1. 2015 Promises to Be an Interesting Year for Local Government, Albeit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

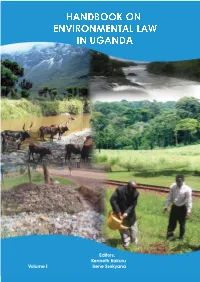

Handbook on Environmental Law in Uganda

HANDBOOK ON ENVIRONMENTAL LAW IN UGANDA Editors: Kenneth Kakuru Volume I Irene Ssekyana HANDBOOK ON ENVIRONMENTAL LAW IN UGANDA Volume I If we all did little, we would do much Second Edition February 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................................... v Forward ........................................................................................................................................................................vi Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................... viii CHAPTER ONE ............................................................................................................................................................ 1 INTRODUCTION TO ENVIRONMENTAL LAW ..................................................................................................... 1 1.1 A Brief History of Environmental Law ......................................................................................................... 1 1.1.1 Religious, Cultural and historical roots .................................................................................................. 1 1.1.2 The Green Revolution ............................................................................................................................ 2 1.1.3 Environmental Law in the United States of America -

General Scheme of Delegation to Officers

PART 3 3.2 SCHEME OF DELEGATION TO OFFICERS 1 Revised as at Council 22/10/2020 INDEX Page No. INTRODUCTION AND POWERS TO THE CHIEF 3 EXECUTIVE AND ALL DIRECTORS CHIEF EXECUTIVE’S 11 RESOURCES 17 SOCIAL CARE, HEALTH AND HOUSING 27 REGENERATION 61 TECHNICAL SERVICES 67 EDUCATION AND CHILDREN’S SERVICES 73 2 Revised as at Council 22/10/2020 1. INTRODUCTION This Scheme of Delegation is maintained under Section 100G of the Local Government Act 1972 and lists the functions that have been delegated to particular officers by either the Council or the Executive Board. These functions are delegated to officers by the Council under Sections 101 and 151 of the Local Government Act 1972 and by the Executive Board under Section 15 of the Local Government Act 2000. All Directors are authorised to make arrangements for the proper administration of the functions falling within their responsibility. 1.1 The officers described in this Scheme may authorise officers in their department/service area to exercise on their behalf, functions delegated to them. Any decisions taken under this authority shall remain the responsibility of the officer described in this Scheme and must be taken in the name of that officer, who shall remain accountable and responsible for such decisions. Each department shall maintain a record of these further delegations. 1.2 The Scheme delegates powers and duties within broad functional descriptions and includes powers and duties under all legislation present and future within those descriptions. Any reference to a specific statute includes any statutory extension or modification or re-enactment of such statute and any regulations, orders or bylaws made there under. -

2. Interpretation of Legal Requirements Under Part IV, Environment Act 1995

Guidance on Local Authority Air quality Management Interpretation of Legal Requirements 2. Interpretation of Legal Requirements under Part IV, Environment Act 1995 The purpose of this Chapter is to detail the main requirements of Part IV of the Environment Act 1995 with particular reference to the implications for local authorities to develop air quality management plans. The Chapter will expand on the details of the Act and provide further guidance on practical issues relating to assessing achievement of standards. EC and UK Legislation on Air Quality The EC Council of ministers has recently adopted a number of directives central to European air and pollution policy. The Ambient Air Quality Assessment and Management Directive establishes a framework under which the community will agree air quality limit or guide values for specified pollutants in a series of “daughter directives”. These will supersede existing air quality legislation. Under this framework directive, Member States will have to monitor levels of these pollutants and draw up and implement reduction plans for those areas in which the limit values are being or are likely to be breached. The Environment Act 1995 Part IV and the UK National Air Quality Strategy provide the principal means of carrying out the UK’s commitments under this Directive. The Integrated Pollution Prevention and Control Directive requires Member States to ensure that major industrial installations receive permits based on the Best Available Techniques for pollution control subject to technical and economic feasibility. The Integrated Pollution Control strategy in the Environmental Protection Act 1990 will form the basis of the UK implementation of this Directive. -

