Evangelist Revivalist Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Red-Tie Bill and the Wingless Bird: Tar Heel Baptists and the Evolution

The Daily Advance, which devoted an average of four full-page Red-Tie Bill and the Wingless Bird: columns a day to the spectacle, glowed with the glory of it all. "The Tar Heel Baptists and the evangelist's grip on the city," wrote Herbert Peele, is almost breathtaking .. The revival is the topic of conversation wherever one Evolution Controversy goes. ... The barber in h1~ chair, the salesman behind his counter, the executive at his desk,, the worker ~t ~1s bench, the laborer at his task are one and all thinking Tom Parramore and talking about religion. 0. SAUNDERS, the puckish editor of the Elizabeth City Inde• And what was the inspirational message that Pasquotank County W;pendent, ·was after the revivalists fang and claw before they could was flocking to the tabernacle twice a day, seven days a week, to hear? get their tabernacle up. He predicted that Elizabeth City was going to It was direct, simple, clear, dramatic: the world, Ham assured his have a "red-hot, rip-snorting, hell-raising, sin-busting carnival of evan• audiences, was about to come to an end. The whole temple of man's gelism" that would last for eight weeks or "as Jong as the town stands wordly achievement-all his cities, his industry, his art, his science, his for it." He declared that Evangelist Mordecai Ham's main business government-were at the brink of an utter and complete destruction there was to work on the emotions of the ignorant and then skip town from which there was no earthly or heavenly hope of being spared. -

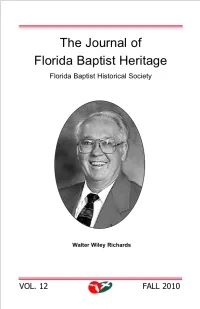

FBHS-Journal-2010.Pdf

The Journal of Florida Baptist Heritage Florida Baptist Historical Society Published by the FLORIDA BAPTIST HISTORICAL SOCIETY Dr. Jerry M. Windsor, Secretary-Treasurer 5400 College Drive Graceville, Florida 32440 Board of Directors y The State Board of Missions of the Florida t e i c Baptist Convention elects the Board of e o g Directors. S l a a t c i i Rev. Joe Butler r r o t Director of Missions, Black Creek Association e s Mrs. Elaine Coats i H H t Fernandina Beach t s i t Mrs. Clysta De Armas s p i a Port Charlotte t B p Mr. Don Graham a a d Graceville i r B o Dr. Thomas Kinchen l F President, The Baptist College of Florida a e d h t Mrs. Dori Nelson i f r Miami o o l l Dr. Paul Robinson a n F Pensacola r u Rev. Guy Sanders o J Pastor, First Baptist Church, New Port Richey Dr. John Sullivan Executive Director-Treasurer Florida Baptist Convention Cover: Dr. W. Wiley Richards has been preach- ing for 56 years, taught for 36 years and has What We Can Learn about Pastoral Preaching from served 48 interims. Dr. Jerry Oswalt......................................................116 Ed Scott Jerry Windsor-A Passion to Preach, a Burden to Teach Introduction ................................................................4 Preachers ................................................................127 Jerry M. Windsor Joel R. Breidenbaugh The 1885 Preaching of Nathan A. Williams ..............6 Dr. W. Wiley Richards: He Came Teaching...........139 Thomas Field Roger C. Richards A Historical Study of Evangelist Mordecai F. Ham’s 1905-1939 Florida Meetings....................................16 s Jerry Hopkins s t t n Charles Bray Williams n e e t Greek Scholar, Pastor, Preacher...............................28 t n Charlotte Williams Sprawls n o o C The Preaching of Charles Roy Angell C “A Master Collector and Teller of Stories”..............68 Jerry E. -

