The Relative Age Effect Reversal Among the National Hockey League Elite1 Luca Fumarco2, Benjamin G. Gibbs3, Jonathan A. Jarvis3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BOSTON BRUINS Vs. TAMPA BAY LIGHTNING

BOSTON BRUINS vs. TAMPA BAY LIGHTNING POST GAME NOTES MILESTONES REACHED: • Charlie Coyle played his 500th NHL game today. • Tampa Bay’s Anthony Cirelli played his 100th NHL game today. WHO’S HOT: • David Krejci had a goal and an assist today, giving him 1-8=9 totals in five of his last six games with 5-13=18 totals in 12 of his last 16 contests ... It was his 20th goal of the season, the fourth 20-goal season of his career, and gives Boston five 20-goal scorers (Pastrnak, Marchand, Bergeron, DeBrusk, Krejci) for the first time since 2013-14. • David Pastrnak had two assists today, giving him 7-8=15 totals in seven of his last nine games with 11-15=26 totals in 14 of his last 17 games played. • Danton Heinen had a goal today, giving him 2-3=5 totals in four of his last nine games. • Matt Grzelcyk had a goal today, giving him 2-2=4 totals in four of his last eight games played. • Charlie McAvoy had an assist today, giving him 1-2=3 totals in three of his last five games. • Steven Kampfer had an assist today, giving him 1-2=3 totals in three of his last five games played. • Tampa Bay’s Braydon Coburn had a goal and an assist today, giving him 1-3=4 totals in two of his last four games. • Tampa Bay’s Anthony Cirelli had a goal and an assist today, giving him 5-4=9 totals in seven of his last 11 games. -

Weekly Champ List

Tied First Place Super Draft teams 1 BGRANT6 2235pts 2 REDLIGHRAIDERS6 2235pts Daniel Sedin (LW) VAN 104 Daniel Sedin (LW) VAN 104 Martin St. Louis (RW) TB 99 Martin St. Louis (RW) TB 99 Corey Perry (RW) ANA 98 Corey Perry (RW) ANA 98 Henrik Sedin (C) VAN 94 Henrik Sedin (C) VAN 94 Steven Stamkos (C) TB 91 Steven Stamkos (C) TB 91 Jarome Iginla (RW) CGY 86 Jarome Iginla (RW) CGY 86 Alex Ovechkin (LW) WAS 85 Alex Ovechkin (LW) WAS 85 Henrik Zetterberg (LW) DET 80 Henrik Zetterberg (LW) DET 80 Brad Richards (C) DAL 77 Brad Richards (C) DAL 77 Ryan Getzlaf (C) ANA 76 Ryan Getzlaf (C) ANA 76 Jonathan Toews (C) CHI 76 Jonathan Toews (C) CHI 76 Eric Staal (C) CAR 76 Eric Staal (C) CAR 76 Thomas Vanek (LW) BUF 73 Claude Giroux (RW) PHI 76 Patrick Marleau (LW) SJ 73 Patrick Marleau (LW) SJ 73 Patrick Kane (RW) CHI 73 Patrick Kane (RW) CHI 73 Loui Eriksson (RW) DAL 73 Loui Eriksson (RW) DAL 73 Anze Kopitar (C) LA 73 Anze Kopitar (C) LA 73 Bobby Ryan (LW) ANA 71 Joe Thornton (C) SJ 70 Joe Thornton (C) SJ 70 Danny Briere (RW) PHI 68 Sidney Crosby (C) PIT 66 John Tavares (C) NYI 67 Rick Nash (RW) CBJ 66 Sidney Crosby (C) PIT 66 Mike Richards (C) PHI 66 Mike Richards (C) PHI 66 Jeff Carter (RW) PHI 66 Nicklas Backstrom (C) WAS 65 Nicklas Backstrom (C) WAS 65 Phil Kessel (RW) TOR 64 Phil Kessel (RW) TOR 64 Dany Heatley (RW) SJ 64 Dany Heatley (RW) SJ 64 Mikko Koivu (C) MIN 62 Ilya Kovalchuk (RW) NJ 60 Ilya Kovalchuk (RW) NJ 60 Pavel Datsyuk (LW) DET 59 Pavel Datsyuk (LW) DET 59 Paul Stastny (C) COL 57 Paul Stastny (C) COL 57 Alexander Semin (RW) WAS -

