Andrew Christopher Tracy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Killam Trusts Annual Report 2007

THE KILLAM TRUSTS ANNUAL REPORT 2007 Sarah Pace, BA (Hons) Administrative Officer to the Killam Trusts 1391 Seymour Street Halifax, NS B3H 3M6 T: (902) 494-1329 F:(902) 494-6562 [email protected] Published by the Trustees of the Killam Trusts www.killamtrusts.ca THE KILLAM TRUSTS ANNUAL REPORT 2007 Sarah Pace, BA (Hons) Administrative Officer to the Killam Trusts 1391 Seymour Street Halifax, NS B3H 3M6 T: (902) 494-1329 F:(902) 494-6562 [email protected] Published by the Trustees of the Killam Trusts www.killamtrusts.ca 2007 Annual Report of The Killam Trustees 2007 Annual Report of The Killam Trustees With infinite sadness, we record that our beloved fellow Trustee, W. Robert Wyman, passed away in June. A few weeks before his death, Dr. Indira Samarasekera, President and Vice Chancellor of the University of Alberta and Dr. Mark Dale, Dean of the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research, journeyed to Vancouver to con- fer an honourary LLD degree on Bob at his home. At the U of A Special Convocation held in Edmonton later in the year, Bob’s wife Donna and daughter Robin told us of his deep satisfaction at having received this honour from the university of his birthplace and childhood, the city of Edmonton. Please see page 17 for a more detailed tribute to this remarkable Canadian and his inestimable contribution to higher education in Canada. Moncton, New Brunswick is a medium-sized but up and coming city. Its recent growth rests on three promising features: its loca- tion at the transportation hub of the Maritime Provinces; its highly entrepreneurial citizenry; and a thriving cultural life. -

Drew Hayden Taylor, Native Canadian Playwright in His Times

BRIDGING THE GAP: DREW HAYDEN TAYLOR, NATIVE CANADIAN PLAYWRIGHT IN HIS TIMES Dale J. Young A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2005 Committee: Dr. Ronald E. Shields, Advisor Dr. Lynda Dixon Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Jonathan Chambers Bradford Clark © 2005 Dale Joseph Young All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Ronald E. Shields, Advisor In his relatively short career, Drew Hayden Taylor has amassed a significant level of popular and critical success, becoming the most widely produced Native playwright in the world. Despite nearly twenty years of successful works for the theatre, little extended academic discussion has emerged to contextualize Taylor’s work and career. This dissertation addresses this gap by focusing on Drew Hayden Taylor as a writer whose theatrical work strives to bridge the distance between Natives and Non-Natives. Taylor does so in part by humorously demystifying the perceptions of Native people. Taylor’s approaches to humor and demystification reflect his own approaches to cultural identity and his expressions of that identity. Initially this dissertation will focus briefly upon historical elements which served to silence Native peoples while initiating and enforcing the gap of misunderstanding between Natives and non-Natives. Following this discussion, this dissertation examines significant moments which have shaped the re-emergence of the Native voice and encouraged the formation of the Contemporary Native Theatre in Canada. Finally, this dissertation will analyze Taylor’s methodology of humorous demystification of Native peoples and stories on the stage. -

CANADA's ROYAL WINNIPEG BALLET Thu, Oct 20, 7:30 Pm Carlson Family Stage

2016 // 17 SEASON Northrop Presents CANADA'S ROYAL WINNIPEG BALLET Thu, Oct 20, 7:30 pm Carlson Family Stage DRACULA Dear Northrop Dance Lovers, Northrop at the University of Minnesota Presents It’s great to welcome Canada’s Royal Winnipeg Ballet back to Northrop! We presented their WONDERLAND at the Orpheum in 2011, but they last appeared on this stage in 2009 with their sensational Moulin Rouge. Northrop was a CANADA'S ROYAL very different venue then, and the dancers are delighting in the transformation of this historic space. The work that Royal Winnipeg brings us tonight boasts WINNIPEG BALLET quite a history as well. When it first came out in 1897, Bram th Stoker’s novel was popular enough, but it was the early 20 Under the distinguished Patronage of His Excellency century film versions that really caused its popularity to The Right Honourable David Johnston, C.C., C.M.M., C.O.M., C.D. skyrocket. The play DRACULA appeared in London in 1924 Governor General of Canada and had a successful three-year tour, and then the American version opened in New York City in 1927 and grossed over $2 Founders, GWENETH LLOYD & BETTY FARRALLY million in its first year (that’s in 1927 dollars, and 1927 ticket Artistic Director Emeritus, ARNOLD SPOHR, C.C., O.M. prices). Founding Director, School Professional Division, DAVID MORONI, C.M. Founding Director, School Recreational Division, JEAN MACKENZIE Christine Tschida. Photo by Tim Rummelhoff. So, what is it about this vampire tale that still evokes dread and horror, but most of all, fascination? That’s a subject Artistic Director currently being explored by our first University Honors Program-coordinated interdisciplinary, outside- ANDRÉ LEWIS the-classroom Honors Experience: Dracula in Multimedia. -

