Adrian Lester OBE Interviewed by Stephanie Dale – Writer, Lecturer and MAC Board Member

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hamlet-Production-Guide.Pdf

ASOLO REP EDUCATION & OUTREACH PRODUCTION GUIDE 2016 Tour PRODUCTION GUIDE By WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE ASOLO REP Adapted and Directed by JUSTIN LUCERO EDUCATION & OUTREACH TOURING SEPTEMBER 27 - NOVEMBER 22 ASOLO REP LEADERSHIP TABLE OF CONTENTS Producing Artistic Director WHAT TO EXPECT.......................................................................................1 MICHAEL DONALD EDWARDS WHO CAN YOU TRUST?..........................................................................2 Managing Director LINDA DIGABRIELE PEOPLE AND PLOT................................................................................3 FSU/Asolo Conservatory Director, ADAPTIONS OF SHAKESPEARE....................................................................5 Associate Director of Asolo Rep GREG LEAMING FROM THE DIRECTOR.................................................................................6 SHAPING THIS TEXT...................................................................................7 THE TRAGEDY OF HAMLET CREATIVE TEAM FACT IN THE FICTION..................................................................................9 Director WHAT MAKES A GHOST?.........................................................................10 JUSTIN LUCERO UPCOMING OPPORTUNITIES......................................................................11 Costume Design BECKI STAFFORD Properties Design MARLÈNE WHITNEY WHAT TO EXPECT Sound Design MATTHEW PARKER You will see one of Shakespeare’s most famous tragedies shortened into a 45-minute Fight Choreography version -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

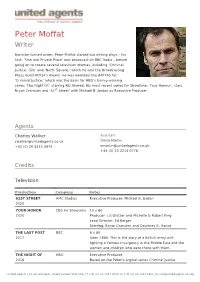

Peter Moffat Writer

Peter Moffat Writer Barrister turned writer, Peter Moffat started out writing plays – his first, ‘Fine and Private Place’ was broadcast on BBC Radio – before going on to create several television dramas, including ‘Criminal Justice, ‘Silk’ and ‘North Square,’ which he won the Broadcasting Press Guild Writer’s Award. He was awarded two BAFTAS for ‘Criminal Justice,’ which was the basis for HBO’s Emmy-winning series ‘The Night Of,’ starring Riz Ahmed. His most recent series for Showtime, ‘Your Honour,’ stars Bryan Cranston and ‘61st Street’ with Michael B. Jordan as Executive Producer. Agents Charles Walker Assistant [email protected] Olivia Martin +44 (0) 20 3214 0874 [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0778 Credits Television Production Company Notes 61ST STREET AMC Studios Executive Producer: Michael B. Jordan 2020 YOUR HONOR CBS for Showtime 10 x 60 2020 Producer: Liz Glotzer and Michelle & Robert King Lead Director: Ed Berger Starring: Bryan Cranston and Courtney B. Vance THE LAST POST BBC 6 x 60 2017 Aden 1965. This is the story of a British army unit fighting a Yemeni insurgency in the Middle East and the women and children who were there with them. THE NIGHT OF HBO Executive Producer 2016 Based on the Peter's orginal series Criminal Justice United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes UNDERCOVER BBC1 6 x60' with Sophie Okonedo and Adrian Lester, Denis 2015 Haysbert Director James Hawes, Exec Producer Peter Moffat THE VILLAGE series Company Pictures 6 x 60' with John Simm, Maxine Peake, Juliet Stevenson 1 / BBC1 Producer: Emma Burge; Director: Antonia Bird 2013 SILK 2 BBC1 6 x 60' With Maxine Peake, Rupert Penry Jones, Frances 2012 Barber, and Neil Stuke Producer: Richard Stokes; Directors: Alice Troughton, Jeremy Webb, Peter Hoar SILK BBC1 6 x 60' 2011 With Maxine Peake, Rupert Penry Jones, Natalie Dormer, Tom Hughes and Neil Stuke. -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

