Online Detection of Effectively Callback Free Objects with Applications to Smart Contracts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdp11-40.Pdf

processor handbook digital equipment corporation Copyright© 1972, by Digital Equipment Corporation DEC, PDP, UNIBUS are registered trademarks of Digital Equipment Corporation. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1·1 1.1 GENERAL ............................................. 1·1 1.2 GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS . 1·2 1.2.1 The UNIBUS ..... 1·2 1.2.2 Central Processor 1·3 1.2.3 Memories ........... 1·5 1.2.4 Floating Point ... 1·5 1.2.5 Memory Management .............................. .. 1·5 1.3 PERIPHERALS/OPTIONS ......................................... 1·5 1.3.1 1/0 Devices .......... .................................. 1·6 1.3.2 Storage Devices ...................................... .. 1·6 1.3.3 Bus Options .............................................. 1·6 1.4 SOFTWARE ..... .... ........................................... ............. 1·6 1.4.1 Paper Tape Software .......................................... 1·7 1.4.2 Disk Operating System Software ........................ 1·7 1.4.3 Higher Level Languages ................................... .. 1·7 1.5 NUMBER SYSTEMS ..................................... 1-7 CHAPTER 2 SYSTEM ARCHITECTURE. 2-1 2.1 SYSTEM DEFINITION .............. 2·1 2.2 UNIBUS ......................................... 2-1 2.2.1 Bidirectional Lines ...... 2-1 2.2.2 Master-Slave Relation .. 2-2 2.2.3 Interlocked Communication 2-2 2.3 CENTRAL PROCESSOR .......... 2-2 2.3.1 General Registers ... 2-3 2.3.2 Processor Status Word ....... 2-4 2.3.3 Stack Limit Register 2-5 2.4 EXTENDED INSTRUCTION SET & FLOATING POINT .. 2-5 2.5 CORE MEMORY . .... 2-6 2.6 AUTOMATIC PRIORITY INTERRUPTS .... 2-7 2.6.1 Using the Interrupts . 2-9 2.6.2 Interrupt Procedure 2-9 2.6.3 Interrupt Servicing ............ .. 2-10 2.7 PROCESSOR TRAPS ............ 2-10 2.7.1 Power Failure .............. -

Embedded C Programming I (Ecprogrami)

To our customers, Old Company Name in Catalogs and Other Documents On April 1st, 2010, NEC Electronics Corporation merged with Renesas Technology Corporation, and Renesas Electronics Corporation took over all the business of both companies. Therefore, although the old company name remains in this document, it is a valid Renesas Electronics document. We appreciate your understanding. Renesas Electronics website: http://www.renesas.com April 1st, 2010 Renesas Electronics Corporation Issued by: Renesas Electronics Corporation (http://www.renesas.com) Send any inquiries to http://www.renesas.com/inquiry. Notice 1. All information included in this document is current as of the date this document is issued. Such information, however, is subject to change without any prior notice. Before purchasing or using any Renesas Electronics products listed herein, please confirm the latest product information with a Renesas Electronics sales office. Also, please pay regular and careful attention to additional and different information to be disclosed by Renesas Electronics such as that disclosed through our website. 2. Renesas Electronics does not assume any liability for infringement of patents, copyrights, or other intellectual property rights of third parties by or arising from the use of Renesas Electronics products or technical information described in this document. No license, express, implied or otherwise, is granted hereby under any patents, copyrights or other intellectual property rights of Renesas Electronics or others. 3. You should not alter, modify, copy, or otherwise misappropriate any Renesas Electronics product, whether in whole or in part. 4. Descriptions of circuits, software and other related information in this document are provided only to illustrate the operation of semiconductor products and application examples. -

