Transforming the Transformed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Navy Columbia-Class Ballistic Missile Submarine Program

Navy Columbia (SSBN-826) Class Ballistic Missile Submarine Program: Background and Issues for Congress Updated September 14, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R41129 Navy Columbia (SSBN-826) Class Ballistic Missile Submarine Program Summary The Navy’s Columbia (SSBN-826) class ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) program is a program to design and build a class of 12 new SSBNs to replace the Navy’s current force of 14 aging Ohio-class SSBNs. Since 2013, the Navy has consistently identified the Columbia-class program as the Navy’s top priority program. The Navy procured the first Columbia-class boat in FY2021 and wants to procure the second boat in the class in FY2024. The Navy’s proposed FY2022 budget requests $3,003.0 (i.e., $3.0 billion) in procurement funding for the first Columbia-class boat and $1,644.0 million (i.e., about $1.6 billion) in advance procurement (AP) funding for the second boat, for a combined FY2022 procurement and AP funding request of $4,647.0 million (i.e., about $4.6 billion). The Navy’s FY2022 budget submission estimates the procurement cost of the first Columbia- class boat at $15,030.5 million (i.e., about $15.0 billion) in then-year dollars, including $6,557.6 million (i.e., about $6.60 billion) in costs for plans, meaning (essentially) the detail design/nonrecurring engineering (DD/NRE) costs for the Columbia class. (It is a long-standing Navy budgetary practice to incorporate the DD/NRE costs for a new class of ship into the total procurement cost of the first ship in the class.) Excluding costs for plans, the estimated hands-on construction cost of the first ship is $8,473.0 million (i.e., about $8.5 billion). -

E10 Trondheim Norway

E10TRONDHEIM_NORWAY EUROPAN 10 TRONDHEIM_NORWAY 2 DEAR EUROPAN CONTENDERS xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx -

Kulturminneplan Nyhavna

Kulturminneplan Nyhavna - Kulturhistorisk stedsanalyse av Dora ubåtanlegg Forord Kulturmiljøet på Nyhavna består av 13 bygninger: 2 ubåtbunkere, en fyringsbunker, 2 spissbunkere og et antall øvrige verksted- og verftsbygninger. Bygningene er gitt verneklasse A, B eller C på Trondheim kommunes aktsomhetskart og har stor krigshistorisk verdi. Anlegget har nasjonal og internasjonal betydning og står som et av flere bindeledd i felles Europeisk krigskulturarv. Nyhavna, Reina og nærliggende områder skal utvikles som ny urban bydel. Med det utløses et behov for kartlegging og plan for bevaring av de kulturhistoriske elementene i landskapet. Kulturminneplanen for Nyhavna skal tjene som et verktøy i plan- og utviklingsarbeidet og inngår i kommuneplanens arealdel. Planen skal sørge for at utvikling skjer i samspill med bevaring av kulturverdiene i området. Med utgangspunkt i detaljert analyse og samlet verdigrunnlag blir tålegrenser, handlingsrom og utviklingspotensial vurdert for hvert enkelt bygg og kulturmiljøet som helhet. Denne analysen er utført etter DIVE-metoden; et verktøy utviklet av blant annet Riksantikvaren i et nordisk samarbeid. Grunnlagsmaterialet er utarbeidet av Byantikvaren i Trondheim kommune. Takk til Obos, Trondheim Havn, Dora AS, Forsvarsmuseet Rustkammerets magasin og Marinemuseet i Horten for godt samarbeid. Stine Haga Runden Byantikvaren i Trondheim 2019 Innholdsfortegnelse 1. Innledning 1.1 Bakgrunn 1.2 DIVE-metoden 1.3 Definisjoner 1.4 Verdigrunnlag 1.5 Tilstandsvurdering 1.6 Kommunedelplan for kulturminner og kulturmiljøer -

