Transportation Policymaking in Beijing and Shanghai: Contributors, Obstacles and Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Remote Sensing Analysis of the Status of the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal

REMOTE SENSING ANALYSIS OF THE STATUS OF THE BEIJING-HANGZHOU GRAND CANAL B. Deng H. Guo , C. Wang , Y. Nie, The Institute of Remote Sensing Applications, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China - [email protected] Commission VI, WG V/2 KEY WORDS: Image interpretation, Image understanding, Feature detection, Archaeology ABSTRACT: Remote sensing began with the use of aerial photography and is acknowledged as a valuable tool for viewing, analyzing, characterizing, and making decisions about our environment. The Grand Canal of China is the longest ancient canal in the world and recently approved as the Key National Relics-preservation Unit. In our work multi-source and multi-temporal remote sensing data, including the aerial photographs taken half a century ago and the recently acquired SPOT5 multispectral images and the RADARSAT-1 images are collected. Through a comparative and complementary analysis of the data sets, some findings are given. The general characteristics of the canal course and the canal cities are also described, which provides important information for the making plans of the Grand Canal preservation. 1. INTRODUCTION can provide radar images at the spatial resolution of 1 meter. The fourth advantage is the high spectral resolution. Now the Remote sensing, in the broadest sense, is the short or large-scale hyperspectral sensor can acquire image at hundreds of channels acquisition of information of an object or phenomenon, by the simultaneously, which can grasp the small changes of use of either recording or real-time sensing device(s) that is not reflectance and make possible the discrimination of some in physical or intimate contact with the object (such as by way targets. -

Trends in China Facts from the Renewables in Cities 2021 Global Status Report

Embargoed until: 09:30 CET Paris Time – 18 March 2021 Trends in China Facts from the Renewables in Cities 2021 Global Status Report Key Renewable Energy Takeaways in 2020 from China • China is the greatest market in the world for solar PV1, with many of these developments taking place in urban areas and helping to decarbonise energy use in buildings; however, further efforts are needed to increase the share of renewables across sectors, including heating and cooling, but also power – especially in light of the expansion of e-mobility2. • The electrification of all transport modes has been pioneered in Chinese cities; they are visibly committed to the national EV ambition, providing complementary municipal-level subsidies (in addition to national incentives) for battery electric and fuel cell electric vehicles. • China is the second-largest producer of district heating (DH) in the world, and although these systems rely almost entirely on fossil fuels, some cities have been increasing solar thermal and geothermal heating capacity and use in their DH networks. Brand new data shows • Only 25 cities had renewable energy targets and/or policies from a global total of over 1,300 cities). This covers 321 million people, 38% of the urban population in China • On a global scale, Chinese cities are lagging behind on setting net-zero3 targets: some notable exceptions exist: 6 cities were developing net-zero targets in 2020, and Dalian set a target to achieve net-zero by 2050. Rizhao has had a target for climate neutrality by 2050 since 2008. Renewable Energy Developments in Chinese Cities City renewable energy commitments and policies • Most city-level targets and actions are in line with (and often part of the implementation of) national-level policy, including China’s commitment to reach carbon neutrality by 2060. -

China-Singapore Jilin Food Zone Project Signed in Beijing

About Home News Topic Leadership Government Investment Travel Living Community Jilin Home>Topic>Special Report>The Eighth Northeast Asia Expo T T T Special Report China-Singapore Jilin Food Zone project signed in Beijing read_image.jpg Travel Guide On the afternoon of September 6, the China-Singapore Jilin Food Zone project signing ceremony was held in the Great Hall of the People in Beijing. Premier Wen Jiabao and Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong attended the signing ceremony. Governor Wang Rulin and President of Singapore Temasek Holdings Kohl signed the Framework Agreement on Cooperation in Multiple Fields. Leaders from Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Development and Reform Comm ission, the Ministry of Commerce, the Ministry of Housing and Urban and Rural Const ruction, and Singapore Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of National Development Cooperation , Ministry of Trade and Industry and other ministries and other leaders from the minis Laws & tries of the two countries, as well as Chief Executive of Singapore Temasek Holdings Regulations Ho Ching, Chairman of Singapore Starbridge Holdings (Private) Limited Wong Kan Se Business Help ng, Singapore Temasek Holdings Consultant and Keppel Group Chairman Lee Boon Ya Festival Exhibition ng, Singapore Starbridge Holdings (Private) Limited CE0 Chong Phit Lian and other Si ngapore enterprise executives attended the ceremony. According to the Framework Agreement on Cooperation in Multiple Fields, China and Singapore will achieve comprehensive cooperation in various fields -

