Boyhood: Scenes from Provincial Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 APPENDIX a Waters Assessed for Compliance with Designated Uses

APPENDIX A WATERS ASSESSED FOR COMPLIANCE WITH DESIGNATED USES A - 1 APPENDIX A Waters Assessed For Compliance With Designated Uses The attached tables present lists of rivers, streams, lakes, and estuaries for which water quality data have been assessed and used to determine compliance with designated water uses. EPD considers all water quality related data that is received in its assessment of State waters. The data reviewed for the 2006 305(b) report included EPD monitoring data for rivers and streams, both trend data and intensive survey data, major lakes project data, toxic substances stream monitoring project data, aquatic biomonitoring project data, and coastal monitoring project data. The assessment also included data from other State, Federal, local governments, contracted Clean Lakes projects, electrical utility companies and other groups. A full list of data sources can be found on page A- 13. The lists are divided into three categories; waters supporting designated uses, waters partially supporting designated uses, and waters not supporting designated uses. The lists are organized by water type (rivers/streams, lakes and estuaries). The rivers/streams section is further organized by river basin. The list includes information on the location, data source, designated water use classification, and estimates of stream miles, lake acres or estuary square miles assessed. In addition, for the partial and not supporting lists, information is provided on the criterion violated, potential cause, actions planned to alleviate the problem, estimates of stream miles, lake acres or estuary square miles affected, 303(d) status, and priority. A discussion of the potential cause and actions to alleviate columns along with a discussion of priorities is given below. -

Maine Rivers Study

MAINE RIVERS STUDY Final Report State of Maine Department of Conservation U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Mid-Atlantic Regional Office May 1982 Electronic Edition August 2011 DEPLW-1214 i Table of Contents Study Participants i Acknowledgments iii Section I - Major Findings 1 Section II - Introduction 7 Section III - Study Method and Process 8 Step 1 Identification and Definition of Unique River Values 8 Step 2 Identification of Significant River Resource Values 8 Step 3 River Category Evaluation 9 Step 4 River Category Synthesis 9 Step 5 Comparative River Evaluation 9 Section IV - River Resource Categories 11 Unique Natural Rivers - Overview 11 A. Geologic / Hydrologic Features 11 B. River Related Critical / Ecologic Resources 14 C. Undeveloped River Areas 20 D. Scenic River Resources 22 E. Historical River Resources 26 Unique Recreational Rivers - Overview 27 A. Anadromous Fisheries 28 B. River Related Inland Fisheries 30 C. River Related Recreational Boating 32 Section V - Final List of Rivers 35 Section VI - Documentation of Significant River Related 46 (Maps to be linked to GIS) Natural and Recreational Values Key to Documentation Maps 46 Section VII – Options for Conservation of Rivers 127 River Conservation – Energy Development Coordination 127 Federal Energy Regulatory Commission Consistency 127 State Agency Consistency 128 Federal Coordination Using the National Wild & Scenic Rivers Act 129 Federal Consistency on Coastal Rivers 129 Designation into National River System 130 ii State River Conservation Legislation -

WVWA Ranked List of Rivers

WVWA’s Ranked Lists of Rivers, Streams and Creeks The following two lists are a ranking of river sections by paddling difficulty, from easier to more difficult. The rivers were ranked at a flow that a paddler is likely to encounter at an enjoyable level. The sections of larger rivers were ranked assuming a flow somewhere between 1,000 and 3,000 cfs. The creeks and smaller rivers were ranked with a flow somewhere between 200 and 1,000 cfs. A minimum stage or flow is also listed but was not used for ranking purposes. This minimum level may be easier or more difficult and is only listed to indicate a minimum "doable" level. When a classification appears in parentheses it indicates one rapid which is harder that the rapids on the rest of the run. For example, Class II-III+(IV) indicates that one rapid of class IV difficulty may be expected. An * appearing after a river name indicates that adjoining river mileage may be paddled but the additional mileage is harder and may affect the ranking of the river. An ** appearing after the minimum level indicates that a visual gauge is commonly used and a paddler may have to use a conversion factor to obtain that reading. These ranking began with a compilation of rivers and creeks by WVWA member Turner Sharp. The compilations were sent to 25 WVWA members for ranking. Eleven were returned and were used in these rankings. These ranked lists are an attempt to have a consistent method of labeling rivers by difficulty when organizing a trip schedule. -

