JMM Trunk Project 20Pgs 8-14-12

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

At CEEBJ from Rabbi the Sanctuary Was Filled to the Brim and It Jessica Wasn’T Even Rosh Hashanah Or Yom Kippur

HONORING TRADITIONS ENGAGING FAMILIES SUPPORTING COMMUNITIES Volume 92, No. 3 • September 2019 • Elul/Tishrei 5779/5780 A “Selig Experience” at CEEBJ From Rabbi The Sanctuary was filled to the brim and it Jessica wasn’t even Rosh Hashanah or Yom Kippur. Barolsky You ask – what was the occasion? It was Temple Brotherhood’s 10th Annual Public Family Sports The month leading Night which featured Allan H. (Bud) Selig as the up to Rosh Hashanah keynote speaker. The event’s objective was to col - is the month of Elul, lect non-perishable food and cash donations for which starts this year the Milwaukee Hunger Task Force and the Jewish on September 1. Community Pantry. The audience of over 200 Judaism gives us many Elul traditions to CEEBJers and their guests were extremely generous help make the upcoming Holy Days as their contributions exceeded expectations. more meaningful. Some blow the sho - far every day during Elul, in order to Mr. Selig spoke about a variety of sports-relat - wake up and inspire reflection. Some ed topics from his experiences as the add the words of Psalm 27 to daily (or Milwaukee Brewers’ Owner and as Major weekly) prayer, a psalm that focuses on League Baseball’s 9th Commissioner. The physical proximity with God and a audience thoroughly enjoyed the question deepening relationship to God. Here at and answer segment as Bud was very candid CEEBJ, we often sing one particular with his responses, often mixing in witty verse, which begins with the words replies to the delight of everyone. achat sha’alti, translated to “One thing I ask of the Eternal, only that do I seek: to Bud received a gorgeous University of Wisconsin live in the house of the Eternal all the (his alma mater) blanket from Dan Sinykin & Jodi days of my life, to gaze upon the beauty Habush. -

Jewish Wisconsin 5775-5776/2014-2015

A GUIDE TO Jewish Wisconsin 5775-5776/2014-2015 Your connection to Jewish Arts, Culture, Education, Camping and Religious Life Welcome from the Publisher Hannah Rosenthal Daniel Bader Welcome to A Guide to Jewish Wisconsin 5775-5776/ We also invite you to learn more about The Chronicle by 2014-2015, a publication of The Wisconsin Jewish visiting JewishChronicle.org. Visit MilwaukeeJewish.org Chronicle. The Guide is designed to help newcomers to learn more about the Milwaukee Jewish Federation, become acquainted with our state’s vibrant Jewish which publishes both the Guide and The Chronicle as community and to help current residents get the most free services to our community. out of what our community has to offer. If you are new to the Milwaukee area, please contact We invite you to explore the resources listed in this guide Shalom Milwaukee at the Milwaukee Jewish Federation and to get to know the people behind the organizations (414-390-5700). We are here to help you find a that make our community a rich and relevant place to meaningful Jewish experience in Wisconsin. be Jewish. We hope you will form strong connections, create new opportunities and find your place to thrive. Hannah Rosenthal Daniel Bader CEO/President Chair Connect with your Jewish Community online and in print. For your free subscription contact Tela Bissett at (414) 390-5720 or [email protected]. To advertise, contact Jane Dillon at (414) 390-5765 or [email protected]. JewishChronicle.org Welcome from the Publisher n 1 The Wisconsin Table of Contents WELCOME FROM THE PUBLISHER ................ -

From Rabbi Jessica Barolsky Congregational Picnic, Sunday

HONORING TRADITIONS ENGAGING FAMILIES SUPPORTING COMMUNITIES Volume 92, No. 4 • October 2019 • Tishri/Heshvan 5780 Congregational Picnic, Sunday, September 8 From Rabbi This year’s congregational picnic was a fantastic success! Over 160 people of all Jessica ages attended, including members, prospective members and their wonderful fami - Barolsky lies. There were games, a bounce house, tie-dyeing, BBQ, and so much more. Teachers, Rabbi Barolsky, Cantor Barash and our new Director of Lifelong Learning, As we enter the Susan Cosden, were on hand to greet one and all. Many thanks to all of the many month of October, volunteers and our professional staff who helped bring this wonderful event off. We Yom Kippur is on our are already looking forward to next year’s picnic! minds, as we prepare to gather and atone. Hopefully, we have done the hard work of apologizing to one another for the things we did that we wish we hadn’t— or the things we didn’t do and wish we had. When we come together, we turn toward God, apologizing to God for deeds, words, actions, and inactions between ourselves and the Divine. It is an intense day of prayer and fasting. But it is not the holiday that dominates the upcoming month. Instead, that holiday is Sukkot, the seven-day (or eight-day, depending on your background) harvest festival, the holiday of booths. Sukkot begins this year, on Sunday, October 13, in the evening, but our congregational cele - bration starts the night before. On Saturday night, October 12, we will be having a sukkah decorating party (with thanks to Temple Brotherhood for din - ner and flexibility when the staff asked to take a one-year Sukkahmobile hia - tus). -

