Vaping Linked with Severe Lung Illnesses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dry Vitamin E- Acetate 50% DC/GFP

Dry Vitamin E-Acetate 50% DC Chemical names of active ingredient DL--tocopheryl acetate, DL-alpha-tocopherol acetate, all-rac-alpha- tocopherol acetic acid ester, racemic 5,7,8-trim- ethyltocol acetate CAS-No. 52225-20-4 C31H52O3 Molar mass 472.8 g/mol EINECS-No. 231-710-0 Monographs PRD-No. The product complies with the current “-tocopheryl 30041051 acetate concentrate (powder form)” Ph. Eur. and “Vitamin E preparation” USP monographs. Article Regulations 50051053 25 kg bag in box The product meets the regulatory requirements for a vitamin E source in most countries. How- Country of origin ever, regulations on the ingredients used in the Denmark respective countries and for the intended use have to be observed. Units 1 International Unit (IU) = 1 mg vitamin E-acetate Bulk density Approx. 0.5 g/ml Description Dry, almost white, virtually odorless, free-flowing Stability powder, consisting of spherical particles. The stability of Dry Vitamin E-Acetate 50% DC is excellent even in the presence of minerals. Composition Stored in its original packaging at room tem- Ingredients in descending order of weight: perature (max. 25 °C), the product is stable for DL-alpha-tocopheryl acetate, corn starch, gelatin, at least 36 months. sucrose, sodium aluminum silicate. Storage/Handling Solubility The product should be stored in the original Dispersible in warm water (35 – 40 °C), to form a packaging in a dry place at room temperature milky emulsion. Insoluble particles may be visible. (max. 25 °C). Specification Assay min. 50% DL--tocopheryl acetate (= 500 former IU of vitamin E = 336 -TE per gram) For further information see separate document: “Standard Specification” (not for regulatory purposes) available via BASF’s WorldAccount: https://worldaccount.basf.com (registered access). -

United States Patent 0 Patented Nov

2,723,278 United States Patent 0 Patented Nov. 8, 1955 1 2 was cooled to room temperature and ?ltered, then washed 2,723,278 twice with water, and the solvent was removed by dis PREPARATION OF ALPHA-TOCOPHEROL tillation under vacuum. The residue, a-dl-tocopherol, was Joseph Donald Surmatis, Pompton Plains, and Joseph a light-colored, yellow syrup. Weber, Paterson, N. J ., assignors to Holfmann-La Roche To this residual syrup was added 800 cc. of acetic Inc., Roche Park, N. J., a corporation of New Jersey anhydride, and the reaction mixture was re?uxed for 3 No Drawing. Application January 25, 1954, hours. The excess acetic anhydride was removed under Serial No. 406,079 a vacuum of about 20 mm. and the product was then distilled under a high vacuum to produce an almost water 4 Claims. (Cl. 260—345.5) 10 white syrup of dl-a-tocopheryl acetate. This invention relates to an improved process for Example 2 making e-tocopherol. More particularly, it relates to such a process wherein phytyl chloride is condensed with 5.0 kg. of isophytol (about 95% pure) was stirred trimethylhydroquinone in the presence of a boron tri with 15 liters of technical grade 37% aqueous hydro ?uoride catalyst. In the practice of the invention on a 15 chloric acid at room temperature for about 2 hours. The large scale, the process thereof has made it possible to pro acid layer was separated, extracted with petroleum ether duce in excellent yield a vitamin E product characterized and the extract added to the oil layer. -

