sanction of the President of India for release of Rs. 20,34,000/- ( Rupees twenty lakh and thirty four thousand only) (making total release to Rs. 1,64,41,500/-) for 970 trainees as 1st installment (30%) of Grants-in-aid to 111 Ajmal Foundation, Haji Mufassil Ali Complex, Gandhi Vidyapeeth Road, Hojai, Assam -782435 during 2016-17. -

Notice Regarding the Post of Para Legal Volounteer Under District

OFFICE OF THE DISTRICT LEGAL SERVICES AUTHORITY :: HOJAI;| SA KARDEV NAGAR (ASSAM) ]UDICIAI Cq'RT CAMRJS, SCNIGRDEV IIIAGAR, HOJAI (ASSAM), wN-74242 PHONE : 9707208575 E-MAIL ID : dlsahoiai@qmail,com I{OTICE Applications are invited from the local residents jn standard form along with two number of passport size photographs, for selection of around 70 numbers of pLV,s who are willing to serve as Para Legal Volunteer at Hoiai district under District Legal Services Authority, Hojai, Sankardev Nagar. The applicants should have the following qualifications to apply for the selection of Para Legal Volunteers- 1. He/ She must be a citizen of India and should be from any one of the follor\ring groups - ' Teachers (including retired teacheE) ' Retired Government servants and senior Gtizens. ' Master of Social Work Students and Teachers. ' Anganwadi Worlcrs. ' Doctors/ Ph)6icians. ' Students & Law Students (till they enroll as lawyers) ' Members of non- political, service oriented N@s and Clubs. ' Members of Women Neighborhood Groups, Maithri Sanghams and other Self Help Groups including Marginalized/ Vulnenble groups. 2. The applicants should pass minimum matriculatjon with a capacity for over all comprehension and should have mind set to assist the needy in society coupled with compassion, emEtthy and corrcern fior the uplifonent of marginalized and weaker sections of the society. They must have the unflindting commitment towards the cause which should be translated into the work they undertake. 3. Preferably the PLVS shall be selected, who do not look up to the income they derive from their services as PLVS, but they should have a mind set to assist the needy in the society. -

Greater Bangladesh

Annexure 3 Plan to Create Greater Bangla Desh including Assam in it Greater Bangladesh From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Greater Bangladesh (translated variously as Bengali : , Brihat Bangladesh ;[1] Bengali : Brihad Bangladesh ;[2] Bengali : , Maha Bangladesh ;[3] and Bengali : , Bishal Bangla [4] ) is a political theory circulated by a number of Indian politicians and writers that People's Republic of Bangladesh is trying for the territorial expansion to include the Indian states of West Bengal , Assam and others in northeastern India. [5] The theory is principally based on fact that a large number of Bangladeshi illegal immigrants reside in Indian territory. [6] Contents [hide ] 1 History o 1.1 United Bengal o 1.2 Militant organizations 2 Illegal immigration o 2.1 Lebensraum theory o 2.2 Nellie massacre o 2.3 The Sinha Report 3 References [edit ]History The ethno-linguistic region of Bengal encompasses the territory of Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal , as well as parts of Assam and Tripura . During the rule of the Hindu Sena dynasty in Bengal the notion of a Greater Bangladesh first emerged with the idea of uniting Bengali-speaking people in the areas now known as Orissa , Bihar and Indian North East (Assam, Tripura, and Meghalaya ) along with the Bengal .[7] These areas formed the Bengal Presidency , a province of British India formed in 1765, though Assam including Meghalaya and Sylhet District was severed from the Presidency in 1874, which became the Province of Assam together with Lushai Hills in 1912. This province was partitioned in 1947 into Hindu -majority West Bengal and Muslim - majority East Bengal (now Bangladesh) to facilitate the creation of the separate Muslim state of Pakistan , of which East Bengal became a province. -

Home-Makers Without the Men: Women-Headed Households in Violence-Wracked Assam

Home-Makers without the Men: Women-Headed Households in Violence-Wracked Assam Wasbir Hussain Home-Makers without the Men: Women-Headed Households in Violence-Wracked Assam Copyright© WISCOMP Foundation for Universal Responsibility Of His Holiness The Dalai Lama, New Delhi, India, 2006. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Published by WISCOMP Foundation for Universal Responsibility Of His Holiness The Dalai Lama Core 4A, UGF, India Habitat Centre Lodhi Road, New Delhi 110 003, India This initiative was made possible by a grant from the Ford Foundation. The views expressed here are those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect those of WISCOMP or the Foundation for Universal Responsibility of HH The Dalai Lama, nor are they endorsed by them. 2 Contents Preface………….....……….........………......................…….. 5 Acknowledgements………….....………………......................…….. 7 Conflict Dynamics in Assam: An Introduction ................................. 9 Home-Makers without the Men ....................................................... 14 Survivors of terror: Pariahs in society? ...................................... 19 How Lakshi Hembrom lost her power to think ......................... 23 Life’s cruel jokes on Kamrun Nissa ........................................... 27 Family ties cost Bharati Dear .................................................... -

