I F SOUTH INDIAN MUSIC,'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Music Academy, Madras 115-E, Mowbray’S Road

Tyagaraja Bi-Centenary Volume THE JOURNAL OF THE MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS A QUARTERLY DEVOTED TO THE ADVANCEMENT OF THE SCIENCE AND ART OF MUSIC Vol. XXXIX 1968 Parts MV srri erarfa i “ I dwell not in Vaikuntha, nor in the hearts of Yogins, nor in the Sun; (but) where my Bhaktas sing, there be I, Narada l ” EDITBD BY V. RAGHAVAN, M.A., p h .d . 1968 THE MUSIC ACADEMY, MADRAS 115-E, MOWBRAY’S ROAD. MADRAS-14 Annual Subscription—Inland Rs. 4. Foreign 8 sh. iI i & ADVERTISEMENT CHARGES ►j COVER PAGES: Full Page Half Page Back (outside) Rs. 25 Rs. 13 Front (inside) 20 11 Back (Do.) „ 30 „ 16 INSIDE PAGES: 1st page (after cover) „ 18 „ io Other pages (each) „ 15 „ 9 Preference will be given to advertisers of musical instruments and books and other artistic wares. Special positions and special rates on application. e iX NOTICE All correspondence should be addressed to Dr. V. Raghavan, Editor, Journal Of the Music Academy, Madras-14. « Articles on subjects of music and dance are accepted for mblication on the understanding that they are contributed solely o the Journal of the Music Academy. All manuscripts should be legibly written or preferably type written (double spaced—on one side of the paper only) and should >e signed by the writer (giving his address in full). The Editor of the Journal is not responsible for the views expressed by individual contributors. All books, advertisement moneys and cheques due to and intended for the Journal should be sent to Dr. V. Raghavan Editor. Pages. -

Towards Automatic Audio Segmentation of Indian Carnatic Music

Friedrich-Alexander-Universit¨at Erlangen-Nurnberg¨ Master Thesis Towards Automatic Audio Segmentation of Indian Carnatic Music submitted by Venkatesh Kulkarni submitted July 29, 2014 Supervisor / Advisor Dr. Balaji Thoshkahna Prof. Dr. Meinard Muller¨ Reviewers Prof. Dr. Meinard Muller¨ International Audio Laboratories Erlangen A Joint Institution of the Friedrich-Alexander-Universit¨at Erlangen-N¨urnberg (FAU) and Fraunhofer Institute for Integrated Circuits IIS ERKLARUNG¨ Erkl¨arung Hiermit versichere ich an Eides statt, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit selbstst¨andig und ohne Benutzung anderer als der angegebenen Hilfsmittel angefertigt habe. Die aus anderen Quellen oder indirekt ubernommenen¨ Daten und Konzepte sind unter Angabe der Quelle gekennzeichnet. Die Arbeit wurde bisher weder im In- noch im Ausland in gleicher oder ¨ahnlicher Form in einem Verfahren zur Erlangung eines akademischen Grades vorgelegt. Erlangen, July 29, 2014 Venkatesh Kulkarni i Master Thesis, Venkatesh Kulkarni ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Balaji Thoshkahna, whose expertise, understanding and patience added considerably to my learning experience. I appreciate his vast knowledge and skill in many areas (e.g., signal processing, Carnatic music, ethics and interaction with participants).He provided me with direction, technical support and became more of a friend, than a supervisor. A very special thanks goes out to my Prof. Dr. Meinard M¨uller,without whose motivation and encouragement, I would not have considered a graduate career in music signal analysis research. Prof. Dr. Meinard M¨ulleris the one professor/teacher who truly made a difference in my life. He was always there to give his valuable and inspiring ideas during my thesis which motivated me to think like a researcher. -