St. Vrain and Left Hand Creek

St. Vrain and Left Hand Water Conservancy District Stream Management Plan Request for Proposal A. Proposal Purpose The St. Vrain and Left Hand Water Conservancy District (District), based in Longmont Colorado, is seeking a consultant, or team of consultants (Consultant), to develop the first phase of a Stream Management Plan (SMP) for the St. Vrain Creek watershed. B. Project Background The St. Vrain Creek watershed (which includes Left Hand Creek) is critical to maintaining the health, biodiversity, character, and economy of communities within the region, including Lyons and Longmont. The creek is a stronghold for native transition zone fishes, receives Colorado River transmountain water, hosts one of the country’s largest outdoor industry events, and has its headwaters in Rocky Mountain National Park and the Indian Peaks Wilderness and its confluence in the county with the largest agricultural economy in Colorado. Further, the watershed has a diverse array of stakeholders that use and derive value from the waters including agricultural users, domestic water providers, conservationists, and recreational users. Colorado’s Water Plan (CWP) sets a measurable objective to cover 80 percent of the locally prioritized lists of rivers with stream management plans. CWP used the South Platte Basin Implementation Plan (BIP) to help inform this measurable objective. The South Platte BIP studied a reach of St. Vrain Creek for environmental and recreational opportunities and concluded adequate streamflows may at times be present to achieve environmental and recreational outcomes. However, the BIP further concluded that opportunities for flow improvements may be available, but additional data and studies on flow and its relationships to form and function, aquatic and riparian ecosystems, and recreation are needed. -

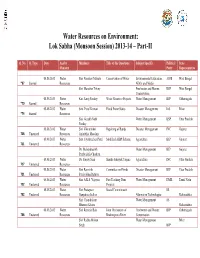

Water Resources on Environment: Lok Sabha (Monsoon Session) 2013-14 – Part-II

Water Resources on Environment: Lok Sabha (Monsoon Session) 2013-14 – Part-II Q. No. Q. Type Date Ans by Members Title of the Questions Subject Specific Political State Ministry Party Representative 08.08.2013 Water Shri Narahari Mahato Conservation of Water Environmental Education, AIFB West Bengal *67 Starred Resources NGOs and Media Shri Manohar Tirkey Freshwater and Marine RSP West Bengal Conservation 08.08.2013 Water Km. Saroj Pandey Water Resource Projects Water Management BJP Chhattisgarh *70 Starred Resources 08.08.2013 Water Smt. Putul Kumari Flood Prone States Disaster Management Ind. Bihar *74 Starred Resources Shri Gorakh Nath Water Management BSP Uttar Pradesh Pandey 08.08.2013 Water Shri Vikrambhai Repairing of Bunds Disaster Management INC Gujarat 708 Unstarred Resources Arjanbhai Maadam 08.08.2013 Water Smt. Jayshreeben Patel Modified AIBP Scheme Agriculture BJP Gujarat 711 Unstarred Resources Dr. Mahendrasinh Water Management BJP Gujarat Pruthvisinh Chauhan 08.08.2013 Water Dr. Sanjay Sinh Sharda Sahayak Yojana Agriculture INC Uttar Pradesh 717 Unstarred Resources 08.08.2013 Water Shri Ramsinh Committee on Floods Disaster Management BJP Uttar Pradesh 721 Unstarred Resources Patalyabhai Rathwa 08.08.2013 Water Shri A.K.S. Vijayan Fast Tracking Dam Water Management DMK Tamil Nadu 722 Unstarred Resources Projects 08.08.2013 Water Shri Prataprao Social Commitment SS 752 Unstarred Resources Ganpatrao Jadhav Alternative Technologies Maharashtra Shri Chandrakant Water Management SS Bhaurao Khaire Maharashtra 08.08.2013 Water -

