1 Othello, Presented by the Royal National Theatre at the Olivier

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Five Children and It

Pathé FIVE CHILDREN AND IT Press pack Released Friday 15 October 2004 - Scotland Only Released Friday 22 October 2004 - Nationwide For further information please contact: Emily Carr [email protected] Victoria Keeble [email protected] Bella Gubay [email protected] 020 7426 5700 Pathé FIVE CHILDREN AND IT Press pack Capitol Films and the UK Film Council present in association with the Isle of Man Film Commission and in association with Endgame Entertainment a Jim Henson Company Production a Capitol Films / Davis Films Production Written by: David Solomons Produced by: Nick Hirschkorn Lisa Henson Samuel Hadida Directed by: John Stephenson FIVE CHILDREN AND IT Cast List It .............................................................................. Eddie Izzard Cyril......................................................................... Jonathan Bailey Anthea...................................................................... Jessica Claridge Robert ...................................................................... Freddie Highmore Jane.......................................................................... Poppy Rogers The Lamb................................................................. Alec & Zak Muggleton Horace...................................................................... Alexander Pownall Uncle Albert............................................................. Kenneth Branagh Martha...................................................................... Zoë Wanamaker Father...................................................................... -

Hamlet-Production-Guide.Pdf

ASOLO REP EDUCATION & OUTREACH PRODUCTION GUIDE 2016 Tour PRODUCTION GUIDE By WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE ASOLO REP Adapted and Directed by JUSTIN LUCERO EDUCATION & OUTREACH TOURING SEPTEMBER 27 - NOVEMBER 22 ASOLO REP LEADERSHIP TABLE OF CONTENTS Producing Artistic Director WHAT TO EXPECT.......................................................................................1 MICHAEL DONALD EDWARDS WHO CAN YOU TRUST?..........................................................................2 Managing Director LINDA DIGABRIELE PEOPLE AND PLOT................................................................................3 FSU/Asolo Conservatory Director, ADAPTIONS OF SHAKESPEARE....................................................................5 Associate Director of Asolo Rep GREG LEAMING FROM THE DIRECTOR.................................................................................6 SHAPING THIS TEXT...................................................................................7 THE TRAGEDY OF HAMLET CREATIVE TEAM FACT IN THE FICTION..................................................................................9 Director WHAT MAKES A GHOST?.........................................................................10 JUSTIN LUCERO UPCOMING OPPORTUNITIES......................................................................11 Costume Design BECKI STAFFORD Properties Design MARLÈNE WHITNEY WHAT TO EXPECT Sound Design MATTHEW PARKER You will see one of Shakespeare’s most famous tragedies shortened into a 45-minute Fight Choreography version -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

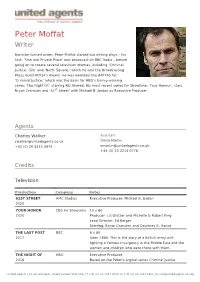

Peter Moffat Writer

Peter Moffat Writer Barrister turned writer, Peter Moffat started out writing plays – his first, ‘Fine and Private Place’ was broadcast on BBC Radio – before going on to create several television dramas, including ‘Criminal Justice, ‘Silk’ and ‘North Square,’ which he won the Broadcasting Press Guild Writer’s Award. He was awarded two BAFTAS for ‘Criminal Justice,’ which was the basis for HBO’s Emmy-winning series ‘The Night Of,’ starring Riz Ahmed. His most recent series for Showtime, ‘Your Honour,’ stars Bryan Cranston and ‘61st Street’ with Michael B. Jordan as Executive Producer. Agents Charles Walker Assistant [email protected] Olivia Martin +44 (0) 20 3214 0874 [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0778 Credits Television Production Company Notes 61ST STREET AMC Studios Executive Producer: Michael B. Jordan 2020 YOUR HONOR CBS for Showtime 10 x 60 2020 Producer: Liz Glotzer and Michelle & Robert King Lead Director: Ed Berger Starring: Bryan Cranston and Courtney B. Vance THE LAST POST BBC 6 x 60 2017 Aden 1965. This is the story of a British army unit fighting a Yemeni insurgency in the Middle East and the women and children who were there with them. THE NIGHT OF HBO Executive Producer 2016 Based on the Peter's orginal series Criminal Justice United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes UNDERCOVER BBC1 6 x60' with Sophie Okonedo and Adrian Lester, Denis 2015 Haysbert Director James Hawes, Exec Producer Peter Moffat THE VILLAGE series Company Pictures 6 x 60' with John Simm, Maxine Peake, Juliet Stevenson 1 / BBC1 Producer: Emma Burge; Director: Antonia Bird 2013 SILK 2 BBC1 6 x 60' With Maxine Peake, Rupert Penry Jones, Frances 2012 Barber, and Neil Stuke Producer: Richard Stokes; Directors: Alice Troughton, Jeremy Webb, Peter Hoar SILK BBC1 6 x 60' 2011 With Maxine Peake, Rupert Penry Jones, Natalie Dormer, Tom Hughes and Neil Stuke. -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

