Overwintering Hosts for the Exotic Leafroller

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SYSTEMATICS of the MEGADIVERSE SUPERFAMILY GELECHIOIDEA (INSECTA: LEPIDOPTEA) DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of T

SYSTEMATICS OF THE MEGADIVERSE SUPERFAMILY GELECHIOIDEA (INSECTA: LEPIDOPTEA) DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sibyl Rae Bucheli, M.S. ***** The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Dr. John W. Wenzel, Advisor Dr. Daniel Herms Dr. Hans Klompen _________________________________ Dr. Steven C. Passoa Advisor Graduate Program in Entomology ABSTRACT The phylogenetics, systematics, taxonomy, and biology of Gelechioidea (Insecta: Lepidoptera) are investigated. This superfamily is probably the second largest in all of Lepidoptera, and it remains one of the least well known. Taxonomy of Gelechioidea has been unstable historically, and definitions vary at the family and subfamily levels. In Chapters Two and Three, I review the taxonomy of Gelechioidea and characters that have been important, with attention to what characters or terms were used by different authors. I revise the coding of characters that are already in the literature, and provide new data as well. Chapter Four provides the first phylogenetic analysis of Gelechioidea to include molecular data. I combine novel DNA sequence data from Cytochrome oxidase I and II with morphological matrices for exemplar species. The results challenge current concepts of Gelechioidea, suggesting that traditional morphological characters that have united taxa may not be homologous structures and are in need of further investigation. Resolution of this problem will require more detailed analysis and more thorough characterization of certain lineages. To begin this task, I conduct in Chapter Five an in- depth study of morphological evolution, host-plant selection, and geographical distribution of a medium-sized genus Depressaria Haworth (Depressariinae), larvae of ii which generally feed on plants in the families Asteraceae and Apiaceae. -

Micro-Moth Grading Guidelines (Scotland) Abhnumber Code

Micro-moth Grading Guidelines (Scotland) Scottish Adult Mine Case ABHNumber Code Species Vernacular List Grade Grade Grade Comment 1.001 1 Micropterix tunbergella 1 1.002 2 Micropterix mansuetella Yes 1 1.003 3 Micropterix aureatella Yes 1 1.004 4 Micropterix aruncella Yes 2 1.005 5 Micropterix calthella Yes 2 2.001 6 Dyseriocrania subpurpurella Yes 2 A Confusion with fly mines 2.002 7 Paracrania chrysolepidella 3 A 2.003 8 Eriocrania unimaculella Yes 2 R Easier if larva present 2.004 9 Eriocrania sparrmannella Yes 2 A 2.005 10 Eriocrania salopiella Yes 2 R Easier if larva present 2.006 11 Eriocrania cicatricella Yes 4 R Easier if larva present 2.007 13 Eriocrania semipurpurella Yes 4 R Easier if larva present 2.008 12 Eriocrania sangii Yes 4 R Easier if larva present 4.001 118 Enteucha acetosae 0 A 4.002 116 Stigmella lapponica 0 L 4.003 117 Stigmella confusella 0 L 4.004 90 Stigmella tiliae 0 A 4.005 110 Stigmella betulicola 0 L 4.006 113 Stigmella sakhalinella 0 L 4.007 112 Stigmella luteella 0 L 4.008 114 Stigmella glutinosae 0 L Examination of larva essential 4.009 115 Stigmella alnetella 0 L Examination of larva essential 4.010 111 Stigmella microtheriella Yes 0 L 4.011 109 Stigmella prunetorum 0 L 4.012 102 Stigmella aceris 0 A 4.013 97 Stigmella malella Apple Pigmy 0 L 4.014 98 Stigmella catharticella 0 A 4.015 92 Stigmella anomalella Rose Leaf Miner 0 L 4.016 94 Stigmella spinosissimae 0 R 4.017 93 Stigmella centifoliella 0 R 4.018 80 Stigmella ulmivora 0 L Exit-hole must be shown or larval colour 4.019 95 Stigmella viscerella -

