Winneconne High School 400 N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lower Fox River Lake - Boat Landings

Lower Fox River Lake - Boat Landings Little Lake Butte des Morts Boat Landing Details Map Lake Butte Des Morts -- Ninth Street Boat Launch Details Google Map Little Lake Butte Des Morts -- Menasha - Fritze Park Access Details Google Map Winnebago Pool Lakes - Boat Landings Lake Winnebago Boat Landings Details Map Lake Winnebago -- Brothertown Harbor, Off Cty H Details Google Map Lake Winnebago -- Oshkosh - Otter Street/ Ceape Ave - Carry-In Access Details Google Map Lake Winnebago -- Vinland - Grundman Park - Osh-O-Nee Details Google Map Lake Winnebago – Fisherman’s Park / Taycheedah Details Google Map Lake Winnebago -- Calumet County Boat Launch Details Google Map Lake Winnebago -- Oshkosh - Doemel Point Access - Murdock & Menominee Details Google Map Lake Winnebago -- Oshkosh - Fugleburg Park Details Google Map Lake Winnebago -- Oshkosh - 24th Street Access Details Google Map Lake Winnebago -- Calumet - Columbia Park Details Google Map Lake Winnebago -- Oshkosh - Mill Street Access Details Google Map Lake Winnebago -- Oshkosh - Menominee Park Details Google Map Lake Winnebago -- Black Wolf - Nagy Park Landing, Hwy 45 Details Google Map Lake Winnebago -- Fond Du Lac - Lakeside West Park - Supple Marsh Details Google Map Lake Winnebago -- Sherwood - High Cliff State Park Details Google Map Lake Winnebago -- Columbia Park Boat Access - Google Map Lake Winnebago -- Neenah - South Park Ave., Rec Park Details Google Map Lake Winnebago -- Nagy Point boat landing, - Google Map Lake Winnebago -- Highway 45 Wayside Park Boat Ramp Details Google -

MOVEMENTS of ADULT TAGGED WALLEYES Stqcked Iri Big Lake Butte Des Morts and Spoehr;S Marsh, Wolf Uiver

.. - . Research Report No. 28 (Fisheries) MOVEMENTS OF ADULT TAGGED WALLEYES Stqcked iri Big Lake Butte des Morts and Spoehr;s Marsh, Wolf Uiver By Gordon R. Priegel DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Division of Conservation Bureau of Research ca"ld Planning • INTRODUCTION This report describes the results o£ an investigation of the movements and cUspersal of walleyes captured in Rush Lake during '-Tinter and released in-Go ·v;aters coi:ltaining.an excellent natural walleye population. The waters involved in this study include Lake 1-!innebago and Big Lake Butte des Morts on the 107-mile-long Fox River and Lakes Poygan and Winneconne on the 216-mile-long Wolf River (Figure 1). The Wolf River joins the Fox River in Big Lake Butte des Morts, 10 river miles above Lake Winnebago, and then enters the lake as the Fox River at Oshkosh. The Fox River flows out of Lake Winnebago at Neenah and Menasha and flows 39 river miles north to Green Bay, Lake ~ichigan. Runoff water from 6,000 square miles enters Lake Winnebago. The lake has an area of 137,708 acres with a maximum depth of 21 feet and an average depth of 15.5 feet. It is roughly rectangular in shape: 28 miles long and 10.5 miles wide at its widest point. The small upriver lakes: Poygan, Winneconne and Big Lake Butte des Morts have areas of 14,102; 4,507 and 8,857 acres, respectively. The O.ep~chs of these smaller lakes are similar with maximum depths not exceeding ll feet. The deeper waters are located in the river channels. -

