Springer-Verlag 1842 - 1999: a Review Essay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Technology Wants / Kevin Kelly

WHAT TECHNOLOGY WANTS ALSO BY KEVIN KELLY Out of Control: The New Biology of Machines, Social Systems, and the Economic World New Rules for the New Economy: 10 Radical Strategies for a Connected World Asia Grace WHAT TECHNOLOGY WANTS KEVIN KELLY VIKING VIKING Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A. Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephen's Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi - 110 017, India Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England First published in 2010 by Viking Penguin, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. 13579 10 8642 Copyright © Kevin Kelly, 2010 All rights reserved LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA Kelly, Kevin, 1952- What technology wants / Kevin Kelly. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-670-02215-1 1. Technology'—Social aspects. 2. Technology and civilization. I. Title. T14.5.K45 2010 303.48'3—dc22 2010013915 Printed in the United States of America Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book. -

Depression Resource List

Perinatal Mood Disorders Resource List: Many books can be ordered through the PSI website http://www.postpartum.net using Amazon.com. Many of those books are sold below list price, and a portion of those proceeds are donated to the upkeep of the PSI website. Visit the PSI website, choose to visit the PSI Postpartum Bookstore & Video Center and double click on the title of the book that you wish to buy. Books 1. The Journey to Parenthood: Myths, Reality, and What Really Matters 2007 by Diana Lynn Barnes and Leigh Balber. Radcliffe Publishing. 2. Postpartum Mood and Anxiety Disorders: A Clinician’s Guide (2006), Cheryl T. Beck, and Jeanne Watson Driscoll, Published by Jones and Bartlett Publishers, Sadbury, MA. 3. Beyond The Blues, A Guide to Understanding and Treating Prenatal and Postpartum Depression (2003) by Shoshana Bennett, PhD and Pec Indman, EdD. Moodswings Press, 1050 Windsor St., San Jose, CA 95129, 408-252-5552, or toll free 888-HUG-MOMS. www.beyondtheblues.com. Bulk rates available. 4. Postpartum Depression for Dummies 2007 by Shoshana Bennett (Author), Mary Jo Cody (Foreward). For Dummies. 5. Laughter and Tears: The Emotional Life of New Mothers 1997 by Elisabeth Bing and Libby Coleman. 6. The Cradle Will Fall 1996 by Carl Burak and Michele Remington. 7. Mood and Anxiety Disorders During Pregnancy and Postpartum (2005), edited by Lee S. Cohen, M.D. and Ruta M. Nonacs, M.D., Ph.D., published by American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc., Washington, DC. 8. Perinatal Psychiatry: Use and Misuse of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (1994) by John Cox, M.D., and Jeni Holden. -

Books Located in the National Press Club Archives

Books Located in the National Press Club Archives Abbot, Waldo. Handbook of Broadcasting: How to Broadcast Effectively. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc., 1937. Call number: PN1991.5.A2 1937 Alexander, Holmes. How to Read the Federalist. Boston, MA: Western Islands Publishers, 1961. Call number: JK155.A4 Allen, Charles Laurel. Country Journalism. New York: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1928. Alsop, Joseph and Stewart Alsop. The Reporter’s Trade. New York: Reynal & Company, 1958. Call number: E741.A67 Alsop, Joseph and Catledge, Turner. The 168 Days. New York: Doubleday, Duran & Co., Inc, 1938. Ames, Mary Clemmer. Ten Years in Washington: Life and Scenes in the National Capital as a Woman Sees Them. Hartford, CT: A. D. Worthington & Co. Publishers, 1875 Call number: F198.A512 Andrews, Bert. A Tragedy of History: A Journalist’s Confidential Role in the Hiss-Chambers Case. Washington, DC: Robert Luce, 1962. Anthony, Joseph and Woodman Morrison, eds. Best News Stories of 1924. Boston, MA: Small, Maynard, & Co. Publishers, 1925. Atwood, Albert (ed.), Prepared by Hershman, Robert R. & Stafford, Edward T. Growing with Washington: The Story of Our First Hundred Years. Washington, D.C.: Judd & Detweiler, Inc., 1948. Baillie, Hugh. High Tension. New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1959. Call number: PN4874.B24 A3 Baker, Ray Stannard. American Chronicle: The Autobiography of Ray Baker. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1945. Call number: PN4874.B25 A3 Baldwin, Hanson W. and Shepard Stone, Eds.: We Saw It Happen: The News Behind the News That’s Fit to Print. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1938. Call number: PN4867.B3 Barrett, James W. -

