In Ter Cult Ural Conceptions of Psychological Maturity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Female Tanner Stages (Sexual Maturity Rating)

Strength of Recommendations Preventive Care Visits – 6 to 17 years Bold = Good Greig Health Record Update 2016 Italics = Fair Plain Text = consensus or Selected Guidelines and Resources – Page 3 inconclusive evidence The CRAFFT Screening Interview Begin: “I’m going to ask you a few questions that I ask all my patients. Please be honest. I will keep your Screening for Major Depressive Disorder -USPSTF answers confidential.” Age 12 years to 18 years 7 to 11 yrs No Yes Part A During the past 12 months did you: Screen (when systems in place for diagnosis, treatment and Insufficient 1. Drink any alcohol (more than a few sips)? □ □ follow-up) evidence 2. Smoked any marijuana or hashish? □ □ Risk factors- parental depression, co-morbid mental health or chronic medical 3. Used anything else to get high? (“anything else” includes illegal conditions, having experienced a major negative life event drugs, over the counter and prescription drugs and things that you sniff or “huff”) □ □ Tools-Patient Health Questionnaire for Adolescent(PHQ9-A) Tools For clinic use only: Did the patient answer “yes” to any questions in Part A? &Beck Depression Inventory-Primary Care version (BDI-PC) perform less No □ Yes □ well Ask CAR question only, then stop. Ask all 6 CRAFFT questions Treatment-Pharmacotherapy – fluoxetine (a SSRI) is Part B Have you ever ridden in a CAR driven by someone □ □ efficacious but SSRIs have a risk of suicidality – consider only (including yourself) who was ‘‘high’’ or had been using if clinical monitoring is possible. Psychotherapy alone or alcohol or drugs? combined with pharmacotherapy can be efficacious. -

Leaving Your Child Home Alone

FACTSHEET FOR FAMILIES December 2018 Leaving Your Child Home WHAT’S INSIDE Alone What to consider before leaving your child home All parents eventually face the decision to leave alone their child home alone for the first time. Whether they are just running to the store for a few Tips for parents minutes or working during after-school hours, Resources parents need to be sure their child has the skills and maturity to handle the situation safely. Being trusted to stay home alone can be a positive experience for a child who is mature and well prepared and can boost the child’s confidence and promote independence and responsibility. However, children face real risks when left unsupervised. Those risks, as well as a child’s comfort level and ability to deal with challenges, must be considered. This factsheet provides some tips to help parents and caregivers when making this important decision. Children’s Bureau/ACYF/ACF/HHS 800.394.3366 | Email: [email protected] | https://www.childwelfare.gov Leaving Your Child Home Alone https://www.childwelfare.gov What to Consider Before Leaving Your States do not provide any detail on what is considered Child Home Alone “adequate supervision.” In some States, leaving a child without supervision at an inappropriate age or in When deciding whether to leave a child home alone, inappropriate circumstances may be considered neglect you will want to consider your child’s physical, mental, after considering factors that may put the child at risk of developmental, and emotional well-being; his or her harm, such as the child’s age, mental ability, and physical willingness to stay home alone; and laws and policies in condition; the length of the parent’s absence; and the your State regarding this issue. -

The Level of Maturity That Constitutes Adulthood

The Review: A Journal of Undergraduate Student Research Volume 7 Article 8 2004 The Level of Maturity that Constitutes Adulthood Peter Stoller St. John Fisher College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/ur Part of the American Studies Commons How has open access to Fisher Digital Publications benefited ou?y Recommended Citation Stoller, Peter. "The Level of Maturity that Constitutes Adulthood." The Review: A Journal of Undergraduate Student Research 7 (2004): 29-35. Web. [date of access]. <https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/ur/vol7/iss1/8>. This document is posted at https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/ur/vol7/iss1/8 and is brought to you for free and open access by Fisher Digital Publications at St. John Fisher College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Level of Maturity that Constitutes Adulthood Abstract In lieu of an abstract, below is the article's first paragraph. The United States of America provides its citizens with many freedoms and privileges unique to other nations worldwide. At 15, you may start working with the proper legal working papers. The same freedom that allows you the right to earn that living also allows the government to take taxes out of your paycheck as a thank you for the privilege. This very same government acknowledges the fact that you are old enough a U.S. citizen for the government to remove taxes, federal and/or state, from your paycheck. yet you're stilJ not old enough to vote in our nation's elections until 18 years of age. -

