Case Study of Kampala-Entebbe Express Highway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stichting Porticus

CATHOLIC SCHOLARSHIP PROGRAMME FOR UGANDA C/o University of Kisubi P.O. Box 182 Entebbe, Uganda Photograph Tel. +256 777 606093 Email: [email protected] APPLICATION FORM Please be advised that the eligibility requirements for the Scholarship Programme have changed in 2019; please refer to the Catholic Scholarship Programme Eligibility Requirements, 2019 which are attached as Annex A. Each applicant must write a Personal Statement, please follow the template attached as Annex B. Each applicant must have two (2) Letters of Recommendation, including one from your superior. Please follow the template attached as Annex C. Finally, this application should be submitted together with the list of documents on page 4. PERSONAL DETAILS Surname:…………………………………………………… First and Middle names: …….……………………….……………………. Other names ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...…………..………..……… Date of birth: ………………………………...... Place of birth: …………………………………..…………….................... Nationality: ………………………………………. Identity card no/ Passport no:…….…..………………………...……… Religious ☐ Lay ☐ Mobile phone numbers: ………………….…………….…................. E-mail: ……………………………………………………………………………………………. Gender: ……….……………………..……………. Permanent address: …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..……...……….. Name of Nominating Institution (the Congregation or organization that is nominating the student for a scholarship): ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….……………………….……. Local Congregation:………………………………………. Pontifical Institute……………………………………………..………………. Superior/Next -

Parenting Styles and Students' Academic Performance

PARENTING STYLES AND STUDENTS’ ACADEMIC PERFORMANCE OF SENIOR TWO AND SENIOR FIVE STUDENTS IN MASULIITA TOWN COUNCIL: A CASE OF SELECTED SECONDARY SCHOOLS BY KYOBE CHARLES A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF EDUCATION HUMANITIES AND SCIENCES OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF A MASTER’S DEGREE EDUCATION MANAGEMENT AND PLANNING OF NKUMBA UNIVERSITY OCTOBER, 2018 1 DECLARATION I, Kyobe Charles, hereby declare that this research report is my original work and to the best of my knowledge, it has never been submitted for any academic award in this or any other institution of higher learning. i APPROVAL This dissertation titled “PARENTING STYLES AND STUDENTS’ ACADEMIC PERFORMANCE OF SENIOR TWO AND SENIOR FIVE STUDENTS IN MASULIITA TOWN COUNCIL: A CASE OF SELECTED SECONDARY SCHOOLS” has been prepared by Kyobe Charles under my supervision and it is now ready for submission. ii DEDICATION I dedicate this dissertation to my loving and caring family for the sacrifices made in supporting my studies. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I wish to thank the Almighty God who has brought me this far in my life, and has kept me safe to this stage. I pray that he can give me more countless years so that I can serve him relentless. I wish to thank my Superior General the Archbishop of Kampala Archdiocese Dr. Cyprian Kizito Lwanga, the Vicar General Monsignor Charles Kasibante and my Rector Reverend Father Ceasar Matovu, and my spiritual director Reverend Father Emmanuel Kasajja for all the support you have accorded throughout my academic endavours to this stage. To my dear parents; Mr. -