The York Realist

Press Release Tuesday 24 October 2017 DONMAR WAREHOUSE AND SHEFFIELD THEATRES ANNOUNCE FULL CASTING FOR THE YORK REALIST A Donmar Warehouse and Sheffield Theatres co-production By Peter Gill Donmar Warehouse: Thursday 8 February – Saturday 24 March 2018 PRESS NIGHT: Tuesday 13 February 2018 Sheffield Theatres: Tuesday 27 March – Saturday 7 April Director Robert Hastie Designer Peter McKintosh Lighting Designer Paul Pyant Sound Designer Emma Laxton Composer Richard Taylor Full cast includes Jonathan Bailey, Ben Batt, Lucy Black, Brian Fletcher, Lesley Nicol, Katie West and Matthew Wilson. The Donmar Warehouse and Sheffield Theatres today announce full casting for Donmar Associate Director and Sheffield Theatres Artistic Director Robert Hastie’s new revival of Peter Gill’s modern masterpiece The York Realist. Jonathan Bailey joins the cast as John, opposite the previously announced Ben Batt who will play George. Full casting also includes Lucy Black, Brian Fletcher, Lesley Nicol, Katie West and Matthew Wilson. ‘I live here. I live here. You can’t see that, though. You can’t see it. This is where I live. Here.’ A cottage, 1960s Yorkshire. The York Mystery plays are in rehearsal. Farmhand George strains against his roots as a new world opens up to him. Peter Gill’s influential play about two young men in love is a touching reflection on the rival forces of family, class and longing. Donmar Associate Robert Hastie returns for this timely revival from one of our greatest living playwrights, following his previous productions My Night with Reg and Splendour. Making theatre accessible to as many people as possible remains at the heart of the Donmar’s mission. -

James Strong Director

James Strong Director Agents Michelle Archer Assistant Grace Baxter [email protected] 020 3214 0991 Credits Television Production Company Notes CRIME Buccaneer/Britbox Lead Director and Executive Producer. 2021 Episodes 1-3. Writer: Irvine Welsh, based on his novel by the same name. Producer: David Blair. Executive producers: Irvine Welsh, Dean Cavanagh, Dougray Scott andTony Wood. VIGIL World Productions / BBC One Lead Director and Executive Producer. 2019 - 2020 Episodes 1- 3. Starring Suranne Jones, Rose Leslie, Shaun Evans. Writer: Tom Edge. Executive Producer: Simon Heath. United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes LIAR 2 Two Brothers/ ITV Lead Director and Executive Producer. 2019 Episodes 1-3. Writers: Jack and Harry Williams Producer: James Dean Executive Producer: Chris Aird Starring: Joanne Froggatt COUNCIL OF DADS NBC/ Jerry Bruckheimer Pilot Director and Executive Producer. 2019 Television/ Universal TV Inspired by the best-selling memoir of Bruce Feiler. Series ordered by NBC. Writers: Tony Phelan, Joan Rater. Producers: James Oh, Bruce Feiler. Exec Producers: Jerry Bruckheimer, Jonathan Littman, KristieAnne Read, Tony Phelan, Joan Rater. VANITY FAIR Mammoth/Amazon/ITV Lead Director and Executive Producer. 2017 - 2018 Episodes 1,2,3,4,5&7 Starring Olivia Cooke, Simon Russell Beale, Martin Clunes, Frances de la Tour, Suranne Jones. Writer: Gwyneth Hughes. Producer: Julia Stannard. Exec Producers: Gwyneth Hughes, Damien Timmer, Tom Mullens. LIAR ITV/Two Brothers Pictures Lead Director and Executive Producer. 2016 - 2017 Episodes 1 to 3. Writers: Harry and Jack Williams. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 88Th Academy Awards

