Jane Addams' Theory of Democracy and Social Ethics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lillian Wald (1867 - 1940)

Lillian Wald (1867 - 1940) Nursing is love in action, and there is no finer manifestation of it than the care of the poor and disabled in their own homes Lillian D. Wald was a nurse, social worker, public health official, teacher, author, editor, publisher, women's rights activist, and the founder of American community nursing. Her unselfish devotion to humanity is recognized around the world and her visionary programs have been widely copied everywhere. She was born on March 10, 1867, in Cincinnati, Ohio, the third of four children born to Max and Minnie Schwartz Wald. The family moved to Rochester, New York, and Wald received her education in private schools there. Her grandparents on both sides were Jewish scholars and rabbis; one of them, grandfather Schwartz, lived with the family for several years and had a great influence on young Lillian. She was a bright student, completing high school when she was only 15. Wald decided to travel, and for six years she toured the globe and during this time she worked briefly as a newspaper reporter. In 1889, she met a young nurse who impressed Wald so much that she decided to study nursing at New York City Hospital. She graduated and, at the age of 22, entered Women's Medical College studying to become a doctor. At the same time, she volunteered to provide nursing services to the immigrants and the poor living on New York's Lower East Side. Visiting pregnant women, the elderly, and the disabled in their homes, Wald came to the conclusion that there was a crisis in need of immediate redress. -

“Happy Housewives”: Sisters in the Struggle for Women's Rights

This is a student project that received either a grand prize or an honorable mention for the Kirmser Undergraduate Research Award. “Happy Housewives”: Sisters in the Struggle for Women’s Rights Emily Wilson Date Submitted: April 24, 2016 Kirmser Award Kirmser Undergraduate Research Award – Individual Non-Freshman, honorable mention How to cite this manuscript If you make reference to this paper, use the citation: Wilson, E. (2016). “Happy Housewives”: Sisters in the Struggle for Women’s Rights. Retrieved from http://krex.ksu.edu Abstract & Keywords ““Happy Housewives”: Sisters in the Struggle for Women’s Rights” discusses social advancement from the perspective of an often unacknowledged group of people, the domestic and motherly “happy housewives”, who played a unique and unexpectedly important role in the progress of the Women’s Rights Movement in the 19th century. This paper argues that the women who prescribed to the ideology of separate spheres—that man had his place in society and woman had hers in the home—though often belittled, were essential to the progress of the Women’s Rights Movement. While outspoken suffragettes paraded the streets and outwardly protested for women’s rights, the “happy housewives” expanded women’s influence and societal distinction in subtle but significant ways that changed women’s role in the United States forever. Primary sources that support this claim include personal accounts and letters from “happy housewives”, sermons on the subject of women’s role in society, articles published in ladies’ magazines by and for the “happy housewives”, speeches, newspaper publications, cookbooks, and teachers’ guides. Keywords: Women’s Rights Movement, domestic sphere, ideology of separate spheres, women’s role, Industrial Revolution, United States Course Information School: Kansas State University Semester: Spring 2016 Course Title: Advanced Seminar in History Course Number: HIST 586 Instructor: Dr. -

Message to the Congress Transmitting a Report on Critical Infrastructure Protection March 1, 2001 Proclamation 7411—Women's