Degradation of Tocopherol and Tocopheryl Acetate by Ruminal Contents in Vitro

DEGRADATION OF TOCOPHEROL AND TOCOPHERYL ACETATE BY RUMINAL CONTENTS IN VITRO 1999 Animal Science Research Report Pages 119-125 Authors: Story in Brief H. Han and F. N. Ruminal fluid, from ruminally cannulated beef steers (300kg) fed a Owens concentrate or a high roughage diet, was used to measure disappearance of α -tocopherol and hydrolysis of α -tocopheryl acetate to α -tocopherol in vitro. Undiluted ruminal fluid was used in Exp. 1, while buffer was added in Exp. 2. Degradation of α -tocopherol or conversion of α -tocopheryl acetate into α -tocopherol was estimated after 12 and 24 h incubation of each α - tocopherol in ruminal fluid. Following 24 h incubation in ruminal fluid, the α -tocopherol concentration in ruminal fluid was not changed in either Exp. 1 or Exp. 2 by α -tocopherol or tocopheryl acetate. These results suggest that α -tocopherol is not destroyed in the rumen and that α -tocopheryl acetate was not extensively changed into α -tocopherol by ruminal microbes. Key Words: In vitro, Rumen, Vitamin E, Destruction Introduction Most studies of bioavailability of vitamin E have monitored responses in the blood or tissue α -tocopherol concentration. Such studies have been reported for ruminants (Njeru et al., 1995; Hidiroglou et al., 1992), swine (Chung et al., 1992) and horses (Siciliano et al., 1997). Based on those studies, d-α -tocopherol has a higher bioavailability than other forms of vitamin E. Because the acetate form is less susceptible to oxidative destruction, α -tocopheryl acetate is used widely in the feed industry as a source of vitamin E. -

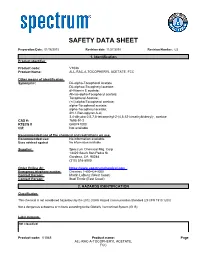

Safety Data Sheet

SAFETY DATA SHEET Preparation Date: 01/16/2015 Revision date 11/27/2018 Revision Number: G2 1. Identification Product identifier Product code: V1048 Product Name: ALL-RAC-A-TOCOPHERYL ACETATE, FCC Other means of identification Synonyms: DL-alpha-Tocopherol Acetate DL-alphaa-Tocopheryl acetate; dl-Vitamin E acetate; All-rac-alpha-Tocopheryl acetate; Tocopherol Acetate; (+/-)-alpha-Tocopherol acetate; alpha-Tocopherol acetate; alpha-Tocopheryl acetate; 2H-1-Benzopyran-6-ol, 3,4-dihydro-2,5,7,8-tetramethyl-2-(4,8,12-trimethyltridecyl)-, acetate CAS #: 7695-91-2 RTECS # GA8747000 CI#: Not available Recommended use of the chemical and restrictions on use Recommended use: No information available. Uses advised against No information available Supplier: Spectrum Chemical Mfg. Corp 14422 South San Pedro St. Gardena, CA 90248 (310) 516-8000 Order Online At: https://www.spectrumchemical.com Emergency telephone number Chemtrec 1-800-424-9300 Contact Person: Martin LaBenz (West Coast) Contact Person: Ibad Tirmiz (East Coast) 2. HAZARDS IDENTIFICATION Classification This chemical is not considered hazardous by the 2012 OSHA Hazard Communication Standard (29 CFR 1910.1200) Not a dangerous substance or mixture according to the Globally Harmonized System (GHS) Label elements Not classified Product code: V1048 Product name: Page ALL-RAC-A-TOCOPHERYL ACETATE, FCC Hazards not otherwise classified (HNOC) Not Applicable Other hazards Not available 3. COMPOSITION/INFORMATION ON INGREDIENTS Formula: CAS No Weight-% Vitamin E Acetate 7695-91-2 100 4. FIRST AID MEASURES First aid measures General Advice: National Capital Poison Center in the United States can provide assistance if you have a poison emergency and need to talk to a poison specialist. -

Analysis of Cannabinoid-Containing Fluids in Illicit Vaping Cartridges Recovered from Pulmonary Injury Patients: Identification of Vitamin E Acetate As a Major Diluent

