Alaris Capture Pro Software

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elizabeth Woodville and Margery Kempe, Female Agency in Late Medieval England

ABSTRACT “She Should Have More if She Were Ruled and Guided by Them”: Elizabeth Woodville and Margery Kempe, Female Agency in Late Medieval England Laura Christine Oliver, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Beth Allison Barr, Ph.D. This thesis argues that while patriarchy was certainly present in England during the late medieval period, women of the middle and upper classes were able to exercise agency to a certain degree through using both the patriarchal bargain and an economy of makeshifts. While the methods used by women differed due to the resources available to them, the agency afforded women by the patriarchal bargain and economy of makeshifts was not limited to the aristocracy. Using Elizabeth Woodville and Margery Kempe as cases studies, this thesis examines how these women exercised at least a limited form of agency. Additionally, this thesis examines whether ordinary women have access to the same agency as elite women. Although both were exceptional women during this period, they still serve as ideal case studies because of the sources available about them and their status as role models among their contemporaries. “She Should Have More if She Were Ruled and Guided By Them”: Elizabeth Woodville and Margery Kempe, Female Agency in Late Medieval England by Laura Christine Oliver, B.A. A Thesis Approved by the Department of History ___________________________________ Jeffrey S. Hamilton, Ph.D., Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee ___________________________________ Beth Allison Barr, Ph.D., Chairperson ___________________________________ Julie A. -

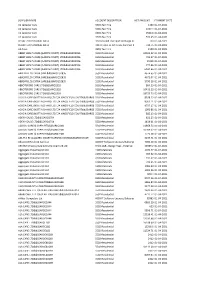

Payments to Suppliers Over £500 (ALL) April 2021

SUPPLIER NAME ACCOUNT DESCRIPTION NET AMOUNT PAYMENT DATE A1 Leicester Cars 3303-Taxi Hire 1160 01-04-2021 A1 Leicester Cars 3303-Taxi Hire 1037.4 01-04-2021 A1 Leicester Cars 3303-Taxi Hire 1504.8 01-04-2021 A1 Leicester Cars 3303-Taxi Hire 599.25 01-04-2021 REDACTED PERSONAL DATA 3201-Pooled Transport Recharge Inhouse 720 01-04-2021 REDACTED PERSONAL DATA 3113-Home to Sch Trans Contract Buses Sec 746.75 01-04-2021 AA Taxis 3303-Taxi Hire 1500 01-04-2021 ABBEY HEALTHCARE (AARON COURT) LTD&&SSARO2996 5502-Residential 34592.32 01-04-2021 ABBEY HEALTHCARE (AARON COURT) LTD&&SSARO2996 5502-Residential 703.57 01-04-2021 ABBEY HEALTHCARE (AARON COURT) LTD&&SSARO2996 5502-Residential 19218 01-04-2021 ABBEY HEALTHCARE (AARON COURT) LTD&&SSARO2996 5502-Residential 777.86 01-04-2021 ABBEY HEALTHCARE (AARON COURT) LTD&&SSARO2996 5502-Residential 6547.86 01-04-2021 ABBEYFIELDS EXTRA CARE&&SSAROE52835 5502-Residential 4674.65 01-04-2021 ABBEYFIELDS EXTRA CARE&&SSAROE52835 5502-Residential 4672.07 01-04-2021 ABBEYFIELDS EXTRA CARE&&SSAROE52835 5502-Residential 3790.28 01-04-2021 ABBOTSFORD CARE LTD&&SSARO2339 5502-Residential 864.29 01-04-2021 ABBOTSFORD CARE LTD&&SSARO2339 5502-Residential 10403.23 01-04-2021 ABBOTSFORD CARE LTD&&SSARO2339 5502-Residential 18725.73 01-04-2021 ACACIA CARE (NOTTINGHAM) LTD T/A KINGSFIELD COURT&&SSARO85405502-Residential 8528.12 01-04-2021 ACACIA CARE (NOTTINGHAM) LTD T/A KINGSFIELD COURT&&SSARO85405502-Residential 9052.71 01-04-2021 ACACIA CARE (NOTTINGHAM) LTD T/A KINGSFIELD COURT&&SSARO85405502-Residential 9707.17 -

Jex-Blake, T W, Historical Notices of Robert Stillington; Chancellor of England, Bishop of Bath & Wells