State of New York City's Plants 2018

STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 Daniel Atha & Brian Boom © 2018 The New York Botanical Garden All rights reserved ISBN 978-0-89327-955-4 Center for Conservation Strategy The New York Botanical Garden 2900 Southern Boulevard Bronx, NY 10458 All photos NYBG staff Citation: Atha, D. and B. Boom. 2018. State of New York City’s Plants 2018. Center for Conservation Strategy. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY. 132 pp. STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 INTRODUCTION 10 DOCUMENTING THE CITY’S PLANTS 10 The Flora of New York City 11 Rare Species 14 Focus on Specific Area 16 Botanical Spectacle: Summer Snow 18 CITIZEN SCIENCE 20 THREATS TO THE CITY’S PLANTS 24 NEW YORK STATE PROHIBITED AND REGULATED INVASIVE SPECIES FOUND IN NEW YORK CITY 26 LOOKING AHEAD 27 CONTRIBUTORS AND ACKNOWLEGMENTS 30 LITERATURE CITED 31 APPENDIX Checklist of the Spontaneous Vascular Plants of New York City 32 Ferns and Fern Allies 35 Gymnosperms 36 Nymphaeales and Magnoliids 37 Monocots 67 Dicots 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report, State of New York City’s Plants 2018, is the first rankings of rare, threatened, endangered, and extinct species of what is envisioned by the Center for Conservation Strategy known from New York City, and based on this compilation of The New York Botanical Garden as annual updates thirteen percent of the City’s flora is imperiled or extinct in New summarizing the status of the spontaneous plant species of the York City. five boroughs of New York City. This year’s report deals with the City’s vascular plants (ferns and fern allies, gymnosperms, We have begun the process of assessing conservation status and flowering plants), but in the future it is planned to phase in at the local level for all species. -

Working List of Prairie Restricted (Specialist) Insects in Wisconsin (11/26/2015)

Working List of Prairie Restricted (Specialist) Insects in Wisconsin (11/26/2015) By Richard Henderson Research Ecologist, WI DNR Bureau of Science Services Summary This is a preliminary list of insects that are either well known, or likely, to be closely associated with Wisconsin’s original native prairie. These species are mostly dependent upon remnants of original prairie, or plantings/restorations of prairie where their hosts have been re-established (see discussion below), and thus are rarely found outside of these settings. The list also includes some species tied to native ecosystems that grade into prairie, such as savannas, sand barrens, fens, sedge meadow, and shallow marsh. The list is annotated with known host(s) of each insect, and the likelihood of its presence in the state (see key at end of list for specifics). This working list is a byproduct of a prairie invertebrate study I coordinated from1995-2005 that covered 6 Midwestern states and included 14 cooperators. The project surveyed insects on prairie remnants and investigated the effects of fire on those insects. It was funded in part by a series of grants from the US Fish and Wildlife Service. So far, the list has 475 species. However, this is a partial list at best, representing approximately only ¼ of the prairie-specialist insects likely present in the region (see discussion below). Significant input to this list is needed, as there are major taxa groups missing or greatly under represented. Such absence is not necessarily due to few or no prairie-specialists in those groups, but due more to lack of knowledge about life histories (at least published knowledge), unsettled taxonomy, and lack of taxonomic specialists currently working in those groups. -

Habitat Guidelines for Mule Deer: California Woodland Chaparral Ecoregion

THE AUTHORS : MARY L. SOMMER CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME WILDLIFE BRANCH 1812 NINTH STREET SACRAMENTO, CA 95814 REBECCA L. BARBOZA CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME SOUTH COAST REGION 4665 LAMPSON AVENUE, SUITE C LOS ALAMITOS, CA 90720 RANDY A. BOTTA CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME SOUTH COAST REGION 4949 VIEWRIDGE AVENUE SAN DIEGO, CA 92123 ERIC B. KLEINFELTER CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME CENTRAL REGION 1234 EAST SHAW AVENUE FRESNO, CA 93710 MARTHA E. SCHAUSS CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME CENTRAL REGION 1234 EAST SHAW AVENUE FRESNO, CA 93710 J. ROCKY THOMPSON CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME CENTRAL REGION P.O. BOX 2330 LAKE ISABELLA, CA 93240 Cover photo by: California Department of Fish and Game (CDFG) Suggested Citation: Sommer, M. L., R. L. Barboza, R. A. Botta, E. B. Kleinfelter, M. E. Schauss and J. R. Thompson. 2007. Habitat Guidelines for Mule Deer: California Woodland Chaparral Ecoregion. Mule Deer Working Group, Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 2 THE CALIFORNIA WOODLAND CHAPARRAL ECOREGION 4 Description 4 Ecoregion-specific Deer Ecology 4 MAJOR IMPACTS TO MULE DEER HABITAT 6 IN THE CALIFORNIA WOODLAND CHAPARRA L CONTRIBUTING FACTORS AND SPECIFIC 7 HABITAT GUIDELINES Long-term Fire Suppression 7 Human Encroachment 13 Wild and Domestic Herbivores 18 Water Availability and Hydrological Changes 26 Non-native Invasive Species 30 SUMMARY 37 LITERATURE CITED 38 APPENDICIES 46 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ule and black-tailed deer (collectively called Forest is severe winterkill. Winterkill is not a mule deer, Odocoileus hemionus ) are icons of problem in the Southwest Deserts, but heavy grazing the American West. -