(Iowa City, Iowa), 1943-03-07

...... ... ... _,- ... .. .. Ration Calendar Continued Cold OAI "1\" ••• p.n 4 UII.". lII .... b .11 ,Vt:L on. •••pvn _ explr .. Ap.1I U, IOWA: C.. ttlDlIfd eo" today, low. 00"1'11" '.UPOtl 28 expl .., 111 ..." II I est temperature lero to 8 sua". .oupon Ij • pi rei III•• " 161 TilE DAILY IOWAN 8HO.I, .oup... n upl... J.D. U. Iowa City/s Morning Newspaper below ID lOath portloa. fIVE CENTS TBI AS80ClATBD PBE88 IOWA CITY, IOWA SUNDAY, MARCH 1, 1943 THB ASSOCIATBD na VOLUME XLID NUMBER 138 • GERMAN SAILORS F!EL WRATH OF BRITISH JACKTARS .Rommel Begi.ns D~ive Against British 'Eighth' Russians Take lone American Sub Sinks 13 Jap Ships; Lashes Oul Along Mareth line Gzhatsk, Nazi Commander Describes BaHle Experiences In Savage 'Delaying' Assault hat WASHINGTON (AP) - The Chappel explalned. "After a very de navy disclosed last night that a few minutes that ship blew up with ALLIED HEADQUARTER IN ·ORTH AFRICA (AP) single American submarine has the damnedest explosion I ever Defense Point saw. I guess he was loaded with t\[arsbal En\'in Rommel' axi fore la ht'd outll\'agt'ly at the sunk 13 Japancse srupS-IO cargo ammunition," British Eil!'hth army at da\D1 y terda), in Ull ofrt'll i"\'l~ aguin t vessels and three warships, A few month alter Pearl Har en. ir Beruard Montgomery for the fil t time ' in~c the battle City's Seizure Blunts The submarine, which was not bor, Chappell and his crew had of El Alameiu in Egypt. named, was commanded by Li ut. -

Type XXI Submarine 1 Type XXI Submarine

Type XXI submarine 1 Type XXI submarine U-3008 in U.S. Navy service in 1948. Class overview Name: Type XXI U-boat Operators: Kriegsmarine Postwar: French Navy German Navy Royal Navy Soviet Navy United States Navy [1] Cost: 5.750.000 Reichsmark per boat Built: 1943–45 [2] Building: 267 Planned: 1170 Completed: 118 Cancelled: 785 General characteristics Class & type: Submarine Displacement: 1,621 t (1,595 long tons) surfaced 1,819 t (1,790 long tons) submerged Length: 76.7 m (251 ft 8 in) Beam: 8 m (26 ft 3 in) Draught: 6.32 m (20 ft 9 in) Propulsion: Diesel/Electric 2× MAN M6V40/46KBB supercharged 6-cylinder diesel engines, 4,000 shp (3,000 kW) 2× SSW GU365/30 double acting electric motors, 5,000 PS (3.7 MW) 2 × SSW GV232/28 silent running electric motors, 226 shp (169 kW) Speed: 15.6 kn (28.9 km/h) surfaced 17.2 kn (31.9 km/h) submerged 6.1 kn (11.3 km/h) (silent running motors) Type XXI submarine 2 Range: 15,500 nmi (28,700 km) at 10 kn (19 km/h) surfaced 340 nmi (630 km) at 5 kn (9.3 km/h) submerged Test depth: 240 m (787 ft) [3] Complement: 5 officers, 52 enlisted men Armament: 6 × 53.3 cm (21.0 in) torpedo tubes (bow), 23 torpedoes (or 17 torpedoes and 12 mines) 4 x 2 cm (0.8 in) anti-aircraft guns Type XXI U-boats, also known as "Elektroboote" (German: "electric boats"), were the first submarines designed to operate primarily submerged, rather than as surface ships that could submerge as a means to escape detection or launch an attack. -

Osprey Publishing, Elms Court, Chapel Way, Botley, Oxford OX2 9LP, United Kingdom