Operating Systems What Is an Operating System Real-Time

Operating Systems Babak Kia Adjunct Professor Boston University College of Engineering Email: bkia -at- bu.edu ENG SC757 - Advanced Microprocessor Design What is an Operating System z Operating System handles • Memory Addressing & Management • Interrupt & Exception Handling • Process & Task Management • File System • Timing • Process Scheduling & Synchronization z Examples of Operating Systems • RTOS – Real-Time Operating System • Single-user, Single-task: example PalmOS • Single-user, Multi-task: MS Windows and MacOS • Multi-user, Multi-task: UNIX 2 Real-Time Operating Systems z Operating systems come in two flavors, real-time versus non real-time z The difference between the two is characterized by the consequences which result if functional correctness and timing parameters are not met in the case of real-time operating systems z Real-time operating systems themselves have two varieties, soft real-time systems and hard real- time systems z Examples of real-time systems: • Food processing • Engine Controls • Anti-lock breaking systems 3 1 Soft versus Hard Real-Time z In a soft real-time system, tasks are completed as fast as possible without having to be completed within a specified timeframe z In a hard real-time operating system however, not only must tasks be completed within the specified timeframe, but they must also be completed correctly 4 Foreground/Background Systems z The simplest forms of a non real-time operating systems are comprised of super-loops and are called foreground/background systems z Essentially this is an application -

Reentrant Code

Reentrant Code a reentrant procedure can have several calls open to it at the same time in an interrupt environment, different ISRs may call the same routine in a multitasking or multiuser or multithreaded environment, a single copy of a subroutine may be shared by more than one task/user/thread Reentrant Task subroutine A Task B Reentrant Code Characteristics requirements: 1. any parameters or local variables must be on the stack frame 2. registers may be used for parameters and local variables but must be saved on or restored from the stack at beginning/end of the subroutine 3. guarantee that each call of the subroutine will create a separate stack frame to maintain data integrity 4. no self-modifying code Recursion recursive code must be reentrant recursive reentrant but reentrant recursive e.g. calculating 3! using recursion main move.w number,D0 pass the number jsr fact start recursive rtn move.w D0,result store the factorial stop #$2700 number dc.w 3 result ds.w 1 fact link A6,#-2 Stack structure move.w D0,-2(A6) subq.w #1,D0 bne push move.w -2(A6),D0 bra return push jsr fact mulu -2(A6),D0 return unlk A6 rts end main SP ->/////// A much more complex example: X: array [0..30] of words Y: longword Z, ALPHA, N: byte call order is S/R demo(X, Y, Z, ALPHA, N ) N is passed/returned by value, all others are passed by reference demo(X[w:31], Y[l], Z[b], ALPHA[b], N[b]) main CLR.W D2 zero entire word MOVE.B N,D2 N to low byte MOVE.W D2,-(SP) N on stack PEA ALPHA push arguments PEA Z in reverse order PEA Y PEA X JSR demo call -

Java Concurrency in Practice

Java Concurrency in practice Chapters: 1,2, 3 & 4 Bjørn Christian Sebak ([email protected]) Karianne Berg ([email protected]) INF329 – Spring 2007 Chapter 1 - Introduction Brief history of concurrency Before OS, a computer executed a single program from start to finnish But running a single program at a time is an inefficient use of computer hardware Therefore all modern OS run multiple programs (in seperate processes) Brief history of concurrency (2) Factors for running multiple processes: Resource utilization: While one program waits for I/O, why not let another program run and avoid wasting CPU cycles? Fairness: Multiple users/programs might have equal claim of the computers resources. Avoid having single large programs „hog“ the machine. Convenience: Often desirable to create smaller programs that perform a single task (and coordinate them), than to have one large program that do ALL the tasks What is a thread? A „lightweight process“ - each process can have many threads Threads allow multiple streams of program flow to coexits in a single process. While a thread share process-wide resources like memory and files with other threads, they all have their own program counter, stack and local variables Benefits of threads 1) Exploiting multiple processors 2) Simplicity of modeling 3) Simplified handling of asynchronous events 4) More responsive user interfaces Benefits of threads (2) Exploiting multiple processors The processor industry is currently focusing on increasing number of cores on a single CPU rather than increasing clock speed. Well-designed programs with multiple threads can execute simultaneously on multiple processors, increasing resource utilization. -