Lepidoptera: Tortricidae: Tortricinae) and Evolutionary Correlates of Novel Secondary Sexual Structures

Zootaxa 3729 (1): 001–062 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Monograph ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2013 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3729.1.1 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:CA0C1355-FF3E-4C67-8F48-544B2166AF2A ZOOTAXA 3729 Phylogeny of the tribe Archipini (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae: Tortricinae) and evolutionary correlates of novel secondary sexual structures JASON J. DOMBROSKIE1,2,3 & FELIX A. H. SPERLING2 1Cornell University, Comstock Hall, Department of Entomology, Ithaca, NY, USA, 14853-2601. E-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada, T6G 2E9 3Corresponding author Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand Accepted by J. Brown: 2 Sept. 2013; published: 25 Oct. 2013 Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0 JASON J. DOMBROSKIE & FELIX A. H. SPERLING Phylogeny of the tribe Archipini (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae: Tortricinae) and evolutionary correlates of novel secondary sexual structures (Zootaxa 3729) 62 pp.; 30 cm. 25 Oct. 2013 ISBN 978-1-77557-288-6 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-77557-289-3 (Online edition) FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2013 BY Magnolia Press P.O. Box 41-383 Auckland 1346 New Zealand e-mail: [email protected] http://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ © 2013 Magnolia Press 2 · Zootaxa 3729 (1) © 2013 Magnolia Press DOMBROSKIE & SPERLING Table of contents Abstract . 3 Material and methods . 6 Results . 18 Discussion . 23 Conclusions . 33 Acknowledgements . 33 Literature cited . 34 APPENDIX 1. 38 APPENDIX 2. 44 Additional References for Appendices 1 & 2 . 49 APPENDIX 3. 51 APPENDIX 4. 52 APPENDIX 5. -

Rare Plant Survey of San Juan Public Lands, Colorado

Rare Plant Survey of San Juan Public Lands, Colorado 2005 Prepared by Colorado Natural Heritage Program 254 General Services Building Colorado State University Fort Collins CO 80523 Rare Plant Survey of San Juan Public Lands, Colorado 2005 Prepared by Peggy Lyon and Julia Hanson Colorado Natural Heritage Program 254 General Services Building Colorado State University Fort Collins CO 80523 December 2005 Cover: Imperiled (G1 and G2) plants of the San Juan Public Lands, top left to bottom right: Lesquerella pruinosa, Draba graminea, Cryptantha gypsophila, Machaeranthera coloradoensis, Astragalus naturitensis, Physaria pulvinata, Ipomopsis polyantha, Townsendia glabella, Townsendia rothrockii. Executive Summary This survey was a continuation of several years of rare plant survey on San Juan Public Lands. Funding for the project was provided by San Juan National Forest and the San Juan Resource Area of the Bureau of Land Management. Previous rare plant surveys on San Juan Public Lands by CNHP were conducted in conjunction with county wide surveys of La Plata, Archuleta, San Juan and San Miguel counties, with partial funding from Great Outdoors Colorado (GOCO); and in 2004, public lands only in Dolores and Montezuma counties, funded entirely by the San Juan Public Lands. Funding for 2005 was again provided by San Juan Public Lands. The primary emphases for field work in 2005 were: 1. revisit and update information on rare plant occurrences of agency sensitive species in the Colorado Natural Heritage Program (CNHP) database that were last observed prior to 2000, in order to have the most current information available for informing the revision of the Resource Management Plan for the San Juan Public Lands (BLM and San Juan National Forest); 2. -