Isadore Fine – One Hundred & Counting B'hatzlacha to Our Seniors!

May 2018 Ivvar 5777-Sivan 5778 INSIDE THIS ISSUE Jewish Federation Upcoming Events ................... 5 Camp Corner .................................................10-11 Jewish Social Services ..................................16-19 Simchas & Condolences ...................................... 5 Celebrating Yom HaAtzmaut .........................12-13 Business, Professional & Service Directory ....... 21 Congregation News ...........................................8-9 Jewish Education ................................................ 14 Israel & The World .........................................22-23 Isadore Fine – One Hundred & Counting By Pamela Phillips Olson with additions from Paula Jayne Winnig but deeply impress a person with a sense realized they had it good and behaved. As I sat across from Isadore Fine, her two children back to her husband’s of destiny. When Is was a professor in the business his sharp wit, energy and humor were family’s farm. Unfortunately, she did Is uses himself as a force for good school another punishment surfaced as palpable. Not what you might expect in not receive the warm welcome she had in the world. He has been a devoted a lesson. At age ten, ls worked at his a person about to turn one hundred. He hoped for and realized that she could son, husband, father, grandfather, great- grandfather’s fruit and vegetable wagon. prefers to be called Is Fine which he says not stay with her in- grand father and A lady, wanting potatoes, rejected every is his name and his state of being. laws. teacher. He served -

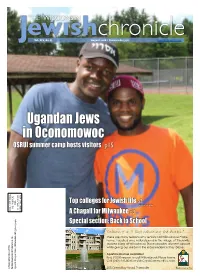

Ugandan Jews in Oconomowoc OSRUI Summer Camp Hosts Visitors P15

Vol. XCV, No. 8 August 2016 • Tammuz-Av 5776 JewishChronicle.org Ugandan Jews in Oconomowoc OSRUI summer camp hosts visitors p15 p3 PAID Top colleges for Jewish life SPECIAL SECTION U.S. POSTAGE MILWAUKEE WI MILWAUKEE PERMIT NO. 5632 NON-PROFIT ORG. A Chagall for Milwaukee p3 Special section: Back to School A free publication of the A free Inc. Milwaukee Jewish Federation, WI 53202-3094 Milwaukee, Ave., N. Prospect 1360 2 • Section I • August 2016 Wisconsin Jewish Chronicle JewishChronicle.org August 2016 • Section I • 3 A GUIDE TO ewish CANDLELIGHTING TIMES J Wisconsin 5777-5778 / 2016-2017 Milwaukee Madison Green Bay Wausau Q uotable A rt A Guide to Jewish Wisconsin August 5 7:49 p.m. 7:55 p.m. 7:53 p.m. 8:01 p.m. * * * * * * Get your FREE copy today! Contact Tela Bissett August 12 7:40 p.m. 7:46 p.m. 7:43 p.m. 7:51 p.m. Local Chagall tied to Israel, “I am standing here and turning to you, “I think the Jewish community should look at (414) 390-5720 • [email protected] Your connection to Jewish Arts, Culture, Education, Camping and Religious Life August 19 7:29 p.m. 7:35p.m. 7:32 p.m. 7:40 p.m. Arab mother. I raised my daughter to love, the big picture. The Democrats, the last eight and you raised your son to hate and sent him years, have not been friends of Israel. Republi- Golda Meir and dreams August 26 7:18 p.m. 7:24 p.m. 7:20 p.m. -

