Dwarf Mistletoes Ecology and Management in the Rocky Mountain Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Santalales (Including Mistletoes)"

Santalales (Including Introductory article Mistletoes) Article Contents . Introduction Daniel L Nickrent, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, Illinois, USA . Taxonomy and Phylogenetics . Morphology, Life Cycle and Ecology . Biogeography of Mistletoes . Importance of Mistletoes Online posting date: 15th March 2011 Mistletoes are flowering plants in the sandalwood order that produce some of their own sugars via photosynthesis (Santalales) that parasitise tree branches. They evolved to holoparasites that do not photosynthesise. Holopar- five separate times in the order and are today represented asites are thus totally dependent on their host plant for by 88 genera and nearly 1600 species. Loranthaceae nutrients. Up until recently, all members of Santalales were considered hemiparasites. Molecular phylogenetic ana- (c. 1000 species) and Viscaceae (550 species) have the lyses have shown that the holoparasite family Balano- highest species diversity. In South America Misodendrum phoraceae is part of this order (Nickrent et al., 2005; (a parasite of Nothofagus) is the first to have evolved Barkman et al., 2007), however, its relationship to other the mistletoe habit ca. 80 million years ago. The family families is yet to be determined. See also: Nutrient Amphorogynaceae is of interest because some of its Acquisition, Assimilation and Utilization; Parasitism: the members are transitional between root and stem para- Variety of Parasites sites. Many mistletoes have developed mutualistic rela- The sandalwood order is of interest from the standpoint tionships with birds that act as both pollinators and seed of the evolution of parasitism because three early diverging dispersers. Although some mistletoes are serious patho- families (comprising 12 genera and 58 species) are auto- gens of forest and commercial trees (e.g. -

SYSTEMATICS of the MEGADIVERSE SUPERFAMILY GELECHIOIDEA (INSECTA: LEPIDOPTEA) DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of T

SYSTEMATICS OF THE MEGADIVERSE SUPERFAMILY GELECHIOIDEA (INSECTA: LEPIDOPTEA) DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sibyl Rae Bucheli, M.S. ***** The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Dr. John W. Wenzel, Advisor Dr. Daniel Herms Dr. Hans Klompen _________________________________ Dr. Steven C. Passoa Advisor Graduate Program in Entomology ABSTRACT The phylogenetics, systematics, taxonomy, and biology of Gelechioidea (Insecta: Lepidoptera) are investigated. This superfamily is probably the second largest in all of Lepidoptera, and it remains one of the least well known. Taxonomy of Gelechioidea has been unstable historically, and definitions vary at the family and subfamily levels. In Chapters Two and Three, I review the taxonomy of Gelechioidea and characters that have been important, with attention to what characters or terms were used by different authors. I revise the coding of characters that are already in the literature, and provide new data as well. Chapter Four provides the first phylogenetic analysis of Gelechioidea to include molecular data. I combine novel DNA sequence data from Cytochrome oxidase I and II with morphological matrices for exemplar species. The results challenge current concepts of Gelechioidea, suggesting that traditional morphological characters that have united taxa may not be homologous structures and are in need of further investigation. Resolution of this problem will require more detailed analysis and more thorough characterization of certain lineages. To begin this task, I conduct in Chapter Five an in- depth study of morphological evolution, host-plant selection, and geographical distribution of a medium-sized genus Depressaria Haworth (Depressariinae), larvae of ii which generally feed on plants in the families Asteraceae and Apiaceae. -

Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description

Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description Prepared by: Michael A. Kost, Dennis A. Albert, Joshua G. Cohen, Bradford S. Slaughter, Rebecca K. Schillo, Christopher R. Weber, and Kim A. Chapman Michigan Natural Features Inventory P.O. Box 13036 Lansing, MI 48901-3036 For: Michigan Department of Natural Resources Wildlife Division and Forest, Mineral and Fire Management Division September 30, 2007 Report Number 2007-21 Version 1.2 Last Updated: July 9, 2010 Suggested Citation: Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report Number 2007-21, Lansing, MI. 314 pp. Copyright 2007 Michigan State University Board of Trustees. Michigan State University Extension programs and materials are open to all without regard to race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, marital status or family status. Cover photos: Top left, Dry Sand Prairie at Indian Lake, Newaygo County (M. Kost); top right, Limestone Bedrock Lakeshore, Summer Island, Delta County (J. Cohen); lower left, Muskeg, Luce County (J. Cohen); and lower right, Mesic Northern Forest as a matrix natural community, Porcupine Mountains Wilderness State Park, Ontonagon County (M. Kost). Acknowledgements We thank the Michigan Department of Natural Resources Wildlife Division and Forest, Mineral, and Fire Management Division for funding this effort to classify and describe the natural communities of Michigan. This work relied heavily on data collected by many present and former Michigan Natural Features Inventory (MNFI) field scientists and collaborators, including members of the Michigan Natural Areas Council. -