Taking Account of Maturity: Assessment and Good Practice

Taking account of maturity: assessment and good practice European alternatives to custody workshop. By Amy Hall Equality Officer What we will look at ● Introduction to maturity ● What the evidence tell us ● Best practice for staff and managers ● The T2A guide Introduction to maturity Changes in Guidelines ● Since 2011, adult sentencing guidelines published by the Sentencing Council for England and Wales have stated that consideration should be given to ‘lack of maturity’ as a potential mitigating factor in sentencing decisions for adults. ● Furthermore, since early 2013, the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS), in its new Code of Conduct, has for the first time included maturity as a factor for consideration of culpability as part of its public interest test. What is meant by the concept of Maturity? ● Maturity is a core, developmental concept which addresses the processes through which a young person achieves the status of adulthood. ● These developmental processes include the interactions between physical, intellectual, neurological, emotional and social development. ● Although physical and intellectual development is usually completed during adolescence, for some people emotional and social maturation can continue into the early to mid-twenties. ● Young adults often differ from each other because of their variable maturity and these differences often show themselves in the ways in which individuals manage the multiple transitions which are associated with the journey to adulthood. The concept of maturity is self evidently not the same as biological age. Blowing out the candles on an 18th birthday cake does not magically transform anyone into a fully functioning and mature adult – even without the life disadvantages many young people in criminal justice have experienced (T2A, 2012:2) Why is maturity important to CJS staff? ● In England and Wales, the age of 18 has been the point for determining whether criminal justice agencies respond with either juvenile or adult law. -

Psychosocial Maturity and Desistance from Crime in a Sample of Serious Juvenile Offenders Laurence Steinberg, Elizabeth Cauffman, and Kathryn C

U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention March 2015 Robert L. Listenbee, Administrator Pathways to Desistance Psychosocial Maturity and Desistance How and why do many serious adolescent offenders stop offending From Crime in a Sample of Serious while others continue to commit crimes? This series of bulletins presents findings Juvenile Offenders from the Pathways to Desistance study, a multidisciplinary investigation that Laurence Steinberg, Elizabeth Cauffman, and Kathryn C. Monahan attempts to answer this question. Investigators interviewed 1,354 young offenders from Philadelphia and Phoenix for 7 years after their Highlights convictions to learn what factors (e.g., individual maturation, life changes, and The Pathways to Desistance study followed more than 1,300 serious juvenile offenders involvement with the criminal justice for 7 years after their conviction. In this bulletin, the authors present key findings on system) lead youth who have committed the link between psychosocial maturity and desistance from crime in the males in the serious offenses to persist in or desist Pathways sample as they transition from midadolescence to early adulthood (ages from offending. 14–25): As a result of these interviews and a • Recent research indicates that youth experience protracted maturation, into review of official records, researchers their midtwenties, of brain systems responsible for self-regulation. This has have collected the most comprehensive stimulated interest in -

The Montana Adolescent Maturity Assessment-Parent Version (MAMA-P): a Rating Scale for Immaturity

A RATING SCALE FOR IMMATURITY The Montana Adolescent Maturity Assessment-Parent Version (MAMA-P): A Rating Scale for Immaturity Nicholas N. Hong, Ph.D. Montana Academy John A. McKinnon, M.D. Montana Academy John L. Santa, Ph.D. Montana Academy Melissa A. Napier, M.S. Northwest Montana Head Start Introduction Several years ago our clinical experience with troubled teenagers (i.e., adolescents brought for treatment to a private therapeutic high school located on a remote ranch in Montana by parents from suburban-urban hubs in 30 states) suggested these individuals shared a number of common clinical denominators. This occurred despite a long list of symptoms, signs, misbehaviors, and failures well-described in their histories, including well over 50 cumulative Axis-I DSM-IV diagnoses offered as explanations by hundreds of clinicians during prior failed attempts at outpatient treatment. These students demonstrated a panoply of symptoms, misbehaviors, and spectrum of dysfunction. Most had endured various dysphoric affects and anxieties for months, albeit none were obviously psychotic. Few had ever been arrested, none adjudicated, but many had been dishonest and sneaky. And most had disobeyed home or school rules and civic laws with impunity and without apparent remorse. Many reported distracting preoccupations (e.g., eating disturbances, serial intoxications, compulsive video-game use, florid promiscuity). Some had repeatedly injured themselves (i.e., a few had made suicidal gestures, and a very few had survived serious attempts). They had already failed most of the normative tasks of a modern adolescence at home, at school, and among age-peers socially. Invariably psychiatric outpatient treatments attempted by well-trained clinicians across the nation had failed, or outpatient treatment had become untenable when these young people could no longer safely live at home. -