Uganda Gazette Authority Vol

GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY 703 (j ^76/ (7 S' ZMCflyZ, The THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA Registered at the -ww- -^r-OT AVAILABLE FOR LC-.?-w| A A Published General Post Officefor transmission within by East Africa as a Newspaper Uganda Gazette Authority Vol. CIV No. 15 1st March, 2011 Price: Shs. 1500 CONTENTS Page General Notice No. 145 of 2011. The Electoral Commission Act—Notices ... 703-704 THE ELECTORAL COMMISSION ACT Advertisements.................................................... 704 SUPPLEMENT CAP. 140 Statutory Instrument SECTION 12 (1) (a) No. 8—The Kampala Capital City (Commencement) Instrument, 2011. NOTICE APPOINTMENT OF POLLING DAY FOR PURPOSES OF General Notice No. 143 of 2011. ELECTING REPRESENTATIVES OF THE UGANDA THE ELECTORAL COMMISSION ACT, CAP. 140 PEOPLES DEFENCE FORCES (UPDF) TO PARLIAMENT SECTION 30 (1) NOTICE Notice is hereby given by the Electoral Commission in APPOINTMENT OF RETURNING OFFICER FOR accordance with Section 12 (1) (a) of the Electoral Commission MASAKA ELECTORAL DISTRICT Act, Cap. 140, that the 7th March, 2011 is hereby appointed and published polling day for purposes of electing the Uganda Notice is hereby given by the Electoral Commission in accordance with Section 30 (1) of the Electoral Commission Act, Peoples' Defence Forces (UPDF) to Parliament. Cap. 140, that Mr. Musinguzi Tolbert, Ag. District Registrar, Issued at Kampala this 1st day of March, 2011. Masaka Electoral District, is hereby appointed Returning Officer for Masaka Electoral Commission with immediate effect ENG. DR. BADRU M. KIGGUNDU, Issued at Kampala this 1st day of March, 2011. Chairperson, Electoral Commission. ENG. DR. BADRU M. KIGGUNDU, Chairperson, Electoral Commission. General Notice No. -

Best Schools in Biology (UACE 2019)

UACE RESULTS NEW VISION, Monday, March 2, 2020 57 Best Schools in Literature (UACE 2019) NO OF T/TAL AV NO OF T/TAL NO OF T/TAL NO OF T/TAL T/TAL NO SCHOOL SCORE StD’S STD’S AV AV AV AV NO OF NO SCHOOL SCORE StD’S STD’S NO SCHOOL SCORE StD’S STD’S NO SCHOOL SCORE StD’S STD’S NO SCHOOL SCORE StD’S STD’S 1 St.Henry's Col.,Kitovu 5.54 13 108 41 Kitagata HS 4.25 12 39 81 St. Kalemba,Villa Maria 4.00 2 31 121 Kennedy SS,Kisubi 3.86 7 97 161 St. Peter's SS, Naalya 3.62 52 325 2 King's Col.,Budo 5.52 23 200 42 Kangole Girls' School 4.25 4 24 82 The Ac. St.Lawrence Budo 4.00 3 28 122 Nyabubare SS 3.86 14 92 162 Katikamu SS 3.60 10 144 3 Mengo SS 5.33 3 492 43 Kisubi Seminary 4.22 9 35 83 Sir Apollo Kaggwa, Mukono 4.00 1 28 123 Jeressar HS,Soroti 3.83 30 227 163 Kawanda SS 3.60 5 131 4 St. Joseph’s SS,Naggalama 5.18 11 87 44 Our Lady Of Africa,Mukono 4.22 23 247 84 Kitabi Seminary 4.00 2 28 124 Bp. Cyprian Kyabakadde 3.83 6 104 164 St.Lucia Hill, Namagoma 3.60 5 107 5 Mt.St. Mary’s,Namagunga 5.15 20 114 45 Sac’d Heart SS,Mushanga 4.21 14 57 85 City SS, Kayunga Wakiso 4.00 2 28 125 P.M.M Girls' School,Jinja 3.83 12 58 165 Wanyange Girls School 3.60 25 56 6 Maryhill HS 5.10 20 124 46 Kalinabiri SS 4.20 5 74 86 Bushenyi Progressive HS 4.00 6 28 126 Sheema Girls' School 3.83 6 45 166 Bp. -