James Strong Director

James Strong Director Agents Michelle Archer Assistant Grace Baxter [email protected] 020 3214 0991 Credits Television Production Company Notes CRIME Buccaneer/Britbox Lead Director and Executive Producer. 2021 Episodes 1-3. Writer: Irvine Welsh, based on his novel by the same name. Producer: David Blair. Executive producers: Irvine Welsh, Dean Cavanagh, Dougray Scott andTony Wood. VIGIL World Productions / BBC One Lead Director and Executive Producer. 2019 - 2020 Episodes 1- 3. Starring Suranne Jones, Rose Leslie, Shaun Evans. Writer: Tom Edge. Executive Producer: Simon Heath. United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes LIAR 2 Two Brothers/ ITV Lead Director and Executive Producer. 2019 Episodes 1-3. Writers: Jack and Harry Williams Producer: James Dean Executive Producer: Chris Aird Starring: Joanne Froggatt COUNCIL OF DADS NBC/ Jerry Bruckheimer Pilot Director and Executive Producer. 2019 Television/ Universal TV Inspired by the best-selling memoir of Bruce Feiler. Series ordered by NBC. Writers: Tony Phelan, Joan Rater. Producers: James Oh, Bruce Feiler. Exec Producers: Jerry Bruckheimer, Jonathan Littman, KristieAnne Read, Tony Phelan, Joan Rater. VANITY FAIR Mammoth/Amazon/ITV Lead Director and Executive Producer. 2017 - 2018 Episodes 1,2,3,4,5&7 Starring Olivia Cooke, Simon Russell Beale, Martin Clunes, Frances de la Tour, Suranne Jones. Writer: Gwyneth Hughes. Producer: Julia Stannard. Exec Producers: Gwyneth Hughes, Damien Timmer, Tom Mullens. LIAR ITV/Two Brothers Pictures Lead Director and Executive Producer. 2016 - 2017 Episodes 1 to 3. Writers: Harry and Jack Williams. -

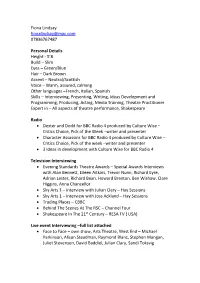

Fiona Lindsay [email protected] 07836767487

Fiona Lindsay [email protected] 07836767487 Personal Details Height - 5’8 Build – Slim Eyes – Green/Blue Hair – Dark Brown Accent – Neutral/Scottish Voice – Warm, assured, calming Other languages –French, Italian, Spanish Skills – Interviewing, Presenting, Writing, Ideas Development and Programming, Producing, Acting, Media Training, Theatre Practitioner Expert in – All aspects of theatre performance, Shakespeare Radio Dexter and Dodd for BBC Radio 4 produced by Culture Wise – Critics Choice, Pick of the Week –writer and presenter Character Assassins for BBC Radio 4 produced by Culture Wise – Critics Choice, Pick of the week –writer and presenter 3 Ideas in development with Culture Wise for BBC Radio 4 Television Interviewing Evening Standards Theatre Awards – Special Awards Interviews with Alan Bennett, Eileen Aitkins, Trevor Nunn, Richard Eyre, Adrian Lester, Richard Bean, Howard Brenton, Ben Wishaw, Clare Higgins, Anna Chancellor Sky Arts 1 – Interview with Julian Clary – Hay Sessions Sky Arts 1 – Interview with Joss Ackland – Hay Sessions Trading Places – CBBC Behind The Scenes At The RSC – Channel Four Shakespeare In The 21st Century – RESA TV ( USA) Live event Interviewing –full list attached Face to Face – own show, Arts Theatre, West End – Michael Parkinson, Alison Steadman, Raymond Blanc, Stephen Mangan, Juliet Stevenson, David Baddiel, Julian Clary, Sandi Toksvig Cheltenham Literature Festival – recent interviews include – Rupert Everett, Ken Dodd, Paul O’Grady, Patricia Hodge, Sandi Toksvig, Ben Fogle, Stephen -