GOING HOME Finding Peace When Pets Die by New York Times Bestselling Author Jon Katz ~Villard Hardcover • on Sale September 27, 2011~

THE RANDOM HOUSE PUBLISHING GROUP Ballantine Books . Bantam Books . Delacorte Press . Dell . Delta . Del Rey . ESPN Books . One World . Spectra . Villard Publicity Contact: Ashley Gratz-Collier [email protected], 212-940-7876 PRAISE FOR NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLING AUTHOR JON KATZ “With wisdom and grace, Katz unlocks the canine soul and the complicated wonders that lie within and offers powerful insights to anyone who has ever struggled with, and loved, a troubled animal.” —John Grogan, author of Marley & Me “Katz’s world—of animals and humans and their combined generosity of spirit—is a place you’re glad you’ve been.” —The Boston Globe “Katz proves himself a Thoreau for modern times as he ponders the relationships between man and animals, humanity and nature.”—Fort Worth Star-Telegram “I toss a lifetime award of three liver snaps to Jon Katz.” —Maureen Corrigan, National Public Radio’s Fresh Air GOING HOME Finding Peace When Pets Die by New York Times bestselling author Jon Katz ~Villard Hardcover • On Sale September 27, 2011~ In Soul of a Dog, Izzy & Lenore, A Good Dog, and other acclaimed works, New York Times bestselling author and animal advocate Jon Katz has written meaningfully about the cherished bond between humans and animals—especially our intense connection to our pets. Now, in GOING HOME: Finding Peace When Pets Die (Villard Hardcover; On Sale September 27, 2011), Katz addresses the difficult but necessary topic of saying goodbye to a devoted companion, and offers comfort, wisdom, and a way forward from sorrow to acceptance. -over- When Jon Katz first brought Orson home, he couldn’t predict how this boisterous border collie would change his life, most notably by inspiring him to buy Bedlam Farm. -

New Non-Fiction Books

Zimmerman Library Jan-June 2017 New Non-Fiction Books Books are listed in Dewey GENERALITIES Decimal order. 000 Generalities Kavanaugh, Beatrice. Computing and the 100 Philosophy & Psychology internet. Broomall, Pa.: Mason Crest, [2017]. 200 Religion "Since it became widely available for public use 300 Social Sciences in the early 1990s, the Internet has proven to be amazingly useful for facilitating communication, 400 Language distributing information, and sharing 500 Science knowledge. Human society has already been 600 Health & Medicine changed by the Internet and as new technologies 700 Arts develop, even more opportunities will be 800 Literature available to people online. However, some 900 History & Geography people have concerns about technology and 920 Biographies privacy, the availability of new technology to Professional Reading everyone, and whether information shown on the web might . influence people or cultures in a negative way. This book will look at the role that the Internet and computer technologies play in society, and consider some of the questions that are raised by its development"--Amazon. com. 004 KAV Gonzales, Andrea. Girl code: gaming, going viral, and getting it done. 1st ed. New York, NY: Harper, an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers, [2017]. The authors, who met at a summer 1 computer programming camp for girls, share Crysdale, Joy, 1952-. Fearless female journalists. their knowledge of gaming, programming, and Toronto, ON: Second Story Press, c2010. the tech industry, and provide advice on getting Profiles ten female journalists who have taken into the field of computer programming. 005. 1 risks to report news and succeed in the field, GON including Mary Ann Shadd Cary, Nellie Bly, Doris Anderson, Farida Nekzad, Thembi O'Neil, Cathy. -

Sharon Propson, 212-782-9008/ [email protected]

