Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ICD10 Diagnoses FY2018 AHD.Com

ICD10 Diagnoses FY2018 AHD.com A020 Salmonella enteritis A5217 General paresis B372 Candidiasis of skin and nail A040 Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli A523 Neurosyphilis, unspecified B373 Candidiasis of vulva and vagina infection A528 Late syphilis, latent B3741 Candidal cystitis and urethritis A044 Other intestinal Escherichia coli A530 Latent syphilis, unspecified as early or B3749 Other urogenital candidiasis infections late B376 Candidal endocarditis A045 Campylobacter enteritis A539 Syphilis, unspecified B377 Candidal sepsis A046 Enteritis due to Yersinia enterocolitica A599 Trichomoniasis, unspecified B3781 Candidal esophagitis A047 Enterocolitis due to Clostridium difficile A6000 Herpesviral infection of urogenital B3789 Other sites of candidiasis A048 Other specified bacterial intestinal system, unspecified B379 Candidiasis, unspecified infections A6002 Herpesviral infection of other male B380 Acute pulmonary coccidioidomycosis A049 Bacterial intestinal infection, genital organs B381 Chronic pulmonary coccidioidomycosis unspecified A630 Anogenital (venereal) warts B382 Pulmonary coccidioidomycosis, A059 Bacterial foodborne intoxication, A6920 Lyme disease, unspecified unspecified unspecified A7740 Ehrlichiosis, unspecified B387 Disseminated coccidioidomycosis A080 Rotaviral enteritis A7749 Other ehrlichiosis B389 Coccidioidomycosis, unspecified A0811 Acute gastroenteropathy due to A879 Viral meningitis, unspecified B399 Histoplasmosis, unspecified Norwalk agent A938 Other specified arthropod-borne viral B440 Invasive pulmonary -

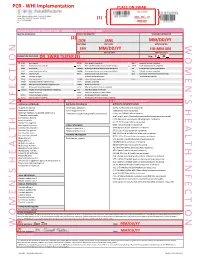

Womens Health Requisition Forms

PCR - WHI Implementation PLACE ON SWAB 10854 Midwest Industrial Blvd. St. Louis, MO 63132 MM DD YY Phone: (314) 200-3040 | Fax (314) 200-3042 (1) CLIA ID #26D0953866 JANE DOE v3 PCR MOLECULAR REQUISITION - WOMEN'S HEALTH INFECTION PRACTICE INFORMATION PATIENT INFORMATION *SPECIMEN INFORMATION (2) DOE JANE MM/DD/YY LAST NAME FIRST NAME DATE COLLECTED W O M E ' N S H E A L T H I F N E C T I O N SSN MM/DD/YY HH:MM AM SSN DATE OF BIRTH TIME COLLECTED REQUESTING PHYSICIAN: DR. SWAB TESTER (3) Sex: F X M (4) Diagnosis Codes X N76.0 Acute vaginitis B37.49 Other urogenital candidiasis A54.9 Gonococcal infection, unspecified N76.1 Subacute and chronic vaginitis N89.8 Other specified noninflammatory disorders of vagina A59.00 Urogenital trichomoniasis, unspecified N76.2 Acute vulvitis O99.820 Streptococcus B carrier state complicating pregnancy A64 Unspecified sexually transmitted disease N76.3 Subacute and chronic vulvitis O99.824 Streptococcus B carrier state complicating childbirth A74.9 Chlamydial infection, unspecified N76.4 Abscess of vulva B95.1 Streptococcus, group B, as the cause Z11.3 Screening for infections with a predmoninantly N76.5 Ulceration of vagina of diseases classified elsewhere sexual mode of trasmission N76.6 Ulceration of vulva Z22.330 Carrier of group B streptococcus Other: N76.81 Mucositis(ulcerative) of vagina and vulva N70.91 Salpingitis, unspecified N76.89 Other specified inflammation of vagina and vulva N70.92 Oophoritis, unspecified N95.2 Post menopausal atrophic vaginitis N71.9 Inflammatory disease of uterus, unspecified -