; Proceedings of the Somersetshire A rchceological and Natural History Society, 1894, Part II. PAPE11S, ETC. historical jQotices of Etobert ©ttlUngton Chancellor of CnglanD, iBis&op of TBatf) $ aBelte. BY THE VERY REV. T. W. JEX-BLAKE, D.D. (Dean of Wells.) AKLY in 1894 the Dean and Chapter of Wells made * -* extensive excavations east of the Cloisters and south of the Cathedral, to ascertain the exact site, condition, and measurements of the foundations of two chapels, of the thir- teenth and fifteenth centuries respectively. The chapel of the fifteenth century was known to be Bishop Stillington's, and was found to be of unexpected magnificence ; a second cathedral, in fact, with transepts ; 120 feet long from east to west, and 66 feet from north to south in the transepts. The foundations were superb, as will be seen from the architectural plans and descriptions made in detail by Mr. Edmund Buckle, the Diocesan Architect. New Series, Vol. XX. II. a , 1894, Part 2 Papers, 8fc. Canon Church undertook to collect the notices of Bishop Stillington and his work, in the Diocesan Registers and the Cathedral Eecords : and at the request of Mr. Elworthy, our Secretary, I promised to find out and put together whatever I could learn of Bishop Stillington from ancient and modern history and records. His splendid chapel might have been standing to this day, as little injured as the Cathedral or the Chapter House by the troubles of the Cromwellian period, or by Monmouth's brief campaign, if only it had been spared for a twelvemonth : for it was destroyed in the very last year of Edward VI : the greed of a courtier trading on the need of the greatly impoverished Dean and Chapter. -

Ricardian Bulletin Dec 2019 Text Layout 1

ARTICLES ARDENT SUITOR OR RELUCTANT GROOM? Henry VII and Elizabeth of York Part 1: Ardent suitor DAVID JOHNSON On 18 January 1486 Henry VII married Elizabeth of York, symbolically uniting the royal houses of Lancaster and York and laying the foundations of Tudor dynastic success. By the time Henry’s court historian, Polydore Vergil, published his English History, the Anglica Historia, in 1534, the matrimonial union of these former adversaries had become a national panacea, evidence, no less, of God’s benediction: It is legitimate to attribute this [marriage] to divine intervention, for plainly by it all things which nourished the two most ruinous factions were utterly removed, by it the two houses of Lancaster and York were united and from the union the true and established royal line emerged which now reigns.1 Despite Vergil’s faith in the providential care of the Matrimonial conspiracy Almighty, Henry’s relationship with Elizabeth of York Henry’s union with Elizabeth of York was a consequence proved to be complex and unpredictable. If we strip of Richard III’s controversial accession in the summer of away the certainties of hindsight and track Henry’s 1483. In the autumn of that year, following the matrimonial destiny in real time, a remarkable story disappearance of the deposed Edward V and his younger begins to emerge. Instead of the divinely ordained brother, Richard, duke of York, a rebellion in the south dynastic alliance described by Vergil, we find a of England aimed to overthrow Richard and place the problematic, politically charged reality. This two‐part Lancastrian exile Henry Tudor on the throne. -

Northamptonshire Past and Present, No 61

JOURNAL OF THE NORTHAMPTONSHIRE RECORD SOCIETY WOOTTON HALL PARK, NORTHAMPTON NN4 8BQ ORTHAMPTONSHIRE CONTENTS Page NPAST AND PRESENT Notes and News . 5 Number 61 (2008) Fact and/or Folklore? The Case for St Pega of Peakirk Avril Lumley Prior . 7 The Peterborough Chronicles Nicholas Karn and Edmund King . 17 Fermour vs Stokes of Warmington: A Case Before Lady Margaret Beaufort’s Council, c. 1490-1500 Alan Rogers . 30 Daventry’s Craft Companies 1574-1675 Colin Davenport . 42 George London at Castle Ashby Peter McKay . 56 Rushton Hall and its Parklands: A Multi-Layered Landscape Jenny Burt . 64 Politics in Late Victorian and Edwardian Northamptonshire John Adams . 78 The Wakerley Calciner Furnaces Jack Rodney Laundon . 86 Joan Wake and the Northamptonshire Record Society Sir Hereward Wake . 88 The Northamptonshire Reference Database Barry and Liz Taylor . 94 Book Reviews . 95 Obituary Notices . 102 Index . 103 Cover illustration: Courteenhall House built in 1791 by Sir William Wake, 9th Baronet. Samuel Saxon, architect, and Humphry Repton, landscape designer. Number 61 2008 £3.50 NORTHAMPTONSHIRE PAST AND PRESENT PAST NORTHAMPTONSHIRE Northamptonshire Record Society NORTHAMPTONSHIRE PAST AND PRESENT 2008 Number 61 CONTENTS Page Notes and News . 5 Fact and/or Folklore? The Case for St Pega of Peakirk . 7 Avril Lumley Prior The Peterborough Chronicles . 17 Nicholas Karn and Edmund King Fermour vs Stokes of Warmington: A Case Before Lady Margaret Beaufort’s Council, c.1490-1500 . 30 Alan Rogers Daventry’s Craft Companies 1574-1675 . 42 Colin Davenport George London at Castle Ashby . 56 Peter McKay Rushton Hall and its Parklands: A Multi-Layered Landscape . -