Low Carbon Development Roadmap for Jilin City Jilin for Roadmap Development Carbon Low Roadmap for Jilin City

Low Carbon Development Low Carbon Development Roadmap for Jilin City Roadmap for Jilin City Chatham House, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Energy Research Institute, Jilin University, E3G March 2010 Chatham House, 10 St James Square, London SW1Y 4LE T: +44 (0)20 7957 5700 E: [email protected] F: +44 (0)20 7957 5710 www.chathamhouse.org.uk Charity Registration Number: 208223 Low Carbon Development Roadmap for Jilin City Chatham House, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Energy Research Institute, Jilin University, E3G March 2010 © Royal Institute of International Affairs, 2010 Chatham House (the Royal Institute of International Affairs) is an independent body which promotes the rigorous study of international questions and does not express opinion of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are the responsibility of the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the copyright holder. Please direct all enquiries to the publishers. Chatham House 10 St James’s Square London, SW1Y 4LE T: +44 (0) 20 7957 5700 F: +44 (0) 20 7957 5710 www.chathamhouse.org.uk Charity Registration No. 208223 ISBN 978 1 86203 230 9 A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. Cover image: factory on the Songhua River, Jilin. Reproduced with kind permission from original photo, © Christian Als, -

The Regeneration of Millennium Ancient City by Beijing-Hangzhou

TANG LEI, QIU JIANJUN, ‘FLOWING’: The Regeneration of Millennium ancient city , 47 th ISOCARP Congress 2011 ‘FLOWING’: The Regeneration of Millennium ancient city by Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal ——Practice in Suqian, Jiangsu, China 1 The Millennium ancient city - Suqian Overview 1.1 City Impression Suqian, A millennium ancient city in China, Great Xichu Conqueror Xiangyu's hometown, Birthplace of Chuhan culture, Layers of ancient cities buried. Yellow River (the National Mother River 5,464km) and Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal (the National Wisdom River 1794km, declaring the World Cultural Heritage) run through it. With Luoma, Hongze Lake, it has "Two Rivers Two Lakes" unique spatial characteristics. Nowadays Suqian is meeting the challenge of leapfrog development and ‘Livable Cities’ transformation.The city area is 8555 square kilometers and the resident population is 4,725,100. In 2009 its GDP was RMB 82.685 billion, per capita GDP was RMB 1.75 million. It’s industrial structure is19.3:46.3:34.4, level of urbanization is 37.7% 1.2 Superiority Evaluation (1) industrial structure optimized continuously, overall strength increased significantly. (2) people's lives condition Improved. Urban residents per capita disposable income was 12000, increased 11.6% per year; Farmer’s per capita net income was 6,000, increased 8.9% per year. (3) City’s carrying capacity has improved significantly. infrastructure had remarkable results; the process of industrialization and urbanization process accelerated. (4) Good ecological environment. Good days for 331 days, good rate is 90.4%. (5) Profound historical accumulation. the ancient city, the birthplace of Chu and Han culture, the history of mankind living fossil 1.3 Development Opportunities (1) Expansion of the Yangtze River Delta. -

The Effect of Beijing-Shanghai High-Speed Railway on the Economic Development of Prefecture-Level Cities Along the Line Based on DID Model