WOLF PACK The Story of the U-Boat in World War II The Story - oat iq-Workd War 11 First published in Great Britain in 2005 by Osprey Publishing, Elms Court, Chapel Way, Botley, Oxford OX2 9LP, United Kingdom. Email: [email protected] Previously published as New Vanguard 51: Kriegsmarine U-boats 1939-45 (1); New Vanguard 55: Kriegsmarine U-boats 1939-45 (2); and Warrior 36: Grey Wolf. © 2005 Osprey Publishing Ltd. All rights reserved. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrical, chemical, mechanical, optical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. Enquiries should be addressed to the Publishers. CIP data for this publication is available from the British Library. ISBN 1 84176 872 3 Editors: Anita Hitchings and Ruth Sheppard Design: Ken Vail Graphic Design, Cambridge, UK Artwork by Ian Palmer and Darko Pavlovic Index by Alan Thatcher Originated by The Electronic Page Company, Cwmbran, UK Printed and bound by L-Rex Printing Company Ltd 05 06 07 08 09 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 FOR A CATALOGUE OF ALL BOOKS PUBLISHED BY OSPREY PLEASE CONTACT: NORTH AMERICA Osprey Direct, 2427 Bond Street, University Park, IL 60466, USA E-mail: [email protected] ALL OTHER REGIONS Osprey Direct UK, P.O. Box 140, Wellingborough, Northants, NN8 2FA, UK E-mail: [email protected] www.ospreypublishing.com EDITOR'S NOTE All photographs, unless indicated otherwise, are courtesy of the U-Boot Archiv. -

The Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial – a Guide to The

PUBLISHED BY Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial Jean-Dolidier-Weg 75 21039 Hamburg Phone: +49 40 428131-500 [email protected] www.kz-gedenkstaette-neuengamme.de EDITED BY Karin Schawe TRANSLATED BY Georg Felix Harsch PHOTOS unless otherwise indicated courtesy We would like to thank the Friends of of the Neuengamme Memorial‘s Archive the Neuengamme Memorial association and Michael Kottmeier for their financial support. Maps on pages 29 and 41: © by M. Teßmer, graphische werkstätten This brochure was produced with feldstraße financial support from the Federal Commissioner for Culture and the Media GRAPHIC DESIGN BY based on a decision by the Bundestag, Annrika Kiefer, Hamburg the German parliament. The Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial – PRINTED BY A Guide to the Site‘s History and the Memorial Druckerei Siepmann GmbH, Hamburg Hamburg, November 2010 The Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial – A Guide to the Site‘s History and the Memorial The Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial – A Guide to the Site's History and the Memorial Published by the Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial Edited by Karin Schawe Contents 6 Preface 10 The NeueNgamme coNceNTraTioN camP, 1938 To 1945 12 chronicle of events, 1938 to 1945 20 The construction of the Neuengamme concentration camp 22 The Prisoners 22 German Prisoners 25 Prisoners from the Occupied Countries 30 The concentration camp SS 31 Slave Labour 35 housing 38 Death 40 The Satellite camps 42 The end 45 The Victims of the Neuengamme concentration camp 46 The SiTe afTer 1945 48 chronicle of events from 1945 58 The British internment camp 59 The Transit camp 60 The Prisons and the memorial at the historical Site of the concentration camp Contents 66 The NeueNgamme coNceNTraTioN camP memoriaL 70 The grounds 93 archives and Library 70 The house of commemoration 93 The Archive 72 The exhibitions 95 The Library 72 Main Exhibition Traces of History 96 The Open Archive 73 Research Exhibition Posted to Neuengamme. -

Reconstruction on Display: Arkitektenes Høstutstilling 1947–1949 As Site for Disciplinary Formation

Reconstruction on Display: Arkitektenes høstutstilling 1947–1949 as Site for Disciplinary Formation by Ingrid Dobloug Roede Master of Architecture The Oslo School of Architecture and Design, 2016 Submitted to the Department of Architecture in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology June 2019 © 2019 Ingrid Dobloug Roede. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: Department of Architecture May 23, 2019 Certified by: Mark Jarzombek Professor of the History and Theory of Architecture Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: Nasser Rabbat Aga Khan Professor Chair of Department Committee for Graduate Students Committee Mark Jarzombek, PhD Professor of the History and Theory of Architecture Advisor Timothy Hyde, MArch, PhD Associate Professor of the History of Architecture Reader 2 Reconstruction on Display: Arkitektenes høstutstilling 1947-1949 As Site for Disciplinary Formation by Ingrid Dobloug Roede Submitted to the Department of Architecture on May 23, 2019 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies Abstract With the liberation of Norway in 1945—after a war that left large parts of the country in ruins, had displaced tenfold thousands of people, and put a halt to civilian building projects—Norwegian architects faced an unparalleled demand for their services. As societal stabilization commenced, members of the Norwegian Association of Architects (NAL) were consumed by the following question: what would—and should—be the architect’s role in postwar society? To publicly articulate a satisfying answer, NAL organized a series of architectural exhibitions in the years 1947–1949. -