Scheme of Delegated Powers

Part 3 Responsibility of Functions – Scheme of Delegated Powers RESPONSIBILITY FOR FUNCTIONS DELEGATED POWERS GENERAL The Local Authorities (Functions and Responsibilities) (England) Regulations 2000 (as amended) give effect to section 13 of the Local Government Act 2000 by specifying: - (a) which functions are not to be the responsibility of the Executive (Cabinet); as specified in Schedule 1 to the Local Authorities (Functions and Responsibilities) (England) Regulations 2000 and as detailed in the Appendix to this part of the Constitution. (b) functions which may (but need not) be the responsibility of the Executive (Cabinet) (local choice functions); (c) which are to some extent the responsibility of the Executive. All other functions not so specified are to be the responsibility of the Executive. Every decision of the Cabinet, a Portfolio Holder, Committee, Sub-Committee, Working Party or Officer under delegated powers shall comply with the Council’s Constitution and in particular with its Budget and Policy Framework, Council Procedure Rules, Financial Procedure Rules and Procurement Procedure Rules and any expenditure involved is subject to such compliance. 1. RESPONSIBILITY FOR LOCAL CHOICE FUNCTIONS Local Choice functions are those, which may (but need not) be the responsibility of the Cabinet. Schedule 1 of Part 3 of the Constitution details the responsibility for those local choice functions as set out in Schedule 2 to the Local Authorities (Functions and Responsibilities) (England) Regulations 2000, as determined by the Council. 2. RESPONSIBILITY FOR COUNCIL (NON-EXECUTIVE) FUNCTIONS The roles and responsibilities of full Council are set out in Article 4 of the Constitution. The specific functions set out in Schedule 1 to the Local Authorities (Functions and Responsibilities) (England) Regulations 2000 which are retained for determination by full Council are set out in Schedule 2. -

The Environment Act 1995 (Contaminated Land Commencement and Saving Provision) (Wales) Order 2001

LC299 Cynulliad Cenedlaethol Cymru The National Assembly for Wales ADRODDIAD GAN Y PWYLLGOR DEDDFAU LEGISLATION COMMITTEE REPORT The Environment Act 1995 (Contaminated Land Commencement and Saving Provision) (Wales) Order 2001 Background This Order provides for the commencement, on 1 July 2001, of certain provisions of the Environment Act 1995 relating to contaminated land. The commenced provisions make amendments to the Environmental Protection Act 1990. A commencement and saving order to the same effect as the present order was made in respect of England on 2 February 2000, with the relevant provisions of the 1995 Act being commenced on 1 April 2000. Standing Order 11.5 No points have been identified as matters in respect of which the Committee needs to formally invite the Assembly to pay special attention under SO 11.5. General Observations Whilst it has been concluded that formal reporting under SO 11.5 is not warranted, attention is drawn to the following matters. Explanatory Note The Statutory Instrument Handbook indicates that where an Act is brought into force by more than one commencement order, the second and subsequent orders should have a note, after the Explanatory Note, listing the provisions brought into force by earlier orders. The Handbook goes on to indicate, however, that where this is impracticable, such as where listing a large number of earlier orders would result in unacceptable delay, a list of the provisions brought into force by earlier orders should be made available to enquirers, and a statement of this included after the Explanatory Note. The Handbook further indicates that where the order brings the last remaining provisions of an Act into force, this should be stated in the Explanatory Note. -

Environmental Protection Act 1990: Part 2A

www.defra.gov.uk Environmental Protection Act 1990: Part 2A Contaminated Land Statutory Guidance April 2012 © Crown copyright 2012 You may re-use this information (excluding logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ doc/open-government-licence/ or e-mail: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This document/publication is also available on the Government website at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/contaminated-land-statutory-guidance Any enquiries regarding this document/publication should be sent to us at: [email protected] This publication is available for download at www.official-documents.gov.uk. Printed in the UK for The Stationery Office Limited on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office 04/12 PB13735 Contents Ministerial Foreword ...........................................................................................................................2 Introduction .........................................................................................................................................3 Section 1: Objectives of the Part 2A regime ......................................................................................5 Section 2: Local authority inspection duties .......................................................................................6 -