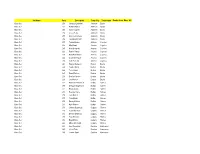

Set Name Card Description Team City Team Name Rookie Auto

Set Name Card Description Team City Team Name Rookie Auto Mem #'d Base Set 251 Hampus Lindholm Anaheim Ducks Base Set 252 Rickard Rakell Anaheim Ducks Base Set 253 Sami Vatanen Anaheim Ducks Base Set 254 Corey Perry Anaheim Ducks Base Set 255 Antoine Vermette Anaheim Ducks Base Set 256 Jonathan Bernier Anaheim Ducks Base Set 257 Tobias Rieder Arizona Coyotes Base Set 258 Max Domi Arizona Coyotes Base Set 259 Alex Goligoski Arizona Coyotes Base Set 260 Radim Vrbata Arizona Coyotes Base Set 261 Brad Richardson Arizona Coyotes Base Set 262 Louis Domingue Arizona Coyotes Base Set 263 Luke Schenn Arizona Coyotes Base Set 264 Patrice Bergeron Boston Bruins Base Set 265 Tuukka Rask Boston Bruins Base Set 266 Torey Krug Boston Bruins Base Set 267 David Backes Boston Bruins Base Set 268 Dominic Moore Boston Bruins Base Set 269 Joe Morrow Boston Bruins Base Set 270 Rasmus Ristolainen Buffalo Sabres Base Set 271 Zemgus Girgensons Buffalo Sabres Base Set 272 Brian Gionta Buffalo Sabres Base Set 273 Evander Kane Buffalo Sabres Base Set 274 Jack Eichel Buffalo Sabres Base Set 275 Tyler Ennis Buffalo Sabres Base Set 276 Dmitry Kulikov Buffalo Sabres Base Set 277 Kyle Okposo Buffalo Sabres Base Set 278 Johnny Gaudreau Calgary Flames Base Set 279 Sean Monahan Calgary Flames Base Set 280 Dennis Wideman Calgary Flames Base Set 281 Troy Brouwer Calgary Flames Base Set 282 Brian Elliott Calgary Flames Base Set 283 Micheal Ferland Calgary Flames Base Set 284 Lee Stempniak Carolina Hurricanes Base Set 285 Victor Rask Carolina Hurricanes Base Set 286 Jordan -