VT Baitfish Regulations Review Team Update

VT Baitfish Regulations Review Update: Comprehensive Evaluation of Fish Pathogens & Aquatic Nuisance Species (ANS) PRESENTATION TO THE VERMONT FISH & WILDLIFE BOARD FEBRUARY 21ST, 2018 TEAM MEMBERS: ADAM MILLER, SHAWN GOOD, TOM JONES, CHERYL FRANK SULLIVAN, TIM BIEBEL VT Baitfish Regulations Review Team Goal Statement: “Review the current VT baitfish regulations with the strong likelihood of coming back to the VT Fish & Wildlife Board with a revised proposal in the future to regulate baitfish use in a manner that is in the best interest of the public and protects VT’s fisheries resources.” Purpose of Today’s Presentation Review research done to date regarding evaluation of fish pathogens (including VHS) in the Northeast and surrounding area Review research done to date regarding evaluation of ANS in the Northeast and surrounding area Discuss recent enforcement action that was taken regarding a mosquitofish detection in imported fathead minnows. Gather feedback from the Board regarding research on evaluation of pathogens (including VHS) and ANS in the Northeast and surrounding area Purpose of Today’s Presentation Review research done to date regarding evaluation of fish pathogens (including VHS) in the Northeast and surrounding area Review research done to date regarding evaluation of ANS in the Northeast and surrounding area Discuss recent enforcement action that was taken regarding a mosquitofish detection in imported fathead minnows. Gather feedback from the Board regarding research on evaluation of pathogens (including VHS) and ANS in the Northeast and surrounding area Fish Pathogens of Concern Emergency Pathogens Not yet detected in Northeast. Can lead to high mortality of stock and large scale die-off of wild stocks. -

Village of Winneconne Comprehensive Outdoor

VillageVillage ofof WinneconneWinneconne ComprehensiveComprehensive OutdoorOutdoor RecreationRecreation PlanPlan 20182018 - 2022- 2022 VILLAGE OF WINNECONNE COMPREHENSIVE OUTDOOR RECREATION PLAN 2018-2022 Adopted January 9, 2018 by Park Board Adopted January 16, 2018 by Village Board Prepared by the Village Park Board, Kirk Ruetten, Director of Public Works and the East Central Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission Trish Nau, Principal Recreation Planner ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The preparation of the Village of Winneconne Comprehensive Outdoor and Recreation Plan 2018-2022 was formulated by the Winneconne Park Commission with assistance from the East Central Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission. MISSION It is the mission of the Village Parks Board to improve the quality of life for all of the Village of Winneconne’s residents and visitors by providing and promoting well-maintained parks, recreational facilities, open space, and urban forest. PARK COMMISSION The Commission is composed of seven citizen members and meets approximately once a month. The Commission works on planning park improvements and with the Director on park and recreation issues. 2017 VILLAGE BOARD John Rogers, President Andy Beiser Chris Boucher Doug Falk Ed Fischer Joe Hoenecke Jeanne Lehr PARK COMMISSION Chris Ruetten, Chair Chris Boucher Jeanne Lehr David Reetz Lani Stanek STAFF Kirk Ruetten, Director of Public Works ABSTRACT TITLE: Village of Winneconne Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan 2018-2022 CONTACT: Trish Nau, ECWRPC Principal Planner AUTHORS: Village Park Board -

Fishing Regulations, 2020-2021, Available Online, from Your License Distributor, Or Any DNR Service Center

Wisconsin Fishing.. it's fun and easy! To use this pamphlet, follow these 5 easy steps: Restrictions: Be familiar with What's New on page 4 and the License Requirements 1 and Statewide Fishing Restrictions on pages 8-11. Trout fishing: If you plan to fish for trout, please see the separate inland trout 2 regulations booklet, Guide to Wisconsin Trout Fishing Regulations, 2020-2021, available online, from your license distributor, or any DNR Service Center. Special regulations: Check for special regulations on the water you will be fishing 3 in the section entitled Special Regulations-Listed by County beginning on page 28. Great Lakes, Winnebago System Waters, and Boundary Waters: If you are 4 planning to fish on the Great Lakes, their tributaries, Winnebago System waters or waters bordering other states, check the appropriate tables on pages 64–76. Statewide rules: If the water you will be fishing is not found in theSpecial Regulations- 5 Listed by County and is not a Great Lake, Winnebago system, or boundary water, statewide rules apply. See the regulation table for General Inland Waters on pages 62–63 for seasons, length and bag limits, listed by species. ** This pamphlet is an interpretive summary of Wisconsin’s fishing laws and regulations. For complete fishing laws and regulations, including those that are implemented after the publica- tion of this pamphlet, consult the Wisconsin State Statutes Chapter 29 or the Administrative Code of the Department of Natural Resources. Consult the legislative website - http://docs. legis.wi.gov - for more information. For the most up-to-date version of this pamphlet, go to dnr.wi.gov search words, “fishing regulations. -

