THE PLANNING of COMMEMORATIVE WORKS in CANBERRA on Death and Sublation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CAN YOU SAVE the NATIONAL CAPITAL? Role Play

Role Play CAN YOU SAVE THE NATIONAL CAPITAL? Role Play CAN YOU SAVE THE NATIONAL CAPITAL? STEP 1 Questions for you to discuss 1 What is this building? 2 Who are the people in the room inside the building? 3 What are they doing? 4 These people are our representatives. What does that mean? 5 Why do we have laws that apply to all people equally in Australia? STEP 2 Imagine you have been asked to write a message that will be put at the front of this building. Here is the start of the message. How will you finish it? “This place is important to all Australians because . “ If you cannot answer any of these questions look at the clues. But do not look at them unless you really have to. When you have worked out the message you need to present that message to the rest of the class. But we do not want you to TELL them what your message is, we want you to SHOW them through a role play! STEP 3 Work out your role play to get your message across to the rest of your class You have created your message. It will be something like: “This place is important to all Australians because it is where the representatives we elect to Parliament meet to pass laws for all Australians.” How can you get this message across in your role play? You need to: 1 Show the rest of your class that this place is Parliament House 2 Show the rest of the class that people are elected to go there as representatives of Australians 3 Show the rest of your class that they make laws there for all Australians. -

Inquiry Into Canberra's National Institutions Submission 54

National Archives of NA Australia Concept Design Report 27 July 2018 J PW JOHNSON PILTON WALKER Introduction Contents New Permanent Headquarters Introduction 2 Effective records and archives JPW was engaged in May 2018 to develop New Permanent Headquarters management is an essential a concept design and site masterplan for a new permanent headquarters building for the National Cultural Institution precondition for good governance, National Archives of Australia. the rule of law, administrative Vision 6 transparency, the preservation of The National Archives is the only national Stewardship of Records collecting institution without a permanent and mankind's collective memory, and purpose built national headquarters. The Information Society access to information by citizens. The idea for a National Archives can be traced Parliamentary Zone Site 12 International Council on Archives back to the original Burley Griffin design National Capital Plan for Canberra more than a century ago. The foundation stone for a National Archives was Humanities & Science Campus laid by Edward, Prince of Wales in Canberra Square in 1920 however no building was constructed Site Masterplan after the ceremony. NAA Headquarters Building 16 In 1983 Ken Woolley of Anchor Mortlock Concept Design Woolley was appointed to provide preliminary sketch plans for the construction of the Functional Area Schedule Australian Archives Headquarters building in the Parliamentary Zone. In the context of the Precedents 30 Stock Market Crash of 1987 and pressures Archives Buildings -

Joint Standing Committee Inquiry Into the Immigration Bridge Australia Proposal

Joint Standing Committee Inquiry into the Immigration Bridge Australia Proposal National Trust of Australia (ACT) ‐ Response Introduction The ACT National Trust (‘the Trust’) appreciates the opportunity to present its views to the Joint Committee on the proposed footbridge to be erected over Lake Burley Griffin from Kurrajong Point west of the southern approach to Commonwealth Avenue Bridge to Hospital Point. The Trust strongly objects to the current proposal of constructing a bridge across the West Basin of Lake Burley Griffin. This objection has the full consensus of the Trust’s Heritage Committee and members of its Expert Advisory Panel. Collectively these people represent expertise and long experience in: heritage management & assessment, architecture, landscape architecture, urban design and history. The reasons for our objection are outlined below. It should be noted however that the National Trust has no objection to a more suitably designed commemorative place celebrating the contributions that immigrants have made and still make to the culture of Australia. 1. National Trust The ACT National Trust, with a membership of 1,600 is part of the National Trust movement in Australia representing 80,000 members. Our charter states: • Our Vision is to be an independent and expert community leader in the conservation of our cultural and natural heritage. • Our Purpose is to foster public knowledge about, and promote the conservation of, places and objects that are significant to our heritage. • Our Organisation is a not‐for‐profit organisation of people interested in understanding and conserving heritage places and objects of local, national and international significance in the ACT region. -