N35.12 Postinfective Urethral Stricture, NEC, Female N35.811 Other

N35.12 Postinfective urethral stricture, NEC, female N35.811 Other urethral stricture, male, meatal N35.812 Other urethral bulbous stricture, male N35.813 Other membranous urethral stricture, male N35.814 Other anterior urethral stricture, male, anterior N35.816 Other urethral stricture, male, overlapping sites N35.819 Other urethral stricture, male, unspecified site N35.82 Other urethral stricture, female N35.911 Unspecified urethral stricture, male, meatal N35.912 Unspecified bulbous urethral stricture, male N35.913 Unspecified membranous urethral stricture, male N35.914 Unspecified anterior urethral stricture, male N35.916 Unspecified urethral stricture, male, overlapping sites N35.919 Unspecified urethral stricture, male, unspecified site N35.92 Unspecified urethral stricture, female N36.0 Urethral fistula N36.1 Urethral diverticulum N36.2 Urethral caruncle N36.41 Hypermobility of urethra N36.42 Intrinsic sphincter deficiency (ISD) N36.43 Combined hypermobility of urethra and intrns sphincter defic N36.44 Muscular disorders of urethra N36.5 Urethral false passage N36.8 Other specified disorders of urethra N36.9 Urethral disorder, unspecified N37 Urethral disorders in diseases classified elsewhere N39.0 Urinary tract infection, site not specified N39.3 Stress incontinence (female) (male) N39.41 Urge incontinence N39.42 Incontinence without sensory awareness N39.43 Post-void dribbling N39.44 Nocturnal enuresis N39.45 Continuous leakage N39.46 Mixed incontinence N39.490 Overflow incontinence N39.491 Coital incontinence N39.492 Postural -

Diagnostic Tests for Vaginosis/Vaginitis

Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research Diagnostic tests for vaginosis/vaginitis Christa Harstall and Paula Corabian October 1998 HTA12 Diagnostic tests for vaginosis/vaginitis Christa Harstall and Paula Corabian October 1998 © Copyight Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research, 1998 This Health Technology Assessment Report has been prepared on the basis of available information of which the Foundation is aware from public literature and expert opinion, and attempts to be current to the date of publication. The report has been externally reviewed. Additional information and comments relative to the Report are welcome, and should be sent to: Director, Health Technology Assessment Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research 3125 Manulife Place, 10180 - 101 Street Edmonton Alberta T5J 3S4 CANADA Tel: 403-423-5727, Fax: 403-429-3509 This study is based, in part, on data provided by Alberta Health. The interpretation of the data in the report is that of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the Government of Alberta. ISBN 1-896956-15-7 Alberta's health technology assessment program has been established under the Health Research Collaboration Agreement between the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research and the Alberta Health Ministry. Acknowledgements The Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research is most grateful to the following persons for their comments on the draft report and for provision of information. The views expressed in the final report are those of the Foundation. Dr. Jane Ballantine, Section of General Practice, Calgary Dr. Deirdre L. Church, Microbiology, Calgary Laboratory Services, Calgary Dr. Nestor N. Demianczuk, Royal Alexandra Hospital, Edmonton Dr. -

Symptomatology of Endometriosis : with a Survey of 788 Cases Compiled from the Literature

University of Nebraska Medical Center DigitalCommons@UNMC MD Theses Special Collections 5-1-1938 Symptomatology of endometriosis : with a survey of 788 cases compiled from the literature Paul Milton Pedersen University of Nebraska Medical Center This manuscript is historical in nature and may not reflect current medical research and practice. Search PubMed for current research. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unmc.edu/mdtheses Part of the Medical Education Commons Recommended Citation Pedersen, Paul Milton, "Symptomatology of endometriosis : with a survey of 788 cases compiled from the literature" (1938). MD Theses. 688. https://digitalcommons.unmc.edu/mdtheses/688 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections at DigitalCommons@UNMC. It has been accepted for inclusion in MD Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNMC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SYMPTOMATOLOGY OF ENDOMETRIOSIS WITH A SURVEY OF 788 CASES COMPILED FROM LITERATURE SENIOR THESIS PAUL MILTON PEDERSEN *** j I !,' i PRESENTED TO THE THE UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA OJIAHA., 1938 .. 480965 THE SYMPTOMATOLOGY OF ENDOMETRIOSIS WITH A SURVEY OF 788 CASES COMPILED FROM LITERATURE Introduction. The history of this disease is very similar to that of many others in that it has been developed as a clinical entity within the past twenty years. The present day knowledge of the subject is not as general as it might· be considering the relatively numerous articles which have appeared upon this subject within the past five years. Endometriosis is a very intriguing subject; the unique features in the symptoms that it provokes are indeed class ical, and the interest with which this is regarded has caused us to consider that phase in detail. -

