Shakespeare's Romantic Comedies on Film

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PBS Western Reserve President's Report

PBS Western Reserve President’s Report Fall 2020 Volume 14, Issue 4 New local production spotlights area female veterans The story of female veterans is as varied as the story of females in all walks of life. The new local The PBS Western Reserve production VETERANS OF AMERICA—OUR HEROES IN UNIFORM: THEY SERVED TOO highlights many President’s Report of the challenges and successes of area women in uniform. Examples include a young mother who is published for the now serves in the Army Reserve, a young couple who are both veterans, a female general and a Northeastern Educational nurse who is in the reserves. Television of Ohio Inc. Board of Directors, major The show also speaks about Sharon Lane, a Canton resident who was the first female casualty of funders of the station the Vietnam War. In addition, it touches on female veterans’ high rate of homelessness and how and other community Summit County Executive Ilean Shapiro has gotten involved in helping homeless female veterans. The members interested in the production premiered on PBS Western Reserve on Wednesday, Nov. 11, as part of our programming for Veterans Day. organization’s activities. MASTERPIECE celebrates its 50th year! Jan. 10, 2021, marks the 50th anniversary of MASTERPIECE, the iconic PBS drama series that sparked America’s infatuation with British television. The series recently unveiled its slate of the next 1 Programming & Local unforgettable dramas. Productions Elizabeth Is Missing (Sunday, Jan. 3, at 9 pm) Glenda Jackson won a coveted BAFTA award for her role as a woman in the grip of dementia, 2 Community Outreach searching for her missing friend. -

Laura Morrod Resume

LAURA MORROD – Editor FATE Director: Lisa James Larsson. Producer: Macdara Kelleher. Starring: Abigail Cowen, Danny Griffin and Hannah van der Westhuysen. Archery Pictures / Netflix. LOVE SARAH Director: Eliza Schroeder. Producer: Rajita Shah. Starring: Grace Calder, Rupert Penry-Jones, Bill Paterson and Celia Imrie. Miraj Films / Neopol Film / Rainstar Productions. THE LAST KINGDOM (Series 4) Director: Sarah O’Gorman. Producer: Vicki Delow. Starring: Alexander Dreymon, Ian Hart, David Dawson and Eliza Butterworth. Carnival Film & Television / Netflix. THE FEED Director: Jill Robertson. Producer: Simon Lewis. Starring: Guy Burnet, Michelle Fairlye, David Thewlis and Claire Rafferty. Amazon Studios. ORIGIN Director: Mark Brozel. Executive Producers: Rob Bullock, Andy Harries and Suzanne Mackie. Producer: John Phillips. Starring: Tom Felton, Philipp Christopher and Adelayo Adedayo. Left Bank Pictures. THE GOOD KARMA HOSPITAL 2 Director: Alex Winckler. Producer: John Chapman. Starring: Amanda Redman, Amrita Acharia and Neil Morrissey. Tiger Aspect Productions. THE BIRD CATCHER Director: Ross Clarke. Producers: Lisa Black, Leon Clarance and Ross Clarke. Starring: August Diehl, Sarah-Sofie Boussnina and Laura Birn. Motion Picture Capital. BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN: IN HIS OWN WORDS Director: Nigel Cole. Producer: Des Shaw. Starring: Bruce Springsteen. Lonesome Pine Productions. 4929 Wilshire Blvd., Ste. 259 Los Angeles, CA 90010 ph 323.782.1854 fx 323.345.5690 [email protected] HUMANS (Series 2) Director: Mark Brozel. Producer: Paul Gilbert. Starring: Gemma Chan, Colin Morgan and Emily Berrington. Kudos Film and Television. AFTER LOUISE Director: David Scheinmann. Producers: Fiona Gillies, Michael Muller and Raj Sharma. Starring: Alice Sykes and Greg Wise. Scoop Films. DO NOT DISTURB Director: Nigel Cole. Producer: Howard Ella. Starring: Catherine Tate, Miles Jupp and Kierston Wareing. -

Feature Films

NOMINATIONS AND AWARDS IN OTHER CATEGORIES FOR FOREIGN LANGUAGE (NON-ENGLISH) FEATURE FILMS [Updated thru 88th Awards (2/16)] [* indicates win] [FLF = Foreign Language Film category] NOTE: This document compiles statistics for foreign language (non-English) feature films (including documentaries) with nominations and awards in categories other than Foreign Language Film. A film's eligibility for and/or nomination in the Foreign Language Film category is not required for inclusion here. Award Category Noms Awards Actor – Leading Role ......................... 9 ........................... 1 Actress – Leading Role .................... 17 ........................... 2 Actress – Supporting Role .................. 1 ........................... 0 Animated Feature Film ....................... 8 ........................... 0 Art Direction .................................... 19 ........................... 3 Cinematography ............................... 19 ........................... 4 Costume Design ............................... 28 ........................... 6 Directing ........................................... 28 ........................... 0 Documentary (Feature) ..................... 30 ........................... 2 Film Editing ........................................ 7 ........................... 1 Makeup ............................................... 9 ........................... 3 Music – Scoring ............................... 16 ........................... 4 Music – Song ...................................... 6 .......................... -

