Marker of Death a Note on the Swastika in Attic Geometric Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Instruction Manual

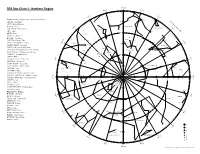

1 Contents 1. Constellation Watch Cosmo Sign.................................................. 4 2. Constellation Display of Entire Sky at 35° North Latitude ........ 5 3. Features ........................................................................................... 6 4. Setting the Time and Constellation Dial....................................... 8 5. Concerning the Constellation Dial Display ................................ 11 6. Abbreviations of Constellations and their Full Spellings.......... 12 7. Nebulae and Star Clusters on the Constellation Dial in Light Green.... 15 8. Diagram of the Constellation Dial............................................... 16 9. Precautions .................................................................................... 18 10. Specifications................................................................................. 24 3 1. Constellation Watch Cosmo Sign 2. Constellation Display of Entire Sky at 35° The Constellation Watch Cosmo Sign is a precisely designed analog quartz watch that North Latitude displays not only the current time but also the correct positions of the constellations as Right ascension scale Ecliptic Celestial equator they move across the celestial sphere. The Cosmo Sign Constellation Watch gives the Date scale -18° horizontal D azimuth and altitude of the major fixed stars, nebulae and star clusters, displays local i c r e o Constellation dial setting c n t s ( sidereal time, stellar spectral type, pole star hour angle, the hours for astronomical i o N t e n o l l r f -

Naming the Extrasolar Planets

Naming the extrasolar planets W. Lyra Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, K¨onigstuhl 17, 69177, Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Abstract and OGLE-TR-182 b, which does not help educators convey the message that these planets are quite similar to Jupiter. Extrasolar planets are not named and are referred to only In stark contrast, the sentence“planet Apollo is a gas giant by their assigned scientific designation. The reason given like Jupiter” is heavily - yet invisibly - coated with Coper- by the IAU to not name the planets is that it is consid- nicanism. ered impractical as planets are expected to be common. I One reason given by the IAU for not considering naming advance some reasons as to why this logic is flawed, and sug- the extrasolar planets is that it is a task deemed impractical. gest names for the 403 extrasolar planet candidates known One source is quoted as having said “if planets are found to as of Oct 2009. The names follow a scheme of association occur very frequently in the Universe, a system of individual with the constellation that the host star pertains to, and names for planets might well rapidly be found equally im- therefore are mostly drawn from Roman-Greek mythology. practicable as it is for stars, as planet discoveries progress.” Other mythologies may also be used given that a suitable 1. This leads to a second argument. It is indeed impractical association is established. to name all stars. But some stars are named nonetheless. In fact, all other classes of astronomical bodies are named. -

Educator's Guide: Orion

Legends of the Night Sky Orion Educator’s Guide Grades K - 8 Written By: Dr. Phil Wymer, Ph.D. & Art Klinger Legends of the Night Sky: Orion Educator’s Guide Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………....3 Constellations; General Overview……………………………………..4 Orion…………………………………………………………………………..22 Scorpius……………………………………………………………………….36 Canis Major…………………………………………………………………..45 Canis Minor…………………………………………………………………..52 Lesson Plans………………………………………………………………….56 Coloring Book…………………………………………………………………….….57 Hand Angles……………………………………………………………………….…64 Constellation Research..…………………………………………………….……71 When and Where to View Orion…………………………………….……..…77 Angles For Locating Orion..…………………………………………...……….78 Overhead Projector Punch Out of Orion……………………………………82 Where on Earth is: Thrace, Lemnos, and Crete?.............................83 Appendix………………………………………………………………………86 Copyright©2003, Audio Visual Imagineering, Inc. 2 Legends of the Night Sky: Orion Educator’s Guide Introduction It is our belief that “Legends of the Night sky: Orion” is the best multi-grade (K – 8), multi-disciplinary education package on the market today. It consists of a humorous 24-minute show and educator’s package. The Orion Educator’s Guide is designed for Planetarians, Teachers, and parents. The information is researched, organized, and laid out so that the educator need not spend hours coming up with lesson plans or labs. This has already been accomplished by certified educators. The guide is written to alleviate the fear of space and the night sky (that many elementary and middle school teachers have) when it comes to that section of the science lesson plan. It is an excellent tool that allows the parents to be a part of the learning experience. The guide is devised in such a way that there are plenty of visuals to assist the educator and student in finding the Winter constellations. -