Key Officers List

United States Department of State Telephone Directory This customized report includes the following section(s): Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED) 5/24/2017 Provided by Global Information Services, A/GIS Cover UNCLASSIFIED Key Officers of Foreign Service Posts Afghanistan GSO Jay Thompson RSO Jan Hiemstra AID Catherine Johnson KABUL (E) Great Massoud Road, (VoIP, US-based) 301-490-1042, Fax No working Fax, INMARSAT Tel 011-873-761-837-725, CLO Kimberly Augsburger Workweek: Saturday - Thursday 0800-1630, Website: ECON Jeffrey Bowan kabul.usembassy.gov EEO Daniel Koski FMO David Hilburg Officer Name IMO Meredith Hiemstra DCM OMS vacant IPO Terrence Andrews AMB OMS Alma Pratt ISO Darrin Erwin Co-CLO Hope Williams ISSO Darrin Erwin DCM/CHG Dennis W. Hearne FM Paul Schaefer HRO Dawn Scott Algeria INL John McNamara MGT Robert Needham ALGIERS (E) 5, Chemin Cheikh Bachir Ibrahimi, +213 (770) 08- MLO/ODC COL John Beattie 2000, Fax +213 (21) 60-7335, Workweek: Sun - Thurs 08:00-17:00, POL/MIL John C. Taylor Website: http://algiers.usembassy.gov SDO/DATT COL Christian Griggs Officer Name TREAS Tazeem Pasha DCM OMS Susan Hinton US REP OMS Jennifer Clemente AMB OMS Carolyn Murphy AMB P. Michael McKinley Co-CLO Julie Baldwin CG Jeffrey Lodinsky FCS Nathan Seifert DCM vacant FM James Alden PAO Terry Davidson HRO Carole Manley GSO William McClure ICITAP Darrel Hart RSO Carlos Matus MGT Kim D'Auria-Vazira AFSA Pending MLO/ODC MAJ Steve Alverson AID Herbie Smith OPDAT Robert Huie CLO Anita Kainth POL/ECON Junaid Jay Munir DEA Craig M. Wiles POL/MIL Eric Plues ECON Dan Froats POSHO James Alden FMO James Martin SDO/DATT COL William Rowell IMO John (Troy) Conway AMB Joan Polaschik IPO Chris Gilbertson CON Stuart Denyer ISO Wally Wallooppillai DCM Lawrence Randolph POL Kimberly Krhounek PAO Ana Escrogima GSO Dwayne McDavid Albania RSO Michael Vannett AGR Charles Rush TIRANA (E) 103 Rruga Elbasanit, 355-4-224-7285, Fax (355) (4) 223 CLO Vacant -2222, Workweek: Monday-Friday, 8:00am-4:30 pm, Website: EEO Jake Nelson http://tirana.usembassy.gov/ FMO Rumman Dastgir IMO Mark R. -

Creationism in Twentieth-Century America: the Antievolution Pamphlets of William Bell Riley William Vance Trollinger University of Dayton, [email protected]

University of Dayton eCommons History Faculty Publications Department of History 1995 Creationism in Twentieth-century America: The Antievolution Pamphlets of William Bell Riley William Vance Trollinger University of Dayton, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/hst_fac_pub Part of the History Commons eCommons Citation Trollinger, William Vance, "Creationism in Twentieth-century America: The Antievolution Pamphlets of William Bell Riley" (1995). History Faculty Publications. 5. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/hst_fac_pub/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. INTRODUCTION It is difficult to overstate William Bell Riley's importance to the early fundamentalist movement; it is well-nigh impossible to exaggerate his prodigious energy. In the years between the world wars, when he was in his 60s and 70s and pastor of a church with thousands of members, Riley founded and directed the first inter denominational organization of fundamentalists, served as an active leader of the fundamentalist faction in the Northern Bap tist Convention, edited a variety of fundamentalist periodicals, wrote innumerable books and articles and pamphlets (including, in the less-polemical vein, a forty-volume exposition ofthe entire Bible), presided over a fundamentalist Bible school and its ex panding network of churches, and masterminded a fundamental ist takeover of the Minnesota Baptist Convention. Besides all this, in these years William Bell Riley also established himself as one ofthe leading antievolutionists in America. -