THE RANDOM HOUSE PUBLISHING GROUP Ballantine Books . Bantam Books . Delacorte Press . Dell . Delta . Del Rey . ESPN Books . One World . Spectra . Villard Contact: Sharon Propson, 212-782-9008/ [email protected] The highly-anticipated new Mary Russell & Sherlock Holmes installment! “THE GOD OF THE HIVE is mesmerizing--another wonderful novel etched by the hand of a master storyteller. No reader who opens this one will be disappointed.” --Michael Connelly THE GOD OF THE HIVE By New York Times and Edgar Award-winning author Laurie R. King To be published as a Bantam Books Hardcover on April 27, 2010 Praise for Laurie R. King’s Mary Russell/ Sherlock Holmes series: “The great marvel of Laurie King’s [Mary Russell] series is that she’s managed to preserve the integrity of Holmes’s character and yet somehow conjure up a woman astute, edgy, and compelling enough to be the partner of his mind as well as his heart.” —The Washington Post Book World “Audacious… Mary Russell is never less than fascinating company.” —Los Angeles Times “Good historical fiction is as close as we’ll ever get to time travel, and historical fiction doesn’t get any better than this.” —The Denver Post “Of the many fine writers currently adding to the canon of stories about [Holmes], the nimblest is Laurie R. King….Splendid fun.” —The Seattle Times “Excellent….King never forgets the true spirit of Conan Doyle.” —Chicago Tribune Critics have applauded New York Times bestselling, Edgar Award-winning author Laurie R. King’s lively and intelligent recasting of the iconic character of Sherlock Holmes with Mary Russell, a wife and partner of equal wit and cleverness, as “the most successful recreation of the famous inhabitant of 221B Baker Street ever attempted” (Houston Chronicle). -

Judi Neal, Ph.D

Faith and Spirituality in the Workplace Bibliography Compiled by Judi Neal, Ph.D. Director, Tyson Center for Faith and Spirituality in the Workplace Abdullah, Sharif. 1999. Creating a world that works for all. San Francisco: Berrett- Koehler. Aburdene, Patricia. 2005. Megatrends 2010: The rise of conscious capitalism, Charlottsville, VA: Hampton Roads Publishing. Adams, John D. (ed.) 1984. Transforming work: A collection of organization transformation readings, Alexandria, VA: Miles River Press. Adams, John D. (ed.) 1986. Transforming leadership: From vision to results, Alexandria, VA: Miles River Press. Adams, John. 2006. Building a Sustainable World: A Challenging OD Opportunity in The NTL Handbook of Organizational Development and Change. San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer. Adams, Scott. 1996. The Dilbert principle. New York: HarperBusiness. Agor, W.H. (ed.) 1989. Intuition in organizations. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Albert, Susan. 1993. Escaping the career culture, in Michael Ray and Alan Rinzler (eds.), The new paradigm in business: Emerging strategies for leadership and organizational change, NY: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Perigee, 43-49. Albion , Mark. Making a life, Making a living: Reclaiming your purpose and passion in business and in life. Warner. Created by Judith Neal 1 Tyson Center for Faith and Spirituality in the Workplace Sam M. Walton College of Business, University of Arkansas Alderfer, C. P. 1972. Existence, Relatedness, and Growth: Human Needs in Organizational Settings. New York, NY: Free Press. Alderson, Wayne & Nancy Alderson McDonnell. 1994. Theory R management: How to utilize the value of the person leadership principles of love, dignity, and respect, Nashville: Thomas Nelson. Allen, Marc. 1995. Visionary Business: An entrepreneur's guide to success. -

Random House, Inc. Booth #52 & 53 M O C

RANDOM HOUSE, INC. BOOTHS # 52 & 53 www.commonreads.com One family’s extraordinary A remarkable biography of The amazing story of the first One name and two fates From master storyteller Erik Larson, courage and survival the writer Montaigne, and his “immortal” human cells —an inspiring story of a vivid portrait of Berlin during the in the face of repression. relevance today. grown in culture. tragedy and hope. first years of Hitler’s reign. Random House, Inc. is proud to exhibit at this year’s Annual Conference on The First-Year Experience® “One of the most intriguing An inspiring book that brings novels you’ll likely read.” together two dissimilar lives. Please visit Booths #52 & 53 to browse our —Library Journal wide variety of fiction and non-fiction on topics ranging from an appreciation of diversity to an exploration of personal values to an examination of life’s issues and current events. With so many unique and varied Random House, Inc. Booth #52 & 53 & #52 Booth Inc. House, Random titles available, you will be sure to find the right title for your program! A sweeping portrait of Anita Hill’s new book on gender, contemporary Africa evoking a race, and the importance of home. world where adults fear children. “ . [A] powerful journalistic window “ . [A]n elegant and powerful A graphic non-fiction account of “ . [A] blockbuster groundbreaking A novel set during one of the most into the obstacles faced by many.” plea for introversion.” a family’s survival and escape heartbreaking symphony of a novel.” conflicted and volatile times in –MacArthur Foundation citation —Brian R. -