Greece: Interactive Exploration

Greece: Interactive Exploration Who were the Ancient Greeks? Explore more about the Ancient Greeks and what they valued as a society. Grade Level: Grades 3-5, Grades 6-8, Grades 9-12 Collection: Ancient Art Culture/Region: Greece Subject Area: Creative Thinking, Critical Thinking, Fine Arts, History and Social Science, Visual Arts Activity Type: Art in Depth LOOKING, THINKING, AND LEARNING This resource will consist of two different types of looking, thinking and learning activities. These activities call on your observation and thinking skills as you closely examine selected objects from Ancient Greece. The activities will explore the themes of mythology, religion, sport and trade. LOOK AT THIS! Look at This activities provide close-up views with guiding questions and background information. What will you learn about what the ancient Greeks valued? SURPRISE ME! Surprise Me investigations offer pop-up hot spots on selected objects to reveal intriguing information about Greek religion, gods, goddesses, trade, sport and mythology. How do these objects relate to the Greek religion and human need for protection from harm and healing from disease and injury? WHO WERE THE GREEKS? Ancient Greece was not a unified country, but a collection of city-states. A city-state was a city and the surrounding towns that all followed the same law. The most famous city-state from Ancient Greece was Athens. Although there were many city-states with different laws, they shared certain cultural aspects that allow us to speak of a Greek Civilization. They had a common language and in general worshipped the same gods and goddesses. -

The Argo Navis Constellation

THE ARGO NAVIS CONSTELLATION At the last meeting we talked about the constellation around the South Pole, and how in the olden days there used to be a large ship there that has since been subdivided into the current constellations. I could not then recall the names of the constellations, but remembered that we talked about this subject at one of the early meetings, and now found it in September 2011. In line with my often stated definition of Astronomy, and how it seems to include virtually all the other Philosophy subjects: History, Science, Physics, Biology, Language, Cosmology and Mythology, lets go to mythology and re- tell the story behind the Argo Constellation. Argo Navis (or simply Argo) used to be a very large constellation in the southern sky. It represented the ship The Argo Navis ship with the Argonauts on board used by the Argonauts in Greek mythology who, in the years before the Trojan War, accompanied Jason to Colchis (modern day Georgia) in his quest to find the Golden Fleece. The ship was named after its builder, Argus. Argo is the only one of the 48 constellations listed by the 2nd century astronomer Ptolemy that is no longer officially recognised as a constellation. In 1752, the French astronomer Nicolas Louis de Lacaille subdivided it into Carina (the keel, or the hull, of the ship), Puppis (the poop deck), and Vela (the sails). The constellation Pyxis (the mariner's compass) occupies an area which in antiquity was considered part of Argo's mast (called Malus). The story goes that, when Jason was 20 years old, an oracle ordered him to head to the Iolcan court (modern city of Volos) where king Pelias was presiding over a sacrifice to Poseidon with several neighbouring kings in attendance. -

Presented by J.-Ph. Bernard (IRAP) Toulouse Planck Collaboration

Polarization results from Planck - Methods & data used - All sky polarization at 353 GHz - Highest dust polarization regions - Comparison to starlight polarization - Spectral variations of polarization fraction - Spatial variations of polarization fraction - Connections with large-scale MW B field, dust column density and small-scale B field structure Planck Collaboration. Presented by J.-Ph. Bernard (IRAP) Toulouse Bernard J.Ph., Ringberg Castle 2013 1 jeudi 27 juin 13 Dust Polarization BG: - Rotating, elongated and align partially on B - Produce polarized emission & extinction - Only large grains align Possible alignment mechanisms: - Paramagnetic relaxation alignment - Radiative Alignment Torques (RATs) Grain disalignment by: - Gas/grain collisions - Plasma drag extinction // to B Draine & Fraisse 2009 emission ⊥ to B Bernard J.Ph., Ringberg Castle 2013 2 jeudi 27 juin 13 Dust Polarization Compiegne et al., (2011) Draine & Fraisse 2009 polarization in PAH VSG emission is Spherical Graphite predicted ~10-15% BG Same b/a Compiegne et al., (2011) Various possible models lead to different predictions in polarization Variations of polarization fraction with frequency will help constrain dust models Bernard J.Ph., Ringberg Castle 2013 3 jeudi 27 juin 13 From data to Stokes parameters Planck scanning the sky Planck/HFI focal plane Derivation of Stokes parameters (I, Q and U) involves the combination of two pairs of PSB bolometers that observe the same sky positions within a few seconds. The polarizers of the second pair are rotated by 45° with respect to the first pair. Multiple scans and multiple surveys provide Q and U measurements with different orientation. Maps of Q and U and their standard deviations are inferred from the multiple measurements. -