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 88TH ACADEMY AWARDS ADULT BEGINNERS Actors: Nick Kroll. Bobby Cannavale. Matthew Paddock. Caleb Paddock. Joel McHale. Jason Mantzoukas. Mike Birbiglia. Bobby Moynihan. Actresses: Rose Byrne. Jane Krakowski. AFTER WORDS Actors: Óscar Jaenada. Actresses: Marcia Gay Harden. Jenna Ortega. THE AGE OF ADALINE Actors: Michiel Huisman. Harrison Ford. Actresses: Blake Lively. Kathy Baker. Ellen Burstyn. ALLELUIA Actors: Laurent Lucas. Actresses: Lola Dueñas. ALOFT Actors: Cillian Murphy. Zen McGrath. Winta McGrath. Peter McRobbie. Ian Tracey. William Shimell. Andy Murray. Actresses: Jennifer Connelly. Mélanie Laurent. Oona Chaplin. ALOHA Actors: Bradley Cooper. Bill Murray. John Krasinski. Danny McBride. Alec Baldwin. Bill Camp. Actresses: Emma Stone. Rachel McAdams. ALTERED MINDS Actors: Judd Hirsch. Ryan O'Nan. C. S. Lee. Joseph Lyle Taylor. Actresses: Caroline Lagerfelt. Jaime Ray Newman. ALVIN AND THE CHIPMUNKS: THE ROAD CHIP Actors: Jason Lee. Tony Hale. Josh Green. Flula Borg. Eddie Steeples. Justin Long. Matthew Gray Gubler. Jesse McCartney. José D. Xuconoxtli, Jr.. Actresses: Kimberly Williams-Paisley. Bella Thorne. Uzo Aduba. Retta. Kaley Cuoco. Anna Faris. Christina Applegate. Jennifer Coolidge. Jesica Ahlberg. Denitra Isler. 88th Academy Awards Page 1 of 32 AMERICAN ULTRA Actors: Jesse Eisenberg. Topher Grace. Walton Goggins. John Leguizamo. Bill Pullman. Tony Hale. Actresses: Kristen Stewart. Connie Britton. AMY ANOMALISA Actors: Tom Noonan. David Thewlis. Actresses: Jennifer Jason Leigh. ANT-MAN Actors: Paul Rudd. Corey Stoll. Bobby Cannavale. Michael Peña. Tip "T.I." Harris. Anthony Mackie. Wood Harris. David Dastmalchian. Martin Donovan. Michael Douglas. Actresses: Evangeline Lilly. Judy Greer. Abby Ryder Fortson. Hayley Atwell. ARDOR Actors: Gael García Bernal. Claudio Tolcachir. -

Fiona Lindsay [email protected] 07836767487

Fiona Lindsay [email protected] 07836767487 Personal Details Height - 5’8 Build – Slim Eyes – Green/Blue Hair – Dark Brown Accent – Neutral/Scottish Voice – Warm, assured, calming Other languages –French, Italian, Spanish Skills – Interviewing, Presenting, Writing, Ideas Development and Programming, Producing, Acting, Media Training, Theatre Practitioner Expert in – All aspects of theatre performance, Shakespeare Radio Dexter and Dodd for BBC Radio 4 produced by Culture Wise – Critics Choice, Pick of the Week –writer and presenter Character Assassins for BBC Radio 4 produced by Culture Wise – Critics Choice, Pick of the week –writer and presenter 3 Ideas in development with Culture Wise for BBC Radio 4 Television Interviewing Evening Standards Theatre Awards – Special Awards Interviews with Alan Bennett, Eileen Aitkins, Trevor Nunn, Richard Eyre, Adrian Lester, Richard Bean, Howard Brenton, Ben Wishaw, Clare Higgins, Anna Chancellor Sky Arts 1 – Interview with Julian Clary – Hay Sessions Sky Arts 1 – Interview with Joss Ackland – Hay Sessions Trading Places – CBBC Behind The Scenes At The RSC – Channel Four Shakespeare In The 21st Century – RESA TV ( USA) Live event Interviewing –full list attached Face to Face – own show, Arts Theatre, West End – Michael Parkinson, Alison Steadman, Raymond Blanc, Stephen Mangan, Juliet Stevenson, David Baddiel, Julian Clary, Sandi Toksvig Cheltenham Literature Festival – recent interviews include – Rupert Everett, Ken Dodd, Paul O’Grady, Patricia Hodge, Sandi Toksvig, Ben Fogle, Stephen -