Strategic Review of Recreational Facilities Around Lake Burley Griffin Final Report

STRATEGIC REVIEW OF RECREATIONAL FACILITIES AROUND LAKE BURLEY GRIFFIN FINAL REPORT PREPARED FOR ACT ROWING STRATEGIC REVIEW OF RECREATIONAL FACILITIES AROUND LAKE BURLEY GRIFFIN - FINAL REPORT PREPARED FOR ACT ROWING PAGE 2 OF 75 | CB RICHARD ELLIS (V) PTY LTD | CANBERRA | NOVEMBER 10 | MID 182439 STRATEGIC REVIEW OF RECREATIONAL FACILITIES AROUND LAKE BURLEY GRIFFIN - FINAL REPORT PREPARED FOR ACT ROWING Table of Contents Table of Figures EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 FIGURE 1 – LAKE BURLEY GRIFFIN WITHIN A LOCAL CONTEXT FIGURE 2 - WALTER BURLEY GRIFFIN'S LAKE 1 INTRODUCTION 5 FIGURE 3 - WATER DEPTHS ACROSS LAKE BURLEY GRIFFIN 2 LAKE BURLEY GRIFFIN 6 FIGURE 4 - THE DIFFERENT CHARACTERS OF THE LAKE - YARRALUMLA BEACH 3 METHODOLOGY 10 FIGURE 5 - THE DIFFERENT CHARACTERS OF THE LAKE - COMMONWEALTH PLACE FIGURE 6 - LAKE BURLEY GRIFFIN IN AN ACT CONTEXT 4 RECREATIONAL ACTIVITIES ON AND AROUND LAKE BURLEY GRIFFIN 11 FIGURE 7 - MURRAY COD AND LATHAMS/JAPANESE SNIPE 5 CONSULTATION WITH STAKEHOLDERS 12 FIGURE 8 - METHODOLOGY FIGURE 9- MAIN SHARED RECREATIONAL PATHS AROUND THE LAKE (IN BLUE) 6 KEY THEMES IDENTIFIED FROM CONSULTATION 13 FIGURE 10 - 2008 BICYCLE TRAFFIC COUNTS 7 IDENTIFICATION AND ASSESSMENT OF EXISTING FACILITIES 15 FIGURE 11 - NARROW PATH AT LENNOX GARDENS 8 OPTIONS TO ADDRESS PROPOSED ACTIONS 26 FIGURE 12 - DISTRIBUTION OF PUBLIC FACILITIES (NCA) FIGURE 13 - TOILETS AT LOTUS BAY 9 CONCLUSION 36 FIGURE 14 - PICNIC FACILITIES - LENNOX GARDENS APPENDIX 1 – SUMMARY OF RELEVANT POLICY DOCUMENTS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR RECREATIONAL FIGURE 15 - -

What's New in Canberra

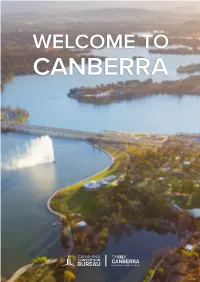

WHAT’S NEW IN CANBERRA CANBERRA CONVENTION BUREAU INVITES YOU TO CANBERRA Welcome to Canberra, Australia’s capital and a city of brilliant possibilities. Canberra is a world city, abundant with prestigious establishments and national treasures, such as the Australian War Memorial, the National Gallery of Australia, and Australian Parliament House. We have a rich history of sporting achievements, political events and Indigenous culture, and we look forward to sharing it with you. Canberra is a planned and congestion-free city where domestic planners can safely bring their future business events, offering a controlled return to business activity. Canberra has been the least impacted city in Australia throughout COVID-19, and Canberra Airport is now more connected than ever to domestic destinations, with increased air routes around Australia. Canberra is ever evolving. Popular precincts, such as NewActon, Braddon, Manuka and Kingston, buzz with activity. Pop-up stores, award-winning architecture, lively brewpubs, cultural festivals, music and public art are at the heart of our city, which has something to offer everyone. Canberra is an accessible, planned city with a serene landscape and surrounded by mountains, forests, rivers and lakes, featuring a kaleidoscope of colours and experiences that unfold in harmony with four distinct seasons. With the help of the Canberra Convention Bureau team, you can access all of Canberra’s unique offerings to design an event program that will inform, entertain, inspire and impress. Our capital is already returning to the positivity stemming from a well-managed confident world city, and we look forward to sharing it with you in person. -