Syllabus for Post Graduate Programme in Music

1 Appendix to U.O.No.Acad/C1/13058/2020, dated 10.12.2020 KANNUR UNIVERSITY SYLLABUS FOR POST GRADUATE PROGRAMME IN MUSIC UNDER CHOICE BASED CREDIT SEMESTER SYSTEM FROM 2020 ADMISSION NAME OF THE DEPARTMENT: DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC NAME OF THE PROGRAMME: MA MUSIC DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC KANNUR UNIVERSITY SWAMI ANANDA THEERTHA CAMPUS EDAT PO, PAYYANUR PIN: 670327 2 SYLLABUS FOR POST GRADUATE PROGRAMME IN MUSIC UNDER CHOICE BASED CREDIT SEMESTER SYSTEM FROM 2020 ADMISSION NAME OF THE DEPARTMENT: DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC NAME OF THE PROGRAMME: M A (MUSIC) ABOUT THE DEPARTMENT. The Department of Music, Kannur University was established in 2002. Department offers MA Music programme and PhD. So far 17 batches of students have passed out from this Department. This Department is the only institution offering PG programme in Music in Malabar area of Kerala. The Department is functioning at Swami Ananda Theertha Campus, Kannur University, Edat, Payyanur. The Department has a well-equipped library with more than 1800 books and subscription to over 10 Journals on Music. We have gooddigital collection of recordings of well-known musicians. The Department also possesses variety of musical instruments such as Tambura, Veena, Violin, Mridangam, Key board, Harmonium etc. The Department is active in the research of various facets of music. So far 7 scholars have been awarded Ph D and two Ph D thesis are under evaluation. Department of Music conducts Seminars, Lecture programmes and Music concerts. Department of Music has conducted seminars and workshops in collaboration with Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts-New Delhi, All India Radio, Zonal Cultural Centre under the Ministry of Culture, Government of India, and Folklore Academy, Kannur. -

Icse Specimen Qp

ICSE SEMESTER 1 EXAMINATION SPECIMEN QUESTION PAPER CARNATIC MUSIC Maximum Marks: 50 Time allowed: One hour (inclusive of reading time) ALL QUESTIONS ARE COMPULSORY. The marks intended for questions are given in brackets [ ]. Select the correct option for each of the following questions. Question 1 The Music Trinities are: [1] 1. Purandara Dasa, Jayadeva, Naryana Tirta 2. Thyagaraja, Muthuswami Dikshitar, Syama Sastri 3. Veen Kuppaiar, Gopalakrishna Bharathy, Arunachala kavi 4. Gopalakrishna Bharathy, Bhadrachala Ramadas, Syama Sastri Question 2 Gita Govindam – The Jivathma and Paramathma aikya tatava was composed by: [1] 1. Thyagaraja 2. Muthuswami Dikshitar 3. Jayadeva 4. None of the above Question 3 Sympathetic Vibration is produced on: [1] 1. Veena and Violin 2. Tambura and Sitar 3. Tabla and Mridangam 4. None of the above 1 Question 4 Stringed instruments are also called as: [1] 1. Tata vadyas 2. Sushira Vadyas 3. Avanadhdha vadyas 4. Ghana Vadyas Question 5 The Ghana raga Pancharatnam by Thyagaraja are in the ragas: [1] 1. Hamsadhwani, Garudadhwani, Mayuradhwani 2. Nata, Arabhi, Goula, Sri, Varali 3. Nata, Chala Nata, Gambhira Nata 4. Kedaragoula, Narayanagoula, Goula, Kannada Goula, Ritigoula Question 6 Intensity, when the string is plucked with force and without force results in: [1] 1. Change in the pitch of the string 2. No change in the pitch of the string 3. Both 1. & 2. 4. None of the above Question 7 Panchalinga Sthala kritis are composed by: [1] 1. Thyagaraja 2. Muthuswami Dikshitar 3. Syama Sastri 4. Swati Tirunal 2 Question 8 Samudaya kritis are: [1] 1. Lalgudi Pancharatnam, Ghana raga pancharatnam, Venkateshwara Pancharatnam 2. -