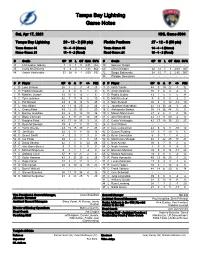

Tampa Bay Lightning Game Notes

Tampa Bay Lightning Game Notes Sat, Apr 17, 2021 NHL Game #694 Tampa Bay Lightning 29 - 12 - 2 (60 pts) Florida Panthers 27 - 12 - 5 (59 pts) Team Game: 44 16 - 4 - 0 (Home) Team Game: 45 14 - 4 - 3 (Home) Home Game: 21 13 - 8 - 2 (Road) Road Game: 24 13 - 8 - 2 (Road) # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% 33 Christopher Gibson 1 0 1 0 4.41 .765 30 Spencer Knight - - - - - - 35 Curtis McElhinney 9 3 5 1 3.48 .862 60 Chris Driedger 20 12 5 3 2.09 .927 88 Andrei Vasilevskiy 33 26 6 1 2.00 .932 72 Sergei Bobrovsky 24 15 7 2 2.85 .907 95 Philippe Desrosiers - - - - - - # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM 2 D Luke Schenn 26 1 2 3 -4 23 3 D Keith Yandle 44 3 19 22 -7 32 3 D Fredrik Claesson 4 0 0 0 1 0 6 D Anton Stralman 35 3 6 9 -4 8 7 R Mathieu Joseph 43 10 6 16 7 6 7 D Radko Gudas 43 1 5 6 5 31 9 C Tyler Johnson 42 7 11 18 2 10 8 D Matt Kiersted 5 0 0 0 -2 2 14 L Pat Maroon 43 4 14 18 5 48 9 C Sam Bennett 38 4 8 12 -14 19 17 L Alex Killorn 43 11 14 25 2 26 11 L Jonathan Huberdeau 44 14 30 44 -3 24 18 L Ondrej Palat 43 12 23 35 1 20 16 C Aleksander Barkov 38 18 26 44 12 8 19 C Barclay Goodrow 43 6 9 15 10 36 19 L Mason Marchment 27 2 6 8 4 16 20 C Blake Coleman 42 8 13 21 12 29 21 C Alex Wennberg 44 11 9 20 -2 8 21 C Brayden Point 43 17 18 35 3 11 23 C Carter Verhaeghe 42 17 18 35 23 27 27 D Ryan McDonagh 39 4 7 11 11 12 26 C Scott Wilson - - - - - - 37 C Yanni Gourde 43 15 15 30 7 28 27 C Eetu Luostarinen 42 3 5 8 -10 12 44 D Jan Rutta 33 0 8 8 13 16 42 D Gustav Forsling 31 3 7 10 8 6 46 C Gemel Smith -

Lightning-Senators: Observations from Tampa Bay's 5-1

Lightning-Senators: Observations from Tampa Bay’s 5-1 win The Lightning have tied the NHL record for the fewest games it takes to get to 50 wins, dating back to the 1995-96 Detroit Red Wings. DIRK SHADD | Times Tampa Bay Lightning center Steven Stamkos (91) remains down after being hit awkwardly into boards behind the net during second period action at Amalie Arena in Tampa on Saturday, March 2, 2019. Stamkos into the locker room after the hit and did not return to the game or the bench during the second period. By Mari Faiello Published 6 hours ago TAMPA – The Lightning knew coming into Saturday’s matchup against the Senators that the team had something to prove. It was the same Ottawa Senators that had just fired the head coach Friday. The same Ottawa Senators coming into the contest with a meager 49 points and sitting last overall in the NHL standings. The same Ottawa Senators that had traded away a core part of their team throughout the season. The same Ottawa Senators that literally had nothing to lose, making them all the more dangerous. It’s why a 5-1 win, as expected as that might be when you’re the No. 1 team in the league, means so much at this point of the season. Here are some odds and ends from Tampa Bay’s win: Rough night for Steven Stamkos. Lightning fans held their breath when Stamkos hit ice after a hard slide by Brian Gibbons late in the second period. He kept a knelt position on the ice, leaning up against the boards as the play continued and got up without any assistance after about 10 seconds. -