Explore- Your Free Guide to Canberra's Urban Parks, Nature Reserves

ACT P Your free guide to Canberra's urban parks, A E R C I K V S R A E Parks and Conservation Service N S D N nature reserves, national parks and recreational areas. C O O I NSERVAT 1 Welcome to Ngunnawal Country About this guide “As I walk this beautiful Country of mine I stop, look and listen and remember the spirits The ACT is fortunate to have a huge variety of parks and recreational from my ancestors surrounding me. That makes me stand tall and proud of who I am – areas right on its doorstep, ranging from district parks with barbeques a Ngunnawal warrior of today.” and playgrounds within urban areas through to the rugged and Carl Brown, Ngunnawal Elder, Wollabalooa Murringe majestic landscape of Namadgi National Park. The natural areas protect our precious native plants, animals and their habitats and also keep our water supply pure. The parks and open spaces are also places where residents and visitors can enjoy a range of recreational activities in natural, healthy outdoor environments. This guide lists all the parks within easy reach of your back door and over 30 wonderful destinations beyond the urban fringe. Please enjoy these special places but remember to stay safe and follow the Minimal Impact Code of Conduct (refer to page 6 for further information). Above: "Can you see it?"– Bird spotting at Tidbinbilla Nature Reserve. AT Refer to page 50 for further information. Left: Spectacular granite formations atop Gibraltar Peak – a sacred place for Ngunnawal People. Publisher ACT Government 12 Wattle Street Lyneham ACT 2602 Enquiries Canberra Connect Phone: 13 22 81 Website www.tams.act.gov.au English as a second language Canberra Connect Phone: 13 22 81 ISBN 978-0-646-58360-0 © ACT Government 2013 Disclaimer: Every effort has been made to ensure that information in this guide is accurate at the time of printing. -

Memorialising the Past: Is There an Aboriginal Way?

Memorialising the Past: Is there an Aboriginal Way? BRONWYN BATTEN AND PAUL BATTEN n Australia, men of European background dominate I memorials. This dominance is largely a product of the times in which the majority of memorials were created between 1800 and the post WWII era.1 In these times, the focus of history was on politics and warfare both of which were the ‘stages’ on which the lives of great men were played out.2 In the ‘post- modern’ era, the practice of history has expanded to incorporate not only the ‘achievements of great men but of ordinary people, especially those minority or disadvantaged groups supposedly outside the mainstream’.3 Whilst the study of history has expanded to include minority groups such as Australia’s Indigenous people, the field of heritage interpretation is only beginning to engage with diverse perspectives of the Australian past.4 Similarly, although there Public History Review Vol 15 (2008): 92–116 © UTSePress and the authors Public History Review | Batten & Batten has been a growth in memorialisation in recent times,5 it is only relatively recently that memorials have begun to engage with the history of minority groups and in particular Indigenous Australians.6 The idea of memorialisation is seen by some people as being ‘foreign’ to Australian Indigenous cultures. This is particularly relevant to the so-called ‘European’ style of memorialisation generally adopted in Australia that has a classical lineage such as stone and bronze statues, sculptures and pillars. If Indigenous people had memorials it was assumed that places within the landscape itself served the memorial function and thus they were a ‘natural’ form of memorial. -