Vote:781 Kira Municipal Council Quarter1

Local Government Quarterly Performance Report FY 2017/18 Vote:781 Kira Municipal Council Quarter1 Terms and Conditions I hereby submit Quarter 1 performance progress report. This is in accordance with Paragraph 8 of the letter appointing me as an Accounting Officer for Vote:781 Kira Municipal Council for FY 2017/18. I confirm that the information provided in this report represents the actual performance achieved by the Local Government for the period under review. Name and Signature: Accounting Officer, Kira Municipal Council Date: 27/08/2019 cc. The LCV Chairperson (District) / The Mayor (Municipality) 1 Local Government Quarterly Performance Report FY 2017/18 Vote:781 Kira Municipal Council Quarter1 Summary: Overview of Revenues and Expenditures Overall Revenue Performance Ushs Thousands Approved Budget Cumulative Receipts % of Budget Received Locally Raised Revenues 7,511,400 1,237,037 16% Discretionary Government Transfers 2,214,269 570,758 26% Conditional Government Transfers 4,546,144 1,390,439 31% Other Government Transfers 0 308,889 0% Donor Funding 0 0 0% Total Revenues shares 14,271,813 3,507,123 25% Overall Expenditure Performance by Workplan Ushs Thousands Approved Cumulative Cumulative % Budget % Budget % Releases Budget Releases Expenditure Released Spent Spent Planning 298,531 40,580 12,950 14% 4% 32% Internal Audit 110,435 15,608 10,074 14% 9% 65% Administration 1,423,810 356,949 150,213 25% 11% 42% Finance 1,737,355 147,433 58,738 8% 3% 40% Statutory Bodies 1,105,035 225,198 222,244 20% 20% 99% Production and Marketing -

S5 Cut Off May Raise

SATURDAY VISION 10 February 1, 2020 UCE Vision ranking explained Senior Five cut-off points (2019) SCHOOL Boys SCHOOL Boys BY VISION REPORTER their students in division one. Girls Fees (Sh) Girls Fees (Sh) The other, but with a low number of St. Mary’s SS Kitende 10 12 1,200,000 Kinyasano Girls HS 49 520,000 The Saturday Vision ranking considered candidates and removed from the ranking Uganda Martyrs’ SS Namugongo 10 12 1,130,000 St. Bridget Girls High Sch 50 620,000 the average aggregate score to rank was Lubiri Secondary School, Annex. It Kings’ Coll. Budo 10 12 1,200,000 St Mary’s Girls SS Madera Soroti 50 595,200 the schools. Saturday Vision also also had 100% of its candidates passing Light Academy SS 12 1,200,000 Soroti SS 41 53 UPOLET eliminated all schools which had in division one. Namilyango Coll. 14 1,160,000 Nsambya SS 42 42 750,000 the number of candidates below 20 There are other 20 schools, in the entire London Coll. of St. Lawrence 14 16 1,300,000 Gulu Central HS 42 51 724,000 students in the national ranking. nation, which got 90% of their students in The Academy of St. Lawrence 14 16 650,000 Vurra Secondary School 42 52 275,000 A total of about 190 schools were division one. removed from the ranking on this Naalya Sec Sch, Namugongo 15 15 1,000,000 Lango Coll. 42 500,000 basis. nTRADITIONAL, PRIVATE Seeta High (Green Campus) 15 15 1,200,000 Mpanga SS-Kabarole 43 51 UPOLET This is because there were schools with SCHOOLS TOP DISTRICT RANKING Seeta High (Mbalala) 15 15 1,200,000 Gulu SS 43 53 221,000 smaller sizes, as small as five candidates, Traditional schools and usual private top Seeta High (Mukono) 15 15 1,200,000 Lango Coll., S.S 43 like Namusiisi High School in Kaliro. -