Administration of George W. Bush, 2001 / Mar. 2 385 Afghanistan and Burma Proclamation 7411—Women’s In making these determinations, I have History Month, 2001 considered the factors set forth in section 490 March 1, 2001 of the Act, based on the information con- tained in the International Narcotics Control By the President of the United States Strategy Report of 2001. Given that the per- of America formance of each of these countries has dif- A Proclamation fered, I have attached an explanatory state- In 1845, journalist and author Margaret ment for each of the countries subject to this Fuller laid out her hope for the future of determination. this Nation’s women: ‘‘We would have every You are hereby authorized and directed to arbitrary barrier thrown down. We would report this determination to the Congress im- have every path laid open to women as freely mediately and to publish it in the Federal as to men. If you ask me what offices they Register. may fill, I reply—any, I do not care what case you put; let them be sea captains, if you George W. Bush will.’’ More than 150 years later, we are closer than ever to realizing Margaret Fuller’s Message to the Congress dream. Women account for nearly half of all Transmitting a Report on Critical workers. Today, women are ‘‘captains’’ of Infrastructure Protection their own destinies, and they will continue March 1, 2001 to help shape our Nation’s future. Women hold 74 seats in the United States Congress, To the Congress of the United States: more than at any time in our country’s his- tory, and women own more than 9 million Pursuant to section 1053 of the Defense businesses employing more than 27.5 million Authorization Act of 2001 (Public Law 106– workers. -

Print Section

GROWTH AND TURMOIL, 1948-1977 Growing Tensions Content Warning: This resource addresses physical and sexual violence. Resource: Life Story: Marsha P. Johnson (1945-1992) Suggested Activities • Marsha was neither the first nor the last transwoman of color to be a victim of violence. Regardless of the true nature of her death, she was a victim of violence, including police brutality, throughout her life. Invite students to research recent activism around the extreme violence that transwomen of color continue to face. You may wish to start with a screening of The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson or a search for the Black Trans Lives Matter movement. • Much of Marsha’s life story has been pieced together through interviews featured in the documentary Pay It No Mind—The Life and Times of Marsha P. Johnson. Screen excerpts from this film so that students can hear directly from Marsha and the people in her life. • Compare the lives of Marsha P. Johnson and Christine Jorgensen, two transwomen from New York City. How did issues of race and privilege inform their experiences? • Connect Marsha’s life story to other LGBTQ individuals within WAMS, including Thomas(ine) Hall, the Public Universal Friend, Bessie Smith, Jane Addams, Pauli Murray, Christine Jorgensen, Antonia Pantoja, and Billie Jean King. • One of Marsha’s proudest moments was with Andy Warhol. Invite students to study Warhol’s portrait of Marsha and learn about the Ladies and Gentleman series through the Tate Britain’s website. • Invite students to learn more about the Stonewall Inn uprising by exploring the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project and the National Park Service websites. -

Westhoff Book for CD.Pdf (2.743Mb)

Urban Life and Urban Landscape Zane L. Miller, Series Editor Westhoff 3.indb 1 5/14/2007 12:39:31 PM Westhoff 3.indb 2 5/14/2007 12:39:31 PM A Fatal Drifting Apart Democratic Social Knowledge and Chicago Reform Laura M. Westhoff The Ohio State University Press Columbus Westhoff 3.indb 3 5/14/2007 12:39:33 PM Copyright © 2007 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Westhoff, Laura M. A fatal drifting apart : democratic social knowledge and Chicago reform / Laura M. Westhoff. — 1st. ed. p. cm. — (Urban life and urban landscape) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-1058-1 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-1058-9 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-9137-5 (cd-rom) ISBN-10: 0-8142-9137-6 (cd-rom) 1. Social reformers—Chicago—Illinois—History. 2. Social ethics—Chicago— Illinois—History. 3. Chicago (Ill.)—Social conditions. 4. United States—Social conditions—1865–1918. I. Title. HN80.C5W47 2007 303.48'40977311—dc22 2006100374 Cover design by Laurence J. Nozik Type set in Minion Printed by Thomson-Shore The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48-1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Westhoff 3.indb 4 5/14/2007 12:39:33 PM To Darel, Henry, and Jacob Westhoff 3.indb 5 5/14/2007 12:39:33 PM Westhoff 3.indb 6 5/14/2007 12:39:33 PM Contents Preface ix Acknowledgments xiii Introduction 1 Chapter 1. -