Alaris Capture Pro Software

The Changing View from Oxford 1]]. Our Most Dread Sovereign .. R. C. HAIRSINE THE EXCITEMENT and speculations of those who rode into Oxford bearing news 'qf the battle near Leicester must have been quickly dampened by the sombre mood in the city and its university. The fate of princes and lords would hold little interest amidst fear of the new epidemic now raging within the walls. The ‘sweating sickness’ is thought by some to have been a particularly virulent strain of influenza,55 apparently previously unknown, which has since recurred at intervals till the present. The Register of Merton College provides a vivid record apparently written shortly after the disease subsidedzfi“ ‘The same year, about the end of August and the beginning of September, a strange' and unprecedented occurrence began in the university, which, coming with sudden sweating, has abruptly taken the lives of many. At length, about the end of September, the affliction spread just as suddenly . throughout the whole realm. In the City of London, three mayors died within ten days and thus, spreading from the east through the south and into _ the west,the extraordinary scourge smote almost all the nobles both spiritual 'and temporal short of the very high'est. Within twenty-four hours all either died or recovered. Such a sudden and cruel massacre, as it were, of the wise and good men among us has not been heard of for centuries. Apart from a few cases,the epidemic did not last beyond a month or six weeks. At length a remedy has been found against this extraordinary pestilence in that the infected person should be promptly covered by blankets for twenty-four hours, not to excess but in moderation (many in fact had been sufl‘ocated by cgvering with excess blankets), he should drink warm beer and not take any alr.’ Henry Tudor prudently delayed entry into London until the epidemic had subsided and his coronation was held (belatedly for those days) on 30th October. -

Featuring Articles on Henry Wyatt, Elizabeth of York, and Edward IV Inside Cover

Richard III Society, Inc. Vol. 42 No. 3 September, 2011 Challenge in the Mist by Graham Turner Dawn on the 14th April 1471, Richard Duke of Gloucester and his men strain to pick out the Lancastrian army through the thick mist that envelopes the battlefield at Barnet. Printed with permission l Copyright © 2000 Featuring articles on Henry Wyatt, Elizabeth of York, and Edward IV Inside cover (not printed) Contents The Questionable Legend of Henry Wyatt.............................................................2 Elizabeth of York: A Biographical Saga................................................................8 Edward IV King of England 1461-83, the original type two diabetic?................14 Duchess of York—Cecily Neville: 1415-1495....................................................19 Errata....................................................................................................................24 Scattered Standards..............................................................................................24 Reviews................................................................................................................25 Behind the Scenes.................................................................................................32 A Few Words from the Editor..............................................................................37 Sales Catalog–September, 2011...........................................................................38 Board, Staff, and Chapter Contacts......................................................................43 -

University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk i UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES School of History The Wydeviles 1066-1503 A Re-assessment by Lynda J. Pidgeon Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 15 December 2011 ii iii ABSTRACT Who were the Wydeviles? The family arrived with the Conqueror in 1066. As followers in the Conqueror’s army the Wydeviles rose through service with the Mowbray family. If we accept the definition given by Crouch and Turner for a brief period of time the Wydeviles qualified as barons in the twelfth century. This position was not maintained. By the thirteenth century the family had split into two distinct branches. The senior line settled in Yorkshire while the junior branch settled in Northamptonshire. The junior branch of the family gradually rose to prominence in the county through service as escheator, sheriff and knight of the shire. -

Richard III Society, Inc. Volume XXXX No. 3 Fall, 2009 REGISTER STAFF

Richard III Society, Inc. Volume XXXX No. 3 Fall, 2009 REGISTER STAFF EDITOR: Carole M. Rike 48299 Stafford Road • Tickfaw, LA 70466 ©2009 Richard III Society, Inc., American Branch. No part may be 985-350-6101 ° 504-952-4984 (cell) reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means — mechanical, email: [email protected] electrical or photocopying, recording or information storage retrieval — without written permission from the Society. Articles submitted by RICARDIAN READING EDITOR: Myrna Smith members remain the property of the author. The Ricardian Register is 2784 Avenue G • Ingleside, TX 78362 published four times per year. Subscriptions are available at $20.00 (361) 332-9363 • email: [email protected] annually. REGISTSER PROOFING: Susan Higginbotham In the belief that many features of the traditional accounts of the 405 Brierridge Drive • Apex, NC 27502 character and career of Richard III are neither supported by sufficient [email protected] evidence nor reasonably tenable, the Society aims to promote in every possible way research into the life and times of Richard III, and to secure a re-assessment of the material relating to the period, and of the role in English history of this monarch The Richard III Society is a nonprofit, educational corporation. In This Issue Dues, grants and contributions are tax-deductible to the extent allowed by law. Editorial License Dues are $50 annually for U.S. Addresses; $60 for international. Carole Rike. 3 Each additional family member is $5. Members of the American Society are also members of the English Society. Members also Gloucester’s Dukedom is too Ominous receive the English publications. -