Afspa and Insurgency in Nagaland

© 2019 JETIR April 2019, Volume 6, Issue 4 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) AFSPA AND INSURGENCY IN NAGALAND B ZUBENTHUNG EZUNG DR. TARIQ AHMED Department Of History, Department Of History Lovely Professional University, Lovely Professional University Phagwara -Punjab Phagwara- Punjab. ABSTRACT This research is made to understand how the Naga National Movement started, to examine the peace initiatives between the Government of India and the Naga leaders and also to analyze how affective the Naga National Movement has been. Here in this research we also try to understand the impacts of the Naga National Movement on the society and on the Naga people. Key Words: AFSPA, Insurgency, Nagaland, Naga Movements, NNC, FGN, NSCN-IM, NSCN-K INTRODUCTION Nagaland is a small state in the North eastern part of India. The Nagas lived in the North East hilly region of India and Myanmar. During the olden days, each Naga village was an independent republic so eventually the Nagas wanted to be free from all outside domination. Every Naga villages was independent and each with their own chiefs who acted as the leader, no other tribe had an interest in ruling over different or any other tribe or village. During an external aggression from foreign invaders all the Naga Chiefs collaborated and fought against the invaders. Nagas have been fighting to British and to the India & Burma for occupying their homeland illegally. The Naga nationalism first emerged in when thousands of Nagas participated in the British War efforts and saw action as members of the British Labor Force in France. However, having been exposed to the outside world and inspired by the material advancement, exposure to other cultures, and the reshaping of the political world by major movements. -

Chaiduar College

G.J.B.A.H.S.,Vol.2(3):141-145 (July – September, 2013) ISSN: 2319 – 5584 AQUATIC MACROPHYTES OF THE WETLANDS OF HOJAI SUB DIVISION, NAGAON DISTRICT OF ASSAM, INDIA Monjit Saikia Associate Professor, Department of Botany, Hojai College, Hojai, Nagaon-782435 (Assam) Abstract Hojai sub division is situated in the southern part of Nagaon district of Assam, India and global position in between the latitude 260:01/:05//N to 260:03/:00// N and 920:45/:40//E to 920:47/:05//E longitude. The study has been carried out for two years i.e from 2009 to 2010. Hojai contains 8 (oxbow type) beels covering total area of 345 hectare and Nabhanga beel was found to be with its highest depth (3.2 m). Altogether 62 macrophyte species of 51 genera under 30 families have been recorded, out of which 4 families are of Pteridophytes. 31 species were annual and 31species were perennial. Cyperaceae with its 5 genera and 9 species, Poaceae with its 7 genera and 7 species and Hydrocharitaceae with 6 genera and 7 species were found to be the dominant families in the study sites. Cyperus was the dominant genera with its 4 species. There were 6 exotic aquatic plants species recorded. The aquatic macrophyte species, growing along the marshy edges of the wetlands formed the dominant ecological category (Emergent anchored 35.48%) and widely distributed throughout the wetlands. These aquatic plants are used as vegetable, herbal medicine, fodder by the rural inhabitants of Hojai. Key words: Wetland, Beel, Hojai, Aquatic macrophyte. Introduction "Wetlands" is the collective term for marshes, swamps, bogs, and similar areas and are the source of many valuable aquatic flora and fauna including migratory birds and endangered species (Cowardin et al 1979). -

E4182 V1: Draft Final Report Vol. I

Public Disclosure Authorized Consultancy Services for Undertaking Environmental Assessment for the Rural Water Supply & Sanitation Project in Assam Public Disclosure Authorized March 2013 DRAFT FINAL REPORT VOLUME I Public Disclosure Authorized Submitted To: Chief Engineer (PHE), Assam. World Bank Project, Hengrabari,Guwahati-781036 Submitted By: IPE Global Pvt. Ltd. Public Disclosure Authorized (Formerly Infrastructure Professionals Enterprise (P) Ltd.) Address: IPE Towers, B-84, Defence Colony, Bhisham Pitamah Marg, New Delhi – 110024, India Tel: +91-11-40755920, 40755923; Fax: +91-11-24339534 Consultancy Services for Undertaking Environmental Assessment for the Rural Water Supply & Sanitation Project in Assam Draft Final Report Table of Contents Abbreviations and Acronyms ...............................................................................................................9 Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 11 1. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 21 1.1 Background ....................................................................................................................... 21 1.2 Present World Bank Assisted Rural Water Supply and Sanitation Project............................... 23 1.2.1 Components............................................................................................................... 23 -