E3S Web of Conferences 235, 01016 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202123501016 NETID 2020 The Effect of Beijing-Shanghai High-Speed Railway on the Economic Development of Prefecture-Level Cities Along the Line Based on DID Model Ma Yuzhou1 1School of Economics and Management, Beijing Jiaotong University, Beijing, China Abstract. High-speed railway has an essential impact on the economic and social development of the regions along the line. Based on the Beijing-Shanghai high-speed railway, this paper constructs the DID model and analyzes the impact of Beijing-Shanghai high-speed railway on the economic development of prefecture-level cities along the route from the empirical perspective. The empirical analysis results show that the Beijing- Shanghai high-speed railway has a significant negative impact on the per capita GDP of prefecture-level cities along the line in the short term, mainly because the agglomeration effect is greater than the diffusion effect. Therefore, small cities should actively think about how to deal with the agglomeration effect caused by the construction of high-speed rail. billion yuan. The line is a project with the most massive 1 Introduction scale and highest technique since the founding of China. The BSHSR, which owns faster speed, fewer stops, and Since the opening of Beijing-Tianjin intercity high-speed more running trains, adds a vital passenger transport railway in 2008, China's high-speed railway (abbreviated channel for the eastern region. BSHSR improves the to “HSR”, for short) has stepped into a rapid expansion transportation capacity of Beijing-Shanghai line, meets stage, and the "four vertical and four horizontal" HSR the ever-growing travel demand of passengers, and network planned and constructed by the state has taken strengthens the connection between the two urban clusters shape. -

Chapter 2 Beijing's Internal and External Challenges

CHAPTER 2 BEIJING’S INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL CHALLENGES Key Findings • The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is facing internal and external challenges as it attempts to maintain power at home and increase its influence abroad. China’s leadership is acutely aware of these challenges and is making a concerted effort to overcome them. • The CCP perceives Western values and democracy as weaken- ing the ideological commitment to China’s socialist system of Party cadres and the broader populace, which the Party views as a fundamental threat to its rule. General Secretary Xi Jin- ping has attempted to restore the CCP’s belief in its founding values to further consolidate control over nearly all of China’s government, economy, and society. His personal ascendancy within the CCP is in contrast to the previous consensus-based model established by his predecessors. Meanwhile, his signature anticorruption campaign has contributed to bureaucratic confu- sion and paralysis while failing to resolve the endemic corrup- tion plaguing China’s governing system. • China’s current economic challenges include slowing econom- ic growth, a struggling private sector, rising debt levels, and a rapidly-aging population. Beijing’s deleveraging campaign has been a major drag on growth and disproportionately affects the private sector. Rather than attempt to energize China’s econo- my through market reforms, the policy emphasis under General Secretary Xi has shifted markedly toward state control. • Beijing views its dependence on foreign intellectual property as undermining its ambition to become a global power and a threat to its technological independence. China has accelerated its efforts to develop advanced technologies to move up the eco- nomic value chain and reduce its dependence on foreign tech- nology, which it views as both a critical economic and security vulnerability. -

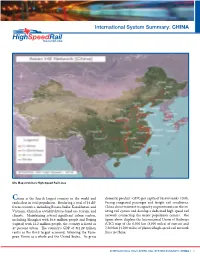

International System Summary: CHINA

International System Summary: CHINA UIC Map of China’s High-Speed Rail Lines China is the fourth largest country in the world and domestic product (GDP) per capita of $8,400 ranks 120th. ranks first in total population. Bordering a total of 14 dif- Facing congested passenger and freight rail conditions, ferent countries, including Russia, India, Kazakhstan, and China chose to invest in capacity improvements on the ex- Vietnam, China has a widely diverse land use, terrain, and isting rail system and develop a dedicated high-speed rail climate. Maintaining several significant urban centers, network connecting the major population centers. The including Shanghai with 16.6 million people and Beijing figure above displays the International Union of Railways (capital) with 12.2 million people, the country is listed as (UIC) map of the 6,300 km (3,900 miles) of current and 47 percent urban. The country’s GDP of $11.29 trillion 7,200 km (4,500 miles) of planned high-speed rail network ranks as the third largest economy, following the Euro- lines in China. pean Union as a whole and the United States.. Its gross INTERNATIONAL HIGH-SPEED RAIL SYSTEM SUMMARY: CHINA | 1 SY STEM DESCRIPTION AND HISTORY Speed Year Length Stage According to the UIC, the first high-speed rail line seg- km/h mph Opened km miles ment in the China opened in 2003 between Qinhuangdao Under Consturction: Guangzhou – Zhuhai 160 100 2011 49 30 and Shenyang. The 405 km (252 mile) segment operates (include Extend Line) at a speed of 200 km/h (125 mph) is now part of a 6,299 Wuhan – Yichang 300 185 2011 293 182 km (3,914 mile) network of high-speed rail lines stretching Tianjin – Qinhuangdao 300 185 2011 261 162 across China operating at maximum operating speeds of Nanjing – Hangzhou 300 185 2011 249 155 at least 160 km/h (100 mph) as shown in the table below. -