Jewish Wisconsin 5777-5778 / 2016-2017

A GUIDE TO Jewish Wisconsin 5777-5778 / 2016-2017 Your connection to Jewish Arts, Culture, Education, Camping and Religious Life Welcome from the Publisher Thank you for picking up A Guide to Jewish Wisconsin 5777-5778/ 2016-2017. The Guide is designed to help newcomers become acquainted with our state’s vibrant Jewish community and to help current residents get the most out of what our community has to offer. We invite you to explore the resources listed in these pages. Get to know the people and the organizations that make our commu- Andrea Schneider, Board Chair nity a rich and fulfilling place to be Jewish. We hope you will form strong connections, identify new opportunities for explor- ing Judaism and find your place to thrive. The Milwaukee Jewish Federation publishes this guide annually. We also publish The Wisconsin Jewish Chronicle, a monthly newspaper that shares information and fosters a sense of community among Wisconsin Jews. Learn more, and sign up for a free subscription, at JewishChronicle.org. Learn more about the Federation at MilwaukeeJewish.org. (Be sure to check out the community calendar on the home page.) If you are new to the Milwaukee area – or seeking connections to Jewish life – contact Rabbi Hannah Greenstein at (414) 390-5700. We are eager to help you experience Jewish Wisconsin. Hannah Rosenthal, CEO/President Connect with your Jewish Community online and in print. Editor: Rob Golub (414) 390-5770 • [email protected] Free subscription: Tela Bissett (414) 390-5720 • [email protected] To advertise: Jane Dillon (414) 390-5765 • [email protected] JewishChronicle.org MilwaukeeJewish.org n 1 Table of Contents FROM THE PUBLISHER ........................... -

A Guide to Jewish Wisconsin About the Cover—Artist Nancy Kennedy Barnett

WISCONSIN 5781-5782 • 2020-2021 YOUR CONNECTION TO JEWISH ARTS, CULTURE, EDUCATION, CAMPING AND RELIGIOUS LIFE NOW OPEN! New Memory Care Assisted Living Community Stop by to meet our community leadership and see how Silverado is redefining memory care. Silverado delivers world-class care that is recognized for an approach blending compassionNOW andNOW clinical excellence. ACCEPTING OPEN! NOWNOWCall ACCEPTING toNEW schedule ACCEPTING a tour MOVE-INS today NEW NEW MOVE-INS MOVE-INSnorth shore NOW(414) 269-6598 ACCEPTING NEW MOVE-INSmemory care | community NOW ACCEPTING NEW MOVE-INS Silverado NorthNOW Shore - 7800 N GreenOPEN! Bay Rd - Glendale, WI 53217 New Memory Care New Memory Care Assisted Living Community StopAssisted by to meet Living our community Community leadership Stop by to meet our community leadership and see how Silverado is redefining memory andStop see by tohow meet Silverado our community is redefining leadership memory care. Silverado delivers world-class care care.and see Silverado how Silverado delivers is world-class redefining carememory LearnLearnthatLearn about is recognized aboutabout the for the specializedthe an specializedapproach specialized blending care care care Silverado Silverado Silverado provides provides provides thatcare. is Silverado recognized delivers for an world-class approach blending care Newthatcompassion is recognized Memory and clinical for an excellence.approach Care blending for Alzheimer’sforNewcompassionfor Alzheimer’s Memory and clinical and excellence.and andotherCare other other forms forms forms of of dementia. dementia.of dementia. AssistedLearncompassion about and Living clinical the excellence.specialized Community care Silverado provides Stop byStopStop to meet by toto our meetmeet community our our community community leadership leadership leadership and and see and see how howsee Silverado howSilverado Silverado is is redefining redefining is redefining forAssisted Alzheimer’s Living and Community other forms of dementia.north shore memorymemoryCallStopmemory care. -