THE UGANDA GAZETTE [2 3 Rd M a R C H

The THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA iTHE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA Registered at the Published General Post Office for transmission within by East Africa as a Newspaper Uganda Gazette Authority Vol. CXI No. 15 23rd March, 2018 Price: Shs. 5,000 CONTENTS Pa g e SCHEDULE The Marriage Act—Notice ................ ... 367 The Electoral Commission Act—Notice............... 367 Name o f Political Votes S/N The Advocates Act—Notices... ... ... 367-368 Candidates Party/Organisation Obtained The Mining Act—Notice ................ ... 368 The Companies Act—Notices................ ... 368-369 1. Abuze Monica Independent 18 The Control of Private Security Organisations Igeme Nathan National Resistance 2. 5,043 Regulations—Notice ... ... ... 369 Nabeta Samson Movement The Pharmacy and Drugs Act—Notice ... 369-377 Isabirye Hatimu 3. Independent 7 The Industrial Property Act—Registration of Mugendi Industrial Designs ... ... ... 377 Mayemba Faisal The Trademarks Act—Registration of Applications 378-386 4. Independent 117 Masaba Advertisements ... ... ... ... 387-398 Mugaya Paul People’s Progressive 5. 48 SUPPLEMENT Geraldson Party Statutory Instrument / Forum for 6. Mwiru Paul 6,654 No. 9—The Insurance Act, 2017 (Commencement) Democratic Change Instrument, 2018. Nyanzi Richard 7. Independent 47 Henry General Notice No. 226 of 2018. 8. Wakabi Francis Independent 24 THE MARRIAGE ACT Issued at Kampala, this 21st day of March, 2018. [Cap. 251 Revised Edition, 2000] NOTICE. JUSTICE BYABAKAMA MUGENYI SIMON, Chairperson, Electoral Commission. PLACE FOR CELEBRATION OF MARRIAGE [Under Section 5 o f the Act] General Notice No. 228 of 2018. In e x e r c is e of the powers conferred upon me by Section 5 of the Marriage Act, I hereby licence the place for Public THE ADVOCATES ACT, CAP. -

Republic of Uganda

REPUBLIC OF UGANDA VALUE FOR MONEY AUDIT REPORT ON SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT IN KAMPALA MARCH 2010 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS REPUBLIC OF UGANDA .......................................................................................................... 1 VALUE FOR MONEY AUDIT REPORT ..................................................................................... 1 ON SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT IN KAMPALA .................................................................... 1 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ...................................................................................................... 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER 1 ......................................................................................................................... 10 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 10 1.0 BACKGROUND .............................................................................................10 1.1 MOTIVATION ...............................................................................................12 1.2 MANDATE ....................................................................................................13 1.3 VISION ........................................................................................................13 1.4 MISSION ................................................................................................................. -

Kampala Cholera Situation Report

Kampala Cholera Situation Report Date: Monday 4th February, 2019 1. Summary Statistics No Summary of cases Total Number Total Cholera suspects- Cummulative since start of 54 #1 outbreak on 2nd January 2019 1 New case(s) suspected 04 2 New cases(s) confirmed 54 Cummulative confirmed cases 22 New Deaths 01 #2 3 New deaths in Suspected 01 4 New deaths in Confirmed 00 5 Cumulative cases (Suspected & confirmed cases) 54 6 Cumulative deaths (Supected & confirmed cases) in Health Facilities 00 Community 03 7 Total number of cases on admission 00 8 Cummulative cases discharged 39 9 Cummulative Runaways from isolation (CTC) 07 #3 10 Number of contacts listed 93 11 Total contacts that completed 9 day follow-up 90 12 Contacts under follow-up 03 13 Total number of contacts followed up today 03 14 Current admissions of Health Care Workers 00 13 Cummulative cases of Health Care Workers 00 14 Cummulative deaths of Health Care Workers 00 15 Specimens collected and sent to CPHL today 04 16 Cumulative specimens collected 45 17 Cummulative cases with lab. confirmation (acute) 00 Cummulative cases with lab. confirmation (convalescent) 22 18 Date of admission of last confirmed case 01/02/2019 19 Date of discharge of last confirmed case 02/02/2019 20 Confirmed cases that have died 1 (Died from the community) #1 The identified areas are Kamwokya Central Division, Mutudwe Rubaga, Kitintale Zone 10 Nakawa, Naguru - Kasende Nakawa, Kasanga Makindye, Kalambi Bulaga Wakiso, Banda Zone B3, Luzira Kamwanyi, Ndeba-Kironde, Katagwe Kamila Subconty Luwero District, -