Chapter 3: Overview of Developmental Theories

3 ❖ Overview of Developmental Theories Looking at Humans Over Time erhaps the most widely used conceptual approaches to describing and explaining P human activity, appearance, and experience are developmental. From word soup, we ladle the following synonyms for the term development: expansion, elaboration, growth, evolution, unfolding, opening, maturing, maturation, maturity, ripeness (Dictionary.com, n.d.). Drawing 3.1 Developmental Theories Word Soup 35 36 ❖ SECTION II THEORIES THAT DESCRIBE AND EXPLAIN Inherent in each of these words is movement or growth on a hierarchy from diminutive to grand, from immature to mature, and so forth. Reflecting positive movement, developmental theories have typically been referred to as stage, phase, life course theories, and, more recently, developmental science (Damon & Lerner, 2006). Initial theories of human development were concerned with how individuals unfold in an orderly and sequential fashion. However, over the past several decades, human development has expanded beyond looking at the passage of the individual through time to positioning human function and capability within comparative hierarchical frameworks. We discuss all of these approaches within the genre of developmental theories, noting that they have different scopes and foci, but contain commonalities. What unites all of them is the role of “development” depicted as degree of maturation or directional movement as descriptive and explanatory of humans, their interac- tions, and their contexts. Some developmental theories posit specific stages through which individual humans or entities pass and must negotiate, while others see chron- ological maturation as a fluid process without discrete identifiable boundaries that delineate the boundaries of entrance and exit from one state into the next. -

Empowerment-Based Positive Youth Development: a New Understanding of Healthy Development for African American Youth

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by IUPUIScholarWorks Empowerment-Based Positive Youth Development: A New Understanding of Healthy Development for African American Youth Raphael Travis Jr.1 Tamara G. J. Leech2 1. Texas State University – San Marcos 2. Indiana University – Purdue University, Indianapolis The authors wish to thank the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation New Connections Program for the generous Publication Support Grant that assisted in the preparation of this manuscript. Abstract A shift occurred in research about adolescents in the general population. Research is moving away from deficits toward a resilience paradigm and understanding trajectories of positive youth development. This shift has been less consistent in research and practice with African American youth. A gap also exists in understanding whether individual youth development dimensions generate potential in other dimensions. This study presents an empowerment-based positive youth development model. It builds upon existing research to present a new vision of healthy development for African American youth that is strengths-based, developmental, culture-bound, and action-oriented. It emphasizes the relationship between person and environment, the reinforcing nature of developmental assets, and the necessity of a sense of community and community engagement for youth. This is the author's manuscript of the article published in final edited form as: Travis, R., & Leech, T. G. J. (2014). Empowerment-Based Positive Youth Development: A New -

Findings from the 4-H Study of Positive Youth Development

The Positive Development of Youth: Comprehensive Findings from the 4-H Study of Positive Youth Development Richard M. Lerner, Jacqueline V. Lerner, and Colleagues FOREWORD The fi rst-of-its-kind research defi ned and measured positive youth development. The result is a model that is driving new thinking and approaches to youth development around the world. For more than a decade, preeminent youth development scholars, Drs. Richard M. Lerner and Jacqueline V. Lerner, and the team at the Institute for Applied Research in Youth Development at Tuft s University, Medford, MA, partnered with faculty at America’s land-grant universities to conduct this groundbreaking research. The fi nal report, The Positive Development of Youth: Comprehensive Findings from the 4-H Study of Positive Youth Development, reviews the multi-year research fi ndings. RESEARCH SHOWS 4-H YOUTH EXCEL BEYOND THEIR PEERS The longitudinal study discovered that the structured out-of-school time learning, leadership experiences, and adult mentoring that young people receive through their participation in 4-H plays a vital role in helping them achieve success. Compared to their peers, the fi ndings show that youth involved in 4-H programs excel in several 4-H’ers Excel areas: s )FSTJO(SBEFTBSFOFBSMZ Contribution/Civic Engagement UJNFTNPSFMJLFMZUPNBLF s 4-H’ers are nearly 4 times more likely to DPOUSJCVUJPOTUPUIFJSDPNNVOJUJFT make contributions to their communities (Grades 7-12) s )FSTJO(SBEFTBSFBCPVUUJNFT NPSFMJLFMZUPCFDJWJDBMMZBDUJWF s 4-H’ers are about 2 times more likely to be -