Petition to List US Populations of Lake Sturgeon (Acipenser Fulvescens)

Petition to List U.S. Populations of Lake Sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens) as Endangered or Threatened under the Endangered Species Act May 14, 2018 NOTICE OF PETITION Submitted to U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service on May 14, 2018: Gary Frazer, USFWS Assistant Director, [email protected] Charles Traxler, Assistant Regional Director, Region 3, [email protected] Georgia Parham, Endangered Species, Region 3, [email protected] Mike Oetker, Deputy Regional Director, Region 4, [email protected] Allan Brown, Assistant Regional Director, Region 4, [email protected] Wendi Weber, Regional Director, Region 5, [email protected] Deborah Rocque, Deputy Regional Director, Region 5, [email protected] Noreen Walsh, Regional Director, Region 6, [email protected] Matt Hogan, Deputy Regional Director, Region 6, [email protected] Petitioner Center for Biological Diversity formally requests that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (“USFWS”) list the lake sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens) in the United States as a threatened species under the federal Endangered Species Act (“ESA”), 16 U.S.C. §§1531-1544. Alternatively, the Center requests that the USFWS define and list distinct population segments of lake sturgeon in the U.S. as threatened or endangered. Lake sturgeon populations in Minnesota, Lake Superior, Missouri River, Ohio River, Arkansas-White River and lower Mississippi River may warrant endangered status. Lake sturgeon populations in Lake Michigan and the upper Mississippi River basin may warrant threatened status. Lake sturgeon in the central and eastern Great Lakes (Lake Huron, Lake Erie, Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River basin) seem to be part of a larger population that is more widespread. -

Lower Fox River Lakes - Fish Information

Lower Fox River Lakes - Fish Information Little Lake Butte des Morts – Fish Regulations Fish Population Season Panfish Abundant Open All Year Sturgeon Abundant Closed Catfish Abundant Open All Year Northern Pike Common Open All Year Walleye Common Open All Year Largemouth Bass Present Open All Year Smallmouth Bass Present Open All Year Lake Winnebago – Fish Regulations Fish Population Season Pan fish (bluegill, pumpkinseed, sunfish, crappie and yellow Abundant Open All Year perch) Walleye Abundant Open All Year Lake Sturgeon Abundant Closed Channel Catfish Abundant Open All Year Flathead Catfish Abundant Open All Year Largemouth Bass Common Open All Year Smallmouth Bass Common Open All Year Musky Present May -December Northern Pike Present May to March Lake Butte des Morts – Fish Regulations Fish Population Season Panfish Abundant Open All Year Northern Pike Abundant 5/14 – 3/15 Sturgeon Abundant Closed Channel Catfish Abundant Open All Year Flathead Catfish Abundant 5/14 – 9/14 Largemouth Bass Common Open All Year Musky Present 5/14 - 12/14 Smallmouth Bass Present Open All Year Walleye Present Open All Year Upper Fox River Lakes - Fish Information Lake Winneconne Fish Population Season Panfish Abundant Open All Year Walleye Common Open All Year Sturgeon Abundant Closed Channel Catfish Abundant Open All Year Largemouth Bass Common Open All Year Smallmouth Bass Present Open All Year Musky Present 5/14 - 12/14 Northern Pike Abundant 5/14 – 3/15 Lake Poygan Fish Population Season Panfish Abundant Open All Year Sturgeon Abundant Closed Channel -

Wisconsin Record Fish List Sources: the National Freshwater Fishing Hall of Fame and Verified Wisconsin Record Fish Reports Weight Length Date Species Lbs Oz