Fusion Without Confusion Raga Basics Indian

Fusion Without Confusion Raga Basics Indian Rhythm Basics Solkattu, also known as konnakol is the art of performing percussion syllables vocally. It comes from the Carnatic music tradition of South India and is mostly used in conjunction with instrumental music and dance instruction, although it has been widely adopted throughout the world as a modern composition and performance tool. Similarly, the music of North India has its own system of rhythm vocalization that is based on Bols, which are the vocalization of specific sounds that correspond to specific sounds that are made on the drums of North India, most notably the Tabla drums. Like in the south, the bols are used in musical training, as well as composition and performance. In addition, solkattu sounds are often referred to as bols, and the practice of reciting bols in the north is sometimes referred to as solkattu, so the distinction between the two practices is blurred a bit. The exercises and compositions we will discuss contain bols that are found in both North and South India, however they come from the tradition of the North Indian tabla drums. Furthermore, the theoretical aspect of the compositions is distinctly from the Hindustani, (north Indian) tradition. Hence, for the purpose of this presentation, the use of the term Solkattu refers to the broader, more general practice of Indian rhythmic language. South Indian Percussion Mridangam Dolak Kanjira Gattam North Indian Percussion Tabla Baya (a.k.a. Tabla) Pakhawaj Indian Rhythm Terms Tal (also tala, taal, or taala) – The Indian system of rhythm. Tal literally means "clap". -

Rakti in Raga and Laya

VEDAVALLI SPEAKS Sangita Kalanidhi R. Vedavalli is not only one of the most accomplished of our vocalists, she is also among the foremost thinkers of Carnatic music today with a mind as insightful and uncluttered as her music. Sruti is delighted to share her thoughts on a variety of topics with its readers. Rakti in raga and laya Rakti in raga and laya’ is a swara-oriented as against gamaka- complex theme which covers a oriented raga-s. There is a section variety of aspects. Attempts have of exponents which fears that ‘been made to interpret rakti in the tradition of gamaka-oriented different ways. The origin of the singing is giving way to swara- word ‘rakti’ is hard to trace, but the oriented renditions. term is used commonly to denote a manner of singing that is of a Yo asau Dhwaniviseshastu highly appreciated quality. It swaravamavibhooshitaha carries with it a sense of intense ranjako janachittaanaam involvement or engagement. Rakti Sankarabharanam or Bhairavi? rasa raga udaahritaha is derived from the root word Tyagaraja did not compose these ‘ranj’ – ranjayati iti ragaha, ranjayati kriti-s as a cluster under the There is a reference to ‘dhwani- iti raktihi. That which is pleasing, category of ghana raga-s. Older visesha’ in this sloka from Brihaddcsi. which engages the mind joyfully texts record these five songs merely Scholars have suggested that may be called rakti. The term rakti dhwanivisesha may be taken th as Tyagaraja’ s compositions and is not found in pre-17 century not as the Pancharatna kriti-s. Not to connote sruti and that its texts like Niruktam, Vyjayanti and only are these raga-s unsuitable for integration with music ensures a Amarakosam. -

Analyzing the Melodic Structure of a Raga-Based Song

Georgian Electronic Scientific Journal: Musicology and Cultural Science 2009 | No.2(4) A Statistical Analysis Of A Raga-Based Song Soubhik Chakraborty1*, Ripunjai Kumar Shukla2, Kolla Krishnapriya3, Loveleen4, Shivee Chauhan5, Mona Kumari6, Sandeep Singh Solanki7 1, 2Department of Applied Mathematics, BIT Mesra, Ranchi-835215, India 3-7Department of Electronics and Communication Engineering, BIT Mesra, Ranchi-835215, India * email: [email protected] Abstract The origins of Indian classical music lie in the cultural and spiritual values of India and go back to the Vedic Age. The art of music was, and still is, regarded as both holy and heavenly giving not only aesthetic pleasure but also inducing a joyful religious discipline. Emotion and devotion are the essential characteristics of Indian music from the aesthetic side. From the technical perspective, we talk about melody and rhythm. A raga, the nucleus of Indian classical music, may be defined as a melodic structure with fixed notes and a set of rules characterizing a certain mood conveyed by performance.. The strength of raga-based songs, although they generally do not quite maintain the raga correctly, in promoting Indian classical music among laymen cannot be thrown away. The present paper analyzes an old and popular playback song based on the raga Bhairavi using a statistical approach, thereby extending our previous work from pure classical music to a semi-classical paradigm. The analysis consists of forming melody groups of notes and measuring the significance of these groups and segments, analysis of lengths of melody groups, comparing melody groups over similarity etc. Finally, the paper raises the question “What % of a raga is contained in a song?” as an open research problem demanding an in-depth statistical investigation. -