THTR 433A/ '16 CD II/ Syllabus-9.Pages

USCSchool of Costume Design II: THTR 433A Thurs. 2:00-4:50 Dramatic Arts Fall 2016 Location: Light Lab/PDE Instructor: Terry Ann Gordon Office: [email protected]/ floating office Office Hours: Thurs. 1:00-2:00: by appt/24 hr notice Contact Info: [email protected], 818-636-2729 Course Description and Overview This course is designed to acquaint students with the requirements, process and expectations for Film/TV Costume Designers, supervisors and crew. Emphasis will be placed on all aspects of the Costume process; Design, Prep: script analysis,“scene breakdown”, continuity, research, and budgeting; Shooting schedules, and wrap. The supporting/ancillary Costume Arts and Crafts will also be discussed. Students will gain an historical overview, researching a variety of designers processes, aesthetics and philosophies. Viewing films and film clips will support critique and class discussion. Projects focused on specific design styles and varied media will further support an overview of techniques and concepts. Current production procedures, vocabulary and technology will be covered. We will highlight those Production departments interacting closely with the Costume Department. Time permitting, extra-curricular programs will include rendering/drawing instruction, select field trips, and visiting TV/Film professionals. Students will be required to design a variety of projects structured to enhance their understanding of Film/TV production, concept, style and technique . Learning Objectives The course goal is for students to become familiar with the fundamentals of costume design for TV/Film. They will gain insight into the protocol and expectations required to succeed in this fast paced industry. We will touch on the multiple variations of production formats: Music Video, Tv: 4 camera vs episodic, Film, Commercials, Styling vs Costume Design. -

YOUR UNIVERSITY SURREY.AC.UK 3 Welcome Community News

Spring 2017 News from the University of Surrey for Guildford residents SURREY.AC.UK UNIVERSITYOFSURREY UNIOFSURREY Your invitation to WON DER 13 May 2017 11am - 5pm University of Surrey, Guildford Please register via: surrey.ac.uk/festivalofwonder MUSIC · FOOD · TALKS · SPORT · DISCOVERY · WONDER Incorporating FREE Penelope Keith, DBE Community Reps scheme Festival ofFEST Wonder Spring on campus Guest Editor p2 Your view counts p5 Celebrating 50 years p11 Meet the team p12 2. The University’s 50th Anniversary celebrations 1. Waving flags on Guildford High Street 2. Mayor of Guildford, Councillor Gordon Jackson (left) and Vice-Chancellor, Professor Max Lu (right) 3. Folarin Oyeleye (left) and Tamsey Baker (right) 1. 3. Celebrating 50 years at home in Guildford The bells of Guildford Cathedral rang out on 9 September 2016 to mark the beginning of the University of Surrey’s 50th Anniversary year, celebrating half a century of calling Guildford ‘home’. The University’s Royal the cobbles of Guildford In the 50 years since setting Residents of Guildford and Charter was signed in 1966, High Street, adorned with up home on Stag Hill, the surrounding area are establishing the University banners and brought to the University has been warmly invited to join the in Guildford from its roots in life by the waving of blue warmly welcomed as part University as it ends its 50th Battersea, London. Exactly and gold flags, and made of the local community Anniversary celebrations 50 years later, bells pealed their way up to Holy in Guildford. Its staff and with a bang, in the form of across Battersea and ended Trinity Church. -

Hamlet-Production-Guide.Pdf

ASOLO REP EDUCATION & OUTREACH PRODUCTION GUIDE 2016 Tour PRODUCTION GUIDE By WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE ASOLO REP Adapted and Directed by JUSTIN LUCERO EDUCATION & OUTREACH TOURING SEPTEMBER 27 - NOVEMBER 22 ASOLO REP LEADERSHIP TABLE OF CONTENTS Producing Artistic Director WHAT TO EXPECT.......................................................................................1 MICHAEL DONALD EDWARDS WHO CAN YOU TRUST?..........................................................................2 Managing Director LINDA DIGABRIELE PEOPLE AND PLOT................................................................................3 FSU/Asolo Conservatory Director, ADAPTIONS OF SHAKESPEARE....................................................................5 Associate Director of Asolo Rep GREG LEAMING FROM THE DIRECTOR.................................................................................6 SHAPING THIS TEXT...................................................................................7 THE TRAGEDY OF HAMLET CREATIVE TEAM FACT IN THE FICTION..................................................................................9 Director WHAT MAKES A GHOST?.........................................................................10 JUSTIN LUCERO UPCOMING OPPORTUNITIES......................................................................11 Costume Design BECKI STAFFORD Properties Design MARLÈNE WHITNEY WHAT TO EXPECT Sound Design MATTHEW PARKER You will see one of Shakespeare’s most famous tragedies shortened into a 45-minute Fight Choreography version -