Aegean Bronze Age Rhyta Type III S Conical, Boxer Rhyton (651)

Aegean Bronze Age Rhyta Type III S Conical, Boxer Rhyton (651). Reconstruction drawing by R. Porter (see also Fig. 29). PREHISTORY MONOGRAPHS 19 Aegean Bronze Age Rhyta by Robert B. Koehl Published by INSTAP Academic Press Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 2006 Design and Production INSTAP Academic Press Printing CRWGraphics, Pennsauken, New Jersey Binding Hoster Bindery, Inc., Ivyland, Pennsylvania Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Koehl, Robert B. Aegean Bronze Age rhyta / by Robert B. Koehl. p. cm. — (Prehistory monographs ; 19) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-931534-16-0 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Aegean Sea Region—Antiquities. 2. Rhyta—Aegean Sea Region. 3. Bronze age—Aegean Sea Region. I. Title. II. Series. DF220.K64 2006 938’.01—dc22 2006027437 Copyright © 2006 INSTAP Academic Press Philadelphia, Pennsylvania All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America In honor of my mother, Ruth and to the memory of my father, Seymour Table of Contents LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS IN THE TEXT . ix LIST OF TABLES . xi LIST OF FIGURES . xiii LIST OF PLATES . xv PREFACE . xix ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . xxiii LIST OF DRAWING CREDITS . xxvii LIST OF PHOTOGRAPHIC CREDITS . xxix ABBREVIATIONS AND CONVENTIONS . xxxi INTRODUCTION . 1 1. TYPOLOGY, HISTORY, AND DEVELOPMENT . 5 Principle of Typology and Definition of Types . 5 Definition of Classes and Their Nomenclature . 7 Rhyton Groups: Typology of Rims, Handles, and Bases . 7 Exclusions and Exceptions . 9 Organization and Presentation . 12 Aegean Rhyta . 13 Type I . 13 Type II . 21 Type III . 38 Type IV . 53 Type Indeterminate . 64 Foreign Imitations of Aegean Rhyta . 64 viii AEGEAN BRONZE AGE RHYTA 2. -

Perfume Vessels in South-East Italy

Perfume Vessels in South-East Italy A Comparative Analysis of Perfume Vessels in Greek and Indigenous Italian Burials from the 6th to 4th Centuries B.C. Amanda McManis Department of Archaeology Faculty of Arts University of Sydney October 2013 2 Abstract To date there has been a broad range of research investigating both perfume use in the Mediterranean and the cultural development of south-east Italy. The use of perfume was clearly an important practice in the broader Mediterranean, however very little is known about its introduction to the indigenous Italians and its subsequent use. There has also been considerable theorising about the nature of the cross-cultural relationship between the Greeks and the indigenous Italians, but there is a need for archaeological studies to substantiate or refute these theories. This thesis therefore aims to make a relevant contribution through a synthesis of these areas of study by producing a preliminary investigation of the use of perfume vessels in south-east Italy. The assimilation of perfume use into indigenous Italian culture was a result of their contact with the Greek settlers in south-east Italy, however the ways in which perfume vessels were incorporated into indigenous Italian use have not been systematically studied. This thesis will examine the use of perfume vessels in indigenous Italian burials in the regions of Peucetia and Messapia and compare this use with that of the burials at the nearby Greek settlement of Metaponto. The material studied will consist of burials from the sixth to fourth centuries B.C., to enable an analysis of perfume use and social change over time. -