ENGL August Intersession 2021 Course Description Packet

Undergraduate Course Description Packet August Intersession 2021 Updated: 3/16/21 ENGL 4933-002, Studies in Popular Culture and Popular Genres: Shakespeare in Film Instructor: D. Stephens Textbooks Required: Each student must have a subscription to Prime Video; if timed correctly, this may be obtained as a free one-month trial that covers the dates of the course. Information is here, under “See More Plans” (three lines below the orange “Try Prime” button): https://www.amazon.com/amazonprime?_encoding=UTF8&pd_rd_r=ce6f99f1-b9cb-4ff6-85fc-d8 0d65691ced&pd_rd_w=zi5Kz&pd_rd_wg=7XCJZ&qid=1601330401 Ed. Greenblatt, Stephen, The Norton Shakespeare eBook. This required text will appear on Blackboard as an e-book at the start of the semester. The price is being negotiated, but it will be around $35. Your student account will be charged approximately a week after the semester begins. If you already have a copy of the complete Norton Shakespeare, or of a recent edition of the Riverside or Pelican complete Shakespeare, we can arrange for you to opt out of having your student account charged Description: We will read four plays by Shakespeare and watch many film adaptations of these works—some at full length and many more as clips. Here is a sampling: we will analyze Asta Nielsen’s 1921 Hamlet starring herself, and we will compare modern Hamlets played by David Tennant, Patrick Stewart, Benedict Cumberbatch, Adrian Lester, and Andrew Scott. We will look at selections from Aki Kaurismaki’s Finnish Hamlet Goes Business and Kurosawa’s The Bad Sleep Well. We will view The Tempest in a science-fiction adaptation and in a stop-motion puppet production. -

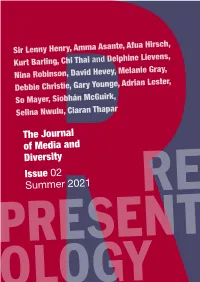

The Journal of Media and Diversity Issue 02 Summer 2021

Sir Lenny Henry, Amma Asante, Afua Hirsch, Kurt Barling, Chi Thai and Delphine Lievens, Nina Robinson, David Hevey, Melanie Gray, Debbie Christie, Gary Younge, Adrian Lester, So Mayer, Siobhán McGuirk, Selina Nwulu, Ciaran Thapar The Journal of Media and Diversity Issue 02 Summer 2021 1 REPRESENTOLOGY THE JOURNAL OF MEDIA AND DIVERSITY ISSUE 02 SUMMER 2021 REPRESENTOLOGY CONTENTS EDITORIAL The Journal of Media and Diversity 04 Developing Film Welcome to Issue Two of Representology - Sir Lenny Henry and Amma Asante The Journal of Media and Diversity. Since we Editorial Mission Statement interview. launched, many of you have shared 14 Finding My Voice encouraging words and ideas on how to help Welcome to Representology, a journal Afua Hirsch create a media more reflective of modern dedicated to research and best-practice 18 Putting the Black into Britain Britain. perspectives on how to make the media more Professor Kurt Barling representative of all sections of society. On March 30th, we hosted our first public event - an 24 The Exclusion Act: British East and South opportunity for all those involved to spell out their A starting point for effective representation are the East Asians in British Cinema visions for the journal and answer your questions. As “protected characteristics” defined by the Equality Act Chi Thai and Delphine Lievens Editor, I chaired a wide-ranging conversation on ‘Race 2010 including, but not limited to, race, gender, and the British Media’ with Sir Lenny Henry, Leah sexuality, and disability, as well as their intersections. 38 The Problem with ‘Urban’ Cowan, and Marcus Ryder. Our discussions and the We recognise that definitions of diversity and Nina Robinson responses to illuminating audience interventions gave representation are dynamic and constantly evolving 44 Sian Vasey - disability pioneer inside us a theme that runs through this issue - capturing and our content will aim to reflect this. -

Shakespeare, Madness, and Music

45 09_294_01_Front.qxd 6/18/09 10:03 AM Page i Shakespeare, Madness, and Music Scoring Insanity in Cinematic Adaptations Kendra Preston Leonard THE SCARECROW PRESS, INC. Lanham • Toronto • Plymouth, UK 2009 46 09_294_01_Front.qxd 6/18/09 10:03 AM Page ii Published by Scarecrow Press, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 http://www.scarecrowpress.com Estover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom Copyright © 2009 by Kendra Preston Leonard All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Leonard, Kendra Preston. Shakespeare, madness, and music : scoring insanity in cinematic adaptations, 2009. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8108-6946-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8108-6958-5 (ebook) 1. Shakespeare, William, 1564–1616—Film and video adaptations. 2. Mental illness in motion pictures. 3. Mental illness in literature. I. Title. ML80.S5.L43 2009 781.5'42—dc22 2009014208 ™ ϱ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Printed -