toxics Article Analysis of Cannabinoid-Containing Fluids in Illicit Vaping Cartridges Recovered from Pulmonary Injury Patients: Identification of Vitamin E Acetate as a Major Diluent Bryan Duffy 1, Lingyun Li 1, Shijun Lu 1,2, Lorie Durocher 1, Mark Dittmar 1, Emily Delaney-Baldwin 1, Deepika Panawennage 1, David LeMaster 3, Kristen Navarette 4,5 and David Spink 1,2,* 1 Laboratory of Organic Analytical Chemistry, Wadsworth Center, New York State Department of Health, Albany, NY 12201, USA; bryan.duff[email protected] (B.D.); [email protected] (L.L.); [email protected] (S.L.); [email protected] (L.D.); [email protected] (M.D.); [email protected] (E.D.-B.); [email protected] (D.P.) 2 Department of Environmental Health Sciences, School of Public Health, University at Albany, State University of New York, Rensselaer, NY 12144, USA 3 Laboratory of Molecular Diagnostics, Wadsworth Center, New York State Department of Health, Albany, NY 12201, USA; [email protected] 4 Center for Environmental Health, New York State Department of Health, Albany, NY 12201, USA; [email protected] 5 Albany Medical Center, Department of Pediatrics, Albany, NY 12208, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-518-486-2530 Received: 3 December 2019; Accepted: 17 December 2019; Published: 24 January 2020 Abstract: Beginning in June of 2019, there was a marked increase in reported cases of serious pulmonary injury associated with vaping. The condition, referred to as e-cigarette or vaping product use-associated lung injury (EVALI), does not appear to involve an infectious agent; rather, a chemical adulterant or contaminant in vaping fluids is suspected. -

Vitamin E: a Review of Its Application and Methods of Detection When Combined with Implant Biomaterials

materials Review Vitamin E: A Review of Its Application and Methods of Detection When Combined with Implant Biomaterials Francesca Gamna * and Silvia Spriano Department of Applied Science and Technology, Politecnico di Torino, 10129 Torino, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Vitamin E is a common compound used for tocopherols and tocotrienols (α, β, γ, δ); it is the component of many natural products of both plant and animal origin. Thanks to its powerful antioxidant capacity, vitamin E has been very successful in hip and knee arthroplasty, used to confer resistance to oxidation to irradiated UHMWPE. The positive results of these studies have made vitamin E an important object of research in the biomedical field, highlighting other important properties, such as anti-bacterial, -inflammatory, and -cancer activities. In fact, there is an extensive literature dealing with vitamin E in different kinds of material processing, drug delivery, and development of surface coatings. Vitamin E is widely discussed in the literature, and it is possible to find many reviews that discuss the biological role of vitamin E and its applications in food packaging and cosmetics. However, to date, there is not a review that discusses the biomedical applications of vitamin E and that points to the methods used to detect it within a solid. This review specifically aims to compile research about new biomedical applications of vitamin E carried out in the last 20 years, with the intention of providing an overview of the methodologies used to combine it with implantable biomaterials, as well as to detect and characterize it within these materials. -

Research Progress in Enzymatic Synthesis of Vitamin E Ester Derivatives

catalysts Review Research Progress in Enzymatic Synthesis of Vitamin E Ester Derivatives Zhiqiang Zou 1, Lingmei Dai 1, Dehua Liu 1,2 and Wei Du 1,2,* 1 Key Laboratory for Industrial Biocatalysis, Department of Chemical Engineering, Tsinghua University, Ministry of Education, Beijing 100084, China; [email protected] (Z.Z.); [email protected] (L.D.); [email protected] (D.L.) 2 Tsinghua Innovation Center in Dongguan, Dongguan 523808, China * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Vitamin E is easily oxidized by light, air, oxidizing agents and heat, limiting its application in many ways. Compared to vitamin E, vitamin E ester derivatives exhibit improved stability and a stronger antioxidant capacity, and even gain new biological functions. In recent years, enzymatic synthesis of vitamin E ester derivatives has received increasing attention due to its environmental friendliness, high catalytic efficiency, and inherent selectivity. This paper reviews the related progress of lipase-mediated preparation of vitamin E ester derivatives. The function of different vitamin E ester derivatives, and the main factors influencing the enzymatic acylation process, including enzyme species, acyl donor and acceptor, reaction media and water activity, are summarized in this paper. Finally, the perspective of lipase-catalyzed synthesis of vitamin E ester derivatives is also discussed. Keywords: antioxidants; derivatives; lipase; vitamin E; vitamin E ester Citation: Zou, Z.; Dai, L.; Liu, D.; Du, W. Research Progress in Enzymatic Synthesis of Vitamin E Ester Derivatives. Catalysts 2021, 11, 739. 1. Introduction https://doi.org/10.3390/ Vitamin E (VE) is a group of eight liposoluble compounds, including four tocopherols catal11060739 and four tocotrienols. -

Development of Novel Formulations to Enhance in Vivo Transdermal Permeation of Tocopherol