Headwater Trout Fisheries Ln New Zealand

Headwater trout fisheries ln New Zealand D.J. Jellyman E" Graynoth New Zealand Freshwater Research Report No. 12 rssN 1171-9E42 New Zealmtd, Freshwater Research Report No. 12 Headwater trout fïsheries in New Zealand by D.J. Jellyman E. Graynoth NI\ryA Freshwater Christchurch January 1994 NEW ZEALAND FRBSHWATER RESEARCH REPORTS This report is one of a series issued by NItilA Freshwater, a division of the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research Ltd. A current list of publications in the series with their prices is available from NIWA Freshwater. Organisations may apply to be put on the mailing list to receive all reports as they are published. An invoice will be sent for each new publication. For all enquiries and orders, contact: The Publications Officer NIWA Freshwater PO Box 8602 Riccarton, Christchurch New Zealand ISBN 0-47848326-2 Edited by: C.K. Holmes Preparation of this report was funded by the New Zealand Fish and Game Councils NIWA (the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research Ltd) specialises in meeting information needs for the sustainable development of water and atmospheric resources. It was established on I July 1992. NIWA Freshwater consists of the former Freshwater Fisheries Centre, MAF Fisheries, Christchurch, and parts of the former Marine and Freshwater Division, Department of Scientific and Industrial Research (Hydrology Centre, Christchurch and Taupo Research hboratory). Ttte New Zealand Freshwater Research Report series continues the New Zealand Freshwater Fßheries Report series (formerly the New Zealand. Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, Fisheries Environmental Repon series), and Publications of the Hydrology Centre, Chrßtchurch. CONTENTS Page SUMMARY 1. -

WSRF Grant Applications Shall Conform to the Current 2016 WSRF Criteria and Guidelines

Last Update: August 3, 2017 Colorado Water Conservation Board Water Supply Reserve Fund Grant Application Instructions All WSRF grant applications shall conform to the current 2016 WSRF Criteria and Guidelines. To receive funding from the WSRF, a proposed water activity must be approved by a Roundtable(s) AND the Colorado Water Conservation Board (CWCB). The process for Roundtable consideration and recommendation is outlined in the 2016 WSRF Criteria and Guidelines. The CWCB meets bimonthly according to the schedule on page 2 of this application. If you have questions, please contact the current CWCB staff Roundtable liaison: Arkansas Gunnison | North Platte | Colorado | Metro | Rio Grande | South Platte | Yampa/White Southwest Ben Wade Craig Godbout Megan Holcomb [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 303-866-3441 x3238 303-866-3441 x3210 303-866-3441 x3222 WSRF Submittal Checklist (Required) I acknowledge this request for funding was recommended for CWCB approval by the sponsoring X Basin Roundtable(s). X I acknowledge I have read and understand the 2016 WSRF Criteria and Guidelines. X I acknowledge the Grantee will be able to contract with CWCB using the Standard Contract.(1) Exhibit A (2) X Statement of Work (Word – see Exhibit A Template) (2) X Budget & Schedule (Excel Spreadsheet – see Exhibit A Template) Letters of Matching and/or Pending 3rd Party Commitments(2) Exhibit C (2) Map Photos/Drawings/Reports Letters of Support (3) Certificate of Insurance (General, Auto, & Workers’ Comp.) Contracting Documents Certificate of Good Standing(3) W-9(3) Independent Contractor Form(3) (If applicant is individual, not company/organization) Electronic Funds Transfer (ETF) Form(3) (1) Click “Grant Agreements”. -