The College and Canons of St Stephen's, Westminster, 1348

The College and Canons of St Stephen’s, Westminster, 1348 - 1548 Volume I of II Elizabeth Biggs PhD University of York History October 2016 Abstract This thesis is concerned with the college founded by Edward III in his principal palace of Westminster in 1348 and dissolved by Edward VI in 1548 in order to examine issues of royal patronage, the relationships of the Church to the Crown, and institutional networks across the later Middle Ages. As no internal archive survives from St Stephen’s College, this thesis depends on comparison with and reconstruction from royal records and the archives of other institutions, including those of its sister college, St George’s, Windsor. In so doing, it has two main aims: to place St Stephen’s College back into its place at the heart of Westminster’s political, religious and administrative life; and to develop a method for institutional history that is concerned more with connections than solely with the internal workings of a single institution. As there has been no full scholarly study of St Stephen’s College, this thesis provides a complete institutional history of the college from foundation to dissolution before turning to thematic consideration of its place in royal administration, music and worship, and the manor of Westminster. The circumstances and processes surrounding its foundation are compared with other such colleges to understand the multiple agencies that formed St Stephen’s, including that of the canons themselves. Kings and their relatives used St Stephen’s for their private worship and as a site of visible royal piety. -

Bishop of Bath and Wells 1466-91

The Register' of Robert Stillington, Bishop of Bath and Wells 1466-91 WILLIAM J. CONNOR This paper‘ seeks to show how the register dompiled for Robert Stillington, for twenty-five years bishop of Bath and Wells in the late fifteenth century, contributes to the understanding of the decoration of administrative documents in this period. It was largely compiled under the supervision of Hugh Sugar who, as vicar-general, was responsible for much of the routine administration of the diocese. He evidently encouraged the pen work embellishments, which are such a striking feature of this volume, and seems to have employed an artist whose only other known work appears in manuscripts commissioned by the previous bishop, Thomas Beckington. This links Stillington’s register directly to the academic elite of Winchester and New College, Oxford, and the culture of the Yorkist court. _ Dubbed re ”mumz': éué‘que by his French contemporary, Philippe de Commines,2 Robert Stillington enjoyed a colourful career. Probably born in Yorkshire c. 1410, he first appears in the records as a doctor of civil law at Oxford in 1443, by which time he was also a proctor of Lincoln College and principal of Deep Hall. At thispoint, probably already in his thirties, he embarked on the official and ecclesiastical career for which he is now remembered. A protégée of Thomas Beckington, the recently consecrated bishop of Bath and Wells, he was appointed as Beckington’s chancellor and to a prebend in Wells Cathedral in 1445, but not: ordained priest there until 1447. We then find him on a diplomatic mission to Burgundy in 1448 and as a royal councillor a year later. -

Philippe De Commynes and the Pre-Contract

ARTICLES PHILIPPE DE COMMYNES AND THE PRE-CONTRACT: what did Commynes say, where did he get his information, and what did he believe? DAVID JOHNSON Philippe de Commynes’ Memoirs of the Reign of Louis XI are unique among the primary sources for the reigns of Edward IV and Richard III as the only authority to state that Canon Robert Stillington, future bishop of Bath and Wells, participated in a secret marriage between Edward IV and ‘a certain English lady’ (Lady Eleanor Talbot). As we shall see, Commynes reported that Stillington ‘married them when only he and they were present’, that Edward subsequently wedded Queen Elizabeth Woodville, and that following Edward’s death, Stillington revealed the late king’s clandestine marriage to Richard, duke of Gloucester.1 Stillington’s testimony established Eleanor Talbot as It is interesting to note that Cato, as physician, served Edward’s legal wife and invalidated the king’s later and both Charles the Bold and Louis XI, just as Commynes, consequently bigamous union with Elizabeth Woodville. as diplomat, served the Burgundian duke and the French As a result, Edward’s legitimate contract of marriage to king.4 Towards the end of the Prologue Commynes Eleanor Talbot (the pre‐contract) disqualified the recasts the Memoirs in a more ambiguous light, stating offspring of the equally secret, but unlawful, Woodville that he sends to Cato ‘a record of that which springs union, leading to the deposition of Edward V and the promptly to my mind, hoping you asked for this in order accession of Richard III. Although Commynes is not to put it into a work which you have planned to write in alone in linking Stillington with the pre‐contract, his Latin’.5 Cato, however, ‘never wrote any such work, nor account is clearly of the utmost importance.