National Socialist Council of Nagaland)

International Journal of Applied Social Science A CASE STUDY Volume 5 (3&4), March & April (2018) : 292-298 ISSN : 2394-1405 Received : 26.02.2018; Revised : 17.03.2018; Accepted : 24.03.2018 Extremism in Nagaland: A case study of NSCN (National Socialist Council of Nagaland) LIONG M. PHOM Department of Political Science, Lovely Professional University, Jalandhar (Punjab) India ABSTRACT National Socialist Council of Nagaland is an insurgent groups working mostly in Northeast India. The important purpose and goal of NSCN was to achieve sovereign Naga State. This research paper focuses on understanding clearly about the NSCN (Nationalist Socialist Council of Nagaland). The paper is to analyse the most important aim and working philosophy of NSCN on achieving sovereign Naga state. It shows the importance of NSCN sharing same interest with the Naga people as to which there will be a strong sense of brotherhood among them. The NSCN do not have full support of the people of Nagaland regarding the working activities in the State of Nagaland. They do not share the same interest in each and every decision. Opinions differ sometimes. The opinion of the Naga people is very important to support the working of NSCN. This study includes the impact of NSCN on the issues of violence in Nagaland and the working and functions of NSCN to set up Sovereign, Naga State. Key Words : National Socialist Council of Nagaland (NSCN), Sovereign, Violence, Extortion, Unity INTRODUCTION Nagaland is known as a beautiful hilly state which is one of the North East States of India. Nagaland is known for its dynamic tradition and cultural heritage which attract people from different parts of the world. -

Assam State Disaster Management Plan

ASSAM STATE DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN ASSAM STATE DISASTER MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY GOVERNMENT OF ASSAM CONTENTS Glossary of Key Terms ................................................................................................... v Abbreviations................................................................................................................vii PART – I DISASTER MANAGEMENT IN ASSAM .....................................................1 SECTION 1: THE ASSAM STATE DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN..................... 1 1.1.1 Authority to Plan.........................................................................................1 1.1.2 Aim and Purpose of the Plan.......................................................................1 1.1.3 Scope of the State Disaster Management Plan.............................................1 SECTION 2: PROFILE OF THE STATE ....................................................................... 2 1.2.1 Administrative Divisions ............................................................................2 1.2.2 Demography ...............................................................................................3 1.2.3 Key departments in the State.......................................................................3 1.2.4 Economy ....................................................................................................4 1.2.5 Geography..................................................................................................5 1.2.6 Physiographic Divisions..............................................................................7 -

Naga Peace Talks Being Delayed?

22 September, 2021 Four years after the government inked the Naga peace accord in 2015, the Centre has now said that the process had almost concluded, despite the fact that the talks had hit a roadblock in its final stages. Why is the Naga Peace talks being delayed? It is mainly because of unrealistic demands. NSCN I-M has issued statements in the past claiming that it wanted a separate Constitution, flag and integration of all contiguous Naga-inhabited areas under Nagalim (Greater Nagaland). Government of India’s stand: A mutually agreed draft comprehensive settlement, including all the substantive issues and competencies, is ready for inking the final agreement. Respecting the Naga people’s wishes, the Government of India is determined to conclude the peace process without delay. How old is the Naga political issue? Pre- independence: 1. The British annexed Assam in 1826, and in 1881, the Naga Hills too became part of British India. The first sign of Naga resistance was seen in the formation of the Naga Club in 1918, which told the Simon Commission in 1929 “to leave us alone to determine for ourselves as in ancient times”. 2. In 1946 came the Naga National Council (NNC), which declared Nagaland an independent state on August 14, 1947. 3. The NNC resolved to establish a “sovereign Naga state” and conducted a “referendum” in 1951, in which “99 per cent” supported an “independent” Nagaland. What are the Naga peace talks? The talks seek to settle disputes that date back to colonial rule. The Nagas are not a single tribe, but an ethnic community that comprises several tribes who live in the state of Nagaland and its neighbourhood One key demand of Naga groups has been a Greater Nagalim that would cover not only the state of Nagaland but parts of neighbouring states, and even of Myanmar.