1 APPENDIX a Waters Assessed for Compliance with Designated Uses

APPENDIX A WATERS ASSESSED FOR COMPLIANCE WITH DESIGNATED USES A - 1 APPENDIX A Waters Assessed For Compliance With Designated Uses The attached tables present lists of rivers, streams, lakes, and estuaries for which water quality data have been assessed and used to determine compliance with designated water uses. EPD considers all water quality related data that is received in its assessment of State waters. The data reviewed for the 2006 305(b) report included EPD monitoring data for rivers and streams, both trend data and intensive survey data, major lakes project data, toxic substances stream monitoring project data, aquatic biomonitoring project data, and coastal monitoring project data. The assessment also included data from other State, Federal, local governments, contracted Clean Lakes projects, electrical utility companies and other groups. A full list of data sources can be found on page A- 13. The lists are divided into three categories; waters supporting designated uses, waters partially supporting designated uses, and waters not supporting designated uses. The lists are organized by water type (rivers/streams, lakes and estuaries). The rivers/streams section is further organized by river basin. The list includes information on the location, data source, designated water use classification, and estimates of stream miles, lake acres or estuary square miles assessed. In addition, for the partial and not supporting lists, information is provided on the criterion violated, potential cause, actions planned to alleviate the problem, estimates of stream miles, lake acres or estuary square miles affected, 303(d) status, and priority. A discussion of the potential cause and actions to alleviate columns along with a discussion of priorities is given below. -

Colorado Water Conservation Board Flood Recovery Update

Colorado Water Conservation Board Flood Recovery Update Chris Sturm Stream Restoration Coordinator Colorado Water Conservation Board [email protected] ORGANIZATIONAL CHART GOVERNOR DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES COLORADO WATER Colorado State Colorado Division of Colorado Parks Division of Division of CONSERVATION Avalanche Land Oil &Gas Reclamation, Water & Wildlife Forestry BOARD Information Board Conservation Mining, & Resources Center Commission Safety Stream & Lake Watershed & Interstate, Federal Protection Flood Protection & Water Information (In-Stream Flows) Finance Water Supply Section Planning http://cwcb.state.co.us Colorado Water Conservation Board Watershed & Flood Protection Section Grant Programs: Colorado Watershed Restoration Program (CWRP) Invasive Phreatophyte Control Program (IPCP) Colorado Healthy Rivers Fund (CHRF) Fish and Wildlife Resources Fund (FWRF) Senate Bill 14-179 River Restoration grants CWCB Flood Recovery Team Local Stream Coalition Development and Coordination Watershed and Stream Master Planning, Updated hydrology Technical Support for exigent stabilization projects Develop Strategy for Multi-Objective Diversion Design/Construction Program Management- Stream Restoration Design/Implementation Watershed Coalitions •Coalition for the Poudre River Watershed •Estes Valley Watershed Coalition •Big Thompson River Coalition •Little Thompson Watershed Coalition •St. Vrain Creek Coalition •Fourmile Watershed Coalition •Left Hand Watershed Oversight Group •Coal Creek Canyon Watershed Partnership •Middle South Platte River Alliance •El Paso County Regional Watershed Collaborative CWCB’s mission is “to conserve, develop, protect, and manage Colorado’s water for present and future generations” Colorado’s Water Plan Colorado Water Conservation Board December 2015 Watershed Health, Environment, and Recreation Colorado’s Water Plan sets a measurable objective to cover 80 percent of the locally prioritized lists of rivers with stream management plans, and 80 percent of critical watersheds with watershed protection plans, all by 2030. -

Building a Stream Design Team to Deliver Resilience

Building a Stream Design Team ColoradoTo Deliver Emergency Resilience Watershed Protection Program Update St. Vrain Creek Watershed Coalition Board February 2r, 2016 Presentation Overview 1. Building a Foundation for Recovery and Resiliency (CWCB Initiatives) 2. Colorado 2013 EWP Phase II 3. Building a Team to Deliver Resiliency Building a Foundation for Recovery and Resiliency Colorado Water Conservation Board Initiatives Colorado Water Conservation Board CWCB’s mission is “to conserve, develop, protect, and manage Colorado’s water for present and future generations” Non‐consumptive and Consumptive Water Use Colorado’s Water Plan Colorado Water Conservation Board December 2015 Watershed Health, Environment, and Recreation Colorado’s Water Plan sets a measurable objective to cover 80 percent of the locally prioritized lists of rivers with stream management plans, and 80 percent of critical watersheds with watershed protection plans, all by 2030. CWCB Flood Recovery Team • Local Stream Coalition Development and Coordination • Watershed and Stream Master Planning, Updated hydrology • Technical Support for exigent stabilization projects (EWP Phase I) • Develop Strategy for Multi-Objective Diversion Design/Construction • Program Management- Stream Restoration Design/Implementation Watershed Coalitions • Estes Valley Watershed Coalition • Big Thompson River Restoration Coalition • Little Thompson Watershed Restoration Coalition • St. Vrain Creek Coalition • Fourmile Watershed Coalition • Left Hand Watershed Oversight Group • Coal Creek Canyon Watershed Partnership • Middle South Platte River Alliance • El Paso County Regional Watershed Collaborative Colorado 2013 Flood Recovery EWP Phase 2 Emergency Watershed Protection (EWP) Program 2013 Colorado Flood Recovery Phase II NRCS EWP Program Summary • Purpose: Implement emergency recovery measures to protect life and property in watersheds impaired by a natural disaster • Funding: $63.2 mil. -