80513 Bibliography

8 80513 BIBLIOGRAPHY Ahlstrom, Sydney E. A Religious History of the American People. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1972. Allen, Roland. Missionary Methods: St. Paul’s or Ours? Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1962. __________. The Spontaneous Expansion of the Church. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1962. Alexander, Archibald. The Log College. Edinburgh: Banner of Truth Trust, 1968. Anderson, Neil, and Elmer L. Towns. Rivers of Revival: How God is Moving & Pouring Himself Out on His People Today. Ventura, CA: Regal, 1997. Arn, Win, Elmer Towns, and Peter Wagner. Church Growth: State of the Art. Wheaton: Tyndale, 1989. Autrey, C. E. Renewals Before Pentecost. Nashville: Broadman, 1968. ________. Revivals of the Old Testament. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1960. Baer, Hans A. African-American Religion in the Twentieth Century: Varieties of Protest and Accommodation. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1992. Bahr, Robert. Least of All Saints: The Story of Aimee Semple McPherson. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1979. Bainton, Roland. Yale and the Ministry. New York: Harper, 1957. Baker, Ernest. The Revivals of the Bible. London: Kingsgate Press, 1906. Banks, Robert J. Paul’s Idea of Community: The Early Church Houses in Their Historical Setting. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1994. Barrett, David B. Evangelize! A Historical Survey of the Concept. Birmingham, AL: New Hope, 1987. Beardsley, Frank G. A History of American Revivals. New York: American Tract Society, 1904. Beasley-Murray, Paul, and Alan Wilkinson. Turning the Tide: An Assessment of Baptist Church Growth in England. London: Bible Society, 1981. Beere, Joel R. Puritan Evangelism—A Biblical Approach. Grand Rapids: Reformation Heritage Books, 1999. Blumhofer, Edith L. -

Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED)

United States Department of State Telephone Directory This customized report includes the following section(s): Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED) 9/13/2021 Provided by Global Information Services, A/GIS Cover UNCLASSIFIED Key Officers of Foreign Service Posts Afghanistan FMO Inna Rotenberg ICASS Chair CDR David Millner IMO Cem Asci KABUL (E) Great Massoud Road, (VoIP, US-based) 301-490-1042, Fax No working Fax, INMARSAT Tel 011-873-761-837-725, ISO Aaron Smith Workweek: Saturday - Thursday 0800-1630, Website: https://af.usembassy.gov/ Algeria Officer Name DCM OMS Melisa Woolfolk ALGIERS (E) 5, Chemin Cheikh Bachir Ibrahimi, +213 (770) 08- ALT DIR Tina Dooley-Jones 2000, Fax +213 (23) 47-1781, Workweek: Sun - Thurs 08:00-17:00, CM OMS Bonnie Anglov Website: https://dz.usembassy.gov/ Co-CLO Lilliana Gonzalez Officer Name FM Michael Itinger DCM OMS Allie Hutton HRO Geoff Nyhart FCS Michele Smith INL Patrick Tanimura FM David Treleaven LEGAT James Bolden HRO TDY Ellen Langston MGT Ben Dille MGT Kristin Rockwood POL/ECON Richard Reiter MLO/ODC Andrew Bergman SDO/DATT COL Erik Bauer POL/ECON Roselyn Ramos TREAS Julie Malec SDO/DATT Christopher D'Amico AMB Chargé Ross L Wilson AMB Chargé Gautam Rana CG Ben Ousley Naseman CON Jeffrey Gringer DCM Ian McCary DCM Acting DCM Eric Barbee PAO Daniel Mattern PAO Eric Barbee GSO GSO William Hunt GSO TDY Neil Richter RSO Fernando Matus RSO Gregg Geerdes CLO Christine Peterson AGR Justina Torry DEA Edward (Joe) Kipp CLO Ikram McRiffey FMO Maureen Danzot FMO Aamer Khan IMO Jaime Scarpatti ICASS Chair Jeffrey Gringer IMO Daniel Sweet Albania Angola TIRANA (E) Rruga Stavro Vinjau 14, +355-4-224-7285, Fax +355-4- 223-2222, Workweek: Monday-Friday, 8:00am-4:30 pm. -

Billy Graham: a New Kind of Evangelist

Monday, Oct. 25, 1954 Billy Graham: A New Kind of Evangelist The first one to come forward was a round, sensible-looking housewife with thick glasses. She stood as still and undramatic as if she were waiting to be served at the meat counter. The next was an eleven-year-old boy who kept his head low to hide his tears: a thin girl appeared behind him and put her arm comfortingly on his shoulder. These three were joined by a broad- shouldered young man whose machine-knitted jersey celebrated a leaping swordfish. then by a pretty young Negro woman in her best clothes with a sleeping baby in her arms. Suddenly there were too many to count, standing on the trampled grass in the blaze of lights. Some of them wept quietly, some of them stared at the ground and some looked upward. Above them all stood a tall, blond young man in a double-breasted tan gabardine suit. His handsome, strong-jawed face was drawn and his blue eyes glittered; for a few seconds he gnawed nervously on a thumbnail, and bright sweat covered his high forehead. He was speaking softly, but with an urgency that seemed to tense every muscle of his body: "You can leave here with peace and joy and happiness such as you've never known. You say: 'Well, 'Billy, that's all well and good. I'll think it over and I may come back some night and I'll—' Wait a minute! You can't come to Christ any time you want to. -

