CIPLA, Ltd. CIPLA Ltd Is a Pharmaceutical Company Based in India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Investor Presentation May 2016

Investor Presentation May 2016 BSE: 532523 │ NSE: BIOCON │ REUTERS: BION.NS │ BLOOMBERG: BIOS IN │ WWW.BIOCON.COM Safe Harbor Certain statements in this release concerning our future growth prospects are forward-looking statements, which are subject to a number of risks, uncertainties and assumptions that could cause actual results to differ materially from those contemplated in such forward-looking statements. Important factors that could cause actual results to differ materially from our expectations include, amongst others general economic and business conditions in India, our ability to successfully implement our strategy, our research and development efforts, our growth and expansion plans and technological changes, changes in the value of the Rupee and other currencies, changes in the Indian and international interest rates, change in laws and regulations that apply to the Indian and global biotechnology and pharmaceuticals industries, increasing competition in and the conditions of the Indian biotechnology and pharmaceuticals industries, changes in political conditions in India and changes in the foreign exchange control regulations in India. Neither the company, nor its directors and any of the affiliates have any obligation to update or otherwise revise any statements reflecting circumstances arising after this date or to reflect the occurrence of underlying events, even if the underlying assumptions do not come to fruition. 2 Agenda Biocon: Who are we? Highlights • Business Highlights • Financial Highlights Growth Segments • -

Cipla Ltd (CIPLA)

Cipla Ltd (CIPLA) CMP: | 826 Target: | 975 (18%) Target Period: 12 months BUY January 30, 2021 Strong growth in India, RoW; better margins… Q3 revenues grew 18.2% YoY to | 5169 crore led by strong growth in domestic and RoW markets. Domestic sales grew 25.5% YoY to | 2231 crore. RoW markets business grew 47.2% YoY to | 823 whereas South Particulars Africa business fell 2.5% YoY to | 579 crore. US grew 9.6% YoY to | 1037 crore. EBITDA margins expanded 647 bps YoY to 23.8% mainly due to P articular Am ount significantly lower other expenditure. Hence, EBITDA grew 62.3% YoY to | Market Capitalisation | 66581 crore 1231 crore. PAT more than doubled to | 748 crore vs. | 351 crore in Q3FY20. Debt (FY20) | 2816 crore Cash (FY20) | 1004 crore Result Update Result Product launches, front-end shift key for formulation exports E V | 68393 crore 52 week H/L (|) 870/357 Formulation exports comprise ~54% of FY20 revenues. The company is E quity capital | 161.3 crore focusing on front-end model, especially for the US, along with a gradual shift from loss making HIV and other tenders to more lucrative respiratory and F ace value | 2 Price performance other opportunities in the US and EU. We expect export formulation sales to grow at 9.8% CAGR to | 12242 crore in FY20-23E. Key drivers will be a launch of inhalers (drug-device) and other products in developed markets. 1000 14000 12000 800 Indian formulations growth backed by new launches 10000 600 8000 With ~5% market share, Cipla is the third largest player in the domestic 400 6000 formulations market. -

Domestic Institutional Philanthropy in India

Charting a course post COVID-19 Supported by Delivering High Impact SEP 2020 Published by Sattva in September 2020. Supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Email [email protected] Website www.sattva.co.in Lead Researchers Aarti Mohan, Sanjana Govil, Bhavin P Chhaya Research, Analysis Prachur Goel, Shalini Rajan, and Production Mansi Agarwal, Palagati Lekhya Reddy, Ashwini Rajkumar, Radhika Bose, Gayatri Malhotra, Brooke VanSant, Anushka Bhansali Project Advisors Karuna Segal, Arnav Kapur, Anjani Kumar Singh (Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation), Srikrishna Sridhar Murthy (Sattva Consulting) Design and Bhakthi Dakshinamurthy Typesetting [email protected] Cover Photo Axis Bank Foundation We are grateful to 74 leaders representing 47 organisations in the domestic institutional philanthropy ecosystem who generously shared their expertise and insights for this report (See Annexure 3 for a complete List of Interviews). This work is licensed under the Attribution-Non Commercial-ShareALike 4.0 International License: Attribution - You may give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if any changes were made. NonCommercial - You may not use the material for commercial purposes. ShareALike - If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original. About this study 01 Introduction 04 Executive summary 06 The landscape before and after COVID-19 08 Trends in intervention strategies 15 Trends in programme implementation 20 Programme trends per sector 27 Agricultural livelihoods Water and sanitation Women’s empowerment and digital financial inclusion Health systems and delivery Approaches to scale and collaboration 36 Annexures 41 Explanation of terms Study scope and methodology List of interviews Endnotes About 51 Dr. -