Environment Bill Explanatory Notes

ENVIRONMENT BILL EXPLANATORY NOTES What these notes do These Explanatory Notes relate to the Environment Bill as introduced in the House of Commons on 30 January 2020 (Bill 9). • These Explanatory Notes have been prepared by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) in order to assist the reader of the Bill and to help inform debate on it. They do not form part of the Bill and have not been endorsed by Parliament. • These Explanatory Notes explain what each part of the Bill will mean in practice; provide background information on the development of policy; and provide additional information on how the Bill will affect existing legislation in this area. • These Explanatory Notes might best be read alongside the Bill. They are not, and are not intended to be, a comprehensive description of the Bill. Bill 9–EN 58/1 Table of Contents Subject Page of these Notes Overview of the Bill 9 Policy background 13 Exiting the European Union (EU) 13 Part 1: Environmental Governance 13 Part 2: Environmental Governance: Northern Ireland 14 Part 3: Waste and Resource Efficiency 15 Part 4: Air Quality and Environmental Recall 16 Part 5: Water 17 Part 6: Nature and Biodiversity 18 Part 7: Conservation Covenants 19 Part 8: Miscellaneous and General Provisions 19 Legal background 20 Territorial extent and application 21 Commentary on provisions of Bill 22 Part 1: Environmental Governance 22 Chapter 1: Improving the natural environment 22 Clause 1: Environmental targets 22 Clause 2: Environmental targets: particulate matter 23 Clause 3: -

Local Government Air Quality Responsibilities

BRIEFING PAPER Number CBP 8804, 25 February 2020 Local Government Air By Alex Adcock and Louise Smith Quality Responsibilities Contents: 1. Local Air Quality Management (LAQM) regime 2. Actions to improve air quality 3. Proposals for change www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 Local Government Air Quality Responsibilities Contents Summary 3 1. Local Air Quality Management (LAQM) regime 4 1.1 National Air Quality Strategy 2007 4 Local authorities in England 4 Devolved administrations 6 1.2 Air quality legislation: standards and targets 6 Air Quality Directive and regulations 6 Environment Act 1995 7 Environment (Northern Ireland) Order 2002 Part III 7 1.3 The LAQM process 8 Annual Status Reports (ASRs) Annual Progress Reports (APRs) 8 Reporting in Northern Ireland 9 Air Quality Management Areas (AQMAs) 10 Air Quality Action Plans 10 Enforcement of local authority obligations 12 Case study: Birmingham City Council 12 2. Actions to improve air quality 14 2.1 Clean Air Zone Framework (England) 14 Charging zones 15 Low emission zones (Scotland) 16 Clean Air Zone Framework for Wales 17 2.2 Smoke Control Area Framework 17 Powers to require creation or suspension of smoke control areas 17 2.3 Statutory nuisance powers 18 Exemptions from statutory nuisance 18 Enforcement 19 2.4 Planning 19 Planning conditions 20 2.5 Government funding for local authorities to improve air quality (England) 20 3. Proposals for change 22 3.1 Consultations on domestic fuel burning 22 3.2 Clean Air Strategy 2019 23 3.3 Environment Bill 2019-20 24 Local Air Quality Management (LAQM) 24 Smoke control areas 25 Statutory nuisance for smoke emissions from private dwellings 26 Contributing Authors: Gabrielle Garton Grimwood Cover page image copyright: Air Pollution Monitoring Station by Mike Quinn. -

(Legislative Competence) (Environment) Order 2010

MEMORANDUM FROM THE MINISTER FOR ENVIRONMENT, SUSTAINABILITY AND HOUSING CONSTITUTIONAL LAW: DEVOLUTION, WALES The draft National Assembly for Wales (Legislative Competence) (Environment) Order 2010 Introduction 1. The Memorandum sets out the background to the provisions in the National Assembly for Wales (Legislative Competence) (Environment) Order 2009 which confers additional legislative competence upon the National Assembly for Wales and which has been laid in accordance with SO 22.31 and explains the scope of the power requested. 2. The constitutional context to this request is set out by the Government of Wales Act 2006 (the 2006 Act) and the UK Government’s policy, contained in the White Paper “Better Governance for Wales”. Section 95 of the 2006 Act empowers Her Majesty, by Order in Council, to confer competence on the National Assembly for Wales (‘the National Assembly’) to legislate by Assembly Measure on specified Matters. These Matters may be added to Fields within Schedule 5 to the 2006 Act. Assembly Measures may make any provision which could be made by Act of Parliament, in relation to Matters, subject to the limitations provided for in Part 3 of the 2006 Act. An Order in Council under Section 95 of the 2006 Act is referred to as a Legislative Competence Order (LCO) in this memorandum. 3. The LCO confers further legislative competence on the National Assembly for Wales, in the Field of Environment (Field 6 within Schedule 5 to the 2006 Act). Attached at Annex A is a copy of Schedule 5 showing the legislative competence that the National Assembly has acquired to date. -