RED VELVET: Know-The-Show Guide

The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey RED VELVET: Know-the-Show Guide Red Velvet by Lolita Chakrabarti Know-the-Show Audience Guide researched and written by the Education Department of The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey Artwork: Scott McKowen The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey RED VELVET: Know-the-Show Guide In This Guide – About the Playwright: Lolita Chakrabarti ................................................................................... 2 – The Life of Ira Aldridge .............................................................................................................. 3 – RED VELVET: A Short Synopsis .................................................................................................. 4 – Portrayals of Race in Shakespeare ............................................................................................. 5 – Who’s Who in the Play ............................................................................................................. 6 – British Abolition of Slavery ........................................................................................................ 7 – Acting Styles in the 19th Century .............................................................................................. 8 – Additional References Found in the Play ................................................................................... 9 – Commentary & Criticism ........................................................................................................ 10 – In this Production .................................................................................................................. -

By William Shakespeare Measure for Measure Why Give

Measure for Measure by William Shakespeare Measure for Measure Why give Welcome to our 2015 season with Measure for Measure. you me this Our Russian company were last here with The Tempest and we are delighted to be back. We are particularly grateful to shame? Evgeny Pisarev and Anna Volk of the Pushkin Theatre in Moscow, without whom this production would not have been possible. Act III Scene I Thanks also to Toni Racklin, Leanne Cosby, and the entire team at the Barbican, London for their continued enthusiasm and support, and to Katy Snelling and Louise Chantal at the Oxford Playhouse. We’d also like to thank our other co-producers, Les Gémeaux/ Sceaux/Scène Nationale, in Paris, and Centro Dramático Nacional, in Madrid, as well as Arts Council England. We do hope you enjoy the show… Declan Donnellan and Nick Ormerod Petr Rykov & Company 1 2 3 Cheek by Jowl in Russia In 1986, Russian theatre director Lev Dodin of Valery Shadrin, commissioned Donnellan invited Donnellan and Ormerod to visit his and Ormerod to form their own company of company in Leningrad. Ten years later, they Russian actors in Moscow. This sister company 4 5 6 directed and designed The Winter’s Tale performs in Russia and internationally and its for the Maly Drama Theatre, which is still current repertoire includes Boris Godunov running in St. Petersburg. Throughout the by Pushkin, Twelfth Night and The Tempest 1990s the Russian Theatre Confederation by Shakespeare, and Three Sisters by Anton regularly invited Cheek by Jowl to Moscow Chekhov. Measure for Measure is Cheek as part of the Chekhov International Theatre by Jowl’s first co-production with Moscow’s Festival, and this relationship intensified in Pushkin Theatre. -

Programme for Cheek by Jowl's Production of the Changeling

What does a cheek suggest – and what a jowl? When the rough is close to the smooth, the harsh to the gentle, the provocative to the welcoming, this company’s very special flavour appears. Over the years, Declan and Nick have opened up bold and innovative ways of work and of working in Britain and across the world. They have proved again and again Working on A Family Affair in 1988 that theatre begins and ends with opposites that seem Nick Ormerod Declan Donnellan irreconcilable until they march Nick Ormerod is joint Artistic Director of Cheek by Jowl. Declan Donnellan is joint Artistic Director of Cheek by Jowl. cheek by jowl, side by side. He trained at Wimbledon School of Art and has designed all but one of Cheek by As Associate Director of the National Theatre, his productions include Fuente Ovejuna Peter Brook Jowl’s productions. Design work in Russia includes; The Winter’s Tale (Maly Theatre by Lope de Vega, Sweeney Todd by Stephen Sondheim, The Mandate by Nikolai Erdman, of St Petersburg), Boris Godunov, Twelfth Night and Three Sisters (with Cheek by Jowl’s and both parts of Angels in America by Tony Kushner. For the Royal Shakespeare Company sister company in Moscow formed by the Russian Theatre Confederation). In 2003 he has directed The School for Scandal, King Lear (as the first director of the RSC Academy) he designed his first ballet, Romeo and Juliet, for the Bolshoi Ballet, Moscow. and Great Expectations. He has directed Le Cid by Corneille in French, for the Avignon Festival, Falstaff by Verdi for the Salzburg Festival and Romeo and Juliet for the Bolshoi He has designed Falstaff (Salzburg Festival), The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny Ballet, Moscow, becoming the first stage director to work with the Bolshoi Ballet since 1938.