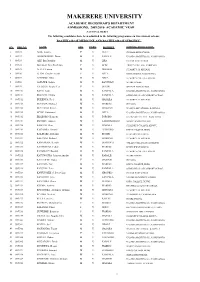

Makerere University

MAKERERE UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC REGISTRAR'S DEPARTMENT ADMISSIONS, 2009/2010 ACADEMIC YEAR NATIONAL MERIT The following candidates have been admitted to the following programme on Government scheme: BACHELOR OF MEDICINE AND BACHELOR OF SURGERY S/N REG NO NAME SEX C'TRY DISTRICT SCHOOL/ INSTITUTION 1 09/U/1 AGIK Sandra F U GULU GAYAZA HIGH SCHOOL 2 09/U/2 AHIMIBISIBWE Davis M U KABALE UGANDA MARTYRS S.S., NAMUGONGO 3 09/U/3 AKII Bua Douglas M U LIRA HILTON HIGH SCHOOL 4 09/U/4 AKULLO Pamella Winnie F U APAC TRINITY COLLEGE, NABBINGO 5 09/U/5 ALELE Franco M U DOKOLO ST MARY'S SS KITENDE 6 09/U/6 ALENI Caroline Acidri F U ARUA MT.ST.MARY'S, NAMAGUNGA 7 09/U/7 AMANDU Allan M U ARUA ST MARY'S COLLEGE, KISUBI 8 09/U/8 ASIIMWE Joshua M U KANUNGU NTARE SCHOOL 9 09/U/9 AYAZIKA Kirabo Tess F U BUGIRI GAYAZA HIGH SCHOOL 10 09/U/10 BAYO Louis M U KAMPALA UGANDA MARTYRS S.S., NAMUGONGO 11 09/U/11 BUKAMA Martin M U KAMPALA OLD KAMPALA SECONDARY SCHOOL 12 09/U/12 BUKENYA Fred M U MASAKA ST MARY'S SS KITENDE 13 09/U/13 BUYINZA Michael M U WAKISO DIPLOMA 14 09/U/14 BUYUNGO Steven M U MUKONO NAALYA SEC. SCHOOL ,KAMPALA 15 09/U/15 ECONI Emmanuel M U ARUA UGANDA MARTYRS S.S., NAMUGONGO 16 09/U/16 EKAKORO Kenneth M U TORORO KATIKAMU SEC. SCH., WOBULENZI 17 09/U/17 EMYEDU Andrew M U KABERAMAIDO NAMILYANGO COLLEGE 18 09/U/18 KABUGO Deus M U MASAKA ST HENRY'S COLLEGE, KITOVU 19 09/U/19 KAGAMBA Samuel M U LUWEERO KING'S COLLEGE, BUDO 20 09/U/20 KALINAKI Abubakar M U BUGIRI KAWEMPE MUSLIM SS 21 09/U/21 KALUNGI Richard M U MUKONO ST MARY'S SS KITENDE 22 09/U/22 KANANURA Keneth M U BUSHENYI VALLEY COLLEGE SS, BUSHENYI 23 09/U/23 KATEREGGA Fahad M U WAKISO KAWEMPE MUSLIM SS 24 09/U/24 KATSIGAZI Ronald M U KAMPALA ST MARY'S COLLEGE, KISUBI 25 09/U/25 KATUNGUKA Johnson Sunday M U KABALE NTARE SCHOOL 26 09/U/26 KATUSIIME Hawa F U MASINDI DIPLOMA 27 09/U/27 KAVUMA Paul M U WAKISO KING'S COLLEGE, BUDO 28 09/U/28 KAVUMA Peter M U KAMPALA OLD KAMPALA SECONDARY SCHOOL 29 09/U/29 KAWUNGEZI S. -