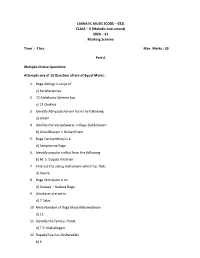

CARNATIC MUSIC (CODE – 032) CLASS – X (Melodic Instrument) 2020 – 21 Marking Scheme

CARNATIC MUSIC (CODE – 032) CLASS – X (Melodic Instrument) 2020 – 21 Marking Scheme Time - 2 hrs. Max. Marks : 30 Part A Multiple Choice Questions: Attempts any of 15 Question all are of Equal Marks : 1. Raga Abhogi is Janya of a) Karaharapriya 2. 72 Melakarta Scheme has c) 12 Chakras 3. Identify AbhyasaGhanam form the following d) Gitam 4. Idenfity the VarjyaSwaras in Raga SuddoSaveri b) GhanDharam – NishanDham 5. Raga Harikambhoji is a d) Sampoorna Raga 6. Identify popular vidilist from the following b) M. S. Gopala Krishnan 7. Find out the string instrument which has frets d) Veena 8. Raga Mohanam is an d) Audava – Audava Raga 9. Alankaras are set to d) 7 Talas 10 Mela Number of Raga Maya MalawaGoula d) 15 11. Identify the famous flutist d) T R. Mahalingam 12. RupakaTala has AksharaKals b) 6 13. Indentify composer of Navagrehakritis c) MuthuswaniDikshitan 14. Essential angas of kriti are a) Pallavi-Anuppallavi- Charanam b) Pallavi –multifplecharanma c) Pallavi – MukkyiSwaram d) Pallavi – Charanam 15. Raga SuddaDeven is Janya of a) Sankarabharanam 16. Composer of Famous GhanePanchartnaKritis – identify a) Thyagaraja 17. Find out most important accompanying instrument for a vocal concert b) Mridangam 18. A musical form set to different ragas c) Ragamalika 19. Identify dance from of music b) Tillana 20. Raga Sri Ranjani is Janya of a) Karahara Priya 21. Find out the popular Vena artist d) S. Bala Chander Part B Answer any five questions. All questions carry equal marks 5X3 = 15 1. Gitam : Gitam are the simplest musical form. The term “Gita” means song it is melodic extension of raga in which it is composed. -