Synthesizing Ecosystem Implications of Mistletoe Infection

Environmental Research Letters LETTER • OPEN ACCESS Related content - Networks on Networks: Water transport in Mistletoe, friend and foe: synthesizing ecosystem plants A G Hunt and S Manzoni implications of mistletoe infection - Networks on Networks: Edaphic constraints: the role of the soil in vegetation growth To cite this article: Anne Griebel et al 2017 Environ. Res. Lett. 12 115012 A G Hunt and S Manzoni - Impact of mountain pine beetle induced mortality on forest carbon and water fluxes David E Reed, Brent E Ewers and Elise Pendall View the article online for updates and enhancements. This content was downloaded from IP address 137.154.212.215 on 17/12/2017 at 21:57 Environ. Res. Lett. 12 (2017) 115012 https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa8fff LETTER Mistletoe, friend and foe: synthesizing ecosystem OPEN ACCESS implications of mistletoe infection RECEIVED 28 June 2017 Anne Griebel1,3 ,DavidWatson2 and Elise Pendall1 REVISED 1 Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment, Western Sydney University, Locked Bag 1797, Penrith, NSW, Australia 12 September 2017 2 Institute for Land, Water and Society, Charles Sturt University, PO box 789, Albury, NSW, Australia ACCEPTED FOR PUBLICATION 3 Author to whom any correspondence should be addressed. 29 September 2017 PUBLISHED E-mail: [email protected] 16 November 2017 Keywords: mistletoe, climate change, biodiversity, parasitic plants, tree mortality, forest disturbance Original content from this work may be used Abstract under the terms of the Creative Commons Biotic disturbances are affecting a wide range of tree species in all climates, and their occurrence is Attribution 3.0 licence. contributing to increasing rates of tree mortality globally. -

Working List of Prairie Restricted (Specialist) Insects in Wisconsin (11/26/2015)

Working List of Prairie Restricted (Specialist) Insects in Wisconsin (11/26/2015) By Richard Henderson Research Ecologist, WI DNR Bureau of Science Services Summary This is a preliminary list of insects that are either well known, or likely, to be closely associated with Wisconsin’s original native prairie. These species are mostly dependent upon remnants of original prairie, or plantings/restorations of prairie where their hosts have been re-established (see discussion below), and thus are rarely found outside of these settings. The list also includes some species tied to native ecosystems that grade into prairie, such as savannas, sand barrens, fens, sedge meadow, and shallow marsh. The list is annotated with known host(s) of each insect, and the likelihood of its presence in the state (see key at end of list for specifics). This working list is a byproduct of a prairie invertebrate study I coordinated from1995-2005 that covered 6 Midwestern states and included 14 cooperators. The project surveyed insects on prairie remnants and investigated the effects of fire on those insects. It was funded in part by a series of grants from the US Fish and Wildlife Service. So far, the list has 475 species. However, this is a partial list at best, representing approximately only ¼ of the prairie-specialist insects likely present in the region (see discussion below). Significant input to this list is needed, as there are major taxa groups missing or greatly under represented. Such absence is not necessarily due to few or no prairie-specialists in those groups, but due more to lack of knowledge about life histories (at least published knowledge), unsettled taxonomy, and lack of taxonomic specialists currently working in those groups. -

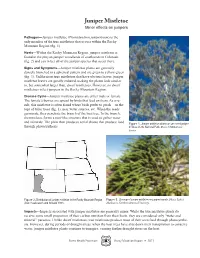

Juniper Mistletoe Minor Effects on Junipers

Juniper Mistletoe Minor effects on junipers Pathogen—Juniper mistletoe (Phoradendron juniperinum) is the only member of the true mistletoes that occurs within the Rocky Mountain Region (fig. 1). Hosts—Within the Rocky Mountain Region, juniper mistletoe is found in the pinyon-juniper woodlands of southwestern Colorado (fig. 2) and can infect all of the juniper species that occur there. Signs and Symptoms—Juniper mistletoe plants are generally densely branched in a spherical pattern and are green to yellow-green (fig. 3). Unlike most true mistletoes that have obvious leaves, juniper mistletoe leaves are greatly reduced, making the plants look similar to, but somewhat larger than, dwarf mistletoes. However, no dwarf mistletoes infect junipers in the Rocky Mountain Region. Disease Cycle—Juniper mistletoe plants are either male or female. The female’s berries are spread by birds that feed on them. As a re- sult, this mistletoe is often found where birds prefer to perch—on the tops of taller trees (fig. 1), near water sources, etc. When the seeds germinate, they penetrate the branch of the host tree. In the branch, the mistletoe forms a root-like structure that is used to gather water and minerals. The plant then produces aerial shoots that produce food Figure 1. Juniper mistletoe plants on one-seed juniper through photosynthesis. in Mesa Verde National Park. Photo: USDA Forest Service. Figure 2. Distribution of juniper mistletoe in the Rocky Mountain Region Figure 3. Closeup of juniper mistletoe on juniper branch. Photo: Robert (from Hawksworth and Scharpf 1981). Mathiasen, Northern Arizona University. Impacts—Impacts associated with juniper mistletoe are generally minor. -

