"Central African Republic"?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNHCR Republic of Congo Fact Sheet

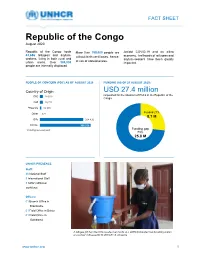

FACT SHEET Republic of the Congo August 2020 Republic of the Congo hosts More than 155,000 people are Amidst COVID-19 and an ailing 43,656 refugees and asylum- without birth certificates, hence, economy, livelihoods of refugees and seekers, living in both rural and asylum-seekers have been greatly at risk of statelessness. urban areas. Over 304,000 impacted. people are internally displaced PEOPLE OF CONCERN (POC) AS OF AUGUST 2020 FUNDING (AS OF 25 AUGUST 2020) Country of Origin USD 27.4 million requested for the situation of PoCs in the Republic of the DRC 20 810 Congo CAR 20,722 *Rwanda 10 565 Funded 27% Other 421 8.1 M IDPs 304 430 TOTAL: 356 926 * Including non-exempted Funding gap 73% 25.8 M UNHCR PRESENCE Staff: 46 National Staff 9 International Staff 8 IUNV (affiliated workforce) Offices: 01 Branch Office in Brazzaville 01 Field Office in Betou 01 Field Office in Gamboma A refugee girl from the DRC washes her hands at a UNHCR-installed handwashing station at a school in Brazzaville © UNHCR / S. Duysens www.unhcr.org 1 FACT SHEET > Republic of the Congo / August 2020 Working with Partners ■ Aligning with the Global Compact on Refugees (GCR), UNHCR in the Republic of the Congo (RoC) has diversified its partnership base to include five implementing partners, comprising local governmental and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), as well as international NGOs. ■ The National Committee for Assistance to Refugees (CNAR), is UNHCR’s main governmental partner, covering general refugee issues, particularly Refugee Status Determination (RSD). Other specific governmental partners include the Ministry of Social and Humanitarian Affairs (MASAH), the Ministries of Justice and Interior (for judicial issues and policies on issues related to statelessness and civil status registration), and the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH). -

Forced Labour at the Frontier of Empires: Manipur and the French Congo”, Comparatif

“Forced Labour at the Frontier of Empires: Manipur and the French Congo”, Comparatif. Yaruipam Muivah, Alessandro Stanziani To cite this version: Yaruipam Muivah, Alessandro Stanziani. “Forced Labour at the Frontier of Empires: Manipur and the French Congo”, Comparatif.. Comparativ, Leipzig University, 2019, 29 (3), pp.41-64. hal-02954571 HAL Id: hal-02954571 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02954571 Submitted on 1 Oct 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Yaruipam Muivah, Alessandro Stanziani Forced Labour at the Frontier of Empires: Manipur and the French Congo, 1890-1914. Debates about abolition of slavery have essentially focused on two interrelated questions: 1) whether nineteenth and early twentieth century abolitions were a major breakthrough compared to previous centuries (or even millennia) in the history of humankind during which bondage had been the dominant form of labour and human condition. 2) whether they express an action specific to western bourgeoisie and liberal civilization. It is true that the number of abolitionist acts and the people concerned throughout the extended nineteenth century (1780- 1914) had no equivalent in history: 30 million Russian peasants, half a million slaves in Saint- Domingue in 1790, four million slaves in the US in 1860, another million in the Caribbean (at the moment of the abolition of 1832-40), a further million in Brazil in 1885 and 250,000 in the Spanish colonies were freed during this period. -