September-October 2012 • Elul-Cheshvan 5772-5773

SINAI NEWS A bi-monthly publication Issue 11, Volume 1 September-October 2012 • Elul-Cheshvan 5772-5773 Fall Shabbat & Holiday Schedule In this issue Shabbat Ki Tavo Shabbat Ha’ Azinu Rabbi’s Corner, Reflections 2 Deuteronomy 26:1 - 29:8 Deuteronomy 32:1 - 32:52 Sept 7 Shabbat Service 6:15 pm Sept 28 Shabbat Service 6:15 pm Cantorial Soloists, 3 Selichot Sept 29 Torah Study 8 am High Holy Day Cantor, Sept 8 Torah Study 8 am Morning Minyan 9:30 am Director of Youth Education Morning Minyan 9:30 am Dessert Reception 8:30 pm Erev Sukkot From the President 4-5 Selichot Study 9 pm Sept 30 Erev Sukkot Service 6:15 pm Selichot Service 10 pm Sukkot “Scene” at Sinai 5 Shabbat Nitzavim Oct 1 Sukkot Morning Service 9:30 am Deuteronomy 29:9 - 30:20 High Holy Days 6-7 Sept 14 Shabbat Service 6:15 pm Shabbat Chol Hamoed Sukkot Oct 5 Green Shabbat Service 6:15 pm Lifelong Jewish Learning 8-13 Sept 15 Torah Study 8 am Morning Minyan 9:30 am Oct 6 Torah Study 8 am Morning Minyan 9:30 am Membership Committee 14 Erev Rosh Hashanah Joshua Lookatch Bar Mitzvah 10 am Sept 16 Erev Rosh Hashanah Service w/ Board Women at Sinai 15-16 Installation 8 pm Erev Shemini Atzeret & Simchat Torah Oct 7 Simchat Torah Service & Brotherhood, Chesed 17 Rosh Hashanah Consecration 6 pm Sept 17 Morning Service 9:30 am Children’s Service, Tashlich & Shemini Atzeret & Simchat Torah Green Team 18 Shofar Blowing Contest 3 pm Oct 8 Simchat Torah Service 9:30 am Social Action Committee 19 Rosh Hashanah Shabbat Bereshit Sept 18 2nd Day Breakfast & Study Genesis 1:1 - 6:8 Session 9:30 -

Combined Lockdown Report

KEY AIMS DELIVER UNIQUE BENEFITS TO OUR AUDIENCES AND COMMUNITIES WORK TOWARDS FINANCIAL RESILIENCE CAPITALISE ON THE SKILLS, NETWORKS AND SYSTEMS WITHIN THE JEWISH MUSEUM LONDON POSITION THE MUSEUM WELL INTO THE ‘NEW NORMAL’ LOCKDOWN IMPACT REPORT Part 1: March–August 2020, Part 2: September 2020 - March 2021 OUR ACHIEVEMENTS THROUGHOUT THE YEAR Since the start of the national Lockdown the Museum has gone through Virtual Tours and Events a lot of changes, including pivoting our resources to create a digital museum experience. Throughout this time we have prioritised providing the best possible learning experience, continuing to engage with our 21 community and partners, and utilising our collection. We are so proud of the incredible successes we've been able to achieve, and the skills, 6 25 creativity, and resourcefulness of our whole team. EXCLUSIVE EVENTS Schools and Learning TOURS ON ROTATION FOR FRIENDS AND PATRONS PUBLIC TOURS AND EVENTS 6,790 6,462 1,830 4 1,700 15 STUDENTS ATTENDED STUDENTS VISITED OUR STUDENTS INTERACTED FACILITATED SESSIONS VIRTUAL CLASSROOMS WITH OUR MUSEUM IN A BOX ENGAGEMENT OF OVER 1,700 CURIOUS MINDS DEMENTIA CURIOUS EXPLORERS PEOPLE FOR OUR PUBLIC EVENTS FRIENDLY WORKSHOPS AUTISM FRIENDLY SESSIONS 56 Livestreamed Events Behind The Scenes 10 48,852 CPD SESSIONS FOR TEACHERS TEACHERS ATTENDED OUR USERS ON OUR ONLINE TEACHERS' TEACHERS PORTAL CPD SESSIONS 163 300 17,000 Digital Engagement NEARLY 17,000 PEOPLE VIDEOS RELEASED VIEWED OUR OBJECT TALKS NEARLY 300 COLLECTION SUBSCRIBE REQUESTS WERE ANSWERED LIVE 17,000 NEW NEARLY 17,000 PEOPLE NEARLY 1,000 OVER 119,000 3,386 VIEWED OUR FAMILIES OVER 19,000 NEW TWITTER FOLLOWERS REACH OF FACEBOOK POSTS NEW YOUTUBE SUBSCRIBERS LIVE MUSEUM MORNINGS ACTIVITY PACKS 2 Lockdown Impact Report Combined Stats jewishmuseum.org.uk 3 Contents MEET THE TEAM 2 Meet the Team Change in Leadership at the Museum Welcome from Nick Viner, Chair of Trustees Trustees Staff Schools and Teachers The last few months have been incredibly Jamie Beaumont challenging for all of us. -