Amenorrhea in Teenagers in Concepts of Homoeopathy

Amenorrhea in Teenagers in concepts of Homoeopathy © Dr. Rajneesh Kumar Sharma MD (Homoeopathy) Homoeo Cure Research Institute NH 74- Moradabad Road Kashipur (UTTARANCHAL) - INDIA Ph- 09897618594 E. mail- [email protected] www.homeopathictreatment.org.in www.treatmenthomeopathy.com www.homeopathyworldcommunity.com Introduction Menstrual irregularities are common within first 2–3 years after menarche. If amenorrhea is prolonged, it is abnormal and can be associated with some major disease, depending on the adolescent whether she is oestrogen-deficient or oestrogen-replete. Oestrogen-deficient amenorrhea (Psora) is concomitant with reduced bone mineral density (Syphilis) and increased fracture risk, while oestrogen-replete amenorrhea (Syphilis) can lead to dysfunctional uterine bleeding in the short term (Pseudopsora/ Sycosis) and predispose to endometrial carcinoma (Cancerous) in the long term. Hypothalamic amenorrhea (Psora) is predominant cause of amenorrhea in the adolescents and often leads to polycystic ovary syndrome (Pseudopsora/ Sycosis). In anorexia nervosa (Psora), exercise- induced amenorrhea (Causa occasionalis) and chronic illness amenorrhea, energy shortage results in suppression of GnRH secretion (Psora) by hypothalamus. Normal Menstrual Cycle Menarche Menarche is the time when a girl has her first menstrual period. It usually occurs between the ages of 10 and 14 years. Physiology Stimulation of Pituitary Neurosecretory neurons of the preoptic area of the hypothalamus secrete a decapeptide, called Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH). This hormone is poured into the capillaries of the hypophysial portal system which transport it to the anterior pituitary, where it stimulates (Psora) the synthesis and secretion of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). Control of GnRH The GnRH is released in rhythms in response to serum levels of gonadal steroids. -

The Differential Diagnosis of Acute Pelvic Pain in Various Stages of The

Osteopathic Family Physician (2011) 3, 112-119 The differential diagnosis of acute pelvic pain in various stages of the life cycle of women and adolescents: gynecological challenges for the family physician in an outpatient setting Maria F. Daly, DO, FACOFP From Jackson Memorial Hospital, Miami, FL. KEYWORDS: Acute pain is of sudden onset, intense, sharp or severe cramping. It may be described as local or diffuse, Acute pain; and if corrected takes a short course. It is often associated with nausea, emesis, diaphoresis, and anxiety. Acute pelvic pain; It may vary in intensity of expression by a woman’s cultural worldview of communicating as well as Nonpelvic pain; her history of physical, mental, and psychosocial painful experiences. The primary care physician must Differential diagnosis dissect in an orderly, precise, and rapid manner the true history from the patient experiencing pain, and proceed to diagnose and treat the acute symptoms of a possible life-threatening problem. © 2011 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Introduction female’s presentation of acute pelvic pain with an enlarged bulky uterus may often be diagnosed as a leiomyoma in- Women at various ages and stages of their life cycle may stead of a neoplastic mass. A pregnant female, whose preg- present with different causes of acute pelvic pain. Estab- nancy is either known to her or unknown, presenting with lishing an accurate diagnosis from the multiple pathologies acute pelvic pain must be rapidly evaluated and treated to in the differential diagnosis of their specific pelvic pain may prevent a rapid downward cascading progression to mater- well be a challenge for the primary care physician. -