AN10381 Nesting of Interrupts in the LPC2000 Rev

AN10381 Nesting of interrupts in the LPC2000 Rev. 01 — 6 June 2005 Application note Document information Info Content Keywords nested, reentrant, interrupts, LPC2000 Abstract Details on reentrant interrupt handlers and code examples for the same is provided Philips Semiconductors AN10381 Nesting of interrupts in the LPC2000 Revision history Rev Date Description 01 20050606 Initial version Contact information For additional information, please visit: http://www.semiconductors.philips.com For sales office addresses, please send an email to: [email protected] © Koninklijke Philips Electronics N.V. 2005. All rights reserved. Application note Rev. 01 — 6 June 2005 2 of 14 Philips Semiconductors AN10381 Nesting of interrupts in the LPC2000 1. Introduction This application note provides code examples for effectively handling reentrant interrupt handlers in the LPC2000 devices. The following organization is been adopted for this application note. 1. Interrupt handling overview 2. Nesting of Interrupts 3. Code examples It is assumed for this application note, that the user is familiar with the ARM7TDMI-S architecture. Also, for code examples relating to simple interrupt handling using FIQ and IRQ, please refer to the AN10254_1 application note available online. All the code examples provided in this application note were built on the Keil MicroVision3 ARM compiler (an evaluation version of which is free for download at www.keil.com) 2. Interrupt handling overview 2.1 Interrupt levels in the ARM7 core The ARM7 processor supports two levels of interrupts: Interrupt Request (IRQ) and Fast Interrupt Request (FIQ). ARM recommends only one interrupt source to be classified as an FIQ. All other interrupt sources could be classified as IRQ’s and they could be programmed for reentrancy. -

Threads, IPC, and Synchronization CS 111 Operating Systems Peter Reiher

Operating System Principles: Threads, IPC, and Synchronization CS 111 Operating Systems Peter Reiher CS 111 Lecture 7 Fall 2016 Page 1 Outline • Threads • Interprocess communications • Synchronization – Critical sections – Asynchronous event completions CS 111 Lecture 7 Fall 2016 Page 2 Threads • Why not just processes? • What is a thread? • How does the operating system deal with threads? CS 111 Lecture 7 Fall 2016 Page 3 Why Not Just Processes? • Processes are very expensive – To create: they own resources – To dispatch: they have address spaces • Different processes are very distinct – They cannot share the same address space – They cannot (usually) share resources • Not all programs require strong separation – Multiple activities working cooperatively for a single goal CS 111 – Mutually trusting elements of a system Lecture 7 Fall 2016 Page 4 What Is a Thread? • Strictly a unit of execution/scheduling – Each thread has its own stack, PC, registers – But other resources are shared with other threads • Multiple threads can run in a process – They all share the same code and data space – They all have access to the same resources – This makes the cheaper to create and run • Sharing the CPU between multiple threads – User level threads (with voluntary yielding) CS 111 – Scheduled system threads (with preemption) Lecture 7 Fall 2016 Page 5 When Should You Use Processes? • To run multiple distinct programs • When creation/destruction are rare events • When running agents with distinct privileges • When there are limited interactions and shared resources • To prevent interference between executing interpreters • To firewall one from failures of the other CS 111 Lecture 7 Fall 2016 Page 6 When Should You Use Threads? • For parallel activities in a single program • When there is frequent creation and destruction • When all can run with same privileges • When they need to share resources • When they exchange many messages/signals • When you don’t need to protect them from each other CS 111 Lecture 7 Fall 2016 Page 7 Processes vs. -

CS 33 Week 8 Section 1G, Spring 2015 Prof

CS 33 Week 8 Section 1G, Spring 2015 Prof. Eggert (TA: Eric Kim) v1.0 Announcements ● Midterm 2 scores out now ○ Check grades on my.ucla.edu ○ Mean: 60.7, Std: 15 Median: 61 ● HW 5 due date updated ○ Due: May 26th (Tuesday) ● Lab 4 released soon ○ OpenMP Lab ○ Tutorial on OpenMP ■ http://openmp.org/mp-documents/omp-hands-on-SC08.pdf Overview ● More concurrency ● File I/O ● MT 2 Example: sum int result = 0; void sum_n(int n) { Suppose Louis if (n == 0) { Reasoner tries to result = n; make this code } else { thread safe... sum_n(n-1); result = result + n; } } Example: fib Question: Is there anything wrong with this code? int result = 0; sem_t s; // sem_init(&s,1); void sum_n(int n) { if (n == 0) { P(&s); result = n; V(&s); } else { P(&s); Answer: Yes, deadlock! sum_n(5) calls sum_n(n-1); sum_n(4), but sum_n(4) can't acquire result = result + n; mutex. sum_n(5) can't make progress V(&s); without sum_n(4) - thread is stuck. } } Thread-safe functions Definition: A function is thread-safe if functions correctly during simultaneous execution by multiple threads. [http: //stackoverflow.com/questions/261683/what-is-meant-by-thread-safe-code] Alt: In computer programming, thread-safe describes a program portion or routine that can be called from multiple programming threads without unwanted interaction between the threads. [http://whatis.techtarget.com/definition/thread-safe] Thread-safe functions Typically achieve thread-safety by mechanisms: - Synchronization (ie semaphores/mutexes) - Careful handling of shared data "To write code that will run stably for weeks takes extreme paranoia." (Not actually said by Nixon) Reentrant Functions A "stronger" version of thread-safe (in a sense). -