By Film) Ursula Biemann

video screenings and exhibitions (by film) Ursula Biemann Acoustic Ocean 2018 Geomorphic Videos, Anthology Film Archives, New York, US Eco Visionaries, Haus der elektronischen Künste, Basel, CH Zeitspuren - The Power of Now, Centre Pasquart, Biel/Bienne, CH Propositions, Helmhaus, Zürich, CH After the Future - in the wake of utopian imaginar, National Marine Acquarium, Plymouth, UK Eco Visionaries, Bildmuseet, Umea, Sweden Between Bodies, Henry Art Gallery, University of Washington, Seattle, US Post-Nature: An Exhibition as an Ecosystem, Taipei Biennial, Taipei, Taiwan 2019 Eco Visionaries, LABoral Centro de Arte, Gijon, ES After Nature. Post-naturaleza y creación contempor, Circulo Bellas Artes, Madrid, ES Ozeanische Gefühle, Hessisches Landesmuseum , Darmstadt, DE The Edge of the Sea, Art Museum KUBE, Ålesund, NO Acoustic Ocean, The CUBE - TLH théâtre les Halles, Sierre, CH Art in the Anthropocene, Trinity College , Dublin, IR Logics of Sense 1: Investigations, Blackwood Gallery, Toronto, CA Öko-logics. Die neuen Sphären der Welt, E-WERK , Freiburg i.B., DE The Logic of Vertigo, Biennale of Media Art, Santiago, CL Vibrant Matter, Casa Encendida, Madrid, Spain Eco Visionaries, Royal Academy of Arts, London, UK Vibrant Matter, Más Arte Más Acción, Bogota, CO 2020 End to End - Transmediale, HKW, Berlin, DE Acoustic Ocean, Centre Culturel Suisse, Paris, FR Screening Ursula Biemann, Kunstmuseum Basel Gegenwart, Basel, CH FRAMING art film festival, Airport Art Center , Tel Aviv, IL Inhale, OFF-Biennale Budapest, Budapest, HU Destination Collection, -

September 2007 Tom Wallgren 612-789-7231 Outside Metro Call 1-888-840-8821 [email protected] 16 Year Member of the Nord Stern Region of PCA

Nord Stern September 2007 Tom Wallgren 612-789-7231 Outside Metro call 1-888-840-8821 [email protected] 16 year member of the Nord Stern Region of PCA In busiiness siince 1945 Specializing in - We represent a carefully selected group of Home Commercial financially sound, reputable insurance companies; Auto Life therefore, we are able to offer you excellent Collector vehicles Long term care coverage at a very competitive price. We do not work for an insurance company We work for you Nord Stern SEpteber 2007 Dedicated to the belief that . getting there is half the fun. Table of Contents 11 Nord Stern Annual BIR Club Race . 12 Carmudgeon Chronicles . Departments 14 Porsche Announces . 4 2007 Officers & Committee Chairs 19 World Touring - I Saw What? 5 From the Editor. 22 Porsche Reveals Early Stages of New Cayenne Hybrid 5 Biz Talk . 23 2007 San Diego Parade 6 Welcome 24 Porsche Announces Price and Launch Date for New 7 The Prez Sez . Limited Edition Boxster 8 Letters to the Editor . 34 What a RIDE Moscow to Mongolia 9 Car Biz Board . Upcoming Events 19 Guess the Member! 18 2007 Kalender . 26 Ted’s Technology, Trivia and Tidbits . 24 Cayman Corner: Croctoberfest 30 Tech Quiz . 25 PCA ZONE 10 CALENDAR UPDATE 31 For Sale . 27 Rennsport Reunion III . November 2-4, 2007 Update Features 29 2007 PCA Escape October 11-14th 10 Hey, Time for Some Fun at Last Fling! 11 Nord Stern Charitable Efforts ‘Pay off!’ Nord Stern is the official monthly publication of the Nord Stern NORD STERN STAFF Region, PCA Inc. -