LESSON 17 Upper Level – Jesus, What a Friend for Sinners PACING: 1 Day

HYMNS, OUR CHRISTIAN HERITAGE LESSON 17 Upper Level – Jesus, What a Friend for Sinners PACING: 1 day ESSENTIAL QUESTION, BIG IDEA, and STANDARDS: See Introduction to Hymns, Our Christian Heritage. CONCEPT: Christian hymns are a cherished and valuable legacy, expressing the emotions and experiences of God’s people through many centuries. OBJECTIVES: Learn the text and tune of an important hymn of faith. Interpret the spiritual meaning of the hymn. Understand and communicate important facts about the life of the author of the words and/or the composer of the music. VOCABULARY: hymn, hymn writer, hymnal, text, tune, composer, verse, stanza RESOURCES: Links to performances of the hymn “Jesus, What a Friend for Sinners” (none have both text and tune as they are used in our hymnal) ü Matthew Smith, tune is HYFRYDOL (3:39), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t24uLvayvsM ü Mixed choir, tune is HYFRYDOL(4:06), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QdtAtC99rH0 ü Gaither Quartet, a cappella, tune is HYFRYDOL (4:16), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1bzJNfRJC-E ü Orchestral arrangement, tune is HYFRYDOL (4:22), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4BCmkoFx2O8 ü Mountain dulcimer, HOLY MANNA (1:56), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4BNi-NyaqoI ü Bluegrass band, HOLY MANNA with text “Brethren, We Have Met to Worship” (3:00), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=unGEf6RUPPI ü Mormon Tabernacle Men’s Chorus, HOLY MANNA with text “Brethren, We Have Met to Worship” (3:51), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IFmtO4-oogQ ü The Collingsworth Family, HOLY MANNA tune with text “Brethren, We Have Met to Worship” (3:48), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xt3rZxuUgZc ACTIVITIES: ü Either give each student a printed copy of the hymn, display the hymn for the class electronically or have the students find the hymn “Jesus, What a Friend for Sinners” (#187) in the Seventh-day Adventist Hymnal. -

Creation/Evolution

Creation/Evolution Issue XXIV CONTENTS Fall 1988 ARTICLES 1 Formless and Void: Gap Theory Creationism by Tbm Mclver 25 Scientific Creationism: Adding Imagination to Scripture by Stanley Rice 37 Demographic Change and Antievolution Sentiment: Tennessee as a Case Study, 1925-1975 by George E. Webb FEATURES 43 Book Review 45 Letters to the Editor LICENSED TO UNZ.ORG ELECTRONIC REPRODUCTION PROHIBITED About this issue ... In this issue, Tom Mclver again brings his historical scholarship to bear on an issue relevant to creationism. This time, he explores the history of and the major players in the development and promotion of the "gap theory." Rarely do we treat in detail alternative creationist theories, preferring instead to focus upon the young- Earth special creationists who are so politically militant regarding public educa- tion. However, coverage of different creationist views is necessary from time to time in order to provide perspective and balance for those involved in the controversy. The second article compares scripture to the doctrines of young-Earth special crea- tionists and finds important disparities. Author Stanley Rice convincingly shows that "scientific" creationists add their own imaginative ideas in an effort to pseudoscientifically "flesh out" scripture. But why do so many people accept creationist notions? Some have maintained that the answer may be found through the study of demographics. George E. Webb explores that possibility in "Demographic Change and Antievolution Sentiment" and comes to some interesting conclusions. CREATION/EVOLUTION XXIV (Volume 8, Number 3} ISSN 0738-6001 Creation/Evolution, a publication dedicated to promoting evolutionary science, is published by the American Humanist Association. -

Hosanna, Mansei, Or Banzai?