Approved Bodaboda Stages

Approved Bodaboda Stages SN Division Parish Stage ID X-Coordinate Y-Coordinate 1 CENTRAL DIVISION BUKESA 1001 32.563999 0.317146 2 CENTRAL DIVISION BUKESA 1002 32.564999 0.317240 3 CENTRAL DIVISION BUKESA 1003 32.566799 0.319574 4 CENTRAL DIVISION BUKESA 1004 32.563301 0.320431 5 CENTRAL DIVISION BUKESA 1005 32.562698 0.321824 6 CENTRAL DIVISION BUKESA 1006 32.561100 0.324322 7 CENTRAL DIVISION INDUSTRIAL AREA 1007 32.610802 0.312010 8 CENTRAL DIVISION INDUSTRIAL AREA 1008 32.599201 0.314553 9 CENTRAL DIVISION KAGUGUBE 1009 32.565701 0.325353 10 CENTRAL DIVISION KAGUGUBE 1010 32.569099 0.325794 11 CENTRAL DIVISION KAGUGUBE 1011 32.567001 0.327003 12 CENTRAL DIVISION KAGUGUBE 1012 32.571301 0.327249 13 CENTRAL DIVISION KAMWOKYA II 1013 32.583698 0.342530 14 CENTRAL DIVISION KOLOLO I 1014 32.605900 0.326255 15 CENTRAL DIVISION KOLOLO I 1015 32.605400 0.326868 16 CENTRAL DIVISION MENGO 1016 32.567101 0.305112 17 CENTRAL DIVISION MENGO 1017 32.563702 0.306650 18 CENTRAL DIVISION MENGO 1018 32.565899 0.307312 19 CENTRAL DIVISION MENGO 1019 32.567501 0.307867 20 CENTRAL DIVISION MENGO 1020 32.567600 0.307938 21 CENTRAL DIVISION MENGO 1021 32.569500 0.308241 22 CENTRAL DIVISION MENGO 1022 32.569199 0.309950 23 CENTRAL DIVISION MENGO 1023 32.564800 0.310082 24 CENTRAL DIVISION MENGO 1024 32.567600 0.311253 25 CENTRAL DIVISION MENGO 1025 32.566002 0.311941 26 CENTRAL DIVISION OLD KAMPALA 1026 32.567501 0.314132 27 CENTRAL DIVISION OLD KAMPALA 1027 32.565701 0.314559 28 CENTRAL DIVISION OLD KAMPALA 1028 32.566002 0.314855 29 CENTRAL DIVISION OLD -

THE UGANDA GAZETTE [13Th J Anuary

The THE RH Ptrat.ir OK I'<1 AND A T IE RKPt'BI.IC OF UGANDA Registered at the Published General Post Office for transmission within by East Africa as a Newspaper Uganda Gazette A uthority Vol. CX No. 2 13th January, 2017 Price: Shs. 5,000 CONTEXTS P a g e General Notice No. 12 of 2017. The Marriage Act—Notice ... ... ... 9 THE ADVOCATES ACT, CAP. 267. The Advocates Act—Notices ... ... ... 9 The Companies Act—Notices................. ... 9-10 NOTICE OF APPLICATION FOR A CERTIFICATE The Electricity Act— Notices ... ... ... 10-11 OF ELIGIBILITY. The Trademarks Act—Registration of Applications 11-18 Advertisements ... ... ... ... 18-27 I t is h e r e b y n o t if ie d that an application has been presented to the Law Council by Okiring Mark who is SUPPLEMENTS Statutory Instruments stated to be a holder of a Bachelor of Laws Degree from Uganda Christian University, Mukono, having been No. 1—The Trade (Licensing) (Grading of Business Areas) Instrument, 2017. awarded on the 4th day of July, 2014 and a Diploma in No. 2—The Trade (Licensing) (Amendment of Schedule) Legal Practice awarded by the Law Development Centre Instrument, 2017. on the 29th day of April, 2016, for the issuance of a B ill Certificate of Eligibility for entry of his name on the Roll of Advocates for Uganda. No. 1—The Anti - Terrorism (Amendment) Bill, 2017. Kampala, MARGARET APINY, 11th January, 2017. Secretary, Law Council. General N otice No. 10 of 2017. THE MARRIAGE ACT [Cap. 251 Revised Edition, 2000] General Notice No.