Theatre and Transformation in Contemporary Canada

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by YorkSpace Theatre and Transformation in Contemporary Canada Robert Wallace The John P. Robarts Professor of Canadian Studies THIRTEENTH ANNUAL ROBARTS LECTURE 15 MARCH 1999 York University, Toronto, Ontario Robert Wallace is Professor of English and Coordinator of Drama Studies at Glendon College, York University in Toronto, where he has taught for over 30 years. During the 1970s, Prof. Wallace wrote five stage plays, one of which, No Deposit, No Return, was produced off- Broadway in 1975. During this time, he began writing theatre criticism and commentary for a range of newspapers, magazines and academic journals, which he continues to do today. During the 1980s, Prof. Wallace simultaneously edited Canadian Theatre Review and developed an ambitious programme of play publishing for Coach House Press. During the 1980s, Prof. Wallace also contributed commentary and reviews to CBC radio programs including Stereo Morning, State of the Arts, The Arts Tonight and Two New Hours; for CBC-Ideas, he wrote and produced 10 feature documentaries about 20th century performance. Robert Wallace is a recipient of numerous grants and awards including a Canada Council Aid to Artists Grant and a MacLean-Hunter Fellowship in arts journalism. His books include The Work: Conversations with English-Canadian Playwrights (1982, co-written with Cynthia Zimmerman), Quebec Voices (1986), Producing Marginality: Theatre 7 and Criticism in Canada (1990) and Making, Out: Plays by Gay Men (1992). As the Robarts Chair in Canadian Studies at York (1998-99), Prof. Wallace organized and hosted a series of public events titled “Theatre and Trans/formation in Canadian Culture(s)” that united theatre artists, academics and students in lively discussions that informed his ongoing research in the cultural formations of theatre in Canada. -

Artsnews SERVING the ARTS in the FREDERICTON REGION September 22, 2016 Volume 17, Issue 37

ARTSnews SERVING THE ARTS IN THE FREDERICTON REGION September 22, 2016 Volume 17, Issue 37 In this issue *Click the “Back to top” link after each notice to return to “In This Issue”. Upcoming Events 1. Centre communautaire Sainte-Anne’s launches the 2016-17 Season with Cy & Christian KIT Goguen Sept 22 2. The UNB Art Centre presents The Next Chapter & The Stained Glass Windows of Memorial Hall Sept 23 3. Marimba Duo Taktus perform Glass Houses for Marimba Sept 22 4. Kenny James and Carla Bonnell at Grimross Brewing Co. Sept 23 5. Public Lecture: Goddesses, Whores, Vampyres & Archaeologists: Uncovering Ancient Mytilene Sept 23 6. Gardenfest Music Festival Sept 24 7. Spotlight Series presents Joe Ink at The Playhouse Sept 24 8. The Motorleague & Brother at The Capital Sept 24 9. TNB Open Space Theatre Tours Available Sept 25 10. iTrombini Chamber Music Concert at Brunswick Street Baptist Church Sept 25 11. Monday Night Film Series presents The Man Who Knew Infinity (Sept 26) & Sunset Song (Oct 3) 12. Registration Continues for the Fredericton Choral Society Sept 27 13. Potted Potter at The Playhouse Sept 27 14. Music on the Hill presents Dissonant Grooves at Memorial Hall Sept 28 15. Marty Haggard at The Playhouse Sept 29 16. Stand-up Comic Korine Côté at Centre Communautaire Sainte-Anne Sept 29 17. Music Runs Through It presents Scott Cook at Corked Wine Bar Sept 29 18. New Brunswick Media Co-Op Annual General Meeting Sept 29 19. Tenor Marcel d’Entremont at Christ Church Parish Church Sept 30 20. -