Hosanna, Mansei, or Banzai? Missionary Narratives and the 1919 March First Movement Hajin Jun A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF ARTS WITH HONORS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN March 30, 2011 Advised by Professor Deirdre de la Cruz To my mother and father CONTENTS Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………….…...…ii Figures…………………………………………...…………………………………...………….iii Introduction……………………………………………..…………………………….………….1 1. “Speaking Truth to Power”…………………………………………………………..……..10 2. “Render unto Caesar”……………………………………… ………………………..……..29 3. Discursive Boundaries……………………………………………………………………….60 Epilogue…………………………………………………………………..……………………..84 Bibliography……………………………………...………………………….………………….87 Acknowledgments I would like to express my deepest thanks to those who have supported me throughout the course of this project. First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor Professor Deirdre de la Cruz, whose unflagging encouragement and interest in my thesis helped me see it to completion. I would also like to thank Professor John Carson, who helped me see through the thicket during the first steps of the writing process, Professor Richard Turits, who graciously read drafts and offered valuable feedback, as well as Professor Hussein Fancy, whose course first inspired a love for writing history. I would also like to thank my friends who cheered me on at every step. A special thanks to Danielle Stahlbaum, who always offered a sympathetic ear and carefully combed through the final pages, and to Joseph Ho, whose insights and suggestions provided immeasurable help in editing process. And lastly, to my family, who often had greater faith in me than I did, and whose love knows no bounds. Figures Chapter One Figure 1: Demonstrator attacked by a Japanese gendarme, p. -

CHSA HP2010.Pdf

The Hawai‘i Chinese: Their Experience and Identity Over Two Centuries 2 0 1 0 CHINESE AMERICA History&Perspectives thej O u r n a l O f T HE C H I n E s E H I s T O r I C a l s OCIET y O f a m E r I C a Chinese America History and PersPectives the Journal of the chinese Historical society of america 2010 Special issUe The hawai‘i Chinese Chinese Historical society of america with UCLA asian american studies center Chinese America: History & Perspectives – The Journal of the Chinese Historical Society of America The Hawai‘i Chinese chinese Historical society of america museum & learning center 965 clay street san francisco, california 94108 chsa.org copyright © 2010 chinese Historical society of america. all rights reserved. copyright of individual articles remains with the author(s). design by side By side studios, san francisco. Permission is granted for reproducing up to fifty copies of any one article for educa- tional Use as defined by thed igital millennium copyright act. to order additional copies or inquire about large-order discounts, see order form at back or email [email protected]. articles appearing in this journal are indexed in Historical Abstracts and America: History and Life. about the cover image: Hawai‘i chinese student alliance. courtesy of douglas d. l. chong. Contents Preface v Franklin Ng introdUction 1 the Hawai‘i chinese: their experience and identity over two centuries David Y. H. Wu and Harry J. Lamley Hawai‘i’s nam long 13 their Background and identity as a Zhongshan subgroup Douglas D. -

A New Protestantism Has Come": World War I, Premillennial Dispensationalism, and the Rise of Fundamentalism in Philadelphia

"A New Protestantism Has Come": World War I, Premillennial Dispensationalism, and the Rise of Fundamentalism in Philadelphia Richard Kent Evans Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies, Volume 84, Number 3, Summer 2017, pp. 292-312 (Article) Published by Penn State University Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/663963 Access provided by Temple University (19 Oct 2018 13:57 GMT) “a new protestantism has come” world war i, premillennial dispensationalism, and the rise of fundamentalism in philadelphia Richard Kent Evans Temple University abstract: This article interprets the rise of Protestant fundamentalism through the lens of an influential network of business leaders and theologians based in Philadelphia in the 1910s. This group of business and religious leaders, through insti- tutions such as the Philadelphia School of the Bible and a periodical called Serving and Waiting, popularized the apocalyptic theology of premillennial dispensationalism. As the world careened toward war, Philadelphia’s premillennial dispensational- ist movement grew more influential, reached a global audience, and cemented the theology’s place within American Christianity. However, when the war ended without the anticipated Rapture of believers, the money, politics, and organization behind Philadelphia’s dispensationalist movement collapsed, creating a vacuum that was filled by a new movement, fundamentalism. This article reveals the human politics behind the fall of dispensationalism, explores the movement’s rebranding as fundamentalism, and highlights Philadelphia’s central role in the rise of Protestant fundamentalism. keywords: Religion, fundamentalism, Philadelphia, theology, apocalypse On July 12, 1917, Blanche Magnin, along with twenty other members of the Africa Inland Mission, boarded the steamship City of Athens in New York and set sail for South Africa.