Democratic Republic of Congo Constitution

THE CONSTITUTION OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO, 2005 [1] Table of Contents PREAMBLE TITLE I GENERAL PROVISIONS Chapter 1 The State and Sovereignty Chapter 2 Nationality TITLE II HUMAN RIGHTS, FUNDAMENTAL LIBERTIES AND THE DUTIES OF THE CITIZEN AND THE STATE Chapter 1 Civil and Political Rights Chapter 2 Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Chapter 3 Collective Rights Chapter 4 The Duties of the Citizen TITLE III THE ORGANIZATION AND THE EXERCISE OF POWER Chapter 1 The Institutions of the Republic TITLE IV THE PROVINCES Chapter 1 The Provincial Institutions Chapter 2 The Distribution of Competences Between the Central Authority and the Provinces Chapter 3 Customary Authority TITLE V THE ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COUNCIL TITLE VI DEMOCRACY-SUPPORTING INSTITUTIONS Chapter 1 The Independent National Electoral Commission Chapter 2 The High Council for Audiovisual Media and Communication TITLE VII INTERNATIONAL TREATIES AND AGREEMENTS TITLE VIII THE REVISION OF THE CONSTITUTION TITLE IX TRANSITORY AND FINAL PROVISIONS PREAMBLE We, the Congolese People, United by destiny and history around the noble ideas of liberty, fraternity, solidarity, justice, peace and work; Driven by our common will to build in the heart of Africa a State under the rule of law and a powerful and prosperous Nation based on a real political, economic, social and cultural democracy; Considering that injustice and its corollaries, impunity, nepotism, regionalism, tribalism, clan rule and patronage are, due to their manifold vices, at the origin of the general decline -

United Nations Mission in the Central African Republic and Chad (MINURCAT) / European Union Force (EUFOR)

United Nations Mission in the Central African Republic and Chad (MINURCAT) / European Union Force (EUFOR) Short Mission Brief I. Activity Summary: MINURCAT and EUFOR Overview The United Nations Mission in the Central African Republic and Chad (MINURCAT), active from 2007 through 2010, was challenged from the start by the Chadian government’s minimal consent for a UN presence, which precluded the political processes essential to successful peacekeeping and eventually forced the abrupt closure of the mission. Though MINURCAT and the associated European Union Force Chad/CAR (EUFOR Chad/CAR) represent an interesting example of peacekeeping partnerships, their work was limited largely to protection of civilians and security sector training activities, without the ability to address underlying causes of conflict and instability. Regional dynamics and the Chadian government’s adept maneuvering hindered the intervention’s success in protecting vulnerable populations. Background Chad and its political fortunes have been deeply affected by regional actors since its days as a French colony. Since Chad’s independence in 1960, France, Sudan, and Libya have provided patronage, arms, support to rebel groups, and peacekeepers. Chad has hosted around 1,000 French troops in N’Djamena since the end of the colonial regime, maintaining one of three permanent French African military bases in Chad’s capital city. French and Chadian leaders place a premium on their personal relationships with one another to this day. Chad was the first country to host a peacekeeping operation from the African Union’s precursor, the Organization of African Unity, in response to a civil war between the government of President Goukouni Oueddei and the Northern Armed Forces of former Vice President Hissène Habré. -

African Dialects

African Dialects • Adangme (Ghana ) • Afrikaans (Southern Africa ) • Akan: Asante (Ashanti) dialect (Ghana ) • Akan: Fante dialect (Ghana ) • Akan: Twi (Akwapem) dialect (Ghana ) • Amharic (Amarigna; Amarinya) (Ethiopia ) • Awing (Cameroon ) • Bakuba (Busoong, Kuba, Bushong) (Congo ) • Bambara (Mali; Senegal; Burkina ) • Bamoun (Cameroons ) • Bargu (Bariba) (Benin; Nigeria; Togo ) • Bassa (Gbasa) (Liberia ) • ici-Bemba (Wemba) (Congo; Zambia ) • Berba (Benin ) • Bihari: Mauritian Bhojpuri dialect - Latin Script (Mauritius ) • Bobo (Bwamou) (Burkina ) • Bulu (Boulou) (Cameroons ) • Chirpon-Lete-Anum (Cherepong; Guan) (Ghana ) • Ciokwe (Chokwe) (Angola; Congo ) • Creole, Indian Ocean: Mauritian dialect (Mauritius ) • Creole, Indian Ocean: Seychelles dialect (Kreol) (Seychelles ) • Dagbani (Dagbane; Dagomba) (Ghana; Togo ) • Diola (Jola) (Upper West Africa ) • Diola (Jola): Fogny (Jóola Fóoñi) dialect (The Gambia; Guinea; Senegal ) • Duala (Douala) (Cameroons ) • Dyula (Jula) (Burkina ) • Efik (Nigeria ) • Ekoi: Ejagham dialect (Cameroons; Nigeria ) • Ewe (Benin; Ghana; Togo ) • Ewe: Ge (Mina) dialect (Benin; Togo ) • Ewe: Watyi (Ouatchi, Waci) dialect (Benin; Togo ) • Ewondo (Cameroons ) • Fang (Equitorial Guinea ) • Fõ (Fon; Dahoméen) (Benin ) • Frafra (Ghana ) • Ful (Fula; Fulani; Fulfulde; Peul; Toucouleur) (West Africa ) • Ful: Torado dialect (Senegal ) • Gã: Accra dialect (Ghana; Togo ) • Gambai (Ngambai; Ngambaye) (Chad ) • olu-Ganda (Luganda) (Uganda ) • Gbaya (Baya) (Central African Republic; Cameroons; Congo ) • Gben (Ben) (Togo -