Download 2020 Iread Resource Guide Home Edition

iREADiREAD HOMEHOME EDITIONEDITION 20202020 2021iREAD Summer Reading The theme for iREAD’s 2021 summer reading program is Reading Colors Your World. The broad motif of “colors” provides a context for exploring humanity, nature, culture, and science, as well as developing programming that demonstrates how libraries and reading can expand your world through kindness, growth, and community. Readers will be encouraged to be creative, try new things, explore art, and find beauty in diversity. Illustrations and posters tell the story: Read a book and color your world! Artwork ©2019 Hervé Tullet [www.sayzoop.com] for iREAD®. iREAD® (Illinois Reading Enrichment and Development) is an annual project of the Illinois Library Association, the voice for Illinois libraries and the millions who depend on them. It provides leadership for the development, promotion, and improvement of library services in Illinois and for the library community in order to enhance learning and ensure access to information for all. The goal of this reading program is to instill the enjoyment of reading and to promote reading as a lifelong pastime. Dig Deeper: Read, Investigate, Discover; Reading Colors Your World and all associated materials ©2019 Illinois Library Association. DIG DEEPER: READ, INVESTIGATE, DISCOVER 2020 iREAD® Resource Guide Portia Latalladi 2020 iREAD® Chair Alexandra Annen 2021 iREAD® Chair Becca Boland 2022 iREAD® Chair Brandi Smits 2020 iREAD® Ambassador Sarah Rice Resource Guide Coordinator David Roberts Pre-K Program Illustrator Rafael López Children’s Program Illustrator Alleanna Harris Young Adult Program Illustrator Jingo de la Rosa Adult Program Program Illustrator Diane Foote Executive Director, Illinois Library Association A PRODUCTION OF THE ILLINOIS LIBRARY ASSOCIATION Table of Contents Table of Contents 1. -

100 Families That Changed the World

JOSEP TÀPIES • ELENA SAN ROMÁN • ÁGUEDA GIL LÓPEZ 100 FAMILIES THAT CHANGED THE WORLD Family Businesses and Industrialization “If there is one quality that centenarian firms have in common, it is that they have known how to adapt to the many circumstances and challenges they have been faced with. Family businesses are usua- lly managed with a long-term vision, and there can be no doubt that the companies featured in this book provide a clear example of how to achieve this.” José María Serra, chairman of Grupo Catalana Occidente “This book is an effective tool for better understanding the manage- rial and industrial development of family businesses. This is undoub- tedly an objective approach that allows the reader to learn about the key factors that, in each case, have been fundamental to the suc- cess of centenarian companies. Moreover, it is a work of study and analysis that reveals the best practices of each company in an effort to keep its activity going throughout the years.” Tomás Osborne, chairman of the Osborne Group */3%04±0)%3s%,%.!3!.2/-£.s£'5%$!'),,0%: 'BNJMJFT5IBU$IBOHFEUIF8PSME 'BNJMZ#VTJOFTTFTBOE*OEVTUSJBMJ[BUJPO 100 Families That Changed the World Family Businesses and Industrialization Josep Tàpies, Elena San Román, Águeda Gil All rights reserved. Total or partial reproduction of this work by any means or process, including photocopying and computer processing, and distribution of copies released by rental or public lending is strictly prohibited without written permission from the copyright holders, under penalty of law. First edition: May 2014 © Josep Tàpies, Elena San Román, Águeda Gil, 2014 © Jesús Serra Foundation © Ediciones Universidad de Navarra, S.A. -