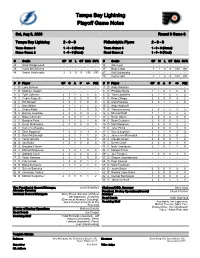

Tampa Bay Lightning Playoff Game Notes

Tampa Bay Lightning Playoff Game Notes Sat, Aug 8, 2020 Round 0 Game 6 Tampa Bay Lightning 2 - 0 - 0 Philadelphia Flyers 2 - 0 - 0 Team Game: 3 1 - 0 - 0 (Home) Team Game: 3 1 - 0 - 0 (Home) Home Game: 2 1 - 0 - 0 (Road) Road Game: 2 1 - 0 - 0 (Road) # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% 29 Scott Wedgewood - - - - - - 34 Alex Lyon - - - - - - 35 Curtis McElhinney - - - - - - 37 Brian Elliott 1 1 0 0 1.00 .941 88 Andrei Vasilevskiy 2 2 0 0 1.92 .933 67 Kirill Ustimenko - - - - - - 79 Carter Hart 1 1 0 0 1.00 .971 # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM 2 D Luke Schenn - - - - - - 3 D Andy Welinski - - - - - - 7 R Mathieu Joseph - - - - - - 5 D Philippe Myers 2 1 0 1 5 0 9 C Tyler Johnson 2 1 1 2 1 2 6 D Travis Sanheim 2 1 1 2 5 2 13 C Cedric Paquette 2 0 0 0 0 0 8 D Robert Hagg 2 0 0 0 -2 2 14 L Pat Maroon 2 0 1 1 0 0 9 D Ivan Provorov 2 0 1 1 2 0 17 L Alex Killorn 2 1 1 2 1 2 10 C Andy Andreoff - - - - - - 18 L Ondrej Palat 2 0 1 1 0 0 11 R Travis Konecny 2 0 2 2 3 2 19 C Barclay Goodrow 2 0 0 0 0 2 12 L Michael Raffl 1 1 1 2 2 2 20 C Blake Coleman 2 0 0 0 -1 7 13 C Kevin Hayes 2 0 4 4 4 0 21 C Brayden Point 2 1 1 2 1 6 14 C Sean Couturier 2 0 0 0 1 2 22 D Kevin Shattenkirk 2 0 0 0 0 0 15 D Matt Niskanen 2 0 0 0 2 2 23 C Carter Verhaeghe - - - - - - 18 C Tyler Pitlick 2 0 0 0 1 0 24 D Zach Bogosian 1 0 0 0 -1 0 21 C Scott Laughton 2 3 1 4 3 12 27 D Ryan McDonagh 2 0 1 1 1 0 25 L James van Riemsdyk 1 0 0 0 0 2 37 C Yanni Gourde 2 0 1 1 0 7 28 C Claude Giroux 2 0 0 0 1 0 44 D Jan Rutta 1 0 0 0 0 0 38 C Derek -

Template for up 2008 Proceedings

Assessing the offensive productivity of NHL players using in-game win probabilities Stephen Pettigrew Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA, 02138 Email: [email protected] Abstract Hockey journalists and statisticians currently lack many of the empirical tools available in other sports. In this paper I introduce a win probability metric for the NHL and use it to develop a new statistic, Added Goal Value, which evaluates player offensive productivity. The metric is the first of its kind to incorporate powerplay information and is the only NHL in-game win probability metric currently available. I show how win probabilities can enhance the narrative around an individual game and can also be used to evaluate playoff series win probabilities. I then introduce Added Goal Value which improves upon traditional offensive player statistics by accounting for game context. A player's AGV has a strong positive correlation between seasons, making it a useful statistic for predicting future offensive productivity. By accounting for the context in which goals are scored, AGV also allows for comparisons to be made between players who have identical goal- scoring rates. The work in this paper provides several advances in hockey analytics and also provides a framework for unifying current and future work on Corsi, Fenwick, and other NHL analytics. 1 Introduction Despite progress that has been made in recent years, NHL executives, writers, and fans lack many of the analytical and empirical tools that are available for analyzing baseball [1], basketball [2], football [3], and other sports [4]. This paper introduces two new analytical tools for the NHL. -

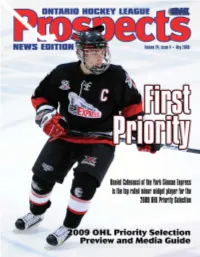

OHL Priority Selection Preview and Media Guide:OHL News.Qxd

OHL PRIORITY SELECTION OHL Priority Selection Process In 2001, the Ontario Hockey League Selected Players in the OHL with non-playoff teams selecting ahead Scouting Bureau with evaluations from conducted the annual Priority Selec- OHL Member Teams are permitted to of playoff teams. their team scouting staffs to make their tion process by way of the Internet for register a maximum of four 16 year old player selections. the first time in league history. players selected in the OHL Priority Teams are permitted to trade draft Selection. Those 16 year old players choices, other than their first round se- The OHL Central Scouting Bureau The new process allowed for eligible that are allowed to be signed are the lection, during the trading period from has been evaluating players since the players and their families, as well as fans first two 16 year old players selected Monday April 28 to Friday May 2, 1975-76 season. across the league to follow the process and a maximum addition of two 16 2008 at 3:00 p.m. in real time online. year old wild carded players in any OHL Central Scouting Staff round of the OHL Priority Selection. OHL Central Scouting Chief Scout - Robert Kitamura The 2008 OHL Priority Selection will The Central Scouting Bureau of the GTA - Tim Cherry once again be conducted online on All other 16-year-old players selected Ontario Hockey League is an informa- Central Ontario - Kyle Branch Saturday May 3, 2008 beginning at are eligible to be called up as an “affili- tion service and support organization Kingston and Area - John Finlay 9:00 a.m. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MAY 19, 2020 Mcdavid, MATTHEWS WIN