Секция1. Английский Язык Chemical Weapons

Секция1. Английский язык CHEMICAL WEAPONS (Химическое оружие) Д. Артемьева (студентка) D. Artemyeva (student) Научный руководитель: Г. А. Суромкина Scientific adviser: G.A. Suromkina (lecturer) Юридический Институт, ТМДк-210 The Institute of Law, group C-210 Ключевые слова ( key words): Weapons, toxic properties, chemical substances, chlo- rine, phosgene gas, poisoning agents, mustard gas bomb, global thermonuclear annihilation Аннотация: Статья рассматривает проблемы использования химического оружия в ретроспективе, а также последствия от его использования. В заключении статьи говорится о том, что синтез химического оружия доступен каждому высококвалифицированному специалисту. Chemical warfare is a military operation using lear annihilation was foremost in the minds of most the toxic properties of chemical substances to kill, during the Cold War, both the Soviet and Western injure or incapacitate the enemy. Chemical warfare is governments put enormous resources into developing different from the use of conventional weapons or chemical and biological weapons. Such weapons nuclear weapons because the destructive effects of were used in Vietnam War by U.S army. It was also chemical weapons are not primarily due to any explo- used during the Iran-Iraq War begun in 1980. Early sive force. Although rude chemical warfare has been in the conflict, Iraq began to employ mustard gas and employed in many parts of the world for thousands of tabun delivered by bombs dropped from airplanes; years, «modern» chemical warfare began during approximately 5 % of all Iranian casualties are direct- World War I. Initially, only well-known commercial- ly attributable to the use of these agents. Iraq and the ly available chemicals and their variants were used. -

Rezervirano Mjesto Za Tekst

The Story of Woman Anna Eleanor Roosevelt (born October 11, 1884, New York, New York, U.S. — died November 7, 1962, New York City, New York)) She was a leader in her own right and in volved in numerous humanitarian causes throughout her life. By the 1920s she was involved in Democratic Party politics and numerous social reform organizations. In the White House, she was one of the most active first ladies in history and worked for political, racial and social justice. After President Roosevelt’s death, Eleanor was a delegate to the United Nations and continued to serve as an advocate for a wide range of human rights issues. Find more on: https://www.history.com/topics/first-ladies/eleanor-roosevelt https://www.britannica.com/biography/Eleanor-Roosevelt Billie Jean King née Billie Jean Moffitt (born November 22, 1943, Long Beach, California, U.S.) American tennis player whose influence and playing style elevated the status of women’s professional tennis beginning in the late 1960s. In her career she won 39 major titles, competing in both singles and doubles. Find more on: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Billie-Jean-King https://www.billiejeanking.com/ Jerrie Mock Geraldine Lois Fredritz (born November 22, 1925, Newark, Ohio — died September 30, 2014, Quincy, Fla.) "Jerrie," was the first woman to fly around the world. On March 19, 1964, Mock took off from Columbus in her plane, the "Spirit of Columbus", a Cessna 180. Mock's trip around the world took twenty-nine days, eleven hours, and fifty-nine minutes, with the pilot returning to Columbus on April 17, 1964. -

CELEBRATING SIGNIFICANT CHICAGO WOMEN Park &Gardens

Chicago Women’s Chicago Women’s CELEBRATING SIGNIFICANT CHICAGO WOMEN CHICAGO SIGNIFICANT CELEBRATING Park &Gardens Park Margaret T. Burroughs Lorraine Hansberry Bertha Honoré Palmer Pearl M. Hart Frances Glessner Lee Margaret Hie Ding Lin Viola Spolin Etta Moten Barnett Maria Mangual introduction Chicago Women’s Park & Gardens honors the many local women throughout history who have made important contributions to the city, nation, and the world. This booklet contains brief introductions to 65 great Chicago women—only a fraction of the many female Chicagoans who could be added to this list. In our selection, we strived for diversity in geography, chronology, accomplishments, and ethnicity. Only women with substantial ties to the City of Chicago were considered. Many other remarkable women who are still living or who lived just outside the City are not included here but are still equally noteworthy. We encourage you to visit Chicago Women’s Park FEATURED ABOVE and Gardens, where field house exhibitry and the Maria Goeppert Mayer Helping Hands Memorial to Jane Addams honor Katherine Dunham the important legacy of Chicago women. Frances Glessner Lee Gwendolyn Brooks Maria Tallchief Paschen The Chicago star signifies women who have been honored Addie Wyatt through the naming of a public space or building. contents LEADERS & ACTIVISTS 9 Dawn Clark Netsch 20 Viola Spolin 2 Grace Abbott 10 Bertha Honoré Palmer 21 Koko Taylor 2 Jane Addams 10 Lucy Ella Gonzales Parsons 21 Lois Weisberg 2 Helen Alvarado 11 Tobey Prinz TRAILBLAZERS 3 Joan Fujisawa Arai 11 Guadalupe Reyes & INNOVATORS 3 Ida B. Wells-Barnett 12 Maria del Jesus Saucedo 3 Willie T. -