Acta Pharm. 64 (2014) 299–309 Original research paper DOI: 10.2478/acph-2014-0021 Development of novel formulations to enhance in vivo transdermal permeation of tocopherol ALY H. NADA* Tocopherol represents a big challenge for transdermal per- ABDELAZIM A. ZAGHLOUL meation owing to its extreme hydrophobicity and large mo- MOHSEN M. HEDAYA IBRAHIM S. KHATTABa le cular mass. The aim of the present study was to develop alpha-tocopherol (T) topical formulations and evaluate Department of Pharmaceutics their ex vivo and in vivo permeation. Franz diffusion cells Faculty of Pharmacy were used for ex vivo permeation, and neonatal rats were Kuwait University, Kuwait used for in vivo permeation. Seven gel formulations and 21 liquid formulations were investigated for physical stability, a Current address: viscosity and permeation of T. Analysis of T was performed Kuwaiti Saudi Pharmaceutical by a validated HPLC method using a UV detector. The ex Company (KSPICO), Kuwait vivo permeation from gel and emulsion formulations was very poor (0.001–0.015 %). Highest permeation was ob- served from monophasic liquid formulations containing dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), tocopheryl polyethylene gly- cols (TPGs), propylene glycol, ethanol and 9.5 % T. The in vivo results demonstrated higher retention in the epidermis compared to subcutaneous tissues, 1377 and 1.13 µg g–1, re- spectively. Increasing T concentration from 4.8 to 9.5 % did not increase the amount permeated or % of T retained. It was concluded that simple solutions of T in the presence of DMSO and TPGs were more promising systems for effec- tive transdermal permeation compared to gel, emulsion or oleaginous systems. -

Pulmonary Toxicity and Inflammatory Response of E-Cigarettes Containing

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.14.151381; this version posted June 15, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Research article 2 Pulmonary toxicity and inflammatory response of 3 e-cigarettes containing medium-chain triglyceride oil 4 and vitamin E acetate: Implications in the 5 pathogenesis of EVALI but independent of 6 SARS-COV-2 COVID-19 related proteins 7 8 Thivanka Muthumalage1, Joseph H. Lucas1, Qixin Wang1, Thomas 9 Lamb1, Matthew D. McGraw2, and Irfan Rahman1,* 10 1 Department of Environmental Medicine, University of Rochester Medical Center, School of Medicine & 11 Dentistry, Rochester, NY, USA. 12 2 Division of Pediatric Pulmonology, University of Rochester Medical Center, School of Medicine & 13 Dentistry, Rochester, NY, USA. 14 * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: 1-(585)-275-6911 15 Abstract: Recently, there has been an outbreak associated with the use of e-cigarette or vaping 16 products, associated lung injury (EVALI). The primary components of vaping products, vitamin E 17 acetate (VEA) and medium-chain triglycerides (MCT) may be responsible for acute lung toxicity. 18 Currently, little information is available on the physiological and biological effects of exposure to 19 these products. We hypothesized that these e-cig cartridges and their constituents (VEA and MCT) 20 induce pulmonary toxicity, mediated by oxidative damage and inflammatory responses, leading to 21 acute lung injury. We studied the potential mechanisms of cartridge aerosol induced 22 inflammatory response by evaluating the generation of reactive oxygen species by MCT, VEA, and 23 cartridges, and their effects on the inflammatory state of pulmonary epithelium and immune cells 24 both in vitro and in vivo. -