Cipla Limited

Cipla Limited Registered Office: Cipla House, Peninsula Business Park, Ganpatrao Kadam Marg, Lower Parel, Mumbai – 400 013 Phone: (9122) 2482 6000, Fax: (9122) 2482 6893, Email: [email protected], Website: www.cipla.com Corporate Identity Number: L24239MH1935PLC002380 Annexure to the Board’s Report Particulars of employee remuneration for the financial year ended 31st March, 2019 As required under section 197(12) of the Companies Act, 2013, read with rule 5(2) and (3) of the Companies (Appointment and Remuneration of Managerial Personnel) Rules, 2014. Employed throughout the year Name Designation Qualification Experience Age Date of Last employment Remuneration (in years) (in years) Employment (Rs.) Abhay Kumar Chief Talent Officer Master of Arts / 17 53 3/10/2016 Piramal Pharma 15,034,298.00 Srivastava Master of Personal Solutions Management Ademola Olukayode Head - Quality Doctorate / MPH / B. 17 48 20/6/2018 US FOOD AND DRUG 17,982,961.00 Daramola Compliance & Tech. ADMINISTRATION Sustainability (US FDA) Ajay Luharuka Head Finance - IPD, B.com,MMS,CFA 23 46 11/7/1996 NIIT Limited 11,922,994.00 API, Specialty & Global Respi Aliakbar Rangwala Senior Business Head M. Sc. / B. Sc. 19 42 19/1/2009 NA 10,677,779.00 - Chronic & Emerging - India Business Alpana Vartak Head - Talent MBA (HR) / B. Sc. 15 41 8/1/2018 Coco - Cola 10,312,782.00 Acquisition Company Anil Kartha Site Head - Bsc, Bpharm 28 56 27/5/1991 Vysali 12,525,338.00 Patalganga - Pharmaceuticals Formulations Anindya Kumar Shee Head - Organization B. Tech. / MBA 18 48 14/1/2016 Reliance Industries 11,084,298.00 Development Ltd. -

Business Organizations

CHAPTER 3 BUSINESS ORGANIZATIONS LEARNING OUTCOMES After studying this unit, you will be able to: w Have an overview of corporate history of some of the selected Indian and Global companies. w Gain information about management teams of selected companies. w Know the vision, mission and core values of dierent companies. w Know the market and nancial performance of dierent companies. w Gain vital information on products and services of famous brands of dierent companies. w Analyse a company’s information as a business analyst. © The Institute of Chartered Accountants of India ICAI _ICAI_Business and Commercial Konwledge_Chp_03-nw.indd 1 7/27/2017 3:53:35 PM 3.2 BUSINESS AND COMMERCIAL KNOWLEDGE CHAPTER OVERVIEW OVERVIEW OF SELECTED COMPANIES INDIAN COMPANIES GLOBAL COMPANIES • Adani Ports and Special Economic Zone Ltd. • Deutsche Bank • Asian Paints Ltd. • American Express • Axis Bank Ltd. • Nestle • Bajaj Auto Ltd. • Microsoft Corporation • Bharti Airtel Ltd. • IBM Corporation • Bharat Petroleum Corporation Ltd. • Intel Corporation • Cipla Ltd. • HP • Coal India Ltd. • Apple • Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories Ltd. • Walmart • GAIL (India) Ltd. • HDFC Bank Ltd. • ICICI Bank Ltd. • Indian Oil Corporation Ltd. • Infosys Ltd. • ITC Ltd. • Larsen & Toubro Ltd. • NTPC Ltd. • Oil & Natural Gas Corporation Ltd. • Power Grid Corporation of India Ltd. • Reliance Industries Ltd. • State Bank of India • Tata Sons Limited • Wipro Ltd. © The Institute of Chartered Accountants of India ICAI _ICAI_Business and Commercial Konwledge_Chp_03-nw.indd 2 7/27/2017 3:53:35 PM BUSINESS ORGANIZATIONS 3.3 3.1 INTRODUCTION A company overview is the most eective way to acquire business intelligence and gain vital information about a company, its businesses, their products, services and processes, prospects, customers, suppliers, competitors; etc. -