1 ; Mahatma Gandhi University B. A. Music Programme(Vocal

1 ; MAHATMA GANDHI UNIVERSITY B. A. MUSIC PROGRAMME(VOCAL) COURSE DETAILS Sem Course Title Hrs/ Cred Exam Hrs. Total Week it Practical 30 mts Credit Theory 3 hrs. Common Course – 1 5 4 3 Common Course – 2 4 3 3 I Common Course – 3 4 4 3 20 Core Course – 1 (Practical) 7 4 30 mts 1st Complementary – 1 (Instrument) 3 3 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 1 (Theory) 2 2 3 Common Course – 4 5 4 3 Common Course – 5 4 3 3 II Common Course – 6 4 4 3 20 Core Course – 2 (Practical) 7 4 30 mts 1st Complementary – 2 (Instrument) 3 3 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 2 (Theory) 2 2 3 Common Course – 7 5 4 3 Common Course – 8 5 4 3 III Core Course – 3 (Theory) 3 4 3 19 Core Course – 4 (Practical) 7 3 30 mts 1st Complementary – 3 (Instrument) 3 2 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 3 (Theory) 2 2 3 Common Course – 9 5 4 3 Common Course – 10 5 4 3 IV Core Course – 5 (Theory) 3 4 3 19 Core Course – 6 (Practical) 7 3 30 mts 1st Complementary – 4 (Instrument) 3 2 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 4 (Theory) 2 2 3 Core Course – 7 (Theory) 4 4 3 Core Course – 8 (Practical) 6 4 30 mts V Core Course – 9 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts 21 Core Course – 10 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts Open Course – 1 (Practical/Theory) 3 4 Practical 30 mts Theory 3 hrs Course Work/ Project Work – 1 2 1 Core Course – 11 (Theory) 4 4 3 Core Course – 12 (Practical) 6 4 30 mts VI Core Course – 13 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts 21 Core Course – 14 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts Elective (Practical/Theory) 3 4 Practical 30 mts Theory 3 hrs Course Work/ Project Work – 2 2 1 Total 150 120 120 Core & Complementary 104 hrs 82 credits Common Course 46 hrs 38 credits Practical examination will be conducted at the end of each semester 2 MAHATMA GANDHI UNIVERSITY B. -

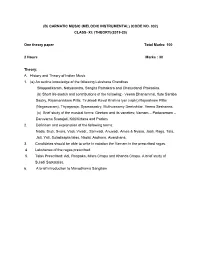

Carnatic Music (Melodic Instrumental) (Code No

(B) CARNATIC MUSIC (MELODIC INSTRUMENTAL) (CODE NO. 032) CLASS–XI: (THEORY)(2019-20) One theory paper Total Marks: 100 2 Hours Marks : 30 Theory: A. History and Theory of Indian Music 1. (a) An outline knowledge of the following Lakshana Grandhas Silappadikaram, Natyasastra, Sangita Ratnakara and Chaturdandi Prakasika. (b) Short life sketch and contributions of the following:- Veena Dhanammal, flute Saraba Sastry, Rajamanikkam Pillai, Tirukkodi Kaval Krishna lyer (violin) Rajaratnam Pillai (Nagasvaram), Thyagaraja, Syamasastry, Muthuswamy Deekshitar, Veena Seshanna. (c) Brief study of the musical forms: Geetam and its varieties; Varnam – Padavarnam – Daruvarna Svarajati, Kriti/Kirtana and Padam 2. Definition and explanation of the following terms: Nada, Sruti, Svara, Vadi, Vivadi:, Samvadi, Anuvadi, Amsa & Nyasa, Jaati, Raga, Tala, Jati, Yati, Suladisapta talas, Nadai, Arohana, Avarohana. 3. Candidates should be able to write in notation the Varnam in the prescribed ragas. 4. Lakshanas of the ragas prescribed. 5. Talas Prescribed: Adi, Roopaka, Misra Chapu and Khanda Chapu. A brief study of Suladi Saptatalas. 6. A brief introduction to Manodhama Sangitam CLASS–XI (PRACTICAL) One Practical Paper Marks: 70 B. Practical Activities 1. Ragas Prescribed: Mayamalavagowla, Sankarabharana, Kharaharapriya, Kalyani, Kambhoji, Madhyamavati, Arabhi, Pantuvarali Kedaragaula, Vasanta, Anandabharavi, Kanada, Dhanyasi. 2. Varnams (atleast three) in Aditala in two degree of speed. 3. Kriti/Kirtana in each of the prescribed ragas, covering the main Talas Adi, Rupakam and Chapu. 4. Brief alapana of the ragas prescribed. 5. Technique of playing niraval and kalpana svaras in Adi, and Rupaka talas in two degrees of speed. 6. The candidate should be able to produce all the gamakas pertaining to the chosen instrument. -