A Journey with Miss Ida B. Wells

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2018 Self-executed dramaturgy : a journey with Miss Ida B. Wells. Sidney Michelle Edwards University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, African History Commons, American Studies Commons, Fine Arts Commons, United States History Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Edwards, Sidney Michelle, "Self-executed dramaturgy : a journey with Miss Ida B. Wells." (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2956. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2956 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SELF-EXECUTED DRAMATURGY: A JOURNEY WITH MISS IDA B. WELLS By Sidney Michelle Edwards B.F.A., William Peace University, 2013 A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Louisville in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Theatre Arts Department of Theatre Arts University of Louisville Louisville, KY May 2018 Copyright, 2018 by Sidney Michelle Edwards ALL RIGHTS RESERVED SELF-EXECUTED DRAMATURGY: A JOURNEY WITH MISS IDA B. WELLS By Sidney Michelle Edwards B.F.A., William Peace University, 2013 Certification Approval on April 12, 2018 By the following Thesis Committee: __________________________________ Thesis Director, Johnny Jones ___________________________________ Dr. -

PROCLAMATION 6537—MAR. 19, 1993 107 STAT. 2629 Women's History Month, 1993

PROCLAMATION 6537—MAR. 19, 1993 107 STAT. 2629 Proclamation 6537 of March 19,1993 Women's History Month, 1993 By the President of the United States of America A Proclamation As we celebrate Women's History Month, we reflect on the American women who throughout history have proudly served in shaping the spirit of our Nation. Women like Harriet Tubman, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and Sojourner Truth embraced the struggle for human freedom, dignity, and justice. They opposed slavery and inequality at critical moments in history. Their courageous leadership helped pave the way for futiure genera tions who would strive to secure equal rights for women. We are inspired by women like Jane Addams, the flrst female Nobel prize winner, who at the tarn of the century founded Chicago's Hull House to help newly arrived immigrants adapt to a foreign culture. We admire women such as Belva Lockwood, who became the first woman admitted to practice before the United States Supreme Coiul in 1879. And we cannot forget the long struggle of women like Frances Perkins, whose work to protect the health and safety of America's workers cul minated in her service as Secretary of Labor, the Nation's first woman Cabinet officer. These courageous and pioneering women worked tirelessly to achieve new opportunities for all. Today, empowered by this great legacy, American women serve in every aspect of American life, from social services to space exploration. The opportunities for American women are growing, and their efforts as mothers and volunteers, corporate ex ecutives and senators, police officers and administrators, construction workers and cab drivers, and teachers and scientists enrich all of us and make our country great. -