List of Nodal Officer

List of Nodal Officer Designa S.No tion of Phone (With Company Name EMAIL_ID_COMPANY FIRST_NAME MIDDLE_NAME LAST_NAME Line I Line II CITY PIN Code EMAIL_ID . Nodal STD/ISD) Officer 1 VIPUL LIMITED [email protected] PUNIT BERIWALA DIRT Vipul TechSquare, Golf Course Road, Sector-43, Gurgaon 122009 01244065500 [email protected] 2 ORIENT PAPER AND INDUSTRIES LTD. [email protected] RAM PRASAD DUTTA CSEC BIRLA BUILDING, 9TH FLOOR, 9/1, R. N. MUKHERJEE ROAD KOLKATA 700001 03340823700 [email protected] COAL INDIA LIMITED, Coal Bhawan, AF-III, 3rd Floor CORE-2,Action Area-1A, 3 COAL INDIA LTD GOVT OF INDIA UNDERTAKING [email protected] MAHADEVAN VISWANATHAN CSEC Rajarhat, Kolkata 700156 03323246526 [email protected] PREMISES NO-04-MAR New Town, MULTI COMMODITY EXCHANGE OF INDIA Exchange Square, Suren Road, 4 [email protected] AJAY PURI CSEC Multi Commodity Exchange of India Limited Mumbai 400093 0226718888 [email protected] LIMITED Chakala, Andheri (East), 5 ECOPLAST LIMITED [email protected] Antony Pius Alapat CSEC Ecoplast Ltd.,4 Magan Mahal 215, Sir M.V. Road, Andheri (E) Mumbai 400069 02226833452 [email protected] 6 ECOPLAST LIMITED [email protected] Antony Pius Alapat CSEC Ecoplast Ltd.,4 Magan Mahal 215, Sir M.V. Road, Andheri (E) Mumbai 400069 02226833452 [email protected] 7 NECTAR LIFE SCIENCES LIMITED [email protected] SUKRITI SAINI CSEC NECTAR LIFESCIENCES LIMITED SCO 38-39, SECTOR 9-D CHANDIGARH 160009 01723047759 [email protected] 8 ECOPLAST LIMITED [email protected] Antony Pius Alapat CSEC Ecoplast Ltd.,4 Magan Mahal 215, Sir M.V. Road, Andheri (E) Mumbai 400069 02226833452 [email protected] 9 SMIFS CAPITAL MARKETS LTD. -

Pharma Majors Collaborate for Clinical Trial of Investigational Oral Anti-Viral Drug Molnupiravir for COVID-19

Pharma Majors Collaborate for Clinical Trial of Investigational Oral Anti-Viral Drug Molnupiravir for COVID-19 Cipla, Dr. Reddy’s, Emcure, Sun Pharma and Torrent to collaborate for clinical trial of investigational anti-viral drug Molnupiravir for COVID-19 India. June 29, 2021 - Cipla Limited (BSE: 500087; NSE: CIPLA EQ, referred to as “Cipla”), Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories Ltd. (BSE: 500124, NSE: DRREDDY, NYSE: RDY, NSEIFSC: DRREDDY, hereafter referred to as “Dr. Reddy’s”), Emcure Pharmaceuticals Limited (hereafter referred to as “Emcure”), Sun Pharmaceutical Industries Limited (Reuters: SUN.BO, Bloomberg: SUNP IN, NSE: SUNPHARMA, BSE: 524715, “Sun Pharma” and includes its subsidiaries and/or associate companies), and Torrent Pharmaceuticals Limited (“Torrent”, BSE: 500420, NSE: TORNTPHARM), announced today that the five companies will collaborate for the clinical trial of the investigational oral anti-viral drug Molnupiravir for the treatment of mild COVID-19 in an outpatient setting in India. Between March and April this year, these five pharma companies had individually entered into a non-exclusive voluntary licensing agreement with Merck Sharpe Dohme (MSD) to manufacture and supply Molnupiravir to India and over 100 low and middle-income countries (LMICs). The five pharma companies have entered into a collaboration agreement, wherein the parties will jointly sponsor, supervise and monitor the clinical trial in India. As per the directive of the Subject Expert Committee (SEC) of the Central Drugs Standard Control Organization, Dr. Reddy’s will conduct the clinical trial using its product, and the other four pharma companies will be required to demonstrate equivalence of their product to the product used by Dr. -