Drennan Barbara Phd 1995.Pdf

PERFORMED NEGOTIATIONS: The Historical Significance of the Second Wave Alternate Theatre in English Canada and Its Relationship to the Popular Tradition by Barbara Drennan B.F^., University of Windsor, 1973 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Theatre We accept this dissertation as conforming to the required standard Michael R. Booth, Supervisor (Department of Theatre) Juliapa M. Saxton (Department of Theatre) Murray D. Edwards (Department of Theatre) Stephen A.C. Scobie (Department of English) Dr. Malcolm Page, External Examiner (Department of English, Simon Fraser University) © Barbara Drennan, 1995 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopying or other means, without the permission of the author. Supervisor: Michael R. Booth ABSTRACT This doctoral project began in the early 1980s when 1 became involved in making a community theatre event on Salt Spring Island with a group of artists accomplished in disciplines other than theatre. The production was marked by an oiientation toward creating stage images rather than a literary text and by the playful exploitation of theatricality. This experiment in theatrical performance challenged my received ideas about theatre and drama. As a result of this experience, I began to see differences in original, small-venue productions which were considered part of the English-Canadian alternate theatre scene. I deter mined that the practitioners who created these events could be considered a second generation to the Alternate Theatre Movement of the 70s and settled on identifying their practice as Second Wave. -

GROWING PAINS Toronto Theatre in the Igjo's

GROWING PAINS Toronto Theatre in the igjo's Robert Wallace (for Brenda Donohue) "The geography of the situation becomes so dense, so rich with possible paths, that the instinctive sense of direction fails; and questions of destination are rapidly replaced by the concerns of Survival." MARTIN KINGH "In this country there's an appetite to put buildings up, to equate culture with cupolas and glass palaces." — PAUL BETTIS 1LN AN ARTICLE PUBLISHED in Canadian Theatre Review, no. 2i, in 1979, Ken Gass, founder of Toronto's Factory Theatre Lab, concludes: Toronto may be a bustling, chic metropolis with abundant resources and an active theatre industry, but it is also thoroughly conservative and not the most conducive environment for serious theatre work. Gass's opinion of Toronto theatre at the end of the seventies is not as important as the fact he takes for granted: in just ten years, an "active theatre industry" has emerged where little was before. The 1979/80 edition of the Canadian Theatre Checklist contains over fifty listings of theatre buildings and companies in the Toronto area, few of which existed in 1969.1 City Nights, a weekly entertainment guide circulated throughout the city, offers a constantly changing roster of theatri- cal events. At least one review of a new play, cabaret act, or theatre piece can be found in the entertainment sections of Toronto's daily newspapers. Commercial ticket agencies with offices in the suburbs are thriving while pre-curtain box-office queues are customary at many downtown theatres. Dinner theatres, cabarets and revue houses flourish across the city, not to mention the taverns, bars and pubs featuring a wide variety of acts and complementing the legitimate theatres. -

Box # # of Items in Folder Name of Organization

Box # of Name of Organization (note: names that are underlined are filed by the underlined word in alphabetical order) Location # Items in Folder 1 1 Feike Asma. Organ recital. Toronto Toronto 1 ARS NOVA presents Theatre of Early Music presents "Star of Wonder" A Christmas Concert. Knox Presbyterian Church, Ottawa Ottawa. 1 ARS Omnia with Contemporary Music Projects presents The Inspiration of Greece and China. A trans-cultural Toronto contemporary music event. Kings College Circle, University of Toronto. 1 2 ARS Organi. Montreal 1 L'ARMUQ Quebec 1 1 A Benefit Concert for Women's College Hospital. John Arpin, [Pianist.]. Women's College Hospital 75th Anniversary, Toronto 1911-1986. Roy Thomson Hall, Toronto. 1 1 A Space - Toronto. Toronto 1 L'Academie Commerciale Catholique de Montreal. Montreal 1 1 L'Academie Des Lettres Et Des Sciences Humaine de la Society Royal Du Canada. [Ottawa?] 1 1 Academy of Dance. [Brantford, Ontario?] 2 Acadia University. Wolfville, Nova Scotia. Nova Scotia 1 2 ACME Theatre Company. Toronto 1 2 Acting Company. Toronto. Toronto 1 1 The Actors Workshop. Toronto. Toronto 1 1 Acustica International Montreal. Montreal 1 1 John Adams. New Music for synthesizers, solo bass and grand pianos by John Adams & Chan Ka Nin. Premiere Dance Toronto Theatre. New Music Concert. [Toronto.] 1 1 Adelaide Court Theatre. Toronto. Toronto 1 1 The Aeolian Town Hall. The London School Of Church Music. A Concert to honour the Silver Jubilee of Her Majesty London, Ontario Queen Elizabeth II. 1 Aetna Canada Young People's Concerts. Toronto. Toronto 1 2 Afternoon Concert Series. The Women's Musical Club of Toronto. -