SFA Star Chart 1

Nov 20 SFA Star Chart 1 - Northern Region 0h Dec 6 Nov 5 h 23 30º 1 h d Dec 21 h p Oct 21h s b 2 h 22 ANDROMEDA - Daughter of Cepheus and Cassiopeia Mirach Local Meridian for 8 PM q m ANTLIA - Air Pumpe p 40º APUS - Bird of Paradise n o i b g AQUILA - Eagle k ANDROMEDA Jan 5 u TRIANGULUM AQUARIUS - Water Carrier Oct 6 h z 3 21 LACERTA l h ARA - Altar j g ARIES - Ram 50º AURIGA - Charioteer e a BOOTES - Herdsman j r Schedar b CAELUM - Graving Tool x b a Algol Jan 20 b o CAMELOPARDALIS - Giraffe h Caph q 4 Sep 20 CYGNUS k h 20 g a 60º z CAPRICORNUS - Sea Goat Deneb z g PERSEUS d t x CARINA - Keel of the Ship Argo k i n h m a s CASSIOPEIA - Ethiopian Queen on a Throne c h CASSIOPEIA g Mirfak d e i CENTAURUS - Half horse and half man CEPHEUS e CEPHEUS - Ethiopian King Alderamin a d 70º CETUS - Whale h l m Feb 5 5 CHAMAELEON - Chameleon h i g h 19 Sep 5 i CIRCINUS - Compasses b g z d k e CANIS MAJOR - Larger Dog b r z CAMELOPARDALIS 7 h CANIS MINOR - Smaller Dog e 80º g a e a Capella CANCER - Crab LYRA Vega d a k AURIGA COLUMBA - Dove t b COMA BERENICES - Berenice's Hair Aug 21 j Feb 20 CORONA AUSTRALIS - Southern Crown Eltanin c Polaris 18 a d 6 d h CORONA BOREALIS - Northern Crown h q g x b q 30º 30º 80º 80º 40º 70º 50º 60º 60º 70º 50º CRATER - Cup 40º i e CRUX - Cross n z b Rastaban h URSA CORVUS - Crow z r MINOR CANES VENATICI - Hunting Dogs p 80º b CYGNUS - Swan h g q DELPHINUS - Dolphin Kocab Aug 6 e 17 DORADO - Goldfish q h h h DRACO o 7 DRACO - Dragon s GEMINI t t Mar 7 EQUULEUS - Little Horse HERCULES LYNX z i a ERIDANUS - River j -

81 Southern Objects for a 10” Telescope. 0-4Hr 4-8Hr 8-12Hr

81 southern objects for a 10” telescope. 0-4hr NGC55|00h 15m 22s|-39 11’ 35”|33’x 5.6’|Sculptor|Galaxy| NGC104|00h 24m 17s|-72 03’ 30”|31’|Tucana|Globular NGC134|00h 30m 35s|-33 13’ 00”|8.5’x2’|Sculptor|Galaxy| ESO350-40|00h 37m 55s|-33 41’ 20”|1.5’x1.2’|Sculptor|Galaxy|The Cartwheel NGC300|00h 55m 06s|-37 39’ 24”|22’x15.5’|Sculptor|Galaxy| NGC330|00h 56m 27s|-72 26’ 37”|Tucana|1.9’|SMC open cluster| NGC346|00h 59m 14s|-72 09’ 19”|Tucana|5.2’|SMC Neb| ESO351-30|01h 00m 22s|-33 40’ 50”|60’x56’|Sculptor|Galaxy|Sculptor Dwarf NGC362|01h 03m 23s|-70 49’ 42”|13’|Tucana|Globular| NGC2573| 01h 37m 21s|-89 25’ 49”|Octans| 2.0x 0.8|galaxy|polarissima australis| NGC1049|02h 39m 58s|-34 13’ 52”|24”|Fornax|Globular| ESO356-04|02h 40m 09s|-34 25’ 43”|60’x100’|Fornax|Galaxy|Fornax Dwarf NGC1313|03h 18m 18s|-66 29’ 02”|9.1’x6.3’|Reticulum|Galaxy| NGC1316|03h 22m 51s|-37 11’ 22”|12’x8.5’|Fornax|Galaxy| NGC1365|03h 33m 46s|-36 07’ 13”|11.2’x6.2’|Fornax|Galaxy NGC1433|03h 42m 08s|-47 12’ 18”|6.5’x5.9’|Horologium|Galaxy| 4-8hr NGC1566|04h 20m 05s|-54 55’ 42”|Dorado|Galaxy| Reticulum Dwarf|04h 31m 05s|-58 58’ 00”|Reticulum|LMC globular| NGC1808|05h 07m 52s|-37 30’ 20”|6.4’x3.9’|Columba|Galaxy| Kapteyns Star|05h 11m 35s|-45 00’ 16”|Stellar|Pictor|Nearby star| NGC1851|05h 14m 15s|-40 02’ 30”|11’|Columba|Globular| NGC1962group|05h 26m 17s|-68 50’ 28”|?| Dorado|LMC neb/cluster NGC1968group|05h 27m 22s|-67 27’ 36”|12’ for group|Dorado| LMC Neb/cluster| NGC2070|05h 38m 37s|-69 05’ 52”|11’|Dorado|LMC Neb|Tarantula| NGC2442|07h 36m 24s|-69 32’ 38”|5.5’x4.9’|Volans|Galaxy|The meat hook| NGC2439|07h 40m 59s|-31 38’36”|10’|Puppis|Open Cluster| NGC2451|07h 45m 35s|-37 57’ 27”|45’|Puppis|Open Cluster| IC2220|07h 56m 57s|-59 06’ 00”|6’x4’|Carina|Nebula|Toby Jug| NGC2516|07h 58m 29s|-60 51’ 46”|29’|Carina|Open Cluster 8-12hr NGC2547|08h 10m 50s|-49 15’ 39”|20’|Vela|Open Cluster| NGC2736|09h 00m 27s|-45 57’ 49”|30’x7’|Vela|SNR|The Pencil| NGC2808|09h 12m 08s|-64 52’ 48”|12’|Carina|Globular| NGC2818|09h 16m 11s|-36 35’ 59”|9’|Pyxis|Open Cluster with planetary. -