Cruise Excursions

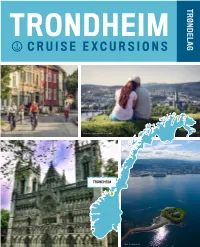

TRØNDELAG TRONDHEIM CRUISE EXCURSIONS Photo: Steen Søderholm / trondelag.com Photo: Steen Søderholm / trondelag.com TRONDHEIM Photo: Marnie VIkan Firing Photo: Trondheim Havn TRONDHEIM TRØNDELAG THE ROYAL CAPITAL OF NORWAY THE HEART OF NORWEGIAN HISTORY Trondheim was founded by Viking King Olav Tryggvason in AD 997. A journey in Trøndelag, also known as Central-Norway, will give It was the nation’s first capital, and continues to be the historical you plenty of unforgettable stories to tell when you get back home. capital of Norway. The city is surrounded by lovely forested hills, Trøndelag is like Norway in miniature. Within few hours from Trond- and the Nidelven River winds through the city. The charming old heim, the historical capital of Norway, you can reach the coastline streets at Bakklandet bring you back to architectural traditions and with beautiful archipelagos and its coastal culture, the historical the atmosphere of days gone by. It has been, and still is, a popular cultural landscape around the Trondheim Fjord and the mountains pilgrimage site, due to the famous Nidaros Cathedral. Trondheim in the national parks where the snow never melts. Observe exotic is the 3rd largest city in Norway – vivid and lively, with everything animals like musk ox or moose in their natural environment, join a a big city can offer, but still with the friendliness of small towns. fishing trip in one of the best angler regions in the world or follow While medieval times still have their mark on the center, innovation the tracks of the Vikings. If you want to combine impressive nature and modernity shape it. -

3D Recording, Modelling And

The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XL-5/W4, 2015 3D Virtual Reconstruction and Visualization of Complex Architectures, 25-27 February 2015, Avila, Spain 3D RECORDING, MODELLING AND VISUALISATION OF THE FORTIFICATION KRISTIANSTEN IN TRONDHEIM (NORWAY) BY PHOTOGRAMMETRIC METHODS AND TERRESTRIAL LASER SCANNING IN THE FRAMEWORK OF ERASMUS PROGRAMMES T. Kersten a, *, M. Lindstaedt a, L. Maziull a, K. Schreyer a, F. Tschirschwitz a and K. Holm b a HafenCity University Hamburg, Photogrammetry & Laserscanning Lab, Überseeallee 16, 20457 Hamburg -(thomas.kersten, maren.lindstaedt, kristin.schreyer, felix.tschirschwitz)@hcu-hamburg.de, [email protected] b NTNU - Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Division of Roads, Transport, and Geomatics, Høgskoleringen 7 A, NO-7491 Trondheim, Norway - [email protected] Commission V – WG V/4 KEY WORDS: 3D, CAD, meshing, model, reconstruction, virtual ABSTRACT: In this contribution the 3D recording, 3D modelling and 3D visualisation of the fortification Kristiansten in Trondheim (Norway) by digital photogrammetry and terrestrial laser scanning are presented. The fortification Kristiansten was built after the large city fire in the year 1681 above the city and has been a museum since 1997. The recording of the fortress took place in each case at the end of August/at the beginning of September 2010 and 2011 during two two-week summer schools with the topic “Digital Photogrammetry & Terrestrial Laser Scanning for Cultural Heritage Documentation” at NTNU Trondheim with international students in the context of ERASMUS teaching programs. For data acquisition, a terrestrial laser scanner and digital SLR cameras were used. The establishment of a geodetic 3D network, which was later transformed into the Norwegian UTM coordinate system using control points, ensured a consistent registration of the scans and an orientation of the photogrammetric images.