Pebblego Biographies Article List

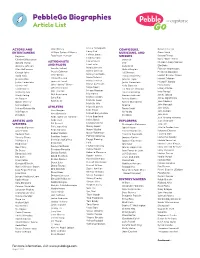

PebbleGo Biographies Article List Kristie Yamaguchi ACTORS AND Walt Disney COMPOSERS, Delores Huerta Larry Bird ENTERTAINERS William Carlos Williams MUSICIANS, AND Diane Nash LeBron James Beyoncé Zora Neale Hurston SINGERS Donald Trump Lindsey Vonn Chadwick Boseman Beyoncé Doris “Dorie” Miller Lionel Messi Donald Trump ASTRONAUTS BTS Elizabeth Cady Stanton Lisa Leslie Dwayne Johnson AND PILOTS Celia Cruz Ella Baker Magic Johnson Ellen DeGeneres Amelia Earhart Duke Ellington Florence Nightingale Mamie Johnson George Takei Bessie Coleman Ed Sheeran Frederick Douglass Manny Machado Hoda Kotb Ellen Ochoa Francis Scott Key Harriet Beecher Stowe Maria Tallchief Jessica Alba Ellison Onizuka Jennifer Lopez Harriet Tubman Mario Lemieux Justin Timberlake James A. Lovell Justin Timberlake Hector P. Garcia Mary Lou Retton Kristen Bell John “Danny” Olivas Kelly Clarkson Helen Keller Maya Moore Lynda Carter John Herrington Lin-Manuel Miranda Hillary Clinton Megan Rapinoe Michael J. Fox Mae Jemison Louis Armstrong Irma Rangel Mia Hamm Mindy Kaling Neil Armstrong Marian Anderson James Jabara Michael Jordan Mr. Rogers Sally Ride Selena Gomez James Oglethorpe Michelle Kwan Oprah Winfrey Scott Kelly Selena Quintanilla Jane Addams Michelle Wie Selena Gomez Shakira John Hancock Miguel Cabrera Selena Quintanilla ATHLETES Taylor Swift John Lewis Alex Morgan Mike Trout Will Rogers Yo-Yo Ma John McCain Alex Ovechkin Mikhail Baryshnikov Zendaya Zendaya John Muir Babe Didrikson Zaharias Misty Copeland Jose Antonio Navarro ARTISTS AND Babe Ruth Mo’ne Davis EXPLORERS Juan de Onate Muhammad Ali WRITERS Bill Russell Christopher Columbus Julia Hill Nancy Lopez Amanda Gorman Billie Jean King Daniel Boone Juliette Gordon Low Naomi Osaka Anne Frank Brian Boitano Ernest Shackleton Kalpana Chawla Oscar Robertson Barbara Park Bubba Wallace Franciso Coronado Lucretia Mott Patrick Mahomes Beverly Cleary Candace Parker Jacques Cartier Mahatma Gandhi Peggy Fleming Bill Martin Jr. -

AVAILABLE Fromnational Women's History Week Project, Women's Support Network, Inc., P.O

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 233 918 SO 014 593 TITLE Women's History Lesson Plan Sets. INSTITUTION Women's Support Network, Inc., Santa Rosa, CA. SPONS AGENCY Women's Educational Equity Act Program (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 83 NOTE 52p.; Prepared by the National Women's History Week Project. Marginally legible becalr,:e of colored pages and small print type. AVAILABLE FROMNational Women's History Week Project, Women's Support Network, Inc., P.O. Box 3716, Santa Rosa, CA 95402 ($8.00). PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use - Guides (For Teachers) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; *Art Educatien; Audiovisual Aids; Books; Elementary Secondary Education; *English Instruction; *Females; *Interdisciplinary Approach; Learning Activities; Lesson Plans; Models; Resource Materials; Sex Role; *United States History; *Womens Studies IDENTIFIERS Chronology; National Womens History Week Project ABSTRACT The materials offer concrete examples of how women contributed to U.S. history during three time periods: 1763-1786; 1835-1860; and 1907-1930. They can be used as the basis for an interdisciplinary K-12 program in social studies, English, and art. There are three major sections to the guide. The first section suggests lesson plans for each of the time periods under study. Lesson plans contain many varied learning activities. For example, students read and discuss books, view films, do library research, sing songs, study the art of quilt making, write journal entries of an imaginary trip west as young women, write speeches, and research the art of North American women. The second section contains a chronology outlining women's contributions to various events.