Press Release

Press Release Unique collaboration with RSC to mark 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death Shakespeare in Art: Tempests, Tyrants and Tragedy 19 March ‐ 19 June 2016 Compton Verney, Warwickshire Already hailed as one of 2016’s must‐see exhibitions, Shakespeare in Art: Tempests, Tyrants and Tragedy is a landmark collaboration with the Royal Shakespeare Company commemorating the 400th anniversary of the bard’s death. A master of dramatising human emotions in their myriad forms, Shakespeare’s plays have in turn inspired countless artists. Shakespeare in Art: Tempests, Tyrants and Tragedy will focus on those pivotal Shakespeare plays which have motivated artists across the ages – from Sargent, Fuseli, Rossetti, Blake, Watts and Romney to Karl Weschke, Kate Tempest and Tom Hunter – exploring the enduring appeal of the Elizabethan playwright. This exhibition offers an exceptional opportunity for both art and theatre lovers to reimagine Shakespeare’s works through a unique series of multi‐media, multi‐sensory encounters; including painting, photography, projection, sound and light. Using specially commissioned audio drawing on excerpts from Shakespeare's plays, leading RSC actors will bring to life scenes from some of the major paintings. Uniquely for an art gallery, the exhibition will be designed by the Royal Shakespeare Company’s Director of Design, Stephen Brimson Lewis. Over seventy works – including paintings, drawings, engravings, woodcuts and photos – have been sourced from across the UK for this remarkable show, taking place just nine miles away from Shakespeare’s birthplace, Stratford‐upon‐Avon. Works will travel to Compton Verney from Bolton, Birmingham, Edinburgh and York, plus Tate and the V&A in London and the show will also include a number of key works from the RSCS’s own, rarely publicly displayed art collection. -

ROSALIND-Film-Links

THE PLAY “AS YOU LIKE IT” THE WOMAN ROSALIND SOME LINKS FOR YOUR VIEWING PLEASURE YOUTUBE…. FILM PRODUCTION TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX (1936) Directed by Paul Czinner Laurence Olivier, Elisabeth Bergner, Sophie Stewart With English Captions: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wFChichBoPI&t=16s Without English Captions: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RxBwHQSbUdY&list=RDCMUCWNH6WeWgwMaWbO_ 5VfhiTQ&start_radio=1&t=24 BBC – THE OPEN UNIVERSITY “AS YOU LIKE IT” DOCUMENTARY (2016) Award-winning British Actress Fiona Shaw Lectures, Scene Study with Exercises https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1bTlH-EQSJE&t=2202s FULL AMATEUR PRODUCTIONS THE PUBLIC THEATER OF MINNESOTA SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL (2013) Filmed Outdoor Stage Production https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dDVnVpgzG5U&t=6848s SHAKESPEARE BY-THE-SEA (2015) Filmed Live Outdoor Stage Production https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZTSaCh02s8U&list=PLH0M7jdxVB3vfSQjS6gAMm6M3h Ox6cXP-&index=25 AUDIO RECORDING LIBRIVOX AUDIOBOOKS (2019) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hhcLW0FaCBk OREGON SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL (1950) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8yOhKvUtF3c&t=5539s KANOPY- FREE Through many Maine Public Libraries with Library card FILM PRODUCTION THE BBC SERIES – COMPLETE PLAYS OF SHAKESPEARE (1978) Directed by Basil Coleman Helen Mirren, Brian Stirner, Richard Pasco AMAZON PRIME VIDEO…… FILM PRODUCTIONS ROYAL SHAKESPEARE COMPANY (2019) Directed by Kimberly Sykes & Robert Lough Lucy Phelps , Antony Byrne , Sophie Khan Levy ROYAL SHAKESPEARE COMPANY (2010) Directed by Michael Boyd Jonjo O'Neill , Katy Stephens -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