Canberra Yacht Club Submission

Canberra Yacht Club PO Box 7169 Yarralumla 2600 Tel (02) 6273 4777 Fax (02) 6273 7177 Mariner Pl, Yarralumla ACT email: [email protected] Website: canberrayachtclub.com.au ( ACT Sailing Inc T/A) ABN 93 090 967 514 26 March 2009 Committee Secretary Joint Standing Committee on the National Capital and External Territories Department of House of Representatives PO Box 6021 Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 AUSTRALIA JOINT STANDING COMMITTEE ON THE NATIONAL CAPITAL AND EXTERNAL TERRITORIES INQUIRY INTO THE IMMIGRATION BRIDGE AUSTRALIA PROPOSAL CANBERRA YACHT CLUB (CYC) SUBMISSION The enclosed submission from the Canberra Yacht Club is forwarded for the Joint Standing Committee’s consideration. The Canberra Yacht Club welcomes the Committee’s inquiry and the opportunity to make this submission. The opportunity to amplify the comments in the submission at the Committee’s hearing is also welcomed. Graham Giles Commodore Enclosure: CYC Submission to the Joint Standing Committee on the National Capital and External Territories Inquiry into the Immigration Bridge Australia Proposal JOINT STANDING COMMITTEE ON THE NATIONAL CAPITAL AND EXTERNAL TERRITORIES INQUIRY INTO THE IMMIGRATION BRIDGE AUSTRALIA PROPOSAL CANBERRA YACHT CLUB SUBMISSION Summary The Canberra Yacht Club (CYC) supports the proposition that there is a strong case for the construction in Canberra of a very significant national memorial to celebrate all that immigration has added to Australia’s national life. However, as a major user of the lake the CYC’s position regarding the Immigration Bridge proposal is that: a the proposal that a bridge be constructed at this location is derived from unvalidated Griffin Legacy Strategic Initiatives, and has not been subject to the proper scrutiny, including public consultation, that is warranted for such a significant infrastructure item. -

(NCCA) 10 National Forum Pilgrimage of Justice and Peace

National Council of Churches in Australia (NCCA) 10th National Forum Pilgrimage of Justice and Peace – solidarity with our First Nations Start and End: Australian Centre for Christianity and Culture (ACC&C) Sunday 23 June, 2019 – 4PM Front cover design from “Invasion” by artist John “Munnari” Hammond A’Hang © Presented to the NCCA by Aboriginal and Islander Participants at the NCCA Inaugural Forum, Canberra 14 July1994 ‘Blessed are those, whose strength is in you, whose hearts are set on pilgrimage’ (Ps84:5) Pilgrimage of Justice and Peace Station 1 Mural Wall, Australian Centre for Christianity and Culture (ACC&C) Gathering Prayer God of Love, You are the Creator of this land and of all good things. Our hope is in you because you gave your Son Jesus to reconcile the world to you. We pray for your strength and grace to forgive, accept and love one another, as you love us and forgive and accept us in the sacrifice of your Son. Amen1 Acknowledgement of Country (say altogether) We acknowledge the Ngambri and Ngunnawal people, whom God has placed as the original custodians of this place on which we meet. We acknowledge the wisdom of their Elders, both past and present and honour their continuing culture, and pray that we might all work together for reconciliation and justice in this nation. Introduction to the Pilgrimage of Justice and Peace2 We stand here at the Mural wall, the starting place for our Pilgrimage of Justice and Peace. The Mural Wall represents a painting depicting the Holy Spirit in Our Land by the late renowned Elder, Lawman and painter of the Gija People (East Kimberley), Hector Jandany. -

Cycling Loops

Do the Zoo! Open 9.30am to 5.00pm NOW YOU’VE CYCLED AROUND THE LAKE, every day WHY NOT SAIL ON IT? (except for Christmas Day) Scrivener Dam, Lady Denman Drive, NO BOAT LICENCE REQUIRED Canberra ACT Phone: 02 6287 8400 www.nati onalzoo.com.au Kings Ave PARLIAMENT HOUSE Brisbane Ave Eastlake Parade 25 Wentworth Ave On the Western Loop 30 Telopea Park WESTERNDiscover LOOP the new CENTRAL LOOP EASTERN LOOP This 16km journey takes riders past the National Museum Known as the ‘bridge to bridge’, this 4.9km loop from This 9km route takes riders past the Kingston Foreshore of AustraliaVisitCanberra and the National Arboretum Canberra, app. across Kings Avenue Bridge to Commonwealth Avenue Bridge takes in precinct towards Fyshwick and through the Jerrabomberra Scrivener Dam and past the National Zoo & Aquarium and the the Parliamentary Triangle, home to many of the city’s national Wetlands Nature Reserve, returning back towards the WhetherGovernment you’re House lookingLookout. Itfor continues something on through to do the nearby leafy attractions, and is popular with locals and visitors alike, lake’s Central Basin. Westbourne Woods near the Royal Canberra Golf Club and especially on weekends. You will be riding along the R G Menzies Cycling time: up to 1 hour – mostly flat. orthen want past theto exploreCanberra Yachtthe region, Club and withacross a Commonwealthsingle tap the and Australian of the Year walk. Avenueapp Bridge. turns your phone into a local guide. Cycling time: up to 40 minutes – mostly flat. Cycling time: up to 1.5 hours – some -