A Bucket, by Any Other Name, and an Athenian Stranger in Early Iron Age Crete (Plates15-16)

A BUCKET, BY ANY OTHER NAME, AND AN ATHENIAN STRANGER IN EARLY IRON AGE CRETE (PLATES15-16) O NE OF THE MORE INTERESTING, if not amusing, examples of the common accidentsthat can befalla potteris offeredby a vesselfound in the areaof the laterAthenian Agora.It was originallydesigned as a hydriabut was laterremodeled, prior to firing,into a krater. Publishedas a full-fledgedand "handsome"krater in an earlypreliminary report,1 soon afterits discovery,the vase, Agora P 6163 (Fig. 1; P1. 15:a),was to have receivedfuller treatment in the EarlyIron Age volumein the AthenianAgora series. Such a distinguishedvenue would normally havesufficed the publicationof the pot, but apartfrom its own intrinsicinterest, it contributesto a smallCretan problem that has neverbeen adequatelyaddressed. Moreover, the originaltype of vesselfrom which P 6163 is likelyto havebeen cut can be illustratedby a pot in the laterAthenian Kerameikos.2For these reasons,Agora P 6163 is publishedhere in the companyof its friend, Fortetsa454 (P1.16:d),3 and in closeproximity to its alterego, or id, Kerameikos783 (P1.15:b).4 Beforedescribing Agora P 6163, it wouldbe usefulto summarizeits contextand establishits date, especiallysince datinga vesselsuch as this one on the basis of style alone would, at best, representan arbitraryguess. Agora P 6163 was found in a well (depositL 6:2). Clearanceof late walls immediatelyto the south of the Athens-Piraeusrailway in 1935 led to the discovery of this well, which is locatedonly about 50 m south of the EridanosRiver and about 12 m east of the southeastcorner of the Peribolosof the TwelveGods. The mouth of the well, measuring 1.60 m east-westby 1.15 m north-south,was encounteredat a depth of 6 m below the modern groundlevel, and its shaftextended another 5.50 m in depth. -

VESSELS of the GODS Treasures of the Ancient Greeks

The International Museum Institute of New York presents VESSELS OF THE GODS Treasures of the Ancient Greeks 1650 – 410 B.C. Reflecting the brilliance of a millennium of ancient Aegean culture, four distinct periods produced the designs of these vases: Minoan, Mycenaean, Corinthian and Attic. Essentially consisting of silhouetted figures drawn against a background of red, black, or white, this art form gradually dies out after the Persian wars, c. 475-450 B.C. Shaped and painted by hand, these exquisite reproductions were created in Greece by master artists from the originals housed in The National Museum, Athens, The Heraklion Museum, The Thera Museum, The Corinth Museum, The Delphi Museum, The Louvre Museum, The Vatican Museum, and The Museo Civico, Brescia. MINOAN 1. Phaestos Disc c. 1650 B.C. The early writing of the tribal islanders of Crete and Santorini, the mysterious forerunners of the Greeks known as the Minoans, marks their emergence from the Stone Age at the beginning of the second millennium B.C. This enigmatic clay tablet, found in Crete and engraved in the elusive Linear A script, remains undeciphered. 2. Mistress of the Snakes c. 1600 B.C. Crowned with opium poppy pods surmounted by a crouching lion cub associating the figure with a royal house, this faience votive offering was found in a storage chamber of the Palace of Knossos on the island of Crete. The statuette either represents a deity or an agricultural fertility cult priestess, traditionally garbed as the Cretan Earth Mother goddess she served, carrying a pair of serpents as symbols of seasonal death and rebirth.