Remarks on Pelvic Peritonitis and Pelvic Cellulitis, with Illustrative Cases

Article IV.- Remarks on Pelvic Peritonitis and Pelvic Cellulitis, with Illustrative Cases. By Lauchlan Aitken, M.D. Rather moie than a year ago there appeared from the pen of a well- known of this a gynecologist city very able monograph on the two forms of pelvic inflammation whose names head this article; and it cannot have escaped the recollection of the reader that Dr M. Dun- can, adopting the nomenclature first proposed by Yirchow, has used on his different terms title-page1 than those older appellations I still to retain. Under these propose ^ circumstances I feel at to compelled least to attempt justify my preference for the original names: and I trust to be able to show that are they preferable to, and less con- others that fusing than, any have as yet been proposed, even though we cannot consider them absolutely perfect. 1 Treatise on A Practical Perimetritis and Parametritis (Edin. 1869). 1870.] DR LAUCI1LAN AITKEN ON PELVIC FERITONITIS, ETC. 889 Passing over, then, such terms as 'periuterine cellulitis or phleg- mons periuterins as bad compounds ; others, as inflammation of the broad ligaments, as too limited in meaning ; and others, again, as engorgement periutdrin, as only indicating one of the stages of the affection,?I shall endeavour as succinctly as possible to state my reasons for preferring the older names to those proposed by Virchow. ls?. The two Greek prepositions, peri and para, are employed somewhat arbitrarily to indicate inflammatory processes which are essentially distinct. I say arbitrarily, because I am not aware that para has been generally employed in the form of a compound to ex- press inflammation of the cellular tissue elsewhere.1 By those who remember that the cellular tissue not only separates the serous membrane from the uterus at that part where the cervix and body of the organ meet, but is even abundant there,2 perimetritis might readily be taken to indicate one of the varieties, though indeed not a in for which very common one, of pelvic cellulitis?a variety, fact, the term perimetric cellulitis has been proposed. -

The Characteristics and Risk Factors of Human Papillomavirus

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN The characteristics and risk factors of human papillomavirus infection: an outpatient population‑based study in Changsha, Hunan Bingsi Gao 1, Yu‑Ligh Liou2, Yang Yu1, Lingxiao Zou1, Waixing Li1, Huan Huang1, Aiqian Zhang1, Dabao Xu 1,3* & Xingping Zhao 1,3* This cross‑sectional study investigated the characteristics of cervical HPV infection in Changsha area and explored the infuence of Candida vaginitis on this infection. From 11 August 2017 to 11 September 2018, 12,628 outpatient participants ranged from 19 to 84 years old were enrolled and analyzed. HPV DNA was amplifed and tested by HPV GenoArray Test Kit. The vaginal ecology was detected by microscopic and biochemistry examinations. The diagnosis of Candida vaginitis was based on microscopic examination (spores, and/or hypha) and biochemical testing (galactosidase) for vaginal discharge by experts. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4. Continuous and categorical variables were analyzed by t‑tests and by Chi‑square tests, respectively. HPV infection risk factors were analyzed using multivariate logistic regression. Of the total number of participants, 1753 were infected with HPV (13.88%). Females aged ≥ 40 to < 50 years constituted the largest population of HPV‑infected females (31.26%). The top 5 HPV subtypes afecting this population of 1753 infected females were the following: HPV‑52 (28.01%), HPV‑58 (14.83%), CP8304 (11.47%), HPV‑53 (10.84%), and HPV‑39 (9.64%). Age (OR 1.01; 95% CI 1–1.01; P < 0.05) and alcohol consumption (OR 1.30; 95% CI 1.09–1.56; P < 0.01) were found to be risk factors for HPV infection. -

The Relative Risk

Clinical Expert Series Pelvic Inflammatory Disease David E. Soper, MD Obstet Gynecol 2010;116(2) ACCME Accreditation The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) to provide continuing medical education for physicians. (Continuing medical education credit for “Pelvic Inflammatory Disease” will be available through August 2013.) AMA PRA Category 1 CreditTM and ACOG Cognate Credit The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) designates this educational activity for a maximum of 2 AMA PRA Category 1 CreditsTM or up to a maximum of 2 Category 1 ACOG cognate credits. Physicians should only claim credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity. Disclosure Statement Current guidelines state that continuing medical education (CME) providers must ensure that CME activities are free from the control of any commercial interest. All authors, reviewers, and contributors have disclosed to the College all relevant financial relationships with any commercial interests. The authors, reviewers, and contributors declare that neither they nor any business associate nor any member of their immediate families has financial interest or other relationships with any manufacturer of products or any providers of services discussed in this program. Any conflicts have been resolved through group and outside review of all content. Before submitting this form, please print a completed copy as confirmation of your program participation. ACOG Fellows: To obtain credits, complete and return this form by clicking on “Submit” at the bottom of the page. Credit will be automatically recorded upon receipt and online transcripts will be updated twice monthly. -