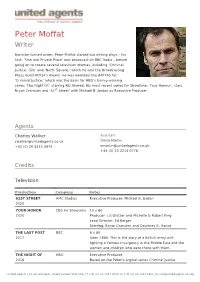

Peter Moffat Writer

Peter Moffat Writer Barrister turned writer, Peter Moffat started out writing plays – his first, ‘Fine and Private Place’ was broadcast on BBC Radio – before going on to create several television dramas, including ‘Criminal Justice, ‘Silk’ and ‘North Square,’ which he won the Broadcasting Press Guild Writer’s Award. He was awarded two BAFTAS for ‘Criminal Justice,’ which was the basis for HBO’s Emmy-winning series ‘The Night Of,’ starring Riz Ahmed. His most recent series for Showtime, ‘Your Honour,’ stars Bryan Cranston and ‘61st Street’ with Michael B. Jordan as Executive Producer. Agents Charles Walker Assistant [email protected] Olivia Martin +44 (0) 20 3214 0874 [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0778 Credits Television Production Company Notes 61ST STREET AMC Studios Executive Producer: Michael B. Jordan 2020 YOUR HONOR CBS for Showtime 10 x 60 2020 Producer: Liz Glotzer and Michelle & Robert King Lead Director: Ed Berger Starring: Bryan Cranston and Courtney B. Vance THE LAST POST BBC 6 x 60 2017 Aden 1965. This is the story of a British army unit fighting a Yemeni insurgency in the Middle East and the women and children who were there with them. THE NIGHT OF HBO Executive Producer 2016 Based on the Peter's orginal series Criminal Justice United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes UNDERCOVER BBC1 6 x60' with Sophie Okonedo and Adrian Lester, Denis 2015 Haysbert Director James Hawes, Exec Producer Peter Moffat THE VILLAGE series Company Pictures 6 x 60' with John Simm, Maxine Peake, Juliet Stevenson 1 / BBC1 Producer: Emma Burge; Director: Antonia Bird 2013 SILK 2 BBC1 6 x 60' With Maxine Peake, Rupert Penry Jones, Frances 2012 Barber, and Neil Stuke Producer: Richard Stokes; Directors: Alice Troughton, Jeremy Webb, Peter Hoar SILK BBC1 6 x 60' 2011 With Maxine Peake, Rupert Penry Jones, Natalie Dormer, Tom Hughes and Neil Stuke. -

Completeandleft Felix ,Adler ,Educator ,Ethical Culture Ferrán ,Adrià ,Chef ,El Bulli FA,F

MEN WOMEN 1. FA Frankie Avalon=Singer, actor=18,169=39 Fiona Apple=Singer-songwriter, musician=49,834=26 Fred Astaire=Dancer, actor=30,877=25 Faune A.+Chambers=American actress=7,433=137 Ferman Akgül=Musician=2,512=194 Farrah Abraham=American, Reality TV=15,972=77 Flex Alexander=Actor, dancer, Freema Agyeman=English actress=35,934=36 comedian=2,401=201 Filiz Ahmet=Turkish, Actress=68,355=18 Freddy Adu=Footballer=10,606=74 Filiz Akin=Turkish, Actress=2,064=265 Frank Agnello=American, TV Faria Alam=Football Association secretary=11,226=108 Personality=3,111=165 Flávia Alessandra=Brazilian, Actress=16,503=74 Faiz Ahmad=Afghan communist leader=3,510=150 Fauzia Ali=British, Homemaker=17,028=72 Fu'ad Aït+Aattou=French actor=8,799=87 Filiz Alpgezmen=Writer=2,276=251 Frank Aletter=Actor=1,210=289 Frances Anderson=American, Actress=1,818=279 Francis Alexander+Shields= =1,653=246 Fernanda Andrade=Brazilian, Actress=5,654=166 Fernando Alonso=Spanish Formula One Fernanda Andrande= =1,680=292 driver.=63,949=10 France Anglade=French, Actress=2,977=227 Federico Amador=Argentinean, Actor=14,526=48 Francesca Annis=Actress=28,385=45 Fabrizio Ambroso= =2,936=175 Fanny Ardant=French actress=87,411=13 Franco Amurri=Italian, Writer=2,144=209 Firoozeh Athari=Iranian=1,617=298 Fedor Andreev=Figure skater=3,368=159 ………… Facundo Arana=Argentinean, Actor=59,952=11 Frickin' A Francesco Arca=Italian, Model=2,917=177 Fred Armisen=Actor=11,503=68 Frank ,Abagnale ,Criminal ,Catch Me If You Can François Arnaud=French Canadian actor=9,058=86 Ferhat ,Abbas ,Head of State ,President of Algeria, 1962-63 Fábio Assunção=Brazilian actor=6,802=99 Floyd ,Abrams ,Attorney ,First Amendment lawyer COMPLETEandLEFT Felix ,Adler ,Educator ,Ethical Culture Ferrán ,Adrià ,Chef ,El Bulli FA,F. -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994.