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MAY 19, 2020 McDAVID, MATTHEWS WIN ART ROSS, MAURICE “ROCKET” RICHARD TROPHIES NEW YORK (May 19, 2021) – The 2020-21 National Hockey League regular season concluded today with Edmonton Oilers center Connor McDavid capturing his third Art Ross Trophy as the League’s scoring champion and Toronto Maple Leafs center Auston Matthews claiming his first Maurice “Rocket” Richard Trophy as the NHL’s goal-scoring leader. McDavid registered a League-best 105 points (33-72—105 in 56 GP) – 21 more than the next-closest player (teammate Leon Draisaitl: 31-53—84 in 56 GP) – to earn his third career Art Ross Trophy, adding to back-to-back wins 2016-17 and 2017-18. He became the ninth player in NHL history to claim the award at least three times as well as the third to achieve the feat prior to his 25th birthday, following Wayne Gretzky (5x) and Gordie Howe (3x). McDavid’s 21-point gap over the runner-up was the largest by an NHL scoring champion since 1990-91, when Gretzky (41-122—163 in 78 GP w/ LAK) finished 32 points ahead of Brett Hull (86-45—131 in 78 GP w/ STL). McDavid, who also topped the League in assists (72), power-play assists (28) and power-play points (37), factored on 57.38 percent of Edmonton’s 183 total goals (excluding the shootout) – the highest single-season percentage in NHL history, ahead of Mario Lemieux in 1988-89 (57.35% w/ PIT). He also posted a League- leading 1.88 points per game – the most by any player since 1995-96, when Lemieux averaged 2.30 (69-92—161 in 70 GP w/ PIT). -

Season Like No Other Ends with Lightning

SEASON LIKE NO OTHER ENDS WITH LIGHTNING LIFTING STANLEY CUP Nearly a full year after the opening face-off of the 2019-20 campaign and more than six months after the League hit “pause” on the regular season, the Tampa Bay Lightning won Game 6 of the Stanley Cup Final to claim their second championship. * The clinching victory came 363 days after the puck dropped on the regular season, 201 days after the pause began and 65 days after players entered “Bubbles” in Edmonton and Toronto for a postseason unlike any other in League history. * The Lightning opened their 27th season with a victory against the intrastate rival Panthers on Oct. 3, 2019, and concluded it by hoisting the Cup to avenge one of the most monumental upsets in League history. After matching the single-season NHL record for wins in 2018-19, the Lightning were swept by the Blue Jackets in the First Round. * Tampa Bay became the third team in NHL history to win the Stanley Cup after being swept in a best-of-seven series during the opening round of the previous postseason, joining the 1967 Maple Leafs and 1961 Black Hawks. * The Lightning are the first franchise to join the League in the 1990s or later and win the Stanley Cup multiple times, though the trophy presentation looked quite different this time around. Former captain Dave Andreychuk accepted the team’s first Cup on June 7, 2004 after Game 7 against the Calgary Flames in front of a crowd of 22,717 at St. Pete Times Forum, while current captain Steven Stamkos accepted the trophy alongside the entire team at center ice at Rogers Place in Edmonton. -