Additions, Deletions and Corrections to An

Bulletin of the Irish Biogeographical Society No. 36 (2012) ADDITIONS, DELETIONS AND CORRECTIONS TO AN ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE IRISH BUTTERFLIES AND MOTHS (LEPIDOPTERA) WITH A CONCISE CHECKLIST OF IRISH SPECIES AND ELACHISTA BIATOMELLA (STAINTON, 1848) NEW TO IRELAND K. G. M. Bond1 and J. P. O’Connor2 1Department of Zoology and Animal Ecology, School of BEES, University College Cork, Distillery Fields, North Mall, Cork, Ireland. e-mail: <[email protected]> 2Emeritus Entomologist, National Museum of Ireland, Kildare Street, Dublin 2, Ireland. Abstract Additions, deletions and corrections are made to the Irish checklist of butterflies and moths (Lepidoptera). Elachista biatomella (Stainton, 1848) is added to the Irish list. The total number of confirmed Irish species of Lepidoptera now stands at 1480. Key words: Lepidoptera, additions, deletions, corrections, Irish list, Elachista biatomella Introduction Bond, Nash and O’Connor (2006) provided a checklist of the Irish Lepidoptera. Since its publication, many new discoveries have been made and are reported here. In addition, several deletions have been made. A concise and updated checklist is provided. The following abbreviations are used in the text: BM(NH) – The Natural History Museum, London; NMINH – National Museum of Ireland, Natural History, Dublin. The total number of confirmed Irish species now stands at 1480, an addition of 68 since Bond et al. (2006). Taxonomic arrangement As a result of recent systematic research, it has been necessary to replace the arrangement familiar to British and Irish Lepidopterists by the Fauna Europaea [FE] system used by Karsholt 60 Bulletin of the Irish Biogeographical Society No. 36 (2012) and Razowski, which is widely used in continental Europe. -

Native Plant List CITY of OREGON CITY 320 Warner Milne Road , P.O

Native Plant List CITY OF OREGON CITY 320 Warner Milne Road , P.O. Box 3040, Oregon City, OR 97045 Phone: (503) 657-0891, Fax: (503) 657-7892 Scientific Name Common Name Habitat Type Wetland Riparian Forest Oak F. Slope Thicket Grass Rocky Wood TREES AND ARBORESCENT SHRUBS Abies grandis Grand Fir X X X X Acer circinatumAS Vine Maple X X X Acer macrophyllum Big-Leaf Maple X X Alnus rubra Red Alder X X X Alnus sinuata Sitka Alder X Arbutus menziesii Madrone X Cornus nuttallii Western Flowering XX Dogwood Cornus sericia ssp. sericea Crataegus douglasii var. Black Hawthorn (wetland XX douglasii form) Crataegus suksdorfii Black Hawthorn (upland XXX XX form) Fraxinus latifolia Oregon Ash X X Holodiscus discolor Oceanspray Malus fuscaAS Western Crabapple X X X Pinus ponderosa Ponderosa Pine X X Populus balsamifera ssp. Black Cottonwood X X Trichocarpa Populus tremuloides Quaking Aspen X X Prunus emarginata Bitter Cherry X X X Prunus virginianaAS Common Chokecherry X X X Pseudotsuga menziesii Douglas Fir X X Pyrus (see Malus) Quercus garryana Garry Oak X X X Quercus garryana Oregon White Oak Rhamnus purshiana Cascara X X X Salix fluviatilisAS Columbia River Willow X X Salix geyeriana Geyer Willow X Salix hookerianaAS Piper's Willow X X Salix lucida ssp. lasiandra Pacific Willow X X Salix rigida var. macrogemma Rigid Willow X X Salix scouleriana Scouler Willow X X X Salix sessilifoliaAS Soft-Leafed Willow X X Salix sitchensisAS Sitka Willow X X Salix spp.* Willows Sambucus spp.* Elderberries Spiraea douglasii Douglas's Spiraea Taxus brevifolia Pacific Yew X X X Thuja plicata Western Red Cedar X X X X Tsuga heterophylla Western Hemlock X X X Scientific Name Common Name Habitat Type Wetland Riparian Forest Oak F. -

They Come in Teams

GBE Frankia-Enriched Metagenomes from the Earliest Diverging Symbiotic Frankia Cluster: They Come in Teams Thanh Van Nguyen1, Daniel Wibberg2, Theoden Vigil-Stenman1,FedeBerckx1, Kai Battenberg3, Kirill N. Demchenko4,5, Jochen Blom6, Maria P. Fernandez7, Takashi Yamanaka8, Alison M. Berry3, Jo¨ rn Kalinowski2, Andreas Brachmann9, and Katharina Pawlowski 1,* 1Department of Ecology, Environment and Plant Sciences, Stockholm University, Sweden 2Center for Biotechnology (CeBiTec), Bielefeld University, Germany 3Department of Plant Sciences, University of California, Davis 4Laboratory of Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Plant Development, Komarov Botanical Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, Saint Petersburg, Russia 5Laboratory of Molecular and Cellular Biology, All-Russia Research Institute for Agricultural Microbiology, Saint Petersburg, Russia 6Bioinformatics and Systems Biology, Justus Liebig University, Gießen, Germany 7Ecologie Microbienne, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique UMR 5557, Universite Lyon I, Villeurbanne Cedex, France 8Forest and Forestry Products Research Institute, Ibaraki, Japan 9Biocenter, Ludwig Maximilians University Munich, Planegg-Martinsried, Germany *Corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected]. Accepted: July 10, 2019 Data deposition: This project has been deposited at EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ under the accession PRJEB19438 - PRJEB19449. Abstract Frankia strains induce the formation of nitrogen-fixing nodules on roots of actinorhizal plants. Phylogenetically, Frankia strains can be grouped in four clusters. The earliest divergent cluster, cluster-2, has a particularly wide host range. The analysis of cluster-2 strains has been hampered by the fact that with two exceptions, they could never be cultured. In this study, 12 Frankia-enriched meta- genomes of Frankia cluster-2 strains or strain assemblages were sequenced based on seven inoculum sources. Sequences obtained via DNA isolated from whole nodules were compared with those of DNA isolated from fractionated preparations enhanced in the Frankia symbiotic structures. -