Spectrofluorometric and High-Performance Liquid

ARTICLE IN PRESS JOURNAL OF FOOD COMPOSITION AND ANALYSIS Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 20 (2007) 57–62 www.elsevier.com/locate/jfca Short Communication Spectrofluorometric and high-performance liquid chromatographic determination of all-rac-a-tocopheryl acetate in virgin olive oil Il Kyu Choa, Jamil Rimab, Chiou Ling Changc, Qing X. Lia,Ã aDepartment of Molecular Biosciences and Bioengineering, University of Hawaii at Manoa, 1955 East-West Road, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA bLaboratory of Molecular Chemistry, Faculty of Science II, The Lebanese University, Fanar, P.O. Box 26110217, Lebanon cUS Pacific Basin Agricultural Research Center, 2727 Woodlawn Drive, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA Received 4 October 2005; received in revised form 21 June 2006; accepted 28 June 2006 Abstract A high-performance liquid chromatographic (HPLC) method was developed for the analysis of all-rac-a-tocopheryl acetate in olive oil. After extraction of all-rac-a-tocopheryl acetate from olive oil into hexane/ethyl acetate (4:1, v/v), it was measured with HPLC-diode array detection and regular external standard calibration and confirmed with liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry. Spectro- fluorometric and standard addition methods were also used to quantify all-rac-a-tocopheryl acetate in olive oil. A standard addition method is based on fortification of known concentrations of all-rac-a-tocopheryl acetate in a sample. The concentrations (30.47 1.2 mg/mL) of all-rac-a-tocopheryl acetate determined with the HPLC method were comparable with those (32.671.1 mg/mL) with the spectrofluorometric method. Standards were checked for linearity giving correlation coefficients of higher than 0.999 in a concentration range from 0.5 to 20 mg/mL. -

RISK PROFILE of Vitamin E

RISK PROFILE Vitamin E Date of reporting 10.12.201 2 Content of document 1. Identification of substance ..................................................................... p. 1 2. Uses and origin .................................................................................. p. 2 3. Regulation .............................................................................................. p. 4 4. Relevant toxicity studies ..................................................................... p. 5 5. Exposure estimates and critical NOAEL/NOEL ............................................ p. 9 6. Other sources of exposure than cosmetic products ............................... p. 10 7. Assessment .............................................................................................. p. 12 8. Conclusion .............................................................................................. p. 13 9. References .............................................................................................. p. 14 10. Annexes .............................................................................................. p. 18 1. Identification of substance Chemical name 3,4-Dihydro-2,5,7,8-tetramethyl-2-(4,8,12-trimethyltridecyl)-2H-benzopyran- (IUPAC): 6-ol; Alpha-tocopherol; Vitamin E INCI Tocopherol (Common name: Vitamin E) Tocopheryl acetate Tocopheryl linoleate Tocopheryl succinate Synonyms Tocopherols are a class of naturally occurring chemical compounds related to Vitamin E CAS No. Alpha-Tocopherol: 59-02-9; 10191-41-0 Alpha-Tocopheryl -

01 Excipients Prelims 1..9

Alpha Tocopherol 31 20 General References 21 Authors A Allen LV. Oleaginous vehicles. Int J Pharm Compound 2000; 4(6): 470–472. SA Shah, D Thassu. Anonymous. Iodine 2% in oil injection. Int J Pharm Compound 2001; 5(2): 131. Brown JH et al. Oxidative stability of botanical emollients. Cosmet Toilet 1997; 112(Jul): 87–9092, 94, 96–98. 22 Date of Revision Shaath NA, Benveniste B. Natural oil of bitter almond. Perfum Flavor 1991; 16(Nov–Dec): 17, 19–24. 12 February 2009. Alpha Tocopherol 1 Nonproprietary Names 7 Applications in Pharmaceutical Formulation or BP: RRR-Alpha-Tocopherol Technology JP: Tocopherol Alpha tocopherol is primarily recognized as a source of vitamin E, PhEur: RRR-a-Tocopherol and the commercially available materials and specifications reflect this purpose. While alpha tocopherol also exhibits antioxidant USP: Vitamin E properties, the beta, delta, and gamma tocopherols are considered See also Sections 3, 9, and 17. to be more effective as antioxidants. Alpha-tocopherol is a highly lipophilic compound, and is an 2 Synonyms excellent solvent for many poorly soluble drugs.(1–4) Of widespread Copherol F1300;(Æ)-3,4-dihydro-2,5,7,8-tetramethyl-2-(4,8,12- regulatory acceptability, tocopherols are of value in oil- or fat-based trimethyltridecyl)-2H-1-benzopyran-6-ol; E307; RRR-a-tocopher- pharmaceutical products and are normally used in the concentra- olum; synthetic alpha tocopherol; all-rac-a-tocopherol; dl-a-toco- tion range 0.001–0.05% v/v. There is frequently an optimum pherol; 5,7,8-trimethyltocol. concentration; thus the autoxidation of linoleic acid and methyl linolenate is reduced at low concentrations of alpha tocopherol, and 3 Chemical Name and CAS Registry Number is accelerated by higher concentrations.