Central African Republic (C.A.R.) Appears to Have Been Settled Territory of Chad

Grids & Datums CENTRAL AFRI C AN REPUBLI C by Clifford J. Mugnier, C.P., C.M.S. “The Central African Republic (C.A.R.) appears to have been settled territory of Chad. Two years later the territory of Ubangi-Shari and from at least the 7th century on by overlapping empires, including the the military territory of Chad were merged into a single territory. The Kanem-Bornou, Ouaddai, Baguirmi, and Dafour groups based in Lake colony of Ubangi-Shari - Chad was formed in 1906 with Chad under Chad and the Upper Nile. Later, various sultanates claimed present- a regional commander at Fort-Lamy subordinate to Ubangi-Shari. The day C.A.R., using the entire Oubangui region as a slave reservoir, from commissioner general of French Congo was raised to the status of a which slaves were traded north across the Sahara and to West Africa governor generalship in 1908; and by a decree of January 15, 1910, for export by European traders. Population migration in the 18th and the name of French Equatorial Africa was given to a federation of the 19th centuries brought new migrants into the area, including the Zande, three colonies (Gabon, Middle Congo, and Ubangi-Shari - Chad), each Banda, and M’Baka-Mandjia. In 1875 the Egyptian sultan Rabah of which had its own lieutenant governor. In 1914 Chad was detached governed Upper-Oubangui, which included present-day C.A.R.” (U.S. from the colony of Ubangi-Shari and made a separate territory; full Department of State Background Notes, 2012). colonial status was conferred on Chad in 1920. -

Why Is the African Economic Community Important? Mr

House Committee on Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Africa, Global Health, Global Human Rights, and International Organizations Hearing on “Will there be an African Economic Community?” January 9, 2014 Amadou Sy, Senior Fellow, Africa Growth Initiative, the Brookings Institution Chairman Smith, Ranking Member Bass, and Members of the Subcommittee, I would like to take this opportunity to thank you for convening this important hearing to discuss Africa’s progress towards establishing an economic community. I appreciate the invitation to share my views on behalf of the Africa Growth Initiative at the Brookings Institution. The Africa Growth Initiative at the Brookings Institution delivers high-quality research on issues of economic growth and development from an African perspective to better inform policy research. I have recently joined AGI from the International Monetary Fund’s where I led or participated in a number of missions to Africa over the past 15 years. Why is the African Economic Community Important? Mr. Chairman, before we start answering the main question, “Will there be an Africa Economic Community?” it is important to look at the reasons why a regionally integrated Africa is beneficial to African nations as well as the United States. In spite of its remarkable economic performance over the past decade, Africa needs to grow faster in order to transform its economy and create the resources needed to reduce poverty. Over the past 10 years, sub-Saharan Africa’s real GDP grew by 5.6 percent per year, a much faster rate than the world economy, which grew by 3.2 percent. At this rate of 5.6 percent, the region should double the size of its economy in about 13 years. -