"Effectively Callback Freeness" for Smart Contracts

Analysis of “Effectively Callback Freeness” for Smart Contracts Trabajo de Fin de Máster Curso 2019–2020 Autor Clara Rodríguez Núñez Directores Elvira Albert Albiol Albert Rubio Gimeno Máster en Métodos Formales en Ingeniería Informática Facultad de Informática Universidad Complutense de Madrid Convocatoria: Julio 2020 Calificación: 10 Analysis of “Effectively Callback Freeness” for Smart Contracts Trabajo de Fin de Máster en Métodos Formales en Ingeniería Informática Autor Clara Rodríguez Núñez Directores Elvira Albert Albiol Albert Rubio Gimeno Máster en Métodos Formales en Ingeniería Informática Facultad de Informática Universidad Complutense de Madrid Dedicatoria A mi abuela, por enseñarme tanto en cada llamada v Agradecimientos En primer lugar, a Elvira y Albert. Gracias por todo lo que he aprendido y disfru- tado estos meses, por el apoyo cuando las cosas no iban bien y por soportarme en cientos de videollamadas, incluso cuando me pasa un tren por encima. Formar parte de un proyecto como este ha sido un autentico privilegio. Gracias también a todos los miembros del grupo COSTA por recibirme tan bien y estar siempre dispuestos a echarme una mano. Gracias a todas las personas que me han hecho disfrutar de las matemáticas y la informática. A los profesores que he tenido durante estos años, gracias por vuestro esfuerzo y pasión por enseñar, habéis sacado una versión de mí que nunca pensé que existiera. A los amigos que he hecho en esta universidad, gracias por ser los mejores compañeros de viaje. Aun nos quedan muchas locuras por hacer, montañas que escalar y partidos donde no tirar. Gracias a mi familia. Cuando era una niña y soñaba con ser investigadora me acompañabais cada fin de semana a buscar fósiles a la montaña de detrás de casa. -

Embedded (Real Time) Operating Systems

Real Time Operating Systems q What is the basic thing we want the OS to do to help us improve worst case latency? Enable multithreading q How? Define an OS time-slice (tick) at which highest priority ‘runnable’ task is continued. Priority function determines response behavior. q Simplest Scheduling algorithm: each task gets at most 1 tick at a time to run. Round Robin Scheduling. Worst case task latency = #tasks*tick. Worst case run time = ticks/task * #tasks q Some properties of such system: liveness, safety, fairness, latency, overhead. q Other niceties: Device Drivers, Synchronization, Message passing, Memory Management CSE466 Autumn ‘00- 1 Features of an Embedded Operating System q Interrupt latency q System call overhead (Various functions…task switch, signal, create, delete) q Memory overhead q Tasks (threads) q Scheduling Algorithms q Communication and synchronization primitives (tools) q Memory Management CSE466 Autumn ‘00- 2 Comparative Real Time OSes Compare to uClinux at ~400Kbytes. what for? What is this? 38us – 280us why the variable? actually 16 semaphores CSE466 Autumn ‘00- 3 Stack Management CSE466 Autumn ‘00- 4 Multitasking – state maintained for each task time slice only Running Runnable one task time slice in this state at a time wait() delete() signal() create() delete() Blocked Deleted system calls CSE466 Autumn ‘00- 5 Programmers View of Tiny OS void tone_isr(void) interrupt … { Advantages: process_tones(); if (!--sliceCount) { •Deterministic response time updateToneParameters(); sliceCount = SliceSize even w/ non deterministic isr_send_signal(MUSIC); } tasks lengths. } void serial_isr(void) interrupt …{ • Incremental development timeCritical(); os_send_signal(SERIAL); } void play(void) _task_ MUSIC { Resources: os_create(SERIAL); while (1) {os_wait(); •Task switching overhead process_next_event();} } •Memory overhead void serial(void) _task_ SERIAL { while (1) {os_wait(); •Use of system timer process_serial_data();} // os_create(MUSIC)? } •Degrades best case response time. -