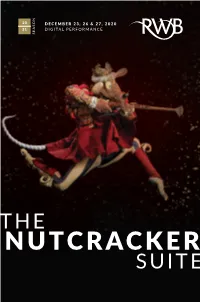

NUTCRACKER SUITE Canada's Royal Winnipeg Ballet Tableau

20 DECEMBER 23, 26 & 27, 2020 21 DIGITAL PERFORMANCE THE NUTCRACKER SUITE Canada's Royal Winnipeg Ballet Tableau UNDER THE DISTINGUISHED PATRONAGE OF HER EXCELLENCY THE RIGHT HONOURABLE Julie Payette, C.C., C.M.M., C.O.M., C.Q., C.D., Governor General of Canada FOUNDERS Gweneth Lloyd & Betty Farrally ARTISTIC DIRECTOR EMERITUS Arnold Spohr, C.C., O.M. FOUNDING DIRECTOR, SCHOOL RECREATIONAL DIVISION Jean Mackenzie FOUNDING DIRECTOR, SCHOOL PROFESSIONAL DIVISION David Moroni, C.M., O.M., D.Litt, (h.c.) ARTISTIC DIRECTOR & CEO André Lewis ARTISTS Yayoi Ban, Elizabeth Lamont, Chenxin Liu, Alanna McAdie, Yosuke Mino, Yue Shi, Katie Bonnell, Stephan Azulay, Liam Caines, Ryan Vetter, Jenna Burns, Jaimi Deleau, Elena Dobrowna, Katie Simpson, Sarah Joan Smith, Amanda Solheim, Joshua Hidson, Peter Lancksweerdt, Michel Lavoie, Parker Long, Liam Saito Tymin Keown, Emilie Lewis, and Brooke Thomas ASSOCIATE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Tara Birtwhistle PRINCIPAL CONDUCTOR Julian Pellicano SENIOR BALLET MASTER Johnny W. Chang BALLET MASTERS Caroline Gruber, Vanessa Léonard, Jaime Vargas SCHOOL DIRECTOR Stéphane Léonard RECREATIONAL DIVISION PRINCIPAL Nicole Kepp PROFESSIONAL DIVISION PRINCIPAL Suzanne André TEACHER TRAINING PROGRAM DIRECTOR Johanne Gingras STAGE MANAGER Candace Jacobson ASSISTANT STAGE MANAGER Ryan Bjornson Land and Water Acknowledgment We are grateful to practice our art on Treaty One land, the traditional territory of the Anishinaabeg, Cree, Oji-Cree, Dakota, and Dene peoples, and the homeland of the Métis Nation. We acknowledge that our water is sourced from Shoal Lake 40 First Nation. We stand with the indigenous community and commit to build an ongoing process of reconciliation and collaboration. ISSUE NO. 217 | ISSN: 1495-9291 Cover: Yue Shi, Photo by David Cooper We are pleased to receive your feedback, comments and The Royal Winnipeg Ballet is a chartered non-profit corporation questions. -