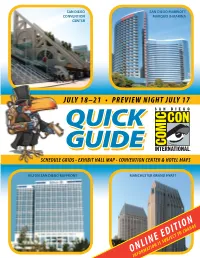

Quick Guide Is Online

SAN DIEGO SAN DIEGO MARRIOTT CONVENTION MARQUIS & MARINA CENTER JULY 18–21 • PREVIEW NIGHT JULY 17 QUICKQUICK GUIDEGUIDE SCHEDULE GRIDS • EXHIBIT HALL MAP • CONVENTION CENTER & HOTEL MAPS HILTON SAN DIEGO BAYFRONT MANCHESTER GRAND HYATT ONLINE EDITION INFORMATION IS SUBJECT TO CHANGE MAPu HOTELS AND SHUTTLE STOPS MAP 1 28 10 24 47 48 33 2 4 42 34 16 20 21 9 59 3 50 56 31 14 38 58 52 6 54 53 11 LYCEUM 57 THEATER 1 19 40 41 THANK YOU TO OUR GENEROUS SHUTTLE 36 30 SPONSOR FOR COMIC-CON 2013: 32 38 43 44 45 THANK YOU TO OUR GENEROUS SHUTTLE SPONSOR OF COMIC‐CON 2013 26 23 60 37 51 61 25 46 18 49 55 27 35 8 13 22 5 17 15 7 12 Shuttle Information ©2013 S�E�A�T Planners Incorporated® Subject to change ℡619‐921‐0173 www.seatplanners.com and traffic conditions MAP KEY • MAP #, LOCATION, ROUTE COLOR 1. Andaz San Diego GREEN 18. DoubleTree San Diego Mission Valley PURPLE 35. La Quinta Inn Mission Valley PURPLE 50. Sheraton Suites San Diego Symphony Hall GREEN 2. Bay Club Hotel and Marina TEALl 19. Embassy Suites San Diego Bay PINK 36. Manchester Grand Hyatt PINK 51. uTailgate–MTS Parking Lot ORANGE 3. Best Western Bayside Inn GREEN 20. Four Points by Sheraton SD Downtown GREEN 37. uOmni San Diego Hotel ORANGE 52. The Sofia Hotel BLUE 4. Best Western Island Palms Hotel and Marina TEAL 21. Hampton Inn San Diego Downtown PINK 38. One America Plaza | Amtrak BLUE 53. The US Grant San Diego BLUE 5. -

Simon's Rock Authors

Simon’s Rock Authors - Bard College at Simon’s Rock Alumni Library Abbas, Asma Liberalism and human suffering : materialist reflections on politics, ethics, and aesthetics / Asma FAC Abbas. New York : Palgrave Macmillan, 2010 Stacks -- Call#: JC574 .A274 2010 Abbott, Alana Joli Departure / [Alana Abbott] ALUM McComb, MS : White Silver Pub, 2006 Stacks -- Call#: PS3601 .B353 D42 2006 Adler Beléndez, Ekiwah The coyote's trace : a collection of poems / Ekiwah Adler Beléndez ALUM Amatlán, Morelos, México : Ediciones del Arkan, 2006 Stacks -- Call#: PQ7298.1 .D54 C66 2006 Adler Beléndez, Ekiwah Palabras inagotables : [a collection of poems] / Ekiwah Adler Beléndez ALUM Jiutepec, México : ConNow/Otr@as, 2001 Stacks -- Call#: PQ7298.1 .D54 P35 2001 Adler Beléndez, Ekiwah Soy : poemas y cuentos / Ekiwah Adler Beléndez ALUM Amatlán, Morelos, México : Ediciones del Arkan, 2001 Stacks -- Call#: PQ7298.1 .D54 S69 2001 Adler Beléndez, Ekiwah Weaver : a collection of poems / Ekiwah Adler Beléndez ALUM Amatlán, Morelos, México : Ediciones del Arkan, 2003 Stacks -- Call#: PQ7298.1.D4 W43 2003 Alford, Henry Big kiss : one actor's desperate attempt to claw his way to the top / Henry Alford ALUM New York : Villard, c2000 Stacks -- Call#: PN2055 .A54 2000 Alford, Henry How to live : a search for wisdom from old people / Henry Alford ALUM New York : Twelve, 2009 Stacks -- Call#: HQ1061 .A52 2009 Alford, Henry Municipal bondage / Henry Alford ALUM New York : Random House, c1993 Stacks -- Call#: PN6162 .A365 1993 Alford, Henry Would it kill you to stop doing