Toward Resolving Chad's Interlocking Conflicts

Toward Resolving Chad’s Interlocking Conflicts AUTHORS Sarah Bessell, Kelly Campbell December 2008 UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE 1200 17th Street NW, Suite 200 Washington, DC 20036-3011 www.usip.org SYNOPSIS This USIPeace Briefing, based on a recent event, explores the internal, regional, and international components of the crisis in Chad. OVERVIEW The fragility of the Chadian government, as well as the fragmentation among Chadian civil society, political parties, and rebel movements, poses significant challenges that Chadian civil society, regional governments, African institutions and the international community must address with a coordinated strategy. Although the situation in the country is often examined through the lens of the Darfur crisis, several internal factors drive the instability in Chad and its regional actions. Thus far, efforts to address the political, security and humanitarian problems in Chad have seemed piecemeal and uncoordinated. A consensus is building that a comprehensive strategy encompassing the national, regional and international dimensions of the crisis is needed to move toward peace and stability both within Chad and between Chad and its neighbors. In October 2008, USIP and the International Peace Institute, in collaboration with Caring for Kaela, sponsored a multi-stakeholder consultation to address the political instability in Chad and its regional implications. The attendees included representatives from the Chadian diaspora, ambassadors from countries in the region, U.N. and EU representatives and experts from the non-governmental community and academia. This report summarizes the consultation’s main themes and recommendations. The first section addresses the security, political and humanitarian situation in Chad; examines the August 13 Political Agreement between the Chadian government and opposition parties and suggests ideas for the way forward. -

Independence and Trade: the Speci C E Ects of French Colonialism

Independence and trade: the specic eects of French colonialism Emmanuelle Lavallée¤ Julie Lochardy June 2012z Very preliminary. Please do note cite. Abstract Empirical evidence suggests that colonial rule and subsequent indepen- dence inuence past and current trade of former colonies. Independence ef- fects could dier substantially across former empires if they are related to the end of dierent preferential trade arrangements. Thanks to an original dataset including new data on pre-independence bilateral trade, this paper explores the impact of independence on former colonies' trade (imports and exports) for dierent empires on the period 1948-2007. We show that independence reduces trade (imports and exports) with the former metropole and that this eect is mainly driven by former French colonies. We also nd that, after independence, trade of all former colonies increase with third countries. A close inspection of the eects over time highlights that independence eects are gradual but tend to be more rapid and more intense in the case of exports. These results oer indirect evidence for the long-lasting inuence of colonial trade policies. Author Keywords: Trade; Decolonization; French Empire. JEL classication codes: F10; F54. ¤Université Paris-Dauphine, LEDa, UMR DIAL. Email: [email protected]. yErudite, University of Paris-Est Créteil. Email: [email protected]. zWe would like to thank participants at the IRD-DIAL Seminar and participants at the Con- ference on International Economics (CIE) 2012 for useful comments and suggestions. 1 1 Introduction Several studies highlight the consequences of colonial rule on bilateral trade. Mitchener and Wei- denmier (2008) assess the contemporaneous eects of empire on trade over the period 1870-1913. -

RECORDS CODIFICATION MANUAL Prepared by the Office Of

RECORDS CODIFICATION MANUAL Prepared by The Office of Communications and Records Department of State (Adopted January 1, 1950—Revised January 1, 1955) I I CLASSES OF RECORDS Glass 0 Miscellaneous. I Class 1 Administration of the United States Government. Class 2 Protection of Interests (Persons and Property). I Class 3 International Conferences, Congresses, Meetings and Organizations. United Nations. Organization of American States. Multilateral Treaties. I Class 4 International Trade and Commerce. Trade Relations, Treaties, Agreements. Customs Administration. Class 5 International Informational and Educational Relations. Cultural I Affairs and Programs. Class 6 International Political Relations. Other International Relations. I Class 7 Internal Political and National Defense Affairs. Class 8 Internal Economic, Industrial and Social Affairs. 1 Class 9 Other Internal Affairs. Communications, Transportation, Science. - 0 - I Note: - Classes 0 thru 2 - Miscellaneous; Administrative. Classes 3 thru 6 - International relations; relations of one country with another, or of a group of countries with I other countries. Classes 7 thru 9 - Internal affairs; domestic problems, conditions, etc., and only rarely concerns more than one I country or area. ' \ \T^^E^ CLASS 0 MISCELLANEOUS 000 GENERAL. Unclassifiable correspondence. Crsnk letters. Begging letters. Popular comment. Public opinion polls. Matters not pertaining to business of the Department. Requests for interviews with officials of the Department. (Classify subjectively when possible). Requests for names and/or addresses of Foreign Service Officers and personnel. Requests for copies of treaties and other publications. (This number should never be used for communications from important persons, organizations, etc.). 006 Precedent Index. 010 Matters transmitted through facilities of the Department, .1 Telegrams, letters, documents. -