Madison Jewish News 4

October 2016 Tishrei, 5777 A Publication of the Jewish Federation of Madison INSIDE THIS ISSUE Jewish Federation Upcoming Events ......................5 Tzedakah Campaign Kickoff in Pictures ..........14-15 Jewish Education ..........................................20-21 Congregation News ..........................................8-9 Rosh Hashanah Greeting & HHD Schedule......16-17 Jewish Social Services....................................22-24 Simchas & Condolences ......................................11 Business, Professional & Service Directory ............19 Israel & The World ........................................26-27 Time to Celebrate the 2016 Tzedakah Campaign Editor’s note: On Sunday, September was run by a dynamic leadership duo that Federation’s board and was incredibly im- 11th, 2016, the community gathered at inspired Jewish students to be active on pressed. The board asked so many Full Compass to celebrate the 2016 campus and in the greater Madison com- thoughtful, smart questions. I have worked Tzedakah Campaign Kickoff. This spe- munity. This couple inspired me to re- with many non-profit boards before and cial evening was filled with delicious evaluate how important Judaism was to after that. I have never worked with one food, wonderful music, and information me from a spiritual perspective and from that asked so many questions…so, so about the local and worldwide needs a cultural perspective. If you think this duo many. The engagement of board members funded by the Jewish Federation of might sound familiar to you, it probably was, and continues to be, a hallmark of the Madison. Below is an address given by does. Greg and Rabbi Andrea Steinberger Federation. People on our board really Joe Shumow, Vice President of the Jewish are directly responsible for my initial in- care about Jewish life in Madison and Federation of Madison. -

Judaism-Faqs.Pdf

Frequently Asked Questions about Judaism Thank you for visiting the Jewish Museum Milwaukee website. Our visitors often have questions about Judaism, so we have compiled a short list of questions and answers that you may find of interest. Questions are central to Jewish life, and Jews never really stop questioning. The answers provided below are just a glimpse of Jewish belief, and we urge you to consult more sources to learn even more answers to your questions. Please feel free to email us with more questions and feedback at [email protected] LAWS AND CUSTOMS Q: What is the Torah? A: The Torah is the central book of the Jewish people. According to tradition, the Torah was given to the Jews from God on Mount Sinai. The Torah contains the history of the Jewish people, traditions and laws. Sometimes the Torah is called the “Tree of Life.” There are five books of the Torah: B’reshit - Genesis “In the beginning” Sh’mot - Exodus “The names of...” Vayyikra - Leviticus “...called” Bemidbar - Numbers “In the wilderness” D’varim - Deuteronomy “The words” Q: What is Jewish law? A: Jewish law is complicated because not all of the rules followed by Jews today are clearly written in the Torah. Instead, many laws are the interpretations of the Torah by scholarly rabbis. These interpretations are written in the Talmud, which is still studied and analyzed along with the Torah today. Therefore, when the term “Jewish law” is used, it does not necessarily equal “Biblical law.” Q: What does Shabbat Shalom mean? A: Shabbat Shalom is a common Shabbat greeting among Jews. -

BE Class 4 Column

JEWISH FEDERATION OF MADISON September 2013 Tishrei 5774 Inside This Issue Jewish Federation Upcoming Events ......................5 Jewish Education ..........................................10-11 Business, Professional & Service Directory ............24 Simchas & Condolences ........................................6 Jewish Social Services....................................18-20 Rosh Hashanah Greetings........................25-29, 32 Congregation News ..........................................8-9 Lechayim Lights ............................................21-23 Israel & The World ........................................34-35 Lynn Kaplan Named Passport to Jewish Life Financial Resource $500 Available to Eligible Households The Passport Gift can be used towards programs or organizations Development Director such as, but not limited to: • Gan HaYeled Preschool BY DINA WEINBACH The Jewish Federation of Madison • Chug Ivrit (JFM) is excited to announce the Passport • Camp Shalom Executive Director to Jewish Life Program! Thanks to gener- • Midrasha We are thrilled to announce that Lynn ous private donations, this exciting pro- • Yonim Kaplan has been named the Financial gram is aimed at engaging community • Madison Jewish Community Day Resource Development Director for the members in the wonderful programs the School Jewish Federation of Madison. Lynn has Madison-area Jewish community has to • Introductory synagogue membership been working at the Jewish Federation offer. Individuals or families in the Madi- fees of Madison (JFM) since 1999. Prior to son-area who meet the following criteria • Madison-area adult Jewish Education her employment, Lynn graduated from are eligible for a gift of up to $500 (one programs (e.g. offered by synagogues, the JFM Future Directions Young Lead- gift per household) to be used for tuition UW, Hillel, Chabad, etc.) ership Program, chaired the Hava Nagila or fees at Madison-area Jewish programs The Passport Gift cannot be used Jewish Community Picnic committee, (see examples below).