Box File No. Title Location Aca

BOX FILE NO. TITLE LOCATION A.C.A. Newsletter. Alberta Composers' Association Newsletter. Alberta A.S.O. Atlantic Symphony Orchestra. Newfoundland, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia …. Nova Scotia …. [Atlantic Provinces] A Benefit Concert for Women's College Hospital. John Arpin, [Pianist.]. Women's College Hospital 75th Anniversary, Toronto. 1911-1986. Roy Thomson Hall, Toronto. 1 1 A Space - Toronto. Toronto 1 2 L'Acadamie Des Lettres Et Des Sciences Humaine de la Society Royal Du Canada. [Ottawa?] 1 3 Academy of Dance. [Brantford, Ontario?] Acadia University. Wolfville, Nova Scotia. Nova Scotia 1 4 ACME Theatre Company. Toronto Acting Company. Toronto. Toronto 1 5 The Actors Workshop. Toronto. Toronto John Adams. New Music for synthesizers, solo bass and grand pianos by John Adams & Chan Ka Nin. Premiere Dance Toronto. Theatre. New Music Concert. [Toronto.] 1 6 Adelaide Court Theatre. Toronto. Toronto 1 7 The Aeolian Town Hall. The London School Of Church Music. A Concert to honour the Silver Jubilee of Her Majesty London, Ontario Queen Elizabeth II. 1 8 Aetna Canada Young People's Concerts. Toronto. Toronto African Theatre Ensemble. Toronto 1 9 AfriCanadian Playwrights Festival. Toronto. Toronto 1 10 Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Kingston. Kingston Aid to Artists. The Canada Council, 1978-79. Ottawa. Ottawa Air Command Band. Winnipeg 1 11 Alberta College. Alberta The Alberta Music Conference. Banff School of Fine Arts. Alberta 1 12 The Aldeburgh Connection. Concert Society. Toronto. Toronto Lenore Alford, orgue. Conseil Des Arts et Des Lettres Du Quebec. Quebec 1 13 Algoma Fall Festival. Saulte Ste. Marie, Ontario. Saulte Ste. Marie, Ontario Alianak Theatre. -

Various Locations Canada Abilities Centre Canada Aboriginal Human

Scotiabank - 2010 philanthropic donations sample list Organization Name Country 4-H - various locations Canada Abilities Centre Canada Aboriginal Human Resource Development Council of Canada Canada AboutFace International Canada Abreast In A Boat Society Canada Acadia University Canada ACT Foundation Canada Adoptive Families Association of BC Canada Advancing Canadian Entrepreneurship Canada Aga Khan Foundation Canada Canada Agape Centre Canada Agricultural Society - various locations Canada Aid for AIDS United States AIDS Coalition of Nova Scotia Canada Aids Committee of London Canada AIDS Committee of Toronto (ACT) Canada AIDS P.E.I. Canada Alberta Adolescent Recovery Centre Canada Alberta Children's Hospital Foundation Canada ALE Órganos Mexico Algoma University College Canada Algonquin College Canada All Saints Cathedral School USVI Allies for Autism Foundation Canada Alma Children's Education Foundation Canada Almonte General Hospital Canada Alzheimer Society - various locations Canada Amadeus Steen Foundation Canada Amazing Grace Foundation for handicapped children Antigua American Red Cross USVI Amica House Trinidad & Tobago Anaphylaxis Canada Canada Anishinabek Nation Seven Generations Charity Canada Aquí nadie se rinde Mexico Army Cadet League of Canada - various locations Canada Art Gallery of Ontario Canada Art of Time Ensemble Canada Arthritis Society - various locations Canada Arts for Children & Youth Canada Asile Communale Haiti Asociación ASAYNE Costa Rica Asociación de la Ciencia y la Educación Moral A.C.E.M Costa Rica -

Michel Tremblay's Albertine En Cinq Temps: a Tale of Two Translations

University of Alberta Michel Tremblay’s Albertine en cinq temps : A Tale of Two Translations Andrea Marie Kennedy A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Translation Studies Modern Languages and Cultural Studies ©Andrea Kennedy Fall 2011 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Dedication This thesis is dedicated to my father Murray Kennedy who always stood behind me and knew I would succeed. Without his constant encouragement and support I would not have made it through this process. Abstract This thesis compares two translations done of the play written by dramaturge Michel Tremblay entitled, Albertine en cinq temps. Using A. Berman’s critique of translation and elements of linguistic analysis, the key characterizing elements of Tremblay’s plays are identified and then used as a base for analyzing the two existing translations of this work. To conclude my thesis, I have put forth my own translation of this play.