Lodgepole Pine Dwarf Mistletoe in Taylor Park, Colorado Report for the Taylor Park Environmental Assessment

Lodgepole Pine Dwarf Mistletoe in Taylor Park, Colorado Report for the Taylor Park Environmental Assessment Jim Worrall, Ph.D. Gunnison Service Center Forest Health Protection Rocky Mountain Region USDA Forest Service 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 2 2. DESCRIPTION, DISTRIBUTION, HOSTS ..................................................................................... 2 3. LIFE CYCLE....................................................................................................................................... 3 4. SCOPE OF TREATMENTS RELATIVE TO INFESTED AREA ................................................. 4 5. IMPACTS ON TREES AND FORESTS ........................................................................................... 4 5.1 TREE GROWTH AND LONGEVITY .................................................................................................... 4 5.2 EFFECTS OF DWARF MISTLETOE ON FOREST DYNAMICS ............................................................... 6 5.3 RATE OF SPREAD AND INTENSIFICATION ........................................................................................ 6 6. IMPACTS OF DWARF MISTLETOES ON ANIMALS ................................................................ 6 6.1 DIVERSITY AND ABUNDANCE OF VERTEBRATES ............................................................................ 7 6.2 EFFECT OF MISTLETOE-CAUSED SNAGS ON VERTEBRATES ............................................................12 -

Dwarf Mistletoes: Biology, Pathology, and Systematics

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. CHAPTER 10 Anatomy of the Dwarf Mistletoe Shoot System Carol A. Wilson and Clyde L. Calvin * In this chapter, we present an overview of the Morphology of Shoots structure of the Arceuthobium shoot system. Anatomical examination reveals that dwarf mistletoes Arceuthobium does not produce shoots immedi are indeed well adapted to a parasitic habit. An exten ately after germination. The endophytic system first sive endophytic system (see chapter 11) interacts develops within the host branch. Oftentimes, the only physiologically with the host to obtain needed evidence of infection is swelling of the tissues near the resources (water, minerals, and photosynthates); and infection site (Scharpf 1967). After 1 to 3 years, the first the shoots provide regulatory and reproductive func shoots are produced (table 2.1). All shoots arise from tions. Beyond specialization of their morphology (Le., the endophytic system and thus are root-borne shoots their leaves are reduced to scales), the dwarf mistle (Groff and Kaplan 1988). In emerging shoots, the toes also show peculiarities of their structure that leaves of adjacent nodes overlap and conceal the stem. reflect their phylogenetic relationships with other As the internodes elongate, stem segments become mistletoes and illustrate a high degree of specialization visible; but the shoot apex remains tightly enclosed by for the parasitic habit. From Arceuthobium globosum, newly developing leaf primordia (fig. 10.lA). Two the largest described species with shoots 70 cm tall oppositely arranged leaves, joined at their bases, occur and 5 cm in diameter, toA. -

Mistletoes: Pathogens, Keystone Resource, and Medicinal Wonder Abstracts

Mistletoes: Pathogens, Keystone Resource, and Medicinal Wonder Abstracts Oral Presentations Phylogenetic relationships in Phoradendron (Viscaceae) Vanessa Ashworth, Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden Keywords: Phoradendron, Systematics, Phylogenetics Phoradendron Nutt. is a genus of New World mistletoes comprising ca. 240 species distributed from the USA to Argentina and including the Antillean islands. Taxonomic treatments based on morphology have been hampered by phenotypic plasticity, size reduction of floral parts, and a shortage of taxonomically useful traits. Morphological characters used to differentiate species include the arrangement of flowers on an inflorescence segment (seriation) and the presence/absence and pattern of insertion of cataphylls on the stem. The only trait distinguishing Phoradendron from Dendrophthora Eichler, another New World mistletoe genus with a tropical distribution contained entirely within that of Phoradendron, is the number of anther locules. However, several lines of evidence suggest that neither Phoradendron nor Dendrophthora is monophyletic, although together they form the strongly supported monophyletic tribe Phoradendreae of nearly 360 species. To date, efforts to delineate supraspecific assemblages have been largely unsuccessful, and the only attempt to apply molecular sequence data dates back 16 years. Insights gleaned from that study, which used the ITS region and two partitions of the 26S nuclear rDNA, will be discussed, and new information pertinent to the systematics and biology of Phoradendron will be reviewed. The Viscaceae, why so successful? Clyde Calvin, University of California, Berkeley Carol A. Wilson, The University and Jepson Herbaria, University of California, Berkeley Keywords: Endophytic system, Epicortical roots, Epiparasite Mistletoe is the term used to describe aerial-branch parasites belonging to the order Santalales. -