Exploiting the Laws of Order in Smart Contracts

Exploiting The Laws of Order in Smart Contracts Aashish Kolluri ∗, Ivica Nikolic´ ∗, Ilya Sergey y, Aquinas Hobor ∗ z, Prateek Saxena ∗ ∗School Of Computing, NUS, Singapore zYale-NUS College, Singapore yUniversity College London, United Kingdom Abstract—We investigate a family of bugs in blockchain-based smart contracts have been deployed to Ethereum’s blockchain. smart contracts, which we call event-ordering (or EO) bugs. These Numerous publicly reported attacks have resulted in hundreds bugs are intimately related to the dynamic ordering of contract of millions dollars’ worth of Ether being stolen or otherwise events, i.e., calls of its functions on the blockchain, and enable potential exploits of millions of USD worth of Ether. Known lost [10], [22]. Further, contracts cannot be patched once examples of such bugs and prior techniques to detect them have deployed. This emphasizes the importance of pre-deployment been restricted to a small number of event orderings, typicall 1 security audit and analysis of smart contracts. or 2. Our work provides a new formulation of this general class This paper investigates a class of vulnerabilities in smart of EO bugs as finding concurrency properties arising in long contracts that arise due to their inherent concurrent execution permutations of such events. The technical challenge in detecting our formulation of EO model. Contracts can be invoked by multiple users concur- bugs is the inherent combinatorial blowup in path and state space rently, and the ordering of multiple submitted transactions is analysis, even for simple contracts. We propose the first use of non-deterministically decided by miners through a consensus partial-order reduction techniques, using happen-before relations protocol. -

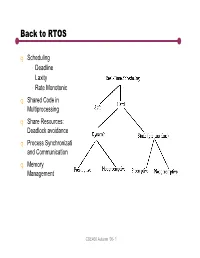

Back to RTOS

Back to RTOS q Scheduling Deadline Laxity Rate Monotonic q Shared Code in Multiprocessing q Share Resources: Deadlock avoidance q Process Synchronization and Communication q Memory Management CSE466 Autumn ‘00- 1 Dynamic Non-preemptive Scheduling os time os time os time music time slice slice slice music time slice…signal slice serial_isr music task music_isr serial music OS deadline serial_isr Char arrives Music task is never signals more than one OS serial task time slice away CSE466 Autumn ‘00- 2 Dynamic Preemptive Scheduling signal T2 signal T1, preempt T2 (time slice not up) ISR T2 Completes T2/lo T1/hi OS Pre-emptive: hi priority tasks preempt low priority task. Advantage: Lower latency, faster response for high priority tasks. Disadvantage: Potential to starve a low priority task Tiny: no priority, round robin only. No starvation. Priority Inversion: when T2 disables interrupts Priority Function: any suggestions? CSE466 Autumn ‘00- 3 Scheduling Algorithms (Priority Functions) q Egalatarian: Round Robin Problem: We my have unused compute resources even though we don’t meet some deadliines … it can be non optimal. Example: system with music task and n non-critical tasks. § if deadline < time_tick * n + music_task then we have a chance to miss the deadline. § If music is higher priority than worst case is: time_tick + music_task q Theory: for a system with N periodic tasks. The system is schedulable if: ΣCi/Pi <= 1 where Ci is seconds or computation per event i and Pi is period of event I whereCi/PiisthefractionoftimespentdealingwithI § Let Ci = .5 and Pi = 2 Ci/Pi = .25 (1/4 of the time) Rate monotonic scheduling: Priority α Frequency At run time: Highest priority task always preempts lowest priority task.