Native Shrubs

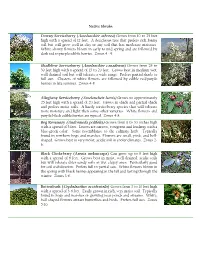

Native Shrubs Downy Serviceberry (Amelanchier arborea) Grows from 10 to 25 feet high with a spread of 12 feet. A deciduous tree that prefers rich loamy soil but will grow well in clay or any soil that has moderate moisture. White showy flowers bloom in early to mid spring and are followed by dark red to purple edible berries. Zones 4 - 9. Shadblow Serviceberry (Amelanchier canadensis) Grows from 25 to 30 feet high with a spread of 15 to 20 feet. Grows best in medium wet, well-drained soil but will tolerate a wide range. Prefers partial shade to full sun. Clusters of white flowers are followed by edible red/purple berries in late summer. Zones 4-8 Allegheny Serviceberry (Amelancheir laevis) Grows to approximately 25 feet high with a spread of 20 feet. Grows in shade and partial shade and prefers moist soils. A hardy serviceberry species that will tolerate more moisture and light then some other varieties. White flowers and purple/black edible berries are typical. Zones 4-8. Bog Rosemary (Andromeda polifolia) Grows from 6 to 30 inches high with a spread of 3 feet. Leaves are narrow, evergreen and leathery with a blue-green color. Some resemblance to the culinary herb. Typically found in northern bogs and marshes. Flowers are small, pink, and bell- shaped. Grows best in very moist, acidic soil in cooler climates. Zones 2- 6. Black Chokeberry (Aronia melancarpa) Can grow up to 8 feet high with a spread of 8 feet. Grows best in moist, well-drained, acidic soils but will tolerate drier sandy soils or wet clayey ones. -

List of Plants for Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve

Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve Plant Checklist DRAFT as of 29 November 2005 FERNS AND FERN ALLIES Equisetaceae (Horsetail Family) Vascular Plant Equisetales Equisetaceae Equisetum arvense Present in Park Rare Native Field horsetail Vascular Plant Equisetales Equisetaceae Equisetum laevigatum Present in Park Unknown Native Scouring-rush Polypodiaceae (Fern Family) Vascular Plant Polypodiales Dryopteridaceae Cystopteris fragilis Present in Park Uncommon Native Brittle bladderfern Vascular Plant Polypodiales Dryopteridaceae Woodsia oregana Present in Park Uncommon Native Oregon woodsia Pteridaceae (Maidenhair Fern Family) Vascular Plant Polypodiales Pteridaceae Argyrochosma fendleri Present in Park Unknown Native Zigzag fern Vascular Plant Polypodiales Pteridaceae Cheilanthes feei Present in Park Uncommon Native Slender lip fern Vascular Plant Polypodiales Pteridaceae Cryptogramma acrostichoides Present in Park Unknown Native American rockbrake Selaginellaceae (Spikemoss Family) Vascular Plant Selaginellales Selaginellaceae Selaginella densa Present in Park Rare Native Lesser spikemoss Vascular Plant Selaginellales Selaginellaceae Selaginella weatherbiana Present in Park Unknown Native Weatherby's clubmoss CONIFERS Cupressaceae (Cypress family) Vascular Plant Pinales Cupressaceae Juniperus scopulorum Present in Park Unknown Native Rocky Mountain juniper Pinaceae (Pine Family) Vascular Plant Pinales Pinaceae Abies concolor var. concolor Present in Park Rare Native White fir Vascular Plant Pinales Pinaceae Abies lasiocarpa Present