IR Magazine Awards – India 2019 Winners and Nominees

IR Magazine Awards – India 2019 Winners and nominees Best financial reporting (large cap) Cipla Hindalco Industries Hindustan Unilever Infosys Kotak Mahindra Bank Mahindra & Mahindra WINNER Piramal Enterprises Tata Steel Vedanta Best financial reporting (small to mid-cap) CEAT Everest Industries Hikal Hindustan Foods IIFL Finance KEC International Minda Industries Raymond WINNER The Phoenix Mills Zensar Technologies Best investor meetings (large cap) Bharti Airtel Hindustan Unilever WINNER Infosys Lupin Mahindra & Mahindra Piramal Enterprises Best investor meetings (mid-cap) Balkrishna Industries WINNER IIFL Finance Mindtree RPG Group Sterlite Technologies The Phoenix Mills IR Magazine Awards – India 2019 Winners and nominees Best investor meetings (small cap) Amber Enterprises India Equitas Holdings Greenlam Industries Music Broadcast WINNER Navin Fluorine International NOCIL Raymond Zensar Technologies Best investor relations officer (large cap) Bharti Airtel Komal Sharan WINNER Bharti Airtel Aparna Vyas Garg Bharti Infratel Surabhi Chandna Cipla Naveen Bansal HDFC Conrad D'Souza Hindustan Unilever Suman Hegde Infosys Sandeep Mahindroo Kotak Mahindra Bank Nimesh Kampani Lupin Arvind Bothra Best investor relations officer (small to mid-cap) CEAT Pulkit Bhandari Jindal Steel & Power Nishant Baranwal Motilal Oswal Financial Services Rakesh Shinde PNB Housing Finance Deepika Gupta Padhi Raymond J Mukund RPG Group Pulkit Bhandari Schneider Electric Infrastructure Vineet Jain The Phoenix Mills Varun Parwal WINNER Best investor relations team -

Sharekhan Special August 31, 2021

Sharekhan Special August 31, 2021 Index Q1FY2022 Results Review Automobiles • Capital Goods • Consumer Discretionary • Consumer Goods • Infrastructure/Cement/Logistics/Building Material • IT • Oil & Gas • Pharmaceuticals • Agri Inputs and Speciality Chemical • Miscellaneous • Visit us at www.sharekhan.com For Private Circulation only Q1FY2022 Results Review In-line quarter, healthy outlook Results Review Results Summary: After ending FY2021 on a strong note, Q1FY2022 earnings of broader indices showed a promising start (Nifty/ Sensex companies’ PAT rose 100%/66% y-o-y) in the new fiscal with strong growth momentum on low base. Management commentaries on earnings outlook remained positive, on improving economic activity post second COVID-19 wave and anticipation of strong demand revival. Demand recovery and ramp-up of vaccinations look encouraging. We expect economic activity to increase in the upcoming festive season. Nifty trades at 23x and 20x EPS based on FY2022E/FY2023E EPS, at a premium to mean average. Valuation gap between large and mid-caps has shrunk, we advise investors to focus on stocks with strong earnings growth potential with reasonable valuation. High-conviction investment ideas: o Large-caps: Infosys, ICICI Bank, M&M, L&T, UltraTech, SBI, HDFC Ltd, Godrej Consumer Products, Divis Labs and Titan. o Mid-caps: NAM India, BEL, Gland Pharma, Dalmia Bharat, Laurus Labs, Max Financial Services, LTI. o Small-caps: TCI Express, Kirloskar Oil, Suprajit Engineering, Repco Home Finance, PNC Infratech, Mahindra Lifespaces, Birlasoft. After ending FY2021 on a strong note, Q1FY2022 corporate earnings of broader indices showed a promising start with continued strong growth momentum on the low base of Q1FY2021, though it was along the expected lines. -

Tata Consultancy Services Ltd

The Institution TATA CONSULTANCY SERVICES LTD. (PROFORMA FOR ACCREDITATION DEENBANDHU WITH CHHOTU THE TCS) RAM UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE & INSTITUTETECHNOLOGY PROFILE DATED:Name 25.07.2011 of the Institution (STATE UNIVERSITY OF HARYANA 1.1 GOVT.) VPO MURTHAL, DISTT. SONEPAT Postal Address (HARYANA) PIN CODE- 131039 1.2 Contact Person 1.3 Name DR. VIRENDER AHLAWAT Designation TRAINING & PLACEMENT OFFICER Mobile 9416342915 Landline with Station Code 130-2484129 [email protected] & Email [email protected] Principal/ Registrar Registrar 1.4 Name Sh. R. K. Arora Mobile Landline with station code 0130-2484005 Email [email protected] Chairman/ Vice Chancellor VICE CHANCELLOR 1.5 Name SH H.S. CHAHAL Mobile 9416067400 Landline with Station code 0130-2484003 Email [email protected] Nearest Airport/ Railway Station IGI AIRPORT, NEW DELHI 1.6 RAILWAY STATION:- SONEPAT C.R.State College of Engg. Murthal (1987) morphed into the Deenbandhu Chhotu Ram Year of Establishment University of Science & Technology on 1.7 NOVEMEBER, 2006 Govt University/Deemed/University Affiliated Govt College/ Affiliated Private College/ Status (Please Color whichever applicable) Autonomous /Govt aided Private College 1.8 University Grant Commission Under Section University to which affiliated 12(B), of UGC Act 1956 1.9 Approved by AICTE YES 1.10 Accredited by NBA NO 1.11 Are you ISO certified, if so details NO 1.12 To facilitate and promote studies and research in emerging areas of higher education with focus on new frontiers of Science, Engineering, Technology, Architecture and Management, Please state your Vision Statement leading to evolution of enlightened technocrats, innovators, scientists, leaders and entrepreneurs who will contribute to national growth in particular and to international community as a whole. -