Nhl Morning Skate – Jan. 13, 2021 2020-21 Nhl Season

NHL MORNING SKATE – JAN. 13, 2021 2020-21 NHL SEASON OPENS WITH FIVE-GAME SLATE After a season like no other, the NHL is set for another unique campaign in 2020-21 that will bring rivalries to the forefront of a truncated 56-game schedule with temporary realignment that will see only divisional play. With added significance in every game, the season begins today with NBCSN hosting a tripleheader and Sportsnet airing two contests from the NHL’s first-ever All-Canadian division. * #NHLStats Pack: Season Openers * #NHLStats Pack: Approaching Milestones in 2020-21 * 2020-21 NHL Season: Did You Know? * #NHLStats Pack: Divisional Notes for 2020-21 * #NHLStats Offseason Summary LIGHTNING TO RAISE BANNER, BEGIN STANLEY CUP DEFENSE For the second time in franchise history and first since 2005-06, the Lightning will open a campaign as defending Stanley Cup champions when they host the Blackhawks on a banner- raising night at AMALIE Arena. * The Lightning and Blackhawks will share a division for the second time after each competing in the Norris Division in 1992-93, Tampa Bay’s inaugural campaign. The Lightning defeated the Blackhawks in their first-ever game on Oct. 7, 1992, noteworthy on account of Chris Kontos scoring four goals in a 7-3 win. * These teams also met in the 2015 Stanley Cup Final, a six-game victory for Chicago. After claiming a title of its own last season, Tampa Bay enters 2020-21 looking to improve upon the record of defending champions in season openers, which stands at 58-25-16 all-time, including a 3-4-3 mark over the last 10 campaigns. -

Tampa Bay Lightning Game Notes

Tampa Bay Lightning Game Notes Thu, Dec 12, 2019 NHL Game #488 Tampa Bay Lightning 15 - 11 - 3 (33 pts) Boston Bruins 20 - 6 - 6 (46 pts) Team Game: 30 7 - 6 - 1 (Home) Team Game: 33 12 - 1 - 5 (Home) Home Game: 15 8 - 5 - 2 (Road) Road Game: 15 8 - 5 - 1 (Road) # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% 35 Curtis McElhinney 8 3 3 2 3.62 .898 40 Tuukka Rask 19 13 3 3 2.19 .927 88 Andrei Vasilevskiy 21 12 8 1 2.82 .910 41 Jaroslav Halak 13 7 3 3 2.28 .927 # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM 2 D Luke Schenn 13 1 0 1 -7 13 10 L Anders Bjork 24 4 4 8 2 0 7 R Mathieu Joseph 28 4 3 7 0 14 13 C Charlie Coyle 32 6 10 16 1 10 9 C Tyler Johnson 27 7 7 14 0 2 14 R Chris Wagner 31 3 4 7 -3 15 13 C Cedric Paquette 21 3 6 9 -2 20 18 R Brett Ritchie 18 2 2 4 -4 19 14 L Pat Maroon 27 5 6 11 1 31 20 C Joakim Nordstrom 21 3 1 4 0 4 17 L Alex Killorn 27 9 15 24 6 10 25 D Brandon Carlo 32 2 8 10 7 6 18 L Ondrej Palat 29 9 7 16 9 14 26 C Par Lindholm 20 1 0 1 2 4 21 C Brayden Point 26 10 11 21 4 5 27 D John Moore 3 0 1 1 -1 5 22 D Kevin Shattenkirk 29 5 17 22 12 16 33 D Zdeno Chara 32 5 7 12 18 27 23 C Carter Verhaeghe 19 1 3 4 -3 4 37 C Patrice Bergeron 23 9 16 25 10 12 27 D Ryan McDonagh 29 1 8 9 2 9 42 R David Backes 11 1 2 3 -1 16 37 C Yanni Gourde 29 6 9 15 2 21 43 C Danton Heinen 32 5 8 13 4 4 44 D Jan Rutta 12 0 3 3 -1 6 46 C David Krejci 26 6 15 21 13 6 55 D Braydon Coburn 17 1 0 1 2 4 47 D Torey Krug 27 4 16 20 3 12 67 C Mitchell Stephens 2 0 0 0 -2 0 48 D Matt Grzelcyk 32 2 7 9 0 12 71 C Anthony Cirelli 28 6 15 21