CA GROW Report 3.18.13Indd.Indd

california ISTOCK TIM PALMER Mill Creek. Cover: Tuolomne River. Letter from the President ivers are the great treasury of biological noted scientists and other experts reviewed the survey design, and diversity in the western United States. state-specifi c experts reviewed the results for each state. RAs evidence mounts that climate is The result is a state-by-state list of more than 250 of the West’s changing even faster than we feared, it outstanding streams, some protected, some still vulnerable. The becomes essential that we create sanctuaries Great Rivers of the West is a new type of inventory to serve the on our best, most natural rivers that will modern needs of river conservation—a list that Western Rivers harbor viable populations of at-risk species— Conservancy can use to strategically inform its work. not only charismatic species like salmon, but a broad range of aquatic and terrestrial This is one of 11 state chapters in the report. Also available are a species. summary of the entire report, as well as the full report text. That is what we do at Western Rivers Conservancy. We buy land With the right tools in hand, Western Rivers Conservancy is to create sanctuaries along the most outstanding rivers in the West seizing once-in-a-lifetime opportunities to acquire and protect – places where fi sh, wildlife and people can fl ourish. precious streamside lands on some of America’s fi nest rivers. With a talented team in place, combining more than 150 years This is a time when investment in conservation can yield huge of land acquisition experience and offi ces in Oregon, Colorado, dividends for the future. -

Legal Protection Schemes for Free-Flowing Rivers in Europe: an Overview

sustainability Article Legal Protection Schemes for Free-Flowing Rivers in Europe: An Overview Tobias Schäfer † Leibniz Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries (IGB), 12587 Berlin, Germany; [email protected] † Present address: WWF Germany, 10117 Berlin, Germany. Abstract: Most of Europe’s rivers are highly fragmented by barriers. This study examines legal protection schemes, that specifically aim at preserving the free-flowing character of rivers. Based on national legislation, such schemes are found in seven European countries: Slovenia, Finland, Sweden, France and Spain as well as Norway and Iceland. The study provides an overview of the individual schemes and their respective scope, compares their protection mechanisms and assesses their effec- tiveness. As Europe’s the remaining free-flowing rivers are threatened by hydropower and other development, the need for effective legal protection, comparable to the designation of Wild and Scenic Rivers in the United States, is urgent. Similarly, any ambitious strategy for the restoration of free-flowing rivers should be complemented with a mechanism for their permanent protection once dams and other barriers are removed. The investigated legal protection schemes constitute a starting point for envisioning a more cohesive European network of strictly protected free-flowing rivers. Keywords: free-flowing rivers; strict protection; protected areas; legal river protection schemes; river nature reserves; dam removal; river restoration; EU Biodiversity Strategy Citation: Schäfer, T. Legal Protection Schemes for Free-Flowing Rivers in Europe: An Overview. Sustainability 1. Introduction 2021, 13, 6423. https://doi.org/ Europe’s last wild rivers and dynamic river landscapes deserve better protection. 10.3390/su13116423 This study examines existing legal protection mechanisms for free-flowing rivers in Europe in order to draw conclusions for more cohesive European policies for river protection.