Splintered Warfare Alliances, Affiliations, and Agendas of Armed Factions and Politico- Military Groups in the Central African Republic

2. FPRC Nourredine Adam 3. MPC 1. RPRC Mahamat al-Khatim Zakaria Damane 4. MPC-Siriri 18. UPC Michel Djotodia Mahamat Abdel Karim Ali Darassa 5. MLCJ 17. FDPC Toumou Deya Gilbert Abdoulaye Miskine 6. Séléka Rénovée 16. RJ (splintered) Mohamed Moussa Dhaffane Bertrand Belanga 7. Muslim self- defense groups 15. RJ Armel Sayo 8. MRDP Séraphin Komeya 14. FCCPD John Tshibangu François Bozizé 9. Anti-Balaka local groups 13. LRA 10. Anti-Balaka Joseph Kony 12. 3R 11. Anti-Balaka Patrice-Edouard Abass Sidiki Maxime Mokom Ngaïssona Splintered warfare Alliances, affiliations, and agendas of armed factions and politico- military groups in the Central African Republic August 2017 By Nathalia Dukhan Edited by Jacinth Planer Abbreviations, full names, and top leaders of armed groups in the current conflict Group’s acronym Full name Main leaders 1 RPRC Rassemblement Patriotique pour le Renouveau de la Zakaria Damane Centrafrique 2 FPRC Front Populaire pour la Renaissance de la Centrafrique Nourredine Adam 3 MPC Mouvement Patriotique Centrafricain Mahamat al-Khatim 4 MPC-Siriri Mouvement Patriotique Centrafricain (Siriri = Peace) Mahamat Abdel Karim 5 MLCJ Mouvement des Libérateurs Centrafricains pour la Justice Toumou Deya Gilbert 6 Séleka Rénovée Séléka Rénovée Mohamed Moussa Dhaffane 7 Muslim self- Muslim self-defense groups - Bangui (multiple leaders) defense groups 8 MRDP Mouvement de Résistance pour la Défense de la Patrie Séraphin Komeya 9 Anti-Balaka local Anti-Balaka Local Groups (multiple leaders) groups 10 Anti-Balaka Coordination nationale -

Republic of the Congo

UNITED NATIONS CONSOLIDATED INTER-AGENCY APPEAL FOR THE REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO JANUARY – DECEMBER 2000 November 1999 UNITED NATIONS For additional copies, please contact: UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs Complex Emergency Response Branch (CER-B) Palais des Nations 8-14 Avenue de la Paix CH - 1211 Geneva, Switzerland Tel.: (41 22) 917.1972 Fax: (41 22) 917.0368 E-Mail: [email protected] This document is also available on http://www.reliefweb.int/ iii iv TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY…………………………………………………………………………………………. 1 Table 1: Total Funding Requirement – By Sector and Appealing 2 Agency…………...… CONTEXT………………………………………………………………………………………….. 3 Table 2: Effects of the Wars 1997 – 4 1999……..………………………………...………. 5 Table 3: ROC 810,000 Displaced and Returned Persons by Urgan or Rural Origin… POLITICS, ECONOMY AND SECURITY……………………………………………………………. 5 Analysis, Scenarios and Response…….………………………………………………….. 7 A COMMON HUMANITARIAN ACTION PLAN (CHAP) TWO SCENARIOS………………………… 7 SCENARIO I……………………………………………………………………………………. 8 Table 4: 810,000 Displaced and Returned Persons by Place of Origin and Present Location……………………………………………………………………...…… 9 SCENARIO II…………………………………………………………………………………… 9 LINKING RELIEF AND DEVELOPMENT……………………………………………………………. 11 MONITORING……………………………………………………………………………………… 11 STATEMENT OF HUMANITARIAN PRINCIPLES……………………………………………………. 13 SECTORS TO ADDRESS, AND OBJECTIVES, FOR JANUARY – DECEMBER 2000………………. 13 Table 5: Individual Project Activities by 15 Sector……………………………………………. Table 6: Individual Project Activities by Appealing