Infektionen an Vulva, Vagina Und Zervix Literarische Übersichtsarbeit Und Internetkompendium

Aus der Klinik und Poliklinik für Frauenheilkunde und Geburtshilfe der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München Direktor: Prof. Dr. med. K. Friese Infektionen an Vulva, Vagina und Zervix Literarische Übersichtsarbeit und Internetkompendium Dissertation zum Erwerb des Doktorgrades der Medizin an der Medizinischen Fakultät der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München vorgelegt von Andrea Buchberger aus Dachau 2009 Abstract Die literarische Übersichtsarbeit und das Internetkompendium zur Thematik Infektionen an Vulva, Vagina und Zervix zeichnen sich durch große epidemiologische Bedeutung und fachliche Brisanz aus. Auf 265 Seiten werden 654 Fachartikel der vergangenen Dekade zitiert, 90 Abbildungen und Tabellen strukturieren die Flut an Daten. Die originäre Leistung liegt im Internetkompendium, das eine gute Übersicht über genitale Infektionen verschafft. Die wissenschaftlich fundierten Aussagen aus dem Grundlagenteil werden hier komprimiert auf einer Startseite zusammengefügt, in den tieferen Ebenen sind weiterführende Kommentare verlinkt. In einem diagnosebezogenen und in einem symptomorientierten Bereich sowie einen Abschnitt zur Prävention hat der Laie raschen Zugriff auf die für ihn relevanten Informationen. Genitalinfektionen sind häufig: Fast alle Frauen sind im Laufe ihres Lebens wenigstens einmal davon betroffen, viele leiden an rezidivierenden Verläufen. Auch die Inzidenz sexuell übertragbarer Krankheiten ist weltweit, in Europa und auch in Deutschland zunehmend. Doch die geschichtlichen Wurzeln reichen weit zurück: Seit alters her wurden zahlreiche Therapieoptionen ersonnen, in der Einleitung wird ein kurzer geschichtlicher Abriss gegeben. Im Anschluss daran folgt die Aufgabenstellung in der die Teile der Arbeit erläutert werden. Auch das System der Literaturrecherche wird beschrieben: Im Wesentlichen fand sie über das Internet statt, doch auch die Universitätsbibliothek in Großhadern, die medizinische Lesehalle und über Fernleihe die Bayerische Staatsbibliothek waren wichtige Literaturquellen. -

Prevotella Biva Poster.Pptx

Novel Infection Status Post Electrocution Requiring a 4th Ray Amputation WilliamJudson IV, D.O.1, John Murphy, D.O.1, Phillip Sussman, D.O.1, John Harker D.O.1 HCA Healthcare/USF Morsani College of Medicine GME Programs/Largo Medical Center Background Treatment • Prevotella bivia is an anaerobic, non-pigmented, Gram-negative bacillus species that is known to inhabit the human female vaginal tract and oral flora. It is most commonly associated with endometritis and pelvic inflammatory disease.1, 2 • Rarely, P. bivia has been found in the nail bed, chest wall, intervertebral discs, and hip and knee joints.1 The bacteria has been linked to necrotizing fasciitis, osteomyelitis, or septic arthritis.3, 4 • Only 3 other reports have described P. bivia infections in the upper Figure 1: Dorsum of the right hand on Figure 2: Ulnar aspect of right 4th and 5th Figures 13 and 14: Most recent images of patients hand in March, 2020. 2 presentation fingers Wound over the dorsum of the hand completely healed. Patient with flexion extremity with one patient requiring amputation , and one with deep soft contractures of remaining digits. tissue infection requiring multiple debridements and extensive tenosynovectomy.5 Discussion • Delays in diagnosis are common due to P. bivia’s long incubation period • P. bivia infections, although rare in orthopedic practice, can lead to and association with aerobic organisms that more commonly cause soft extensive debridements and possible amputation leading to great tissue infections leading to inappropriate antibiotic coverage. morbidity when affecting the upper extremities.1, 2, 5 • Here we present a case on P.