Muggera Dance for Reconciliation

THEIssue 6/June 2019 EASTLAKERThe-Eastlaker@facebook [email protected] www.theeastlaker.com.au A free, bimonthly paper serving the inner south east Canberra suburbs of Barton, Forrest, Fyshwick, Griffith, Kingston, Manuka, Narrabundah, Red Hill Conservator finds in favour of Eastlake community group Winter activities at Canberra Heritage listing for Red Hill Manuka tree/ District News 3 reports/ Community News 6 Glassworks/ Art+Design 13 Campsite/ History Notes 15 Access Canberra is too busy, Courage in speaking truth to Achievements, challenges at Dragon boat racing gaining carers don’t care, District News 4 power/ Views & Letters 9 Wetlands/ Environment 14 popularity/ Sports Reports 16 Part of a comprehensive program of events to celebrate ACT Reconciliation Day on Monday 27 May Muggera dance for Reconciliation The Muggera dance group’s performance at the National Museum of Australia was part of a comprehensive program of events to celebrate ACT Reconciliation Day on Monday 27 May. It also included a morning smoking ceremony at Reconciliation Place, Parkes, and dance and voice performances and displays at Glebe Park THEEASTLAKER District News 2 Issue 6/June 2019 The-Eastlaker@facebook [email protected] www.theeastlaker.com.au Gosse St residents Planners thumb their nose at Transport Canberra and City Services’ waste proposals want co-operation Transforming Fyshwick into waste dump By Barbara Moore There is an Australia wide waste recycling and stockpiling crisis as India has joined China in banning the importation of plastics and contaminated waste. On 10 May 2019 Australia was one of more than 180 coun- tries signing an amendment to the Basel Agreement with a deal aimed at restricting shipments of hard-to-recycle plastic waste to poorer countries. -

Mr Peter Dalton (PDF 44KB)

Submission to the Joint Standing Committee on the National Capital and External Territories Inquiry into the Immigration Bridge Australia Proposal Submission by Peter J Dalton – Canberra resident since 1976. I wish to register my firm opposition to the construction of the pedestrian footbridge proposed by Immigration Bridge Australia. My opinions are drawn from attendance at several meetings with officers of the NCA, meetings with Andrew Baulch of IBA and some of his committee members, the content of the IBA website, discussions with the committee of the Canberra Yacht Club and with members of a sub committee established by the NCA for the purposes of community consultation called the Lake Users Group. In Summary: 1 I believe the process adopted by Immigration Bridge Australia is flawed, inappropriate and is seriously lacking in proper public consultation by IBA and by the NCA. Claims that it was drawn in the original plans of Walter Burley Griffin are misleading and the particular footbridge is not in the interests of the people of Canberra, let alone in the interests of the lake users. It will ruin the foreshore and is in conflict with several other existing objectives of the NCA. 2 The process adopted by IBA to raise funds is open to question on matters of honesty as it contains extravagant claims, some of which are unsubstantiated. The IBA advertisements and web site information imply that the plans for the bridge have been fully designed, approved and that they will proceed once members of the public pay for plaques. This method of publicity serves to place the Commonwealth in an invidious position whereupon it could be subject to pressure to agree with the construction without due planning process, without suitable public approval and without a study to determine actual need.