WISCONSIN DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES July 2019 FRESHWATER ANGLING RECORDS PO Box 7921 WISCONSIN RECORD FISH Madison, WI 53707-7921 (All Methods) Wisconsin Record Fish List Sources: The National Freshwater Fishing Hall of Fame and Verified Wisconsin Record Fish Reports Weight Length Date Species lbs oz. in. Caught by Address Caught Place Caught County KEPT HOOK AND LINE Alewife 0 2.4 8.125 Eric Geisthardt Milwaukee, WI 05/19/17 Lake Michigan Milwaukee Bass, Largemouth 11 3 none Robert Milkowski 10/12/40 Lake Ripley Jefferson Bass, Smallmouth 9 1 none Leon Stefonek 06/21/50 Indian Lake Oneida Bass, Rock 2 15 none David Harris Waupaca, WI 06/02/90 Shadow Lake Waupaca Bass, Hybrid Striped 13 14.2 28.00 Cody Schutz Marquette, WI 03/16/02 Lake Columbia Columbia Bass, Striped 1 9.3 17.0 Samuel D. Barnes Kenosha, WI 05/24/96 Fox River Kenosha Bass, White 5 3.8 22.25 Jeremy Simmons Gotham, WI 05/05/19 Mississippi River Vernon Bass, Yellow 2 12 16.1 Gary Gehrke Stoughton, WI 02/13/13 Lake Waubesa Dane Bluegill 2 9.8 12.0 Drew Garsow DePere, WI 08/02/95 Green Bay Brown Bowfin 13 1 31.6 Kevin Kelch Wausau, WI 07/19/80 Willow Flowage Oneida Buffalo, Bigmouth 76 8 49.5 Noah Labarge Ottawa, IL 06/21/13 Petenwell Flowage Adams Buffalo, Smallmouth 20 0 30.0 Mike Berg Cedar Lake, IN 12/03/99 Milwaukee River Washington Bullhead, Black 5 8 21.5 William A. Weigus Portage, IN 09/02/89 Big Falls Flowage Rusk Bullhead, Brown 4 2 17.5 Jessica Gales Eureka, WI 07/07/06 Little Green Lake Little Green Bullhead, Yellow 3 5 15.5 Isla M. -

Comprehensive Outdoor Park and Recreation Plan

2013-2017 Comprehensive Outdoor Park and Recreation Plan Winnebago County, Wisconsin Plan Assistance from ECWRPC Adopted 03/xx/2013 DRAFT Website: http://www.co.winnebago.wi.us/parks WINNEBAGO COUNTY COMPREHENSIVE OPEN SPACE AND RECREATION PLAN 2013-2017 Prepared by Winnebago County Parks Department and the East Central Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission Adopted by Committee on: xxxx, 2013 Adopted by County Board on: xxxx, 2013 i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Winnebago County Comprehensive Open Space and Recreation Plan was prepared with assistance from the Winnebago County Board, and the Winnebago County Outdoor Recreation Planning Committee. WINNEBAGO COUNTY BOARD OF SUPERVISORS Mark Harris, County Executive David W. Albrecht , Chairman Patrick Brennand, 1ST Vice Chair Susan T. Ermer, Clerk Nancy Barker Jeanette Diakoff Thomas Egan Paul Eisen Thomas Ellis James Englebert Chuck Farrey Jerold Finch Maribeth Gabert Ronald Grabner Jeff Hall Tim Hamblin Guy Hegg Alfred Jacobson Stan Kline Thomas Konetzke Lawrence Kriescher Kathleen Lennon Susan Locke Donald E. Miller Douglas Nelson Kenneth Neubauer Michael Norton Shiloh Ramos Marissa Reynolds Kenneth Robl Bill Roh Joanne Sievert Harold Singstock Lawrence Smith Claud Thompson Robert J. Warnke Thomas Widener Bill Wingren WINNEBAGO COUNTY PARKS AND RECREATION PLANNING COMMITTEE Jerold Finch Tom Konetzke Harold Singstock Michael Norton Donald Miller Rob Way, Parks Director Other Acknowledgements: Vicky Redlin, Winnebago County Parks Department Staff Trish Nau, Principal Recreation Planner, ECWRPC -