Conspecific Pollen on Insects Visiting Female Flowers of Phoradendron Juniperinum (Viscaceae) in Western Arizona

Western North American Naturalist Volume 77 Number 4 Article 7 1-16-2017 Conspecific pollen on insects visiting emalef flowers of Phoradendron juniperinum (Viscaceae) in western Arizona William D. Wiesenborn [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan Recommended Citation Wiesenborn, William D. (2017) "Conspecific pollen on insects visiting emalef flowers of Phoradendron juniperinum (Viscaceae) in western Arizona," Western North American Naturalist: Vol. 77 : No. 4 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan/vol77/iss4/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Western North American Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Western North American Naturalist 77(4), © 2017, pp. 478–486 CONSPECIFIC POLLEN ON INSECTS VISITING FEMALE FLOWERS OF PHORADENDRON JUNIPERINUM (VISCACEAE) IN WESTERN ARIZONA William D. Wiesenborn1 ABSTRACT.—Phoradendron juniperinum (Viscaceae) is a dioecious, parasitic plant of juniper trees ( Juniperus [Cupressaceae]) that occurs from eastern California to New Mexico and into northern Mexico. The species produces minute, spherical flowers during early summer. Dioecious flowering requires pollinating insects to carry pollen from male to female plants. I investigated the pollination of P. juniperinum parasitizing Juniperus osteosperma trees in the Cerbat Mountains in western Arizona during June–July 2016. I examined pollen from male flowers, aspirated insects from female flowers, counted conspecific pollen grains on insects, and estimated floral constancy from proportions of conspecific pollen in pollen loads. -

Lodgepole Pine Dwarf Mistletoe Common Cause of Brooming in Lodgepole Pine

Lodgepole Pine Dwarf Mistletoe Common cause of brooming in lodgepole pine Pathogen—Lodgepole pine dwarf mistletoe (Arceuthobium americanum) is the most widely distributed, one of the most damag- ing, and one of the best studied dwarf mistletoes in North America. Aerial shoots are yellowish to olive green, 2-3 1/2 inches (5-9 cm) long (maximum 12 inches [30 cm]) and up to 1/25-1/8 inch (1-3 mm) diameter (figs. 1-2). The distribution generally follows that of its principal host, lodgepole pine, in the Rocky Mountain Region (fig. 3). Hosts—Lodgepole pine dwarf mistletoe infects primarily its namesake, but ponderosa pine is considered a secondary host of this species. However, lodgepole pine dwarf mistletoe can sustain itself and even be aggressive in pure stands of Rocky Mountain ponderosa pine in northern Colorado and southern Wyoming sometimes a mile or more away from infected lodgepole pine. This infection generally occurs in areas outside the range of ponderosa pine’s usual parasite, southwestern dwarf mistletoe. Figure 1. Flowering male lodgepole pine dwarf mistletow plant para- Figure 2. Female lodgepole pine dwarf mistletoe plant with imma- sitizing lodgepole pine. Photo: Brian Howell, USDA Forest Service. ture fruit parasitizing lodgepole pine. Note the basal cups left behind where old shoots have fallen off. Photo: Brian Howell, USDA Forest Service. Signs and Symptoms—Signs of infection are shoots and basal cups (fig. 2) found at infection sites. Symptoms include witches’ brooms, swelling of in- fected branches, and dieback. Lodgepole pine dwarf mistletoe infections grow systemically with the branches they infect, sometimes causing large witches’ brooms with elongated, loosely hanging branches. -

Researchcommons.Waikato.Ac.Nz

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Commons@Waikato http://researchcommons.waikato.ac.nz/ Research Commons at the University of Waikato Copyright Statement: The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). The thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognise the author’s right to be identified as the author of the thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. You will obtain the author’s permission before publishing any material from the thesis. Identifying Host Species of Dactylanthus taylorii using DNA Barcoding A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Science in Biological Sciences at The University of Waikato by Cassarndra Marie Parker _________ The University of Waikato 2015 Acknowledgements: This thesis wouldn't have been possible without the support of many people. Firstly, my supervisors Dr Chrissen Gemmill and Dr Avi Holzapfel - your professional expertise, advice, and patience were invaluable. From pitching the idea in 2012 to reading through drafts in the final fortnight, I've been humbled to work with such dedicated and accomplished scientists. Special mention also goes to Thomas Emmitt, David Mudge, Steven Miller, the Auckland Zoo horticulture team and Kevin.