Current Trends of the Prevalence of Childhood Asthma in Three Chinese Cities : a Multicenter Epidemiological Survey1

BIOMEDICAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES 23, 453-457 (2010) www.besjournal.com www.besjournal.com Current Trends of the Prevalence of Childhood Asthma in Three Chinese Cities : A Multicenter Epidemiological Survey1 * *,2 # # & & JUAN BAI , JING ZHAO , KUN-LING SHEN , LI XIANG , AI-HUAN CHEN , SUI HUANG , § $ @ YING HUANG , JIAN-SHENG WANG , AND RONG-WEI YE *Capital Institute of Pediatrics, Beijing 100020, China; #Beijing Children’s Hospital attached to Capital Medical University, Beijing 100045, China; &GuangZhou Institute of Respiratory Diseases, Guangzhou 510120, Guangdong, China; §Children’s Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing 400014, China; $Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, Beijing 100050, China Objective To analyze the prevalence of asthma and asthma related symptoms among children aged 0-14 years in three Chinese cities and to obtain a crude estimation of the trend of childhood asthma prevalence in China. Methods A cross-sectional, population-based survey of prevalence of asthma was conducted in children aged from 0 to 14 years in 3 major cities of China (Beijing, Chongqing, and Guangzhou) with different geographic locations. All the subjects were randomly selected by a multi-stage sampling method. Three to five schools and kindergartens in 2 urban districts in each city were randomly selected for the survey, and a validated questionnaire that included the core questions of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood, Phase III questionnaire and several additional questions were used. All questionnaires were completed by parents or guardians of the selected children. Children whose parents responded affirmatively to the question” Has your child ever been diagnosed as asthma by a doctor” were recognized as victims of asthma. -

BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT MISSION TRIP to BEIJING, SHANGHAI, & TIANJIN, CHINA May 5 - 16, 2016

ARTS & CULTURE AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT FOR 7TH AVENUE CHINATOWN PLANS NORTH MIAMI, FL BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT MISSION TRIP TO BEIJING, SHANGHAI, & TIANJIN, CHINA May 5 - 16, 2016 ROUNDTRIP AIRFARE VISA ENTRY REQUIREMENTS Participants are responsible urged to arrive in no U.S. citizens must have a valid passport. U.S. citizens require later than , 2016. an entry visa for The People’s Republic of China. and Beijing PROPOSED MISSION ITINERARY Consulate General of May 6 The People’s Republic of China in Houston Beijing, China 4317 Montrose Blvd, Houston, TX 77006 May 5: Depart for . Tel: (713) 520-462; Fax: (713) 521-3064 May 6: Arrive in . Website: http://houston.china-consulate.org. May 7 - 8: Official meetings,Beijing, China networking & B2B match- Visa Office Hours (Mon -Fri) making meetings, Beibriefingsjing & branding presentations, etc. 9:00AM - 11:30AM & 1:30PM - 3:00PM CURRENCY The Chinese currency is Chinese yuan, also known as with the Chamber of Commerce and Business Association on Renminbi (RMB) is used throughout mainland China. The Mayopportunities 9: for investment in North Miami's 7th avenue, ¥) MayCRA incentives.10: , Tours of the Forbidden City. Shanghai, China basic unit of RMB is Yuan ( . In some parts of China, yuan May 10: Depart Beijing for /OfficialShanghai meetings (PM). isWEATHER called kuai. 10 CNY = $0.15US(approx).) May 10: Visit Average high/low temperatures ( . Arrive in Shanghai . Beijing: oF / oF Shanghai Economic and Technological May 11: Shanghai: 7 oF / oF May) Development Zones Tianjin: 77979oF / 57oF May 12: Official meetings, networking & B2B match-making 5 61 Maymeetings, 13: briefings and branding presentations, etc. -