Environment Bill Explanatory Notes

ENVIRONMENT BILL EXPLANATORY NOTES What these notes do These Explanatory Notes relate to the Environment Bill as introduced in the House of Commons on 15 October 2019 (Bill 3). • These Explanatory Notes have been prepared by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) in order to assist the reader of the Bill and to help inform debate on it. They do not form part of the Bill and have not been endorsed by Parliament. • These Explanatory Notes explain what each part of the Bill will mean in practice; provide background information on the development of policy; and provide additional information on how the Bill will affect existing legislation in this area. • These Explanatory Notes might best be read alongside the Bill. They are not, and are not intended to be, a comprehensive description of the Bill. Bill 3–EN 57/2 Table of Contents Subject Page of these Notes Overview of the Bill 9 Policy background 13 Exiting the European Union (EU) 13 Part 1: Environmental Governance 13 Part 2: Environmental Governance: Northern Ireland 14 Part 3: Waste and Resource Efficiency 14 Part 4: Air Quality and Environmental Recall 15 Part 5: Water 17 Part 6: Nature and Biodiversity 17 Part 7: Conservation Covenants 18 Part 8: Miscellaneous and General Provisions 19 Legal background 19 Territorial extent and application 21 Commentary on provisions of Bill 23 Part 1: Environmental Governance 23 Chapter 1: Improving the natural environment 23 Clause 1: Environmental targets 23 Clause 2: Environmental targets: particulate matter 23 Clause 3: -

Legislation and Regulations

STATUTES HISTORICALY SIGNIFICANT ENGLISH STATUTES SIGNIFICANT U.S. FEDERAL LEGISLATION AND REGULATIONS STATUTORY REFERENCES IN THE ENCYCLOPEDIA ENGLISH STATUTES A B C D E F G H I-K L M N O P R S T U-Z US STATUTES Public Acts and Codes Uniform Commercial Code Annotated (USCA) State Codes AUSTRALIAN STATUTES CANADIAN STATUTES & CODES NEW ZEALAND STATUTES FRENCH CODES & LEGISLATION French Civil Code Other French Codes French Laws & Decrees OTHER CODES 1 back to the top STATUTES HISTORICALLY SIGNIFICANT ENGLISH STATUTES De Donis Conditionalibus 1285 ................................................................................................................................. 5 Statute of Quia Emptores 1290 ................................................................................................................................ 5 Statute of Uses 1536.................................................................................................................................................. 5 Statute of Frauds 1676 ............................................................................................................................................. 6 SIGNIFICANT SIGNIFICANT ENGLISH STATUTES Housing Acts ................................................................................................................................................................. 8 Land Compensation Acts ........................................................................................................................................ -

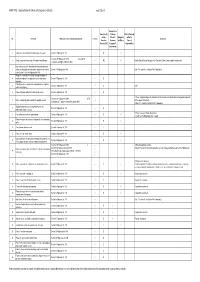

Highway Network Scheme of Delegation and Duties April 2021 V2

HNMP TA02 ‐ Highway Network Scheme of Delegation and Duties April 2021 V2 Delegation to Executive (E) Strategic District, Borough or Non- Director - Delegation or Parish No. Function Provision of Act or Statutory Instrument In Force Comments Executive Economy, to Officer Council Function (NE) Transport & Responsibility Environment 1 Powers to create footpaths and bridleways by agreement Section 25 Highways Act 1980 NE 1) Section 26 Highways Act 1980 2) Section 58 2 Compulsory powers for creation of footpaths and bridleways NE Enables Natural England to apply to the Secretary of State to make a public footpath order Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000 Duty to keep register of information with respect to maps and 3 statements deposited and declarations lodged with the Council Section 31A Highways Act 1980 Duty - The Council's Constitution Part 3 Appendix 2 under Section 31(6) of the Highways Act 1980 Response to a dedication either by certifying acceptance or 4 making a complaint to a magistrates' court to resist such a Section 37 Highways Act 1980 E dedication Authority to make a complaint by resisting dedication of publicly 5 Section 37 Highways Act 1980 E Cabco maintainable Highway 6 Power of Highway Authorities to adopt by agreement Section 38 Highways Act 1980 E 1) Power to impose charges, in connection with the clearance of accident debris, on the person responsible 1) Section 41 Highways Act 1980 2) The 7 Duty to maintain highways maintainable at public expense for the deposit of the debris Local Authority (Transport Charges)