Evolutionary Developmental Psychology

Psicothema 2010. Vol. 22, nº 1, pp. 22-27 ISSN 0214 - 9915 CODEN PSOTEG www.psicothema.com Copyright © 2010 Psicothema Evolutionary developmental psychology Ashley C. King and David F. Bjorklund* University of Arizona and * Florida Atlantic University The field of evolutionary developmental psychology can potentially broaden the horizons of mainstream evolutionary psychology by combining the principles of Darwinian evolution by natural selection with the study of human development, focusing on the epigenetic effects that occur between humans and their environment in a way that attempts to explain how evolved psychological mechanisms become expressed in the phenotypes of adults. An evolutionary developmental perspective includes an appreciation of comparative research and we, among others, argue that contrasting the cognition of humans with that of nonhuman primates can provide a framework with which to understand how human cognitive abilities and intelligence evolved. Furthermore, we argue that several «immature» aspects of childhood (e.g., play and immature cognition) serve both as deferred adaptations as well as imparting immediate benefits. Intense selection pressure was surely exerted on childhood over human evolutionary history and, as a result, neglecting to consider the early developmental period of children when studying their later adulthood produces an incomplete picture of the evolved adaptations expressed through human behavior and cognition. Psicología evolucionista del desarrollo. El campo de la psicología evolucionista del desarrollo puede am- pliar potencialmente los horizontes de la psicología evolucionista, combinando los principios darwinistas de la evolución por selección natural con el estudio del desarrollo humano, centrándose en los efectos epi- genéticos entre los seres humanos y su entorno, de manera que explique cómo los mecanismos psicológi- cos evolucionados se acaban expresando en el fenotipo de los sujetos adultos. -

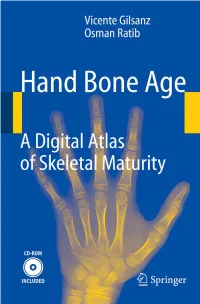

Hand Bone Age: a Digital Atlas of Skeletal Maturity

V. Gilsanz/O. Ratib · Hand Bone Age Vicente Gilsanz · Osman Ratib Hand Bone Age A Digital Atlas of Skeletal Maturity With 88 Figures Vicente Gilsanz, M.D., Ph.D. Department of Radiology Childrens Hospital Los Angeles 4650 Sunset Blvd., MS#81 Los Angeles, CA 90027 Osman Ratib, M.D., Ph.D. Department of Radiology David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA 100 Medical Plaza Los Angeles, CA 90095 This eBook does not include ancillary media that was packaged with the printed version of the book. ISBN 3-540-20951-4 Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg New York Library of Congress Control Number: 2004114078 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilm or in any other way, and storage in data banks. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the German Copyright Law of September 9, 1965, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer-Verlag. Violations are liable to prosecution under the German Copyright Law. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg New York Springer is a part of Springer Science+Business Media http://www.springeronline.com A Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2005 Printed in Germany The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from therelevantprotectivelawsandregulationsandthereforefreeforgeneraluse. Product liability: The publishers cannot guarantee the accuracy of any information about the application of operative techniques and medications contained in this book. -

Formation of Personality Psychological Maturity and Adulthood Crises Victoria R

Psychology in Russia: State of the Art Russian Lomonosov Psychological Moscow State Volume 8, Issue 2, 2015 Society University Formation of personality psychological maturity and adulthood crises Victoria R. Manukyan, Larisa A. Golovey*, Olga Yu. Strizhitskaya Saint Petersburg State University, Saint Petersburg, Russia *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Based on theoretical analysis, in the present paper, we defined the structure of the charac- teristics of personality psychological maturity, which is considered an adult development criterion. The objective of this paper was to identify the mechanisms that contribute to the formation of psychological maturity in adulthood development. We first assumed that one of the possible mechanisms is the normative crisis of development. In turn, previously formed psychological maturity traits can relieve the experiences associated with this normative crisis. The aim of the present study was to analyze the formation of psychological maturity during periods of emerging and middle adulthood, with a specific focus on normative crisis experi- ences. The study design included cross-sectional and longitudinal methods. The participants included 309 adults. The emerging adulthood group ranged in age from 18 to 25 years, and the participants in the middle adulthood group were between 38 and 45 years of age. To study cri- sis events and experiences, we used three author-designed questionnaires. A self-actualization test by E. Shostrom (SAT), the Big Five personality test by Costa and MacCrae, a value and availability ratio in various vital spheres technique by E.B. Fantalova, a purpose-in-life test by D.A. Leontiev, and a coping test by Lazarus were used to define the personality characteristics used to overcome difficult life situations.