People's Republic of China: Preparing the Jilin Urban Infrastructure Project

Technical Assistance Report Project Number: 40050 June 2006 People’s Republic of China: Preparing the Jilin Urban Infrastructure Project CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 30 May 2006) Currency Unit – yuan (CNY) CNY1.00 = $0.124 $1.00 = CNY8.08 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank CMG – Changchun municipal government EIA – environmental impact assessment EMP – environmental management plan FSR – feasibility study report IA – implementing agency JPG – Jilin provincial government JUIP – Jilin Urban Infrastructure Project JWSSD – Jilin Water Supply and Sewerage Development m3 – cubic meter mg – milligram PMO – project management office PRC – People’s Republic of China RP – resettlement plan SEIA – summary environmental impact assessment SRB – Songhua River Basin TA – technical assistance YMG – Yanji municipal government TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE CLASSIFICATION Targeting Classification – Targeted intervention Sectors – Water supply, sanitation, and waste management Subsector – Water supply and sanitation Themes – Sustainable economic growth, inclusive social development, environmental sustainability Subthemes – Human development, urban environmental improvement NOTE In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. Vice President C. Lawrence Greenwood, Jr., Operations Group 2 Director General H. Satish Rao, East Asia Department (EARD) Director R. Wihtol, Social Sectors Division, EARD Team leader S. Penjor, Principal Financial Specialist, EARD Map 1 118 o 00'E 130o 00'E JILIN URBAN INFRASTRUCTURE PROJECT IN THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA N 0 100 200 300 400 Kilometers Songhua River Basin (water pollution affected areas) National Capital Provincial Capital City/Town H e i l River o n g Watershed Boundary o R o 52 00'N i 52 00'N v e Provincial Boundary X r Yilehuli Mountain I A International Boundary O S Boundaries are not necessarily authoritative. -

Costs and Benefits of a Pearl River Delta Emission Control Area

COSTS AND BENEFITS OF A PEARL RIVER DELTA EMISSION CONTROL AREA XIAOLI MAO, CHEN CHEN, BRYAN COMER, PH.D., DAN RUTHERFORD, PH.D. JULY 2019 www.theicct.org [email protected] BEIJING | BERLIN | BRUSSELS | SAN FRANCISCO | WASHINGTON ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors thank members of the International Association for Catalytic Control of Ship Emissions to Air and Dr. Chuansheng Peng for the critical reviews and thoughtful recommendations, and our colleagues Josh Miller, Jennifer Callahan, and Hongyang Cui for their tremendous support in review and proofreading. We especially thank the Health Effects Institute for its generous support in providing mortality data. We also acknowledge Tsinghua University for providing gridded emissions inventory data for land-based sources in China for 2015 and 2030. This study was funded by Energy Foundation China with support from Bloomberg Philanthropies. International Council on Clean Transportation 1500 K Street NW Suite 650 Washington DC 20005 USA [email protected] | www.theicct.org | @TheICCT © 2019 International Council on Clean Transportation COSTS AND BENEFITS OF A PEARL RIVER DELTA EMISSION CONTROL AREA EXECUTIVE SUMMARY An Emission Control Area (ECA) is a special area designated by the International Maritime Organization (IMO)—the specialized United Nations agency responsible for regulating international shipping—where a country or group of countries can enforce more stringent air emission standards to improve air quality and protect the environment. There are currently four ECAs in the world, each protecting densely populated coastal regions that experience heavy ship traffic. Although China has one of the most densely populated coastal areas on Earth and is home to some of the world’s busiest ports, it is not protected by an ECA.