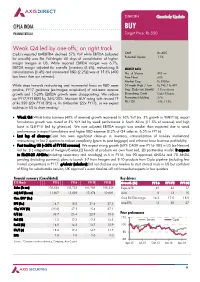

Weak Q4 Led by One-Offs; on Right Track

25 MAY 2016 Quarterly Update CIPLA INDIA BUY PHARMACEUTICALS Target Price: Rs 550 Weak Q4 led by one-offs; on right track Cipla’s reported Q4EBITDA declined 57% YoY while EBITDA (adjusted CMP : Rs 495 Potential Upside : 11% for one-offs) was flat YoYdespite 40 days of consolidation of higher- margin Invagen in US. While reported EBITDA margin was 6.7%, EBITDA margin adjusted for one-offs [inventory (3.4%), restructuring & MARKET DATA rationalization (3.4%) and incremental R&D (2.2%)] was at 15.8% (400 No. of Shares : 803 mn bps lower than our estimate). Free Float : 63% Market Cap : Rs 398 bn While steps towards restructuring and incremental focus on R&D seem 52-week High / Low : Rs 748 / Rs 492 positive, FY17 guidance (ex-Invagen acquisition) of mid-teens revenue Avg. Daily vol. (6mth) : 1.8 mn shares growth and 15-20% EBITDA growth seem disappointing. We reduce Bloomberg Code : Cipla IB Equity our FY17/FY18EPS by 26%/20%. Maintain BUY rating with revised TP Promoters Holding : 37% FII / DII : 14% / 15% of Rs 550 (20x FY18 EPS) vs. Rs 640earlier (22x FY17), as we expect scale-up in US to drive rerating. ♦ Weak Q4:While India business (40% of revenue) growth recovered to 16% YoY (vs. 3% growth in 9MFY16), export formulation growth was muted at 3% YoY led by weak performance in South Africa (11.5% of revenue) and high base in Q4FY15 (led by gNexium). We note adjusted EBITDA margin was weaker than expected due to weak performance in export formulations and higher R&D expense (8.2% of Q4 sales vs. -

Momentum Pick

Momentum Picks Open Recommendations New recommendations Gladiator Stocks Date Scrip I-Direct Code Action Initiation Range Target Stoploss Duration 1-Oct-21 Nifty Nifty Sell 17520-17545 17482/17430 17583.00 Intraday Scrip Action 1-Oct-21 ONGC ONGC Buy 142.50-143.00 144.25/145.70 141.20 Intraday Hindalco Buy PICK MOMENTUM 1-Oct-21 UPL UPL Sell 707.00-708.00 700.60/693.80 714.60 Intraday Bata India Buy 30-Sep-21 Trent TRENT Buy 1010-1025 1125 948.00 30 Days HDFC Buy 30-Sep-21 Dhampur Sugar DHASUG Buy 290-294 312 282.00 07 Days Duration: 3 Months Click here to know more… Open recommendations Date Scrip I-Direct Code Action Initiation Range Target Stoploss Duration 29-Sep-21 SJVN SJVLIM Buy 28.3-29 31.50 27.00 14 Days 29-Sep-21 National Aluminium NATALU Buy 92-94 101.00 86.50 07 Days Intraday recommendations are for current month futures. Positional recommendations are in cash segment Retail Equity Research Retail – October 1, 2021 For Instant stock ideas: SUBSCRIBE to mobile notification on ICICIdirect Mobile app… Research Analysts Securities ICICI Dharmesh Shah Nitin Kunte, CMT Ninad Tamhanekar, CMT [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Pabitro Mukherjee Vinayak Parmar [email protected] [email protected] NSE (Nifty): 17618 Technical Outlook NSE Nifty Daily Candlestick Chart Domestic Indices Day that was… Open High Low Close Indices Close 1 Day Chg % Chg Equity benchmarks concluded the monthly expiry session on a subdued note tracking mixed global cues.