Andhra University 1 Year Diploma in (Music) Syllabus

SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATIN – ANDHRA UNIVERSITY 1st YEAR DIPLOMA IN (MUSIC) SYLLABUS (BOS approved and modified syllabus to be implemented from the admitted Batch 2012-13) Theory 100 Marks Paper I : Technical aspects of South Indian Classical Music 1. Technical Terms: a) Nada b) Sruti c) Swaras d) Swarasthanas e) Sathayi 2. Tala System: Sapta Talas, 35 Talas, Tala Dasa Prans, Chapu Tala Varieties Desadi and Madhyadi Talas 3. Musical Forms and their Lakshnas: Gitam, Varnam, Kritis, Kirtana, Padam, Ragamalika, Jasti Swaram, Swarajati, Tillana and Javali. 4. Lakshanas and Sancharas of the following Ragas: A a) Todi, b) Mayamalavagoula, c) Bhairavi, d) Kambhoji, e) Sankarabharanam f) Kalyani, g) Kharaharapriya, h) Mohana, i) Madhyamavathi j) Bilahari B. a) Dhanyasi, b) Saveri e)Vasanta d) HIndola e) Ananda Bhairavi f) Mukhari g) Kanada h) Khamas i) Begada j) Poorikalyani Paper II : Theoretical Aspects of South Indian Classical Music 100 Marks 1. Raaga and raga Lakshanam: a) Definition and Classification of ragas. b) Study of 13 Lakshanas c) ragalapana Padhathi 2. Musical Instruments and their classification 3. Special study of Tambura, Veena, Violin, Flute, Nagaswaram and Mridangam. 4. Characteristics of a composer. 5. Short biographical sketches of the following: a) Jayadeva b) Annamayya, c) Purandhara Dasa d) Narayana Tirtha e) Ramadasa f) Kshetrayya. Practical (First year) 100 Marks Paper III (Practical I) Fundamentals of Classical Music 1. a. Saraliswaras 6 b. Janta swaras 8 c. Alankaras 7 2. Gitas - 7 (Two Pillari Gitas, Two Ghanaraga Gitas, one Dhruva and one Lakshana gitam) 3. One Swarapallavi and one Swarajati 4. Five Adi Tala Varnas. -

University of Kerala Ba Music Faculty of Fine Arts Choice

UNIVERSITY OF KERALA COURSE STRUCTURE AND SYLLABUS FOR BACHELOR OF ARTS DEGREE IN MUSIC BA MUSIC UNDER FACULTY OF FINE ARTS CHOICE BASED-CREDIT-SYSTEM (CBCS) Outcome Based Teaching, Learning and Evaluation (2021 Admission onwards) 1 Revised Scheme & Syllabus – 2021 First Degree Programme in Music Scheme of the courses Sem Course No. Course title Inst. Hrs Credit Total Total per week hours credits I EN 1111 Language course I (English I) 5 4 25 17 1111 Language course II (Additional 4 3 Language I) 1121 Foundation course I (English) 4 2 MU 1141 Core course I (Theory I) 6 4 Introduction to Indian Music MU 1131 Complementary I 3 2 (Veena) SK 1131.3 Complementary course II 3 2 II EN 1211 Language course III 5 4 25 20 (English III) EN1212 Language course IV 4 3 (English III) 1211 Language course V 4 3 (Additional Language II) MU1241 Core course II (Practical I) 6 4 Abhyasaganam & Sabhaganam MU1231 Complementary III 3 3 (Veena) SK1231.3 Complementary course IV 3 3 III EN 1311 Language course VI 5 4 25 21 (English IV) 1311 Language course VII 5 4 (Additional language III ) MU1321 Foundation course II 4 3 MU1341 Core course III (Theory II) 2 2 Ragam MU1342 Core course IV (Practical II) 3 2 Varnams and Kritis I MU1331 Complementary course V 3 3 (Veena) SK1331.3 Complementary course VI 3 3 IV EN 1411 Language course VIII 5 4 25 21 (English V) 1411 Language course IX 5 4 (Additional language IV) MU1441 Core course V (Theory III) 5 3 Ragam, Talam and Vaggeyakaras 2 MU1442 Core course VI (Practical III) 4 4 Varnams and Kritis II MU1431 Complementary