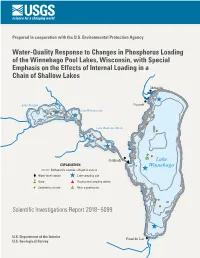

Phosphorus Inputs to the Winnebago Pool Lakes

Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Water-Quality Response to Changes in Phosphorus Loading of the Winnebago Pool Lakes, Wisconsin, with Special Emphasis on the Effects of Internal Loading in a Chain of Shallow Lakes Menasha ^ Lake Poygan Neenah ! ! 2 Lake Winneconne ! ^ ! 3 1 ^ 2 ! 1 3 ! Lake Butte des Morts ! ! 7 ! ! 1 2 ^3 ! ! ! nm Oshkosh X Lake EXPLANATION Winnebago 3 Bathymetric contour—Depth in meters ^ X Water level station ^ Lake sampling site nm Buoy # Gaging and sampling station ! Sediment core site #* River sampling site 6 ! ! Scientific Investigations Report 2018–5099 5 ^ 4 1 3 U.S. Department of the Interior 2 Fond du Lac U.S. Geological Survey Cover figure. Winnebago Pool Lakes, Wisconsin, and their watersheds, with sampling locations identified. Water-Quality Response to Changes in Phosphorus Loading of the Winnebago Pool Lakes, Wisconsin, with Special Emphasis on the Effects of Internal Loading in a Chain of Shallow Lakes By Dale M. Robertson, Benjamin J. Siebers, Matthew W. Diebel, and Andrew J. Somor Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Scientific Investigations Report 2018–5099 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior RYAN K. ZINKE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey James F. Reilly II, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2018 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. -

Winnebago County Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan 2019-2023

WinnebagoTown of Dayton County ComprehensiveComprehensive OutdoorOutdoor RecreationRecreation PlanPlan 2018 - 2022 2019- 2023 * ~ East Central Wisconsin !I,! Regional Planning Commission 0 ~ ECWRPC Calumet • Fond du Lac • Menominee • Outagamie Shawano . Waupaca . Waushara . Winnebago WINNEBAGO COUNTY COMPREHENSIVE OUTDOOR RECREATION PLAN 2019-2023 Recommended March 18, 2019 by Park and Recreation Committee Adopted April 16, 2019 by County Board Prepared by the Park and Recreation Committee and the East Central Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission Trish Nau, Principal Recreation Planner iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The preparation of Winnebago County’s Comprehensive Outdoor and Recreation Plan 2019- 2023 was formulated by the Park and Recreation Committee with assistance from the East Central Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission. COUNTY GOVERNMENT The Park and Recreation Committee is composed of five members and meets approximately once a month. The Committee works on planning parks, recreational, and trail improvements within the County boundaries. 2018-19 WINNEBAGO COUNTY BOARD Thomas J. Konetzke, District 1 Michael A. Brunn, District 2 Thomas Borchart, District 3 Paul Eisen, District 4 Shiloh J. Ramos, District 5 Brian Defferding, District 6 Steven Lenz, District 7 Lawrence W. Smith, District 8 Timothy E. Hogan, District 9 Stephanie J. Spellman, District 10 David Albrecht, District 11 Maribeth Gabert, District 12 Steven Binder, District 13 Jesse Wallin, District 14 Vicki S. Schorse, District 15 Aaron Wojciechowski, District 16 Julie A. Gordan, District 17 Bill Wingren, District 18 Larry Lautenschlager, District 19 Michael Norton, District 20 Robert J. Warnke, District 21 Kenneth Robl, District 22 Harold Singstock, District 23 Andy Buck, District 24 Karen D. Powers, District 25 Susan Locke, District 26 Jim Wise, District 27 Jerry Finch, District 28 Rachel A. -

RESEARCH Report1ss

~ ~ WISCONSIN DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Movements of Adult Lake Sturgeon in the RESEARCH Lake Winnebago System by John Lyons Bureau of Research, Monona REPORT1ss and James J. Kempinger Bureau of Research, Oshkosh Abstract We used data from a long-term tagging program to analyze movement patterns of adult lake sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens) in the Lake Winnebago system, Wisconsin. Of 13,549 adult lake sturgeon tagged between 1952 and 1984, 1 ,633 were recaptured at least once. The spatial and temporal distribution of tagging and recapture reflected the distribution of sampling effort as well as the distribution of lake sturgeon. Most fish recaptured in Lake Winnebago had also been tagged there, but usually not in the same area of the lake. Many fish from Lake Winnebago moved into the Wolf River during the spring to spawn, whereas others moved into the Fox or Embarrass rivers. Lake sturgeon from Lake Poygan also moved into the Wolf River during the spring to spawn. Males tended to spawn every 1 or 2 years and females every 3 or 4 years; most of the fish caught on the spawning grounds were males. Most spawning fish returned to the same area of river each time they spawned. Few fish moved between rivers. Adult lake sturgeon were captured in the Wolf River during the fall as well as the spring. Some of the fall-captured fish might have been permanent residents, but others appeared to be fish from Lake Winnebago that moved into the river during the fall and remained there until they were finished spawning in the spring.