ENGL August Intersession 2021 Course Description Packet

Undergraduate Course Description Packet August Intersession 2021 Updated: 3/16/21 ENGL 4933-002, Studies in Popular Culture and Popular Genres: Shakespeare in Film Instructor: D. Stephens Textbooks Required: Each student must have a subscription to Prime Video; if timed correctly, this may be obtained as a free one-month trial that covers the dates of the course. Information is here, under “See More Plans” (three lines below the orange “Try Prime” button): https://www.amazon.com/amazonprime?_encoding=UTF8&pd_rd_r=ce6f99f1-b9cb-4ff6-85fc-d8 0d65691ced&pd_rd_w=zi5Kz&pd_rd_wg=7XCJZ&qid=1601330401 Ed. Greenblatt, Stephen, The Norton Shakespeare eBook. This required text will appear on Blackboard as an e-book at the start of the semester. The price is being negotiated, but it will be around $35. Your student account will be charged approximately a week after the semester begins. If you already have a copy of the complete Norton Shakespeare, or of a recent edition of the Riverside or Pelican complete Shakespeare, we can arrange for you to opt out of having your student account charged Description: We will read four plays by Shakespeare and watch many film adaptations of these works—some at full length and many more as clips. Here is a sampling: we will analyze Asta Nielsen’s 1921 Hamlet starring herself, and we will compare modern Hamlets played by David Tennant, Patrick Stewart, Benedict Cumberbatch, Adrian Lester, and Andrew Scott. We will look at selections from Aki Kaurismaki’s Finnish Hamlet Goes Business and Kurosawa’s The Bad Sleep Well. We will view The Tempest in a science-fiction adaptation and in a stop-motion puppet production. -

The Journal of Media and Diversity Issue 02 Summer 2021

Sir Lenny Henry, Amma Asante, Afua Hirsch, Kurt Barling, Chi Thai and Delphine Lievens, Nina Robinson, David Hevey, Melanie Gray, Debbie Christie, Gary Younge, Adrian Lester, So Mayer, Siobhán McGuirk, Selina Nwulu, Ciaran Thapar The Journal of Media and Diversity Issue 02 Summer 2021 1 REPRESENTOLOGY THE JOURNAL OF MEDIA AND DIVERSITY ISSUE 02 SUMMER 2021 REPRESENTOLOGY CONTENTS EDITORIAL The Journal of Media and Diversity 04 Developing Film Welcome to Issue Two of Representology - Sir Lenny Henry and Amma Asante The Journal of Media and Diversity. Since we Editorial Mission Statement interview. launched, many of you have shared 14 Finding My Voice encouraging words and ideas on how to help Welcome to Representology, a journal Afua Hirsch create a media more reflective of modern dedicated to research and best-practice 18 Putting the Black into Britain Britain. perspectives on how to make the media more Professor Kurt Barling representative of all sections of society. On March 30th, we hosted our first public event - an 24 The Exclusion Act: British East and South opportunity for all those involved to spell out their A starting point for effective representation are the East Asians in British Cinema visions for the journal and answer your questions. As “protected characteristics” defined by the Equality Act Chi Thai and Delphine Lievens Editor, I chaired a wide-ranging conversation on ‘Race 2010 including, but not limited to, race, gender, and the British Media’ with Sir Lenny Henry, Leah sexuality, and disability, as well as their intersections. 38 The Problem with ‘Urban’ Cowan, and Marcus Ryder. Our discussions and the We recognise that definitions of diversity and Nina Robinson responses to illuminating audience interventions gave representation are dynamic and constantly evolving 44 Sian Vasey - disability pioneer inside us a theme that runs through this issue - capturing and our content will aim to reflect this. -

Shakespeare, Madness, and Music

45 09_294_01_Front.qxd 6/18/09 10:03 AM Page i Shakespeare, Madness, and Music Scoring Insanity in Cinematic Adaptations Kendra Preston Leonard THE SCARECROW PRESS, INC. Lanham • Toronto • Plymouth, UK 2009 46 09_294_01_Front.qxd 6/18/09 10:03 AM Page ii Published by Scarecrow Press, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 http://www.scarecrowpress.com Estover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom Copyright © 2009 by Kendra Preston Leonard All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Leonard, Kendra Preston. Shakespeare, madness, and music : scoring insanity in cinematic adaptations, 2009. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8108-6946-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8108-6958-5 (ebook) 1. Shakespeare, William, 1564–1616—Film and video adaptations. 2. Mental illness in motion pictures. 3. Mental illness in literature. I. Title. ML80.S5.L43 2009 781.5'42—dc22 2009014208 ™ ϱ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Printed